Blog

Häromdagen köpte jag i tidningskiosken som så ofta förr två tidskrifter - Art e dossier och I grande maestri. Arte e dossier är en överdådigt illustrearad konsttidskrift som kommer ut varje månad. Den innehåller senaste nytt från konstvärlden, olika utställningar lite varstans i världen, intressanta artiklar och en bilaga som tar upp verk av en speciell konstnär, såväl historiska som moderna sådana.

.jpg)

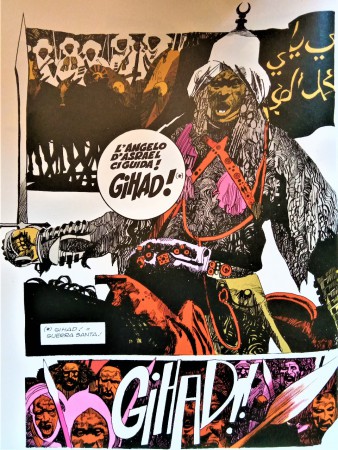

I grande maestri är en svit med olika serietidningar som varje månad presenterar välkända serietecknare, främst italienska och franska sådana. I såväl Frankrike som Italien finns ett stort intresse för sofistikerade, vältecknade serier. Varje månad kommer det ut en mängd sådana publikationer.

.jpg)

Tecknade serier, fumetti, brukar i Italien kallas la nona arte “den nionde konsten”. Jag antar att de andra då skulle vara musik, måleri, skulptur, poesi, dans, arkitektur, film och TV. Fast det får mig förståas att undra vad exempelvis mode och hantverk har tagit vägen. Nåväl den I grande maestri tidning som jag varje månad försöker få tag på innehåller serier tecknade och ofta skrivna av Sergio Toppi (1932 – 2012).

Denna månad handlade Art e dossiers bilaga om Félix Vallotton (1865 – 1925), som föddes i Lausanne men tillbringade så gott som hela sitt liv i Frankrike.

Månadens I grande maestri magasin med toppihistorier kallades Trame, kanske något i stil med ”områden/revir” och innehöll fem berättelser kring Nya Testamentet, en medeltida legend och en historisk skildring av den holländska kolonisationen av Indonesien under slutet av 1500-talet.

Uppenbarligen hade de båda tidskrifterna ingenting med varandra att göra, men de fick mig likväl att minnas förra sommaren då jag med mion hustru tillbringade en tid i Honfleur vid Normandies kust. Vi hade hamnat i en alldeles speciell gîte de passant, bed & breakfast. En artonhundratalsvilla som såg ut att ha varit skådeplatsen för någon historia av Flaubert eller Maupassant.

.jpg)

Även vårt rum tycktes hämtat från någon fransk artonhundratalsroman. Intrycket underströks av vår värds välförsedda bibiotek med franska klassiker och hans stillsamma pianospel – bachsviter och schubertsonater. En ytterst vänlig och tjänstvillig man, men mellan oss kallade vi honom för Norman, efter Norman Bates från skräckmotellet i Psycho, detta eftersom han var ungkarl, liknade Anthony Perkins och hade huset fyllt med uppstoppade djur. Men, det var långtifrån ett skräckhus – ljust och välstädat.

.jpg)

Varje morgon serverades vi en riklig och utsökt frukost, framställd enbart för oss i en fantasieggande salong med afrikanska masker, japanska lackskärmar. artonhundratalsporträtt, uppstoppade paradisfåglar och allsköns andra märkliga ting.

.jpg)

Bredvid salongen fanns ett sovrum med blodröda tygtapeter, överkast, förhängen och gardiner.

.jpg)

Alldeles intill sängen stod en stor, oformlig och uppstoppad penguin.

.jpg)

I den öppna spisen fanns ett svärdfiskhuvud placerat.

.jpg)

Det var denna mångfald av besynnerliga och exotiska ting som kom mig att tänka på Toppis serier. De handlar ofta om excentriska, äldre samlare av märkliga ting, som i serierna berättar sin historier.

Gamla stofiler instängda bland böcker och antikviteter, kanske inspirerade av Oesterhelds och Breccias argentinska seriemagasin Mort Cinder, som bland seriekännare nu räknas som en klassiker De handlar just om en spränglärd åldring som äger en antikvitetshandel i London och tillsammans med den odödlige Mort Cinder färdas från tidsperiod till tidsperiod. De förföljs ständigt av ett gäng sinstra ”blyögda” figurer som planerar att använda Mort Cinders hjärna för lugubra experiment.

.jpg)

Orsaken till att jag kom att associera Vallotton med Honfleur beror på att han ofta vistades i denna pittoreska hamnstad, som även har lockat till sig flera andra betydande konstnärer och fortfarande är fylld med konstgallerier. En av artonhundratalets betydande inspiratörer för andra konstnärer, Eugène Boudin, var för övrigt född i staden. Hans stora betydelse grundar sig på att han anses vara en av impressionisternas främsta föregångare och inspirationskälla. Stadens museum har fått sitt namn efter honom.

Ett annat museum inrymt i staden är Erik Saties bardomshem.Också han en av Honfleurs stora söner som för varje år tycks bli alltmer uppskattad som en av förra seklets stora förgångsmän, inte enbart inom musikens område utan också som ett betydande källsprång till den moderna konsten, speciellt i dess lekfulla och absurda framtoning . Då Satie var fyra år flyttade familjen till Paris, men då hans mor dog två år senare återvände han till Honfleur där han bodde hos sina morföräldrar tills han som tonåring återförenades med fadern i Paris.

Då jag bläddrade i magasinet med reproduktioner Vallottons konstverk kände jag igen en utsikt över Honfleur som motsvarade den man hade från en äng nedanför huset som vi bodde i. Fast på Vallottons tavla är den lilla staden dimhöljd, medan solen hela tiden sken då vi vistades där.

.jpg)

Valllottons landskapsskildringar är i allmänhet ljusa och soliga, speciellt de han målade i Honfleur och Normandie.

.jpg)

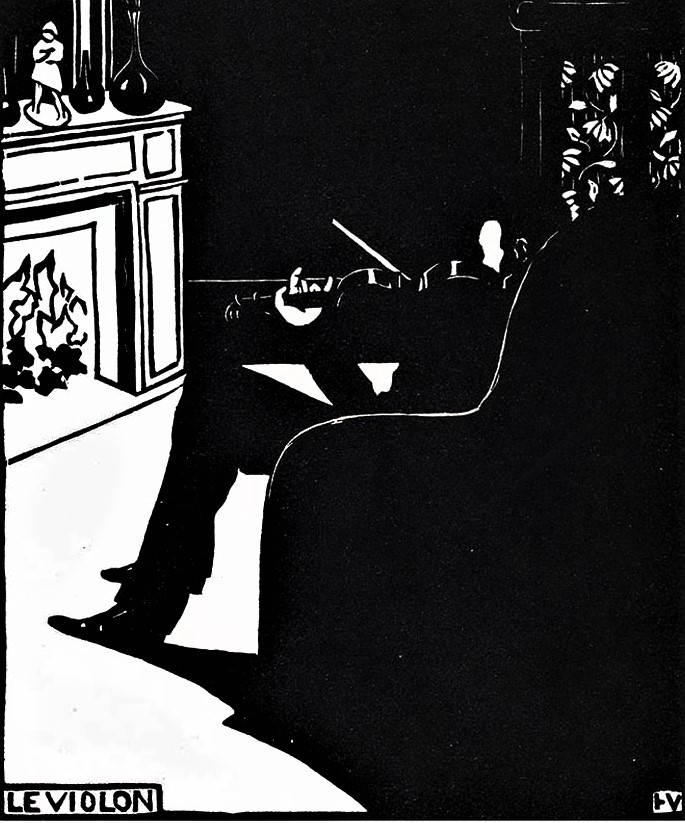

Hans mycket speciella grafik är dock i allmänhet mörk och spelar skickligt på skarpa kontraster mellan vitt och svart.

.jpg)

Emellanåt är hans träsnitt nästan helt svarta.

.jpg)

Många av konstverken utstrålar känslor av melankoli och ensamhet. Även då de framställer par, vilket de ofta gör, tycks de två aktörerna vara inneslutna i sig själva.

Vallottons grafiska stil är ytterst förenklad i meningen att han uttrycker sig med små medel, men det hindrar inte att han fyller dem med intensiva känslor. Som denna pianosejour där pianisten enbart är framställd medelst ett par streck, sittande iförd en ljus klänning mot en vit fond. Alltmedan de intensivt lyssnande herrarna sitter i mörker. Var och en i pose skild från de andra, men likväl vittnande om stor uppmärksamhet. De tycks samtliga vara gripna av musiken, fast var och en på sitt sätt.

På ett liknande sätt lyckas Vallotton i ett träsnitt han kallat ”patriotisk kuplett” - varje grafiskt blad är liksom hos Goya försett med en titel - med små, subtila medel framställa en mängd olika känslor hos en emotionellt engagerad publik.

Vallotton var en radikal man som arbetade för Le Cri de Paris, stadens ledande vänsterpublikation och La Revue Blanche, radikal även den, fast med en mer konstnärlig inriktning. Vallottons radikalism, som i det närmaste kan uppfattas som anrkistisk, yttrar sig emellanåt i hans dynamiskt originella framställningar av upplopp och demonstrationer, som alltid spelade med tomma, respektive fyllda ytor.

.jpg)

Vallotton drog sig inte för att fördöma våld och då speciellt brutalitet från myndigheternas sida.

Än mer skildrar han dock äktenskaplig intimitet, spänningen mellan man och kvinna. I en bild framställer han hur en man sitter i mörker i väntan på att en dam skall bli klar med sin aftontoalett. Som så ofta i hans andra träsnitt befinner sig kvinnan i ljus.

Bilden får mig att tänka på en sång av Charles Aznavour, Happy Anniversary:

Jag är klar sen mer än en timme, sitter här beredd,

har beställt champange och blommor, du är inte ens klädd

Det är absurt, du är så sur och irriterad,

jag säger inget när du är agiterad.

Känner väl ditt usla beteende

och sitter därför tyst; fånigt leende.

.jpg)

Musik, ensamhet, mörker och ljus är ofta närvarande hos Vallotton.

Dynamiska former, vitt och svart, tomma ytor som rytmiskt samverkar med helt ifyllda områden.

Efter att ha betraktat Vallottons träsnitt och sedan tagit fram Toppis serier upptäcker jag att denne ofta arbetar på ett liknande sätt som den franske mästaren. Som här, där Emiliano Zapatas väldiga sombrero enbart består av ett vitt fält.

En naken kvinnas former framträder vita mot en svart yta.

Kroppen på en soldat från Första Världskriget avtecknar sig som en vit, tom yta mot en svart bakgrund.

.jpg)

Liksom hos Vallotton står en ensam gestalt ofta isolerad från en grupp, i det här fallet en afrikansk ko som en vit bakgrund skiljer från hennes flock.

Den svarta skuggan på halsen av en skräckslagen tysk soldat blir scenen för ett nattligt överfall där angriparna framställs som vita silhuetter.

.jpeg)

Liksom hos Vallotton finns det mycket musik även hos Sergio Toppi, Det kan röra sig om en violinst från sjuttonhundratalet.

eller en saxofonist från USAs sydstater.

En utfattig bluesgittarist blir till representant för de udda, undertryckta befolkningsgrupper som Toppi ofta framställer och utfrån vars perspektiv han skildrar sina historier.

Det kan exempelvis röra sig om aborginiers konflikter med banditer i Australiens ödemarker.

.jpg)

Toppi finner ofta oanade och mindre kända områden för att skildra den sortens konflikter. Exempelvis vikingars möten och strider med Inuiter på det medeltida Grönland.

Eller Floridaseminolernas desperata kamp mot USAs armé mellan 1818 och 1858.

Toppi rör sig obehindrat över tidsåldrarna. Han följer mammutjägare under Stenåldern.

Sydtyrolska banditer under sextonhundratalet.

Tyska soldater under sjuårskriget, i scener som får mig att tänka på Stanley Kubricks Barry Lyndon.

Japanska samurajer.

Engelsmännens strider mot Il Mahdis trupper i Sudan.

Glömda gudar, uråldriga riter och bodhisattvor.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Amerikanska gangsters och korrumperade polismän.

Han för oss in i Vietnamkriget.

och långt in i en okänd framtid.

Som hos Vallotton kan Toppi plötsligt få våld att explodera.

.jpg)

Även det i form av oväntade möten mellan vitt skilda kulturer, som då han berättar om en naiv skotte som blir inblandad i en kandensisk konflikt under sjuttonhundratalet mellan fransmän, engelsmän och mohikaner.

Toppis serietidningsidor kan vara filmatiskt dynamiska, som i scener från en västernfilm av Sergio Leoni. Det kan röra sig om en anstormande noshörning.

eller en kosack som attackerar en engelsk äventyrare.

Emellanåt kontrasterar Toppi överlastad dramatik med lugna, i det närmaste tomma ytor, som här där demonen Iblis plötsligt uppenbarar sig för en ensam ökenvandrare.

Som så många andra serieskapare skyr inte Serio Toppi skräck och mystik och han omformar ofta mer eller mindre kända personligheter till skrämmande gestalter. Som Sobieskis polska ryttare under slaget om Wien 1683.

Eller en etiopisk prästs möte med en cynisk äventyrare.

Toppis seriesupplsag är även fyllda med vackra kvinnor, ofta framställda med en lätt ironisk vinkling, som denna åtråvärda kvinna som sensuellt breder ut sig i en av Titanics hytter, med förebilden Gustave Klimt diskret skymtande i bakgrunden.

Toppis kvinnor är ofta exotiska

och han fångar även skönheten hos äldre kvinnor.

Speciellt excellerar han i framställningen av mystiska kvinnogestalter i de talrika serier där han anspelar på berättelser ur Tusen och Natt, han använder sig då ofta av en mörkt glimmande färgsättning.

Trots att Sergio Toppi tycks ha en förkärlek för dynamiskt utformade, näst intill kaotisk öbverlastade bildytor kan han även utforma mer stillsamma bildförlopp, speciellt i de många serier han gjort med bibliska motiv, där han också använder mer färg än han vanligtvis brukar göra, men han gör det mer dämpat än i sina sagoinspirerade seriealbum .

Naturen är ofta närvarande i Toppis komplicerade kompositioner.

Hans naturskildringar är i allmänhet dynamiska, omväxlande och detaljerade. I vanlig ordning skapar han täta panoramiska mönster inom vilka han gärna integrerar olika djur.

Ofta låter han djuren tala och ibland även föra berättelseförloppet vidare.

Djuren kan vara offer, som sälarna i en serie om norska jägare i Arktis vid början av förra seklet,

eller då de dödas av ryska jägare under artonhundratalet.

.jpg)

Men det kan också röra sig om djur som berättar historier och då flyttar Toppi perspektiven till deras nivå. Som en varan från Komodo,

eller en gazell i Arabien.

En bälta som gått vilse i en sagovärld.

Toppi skildrar även kända levnadsöden och även då rör han sig över hela jorden och inom skilda tidsepoker. Det kan röra sig Shaka Zulu i södra Afrika,

Taras Bulba i Ukraina,

Djingis Khan,

.jpg)

Federico II av Svevia,

.jpg)

Custer och Sitting Bull,

.jpg)

.jpg)

och Baron von Richthofen.

Han blandar friskt. Exempelvis kan han låta en ondskefull gnom bli orsaken till tysk arrogans.

En engelsk äventyrare från artonhundratalet blir invecklad i strider med vikingar.

Toppi kan också ägna sig åt att hylla seriefigurer skapade av andra mästare, betydligt mer välkända än honom. Exempelvis Hugo Pratt och hans internationelle äventyrare Corto Maltese,

eller Tiziano Sclavis ”mardrömsdetektiv” Dylan Dog.

Toppi har sin styrka i bildernas förmåga att både berätta en historia och vara antopologiskt/historiskt korrekta. De historier han skildrar är i allmänhet inte lika minnesvärda, förvånande och effektiva som exempelvis Hugo Pratts historiska skrönor. Fast liksom Hugo Pratts hjälte Corto Maltese har Toppis karaktärer, då de inte är ondskefulla och snikna, en viss resning och utstrålar då en stoisk ensamhet, parad med världstrött cynism, oavsett från vilken kultur de än härstammar.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Och så finns där ju gubbarna som forskar bland gamla papper och prylar.

Eller som i en tid präglad av en ständigt stegrad tecknisk fulländning envisas med att plita med papper och penna.

Eller som sitter och drömmer om äventyr och fantasteri.

För en gångs skull har jag ställt samman ett blogginlägg med fler bilder än text. Kanske har min fascination inför Sergio Toppis bildvärld ryckt med mig och möjligen gett honom större uppskattning än vad andra kan tycka att han är värd. Vad vet jag? Hans i mitt tycke unika framställningar av en gränslös äventyrsvärld som rymmer all världens folkslag, dess djur och natur över ett väldigt tidsspann talar till det vetgiriga och äventyrslystna barnet som lever kvar inom mig.

Serietecknare har först under senare tid fått en del av den uppmärksamhet jag tycker de förtjänar. Sergio Toppi vars magasin numera är översatta till en mängd olika språk, verkade under hela sitt liv som tecknare i diverse barn- och ungdomsmagasin och fick inte någon större uppskattning inom konstkonnässörernas kretsar. Uppskattades och bedömdes han var det av den speciella skara som rörde sig inom seriemagasinens värld, men utanför den kretsen var han så gott som okänd.

Vi har en tendens att bedöma verk inom sina genreramar och många av oss missar kanske därmed stimulerande bekantskaper med världar som befinner sig utanför det som vi uppfattar som våra speciella intressesfärer. Jag känner kvinnor som enbart läser vad de kallar ”kvinnolitteratur”. Liksom flera som enbart läser deckare.

.jpg)

Vissa genrer har har så gott som uteslutande bedömts inom ramar begränsade av förutfattade meningar. Science fiction var uppenbarligen länge en sådan värld och det är möjligen fortfarande så att en tankeväckande författare som Liu Cixin, som nyligen ryckte med mig med sina sina visioner av kinesisk politik och parallella världar, helst läses av science fiction fans.

.jpg)

Likaså var det säkerligen med skräcklitteratur. Det tog lång tid för en mästare som Stephen King att bedömas utanför de speciella genreramarna och bli erkänd som den skicklige författare han faktiskt är (oftast - även han gör en och annan pinsam miss).

Så låt oss likt Sergio Toppi hylla mångfalden och förbehållslöst låta oss fascineras av den. Min fascination inför denne italienske serietecknares verk grundar sig säkerligen på min övertygelse om att fantasi, och chimärer verkligen existerar i form av en alternativ verklighet, att tro och magi är krafter som bör tas på allvar - det är även musik, målning, skulptur, poesi, dans, arkitektur, film och tv, samt teater, religion, mode och hantverk. Men sådant som är vackert, åtråvärt och tankeväckande måste njutas med omsorg och måtta, de är enligt mig den sanna estetikens förutsättningar.

Sigmund Freud wrote in 1929 a reflection on how an individual's wishes are counteracted by society's demands and expectations. Civilization and its Discontent begins with an obviously undeniable claim:

It is impossible to resist the impression that people commonly apply false standards, seeking power, success and wealth for themselves and admiring them in others, while underrating what is truly valuable in life. Yet in passing such a general judgement one is in danger of forgetting the rich variety of the human world and its mental life.

.jpg)

Thus Freud established our pursuit of perfection as one of humanity's greatest scourges. If we do not find perfection in ourselves, we seek it in others. Consequences for not accomplishing great expectations might be dire for ourselves, as well as for those unable to live up to the requirements we are imposing upon them. However, it may at the same time be argued that pursuit of perfection has been a crucial driving force behind the achievements of individuals, as well as the entire humankind. It made us humans, turned as into ”civilized” creatures. By striving for something better, a perfect existence, we have changed the prerequisites for our existence. We have transformed nature into culture. By doing so we made ourselves, as well as others, imagining us as being ”superior” compared to what we once were. However, no one is perfect. Human perfection does not exist. Coercion and rectifications are not requirements for improvement, rather the opposite.

.jpg)

We judge others in accordance with what we perceive as their state of perfection. We compare them to role models – those perfect creatures we, and especially others, should emulate. Children are tormented by parents who compare them to the offspring of other families. “Look at Yvonne she is already a medical doctor. What are you? Look at Gustav he has become a millionaire. What have you become? What have you done other than neglecting your natural gifts and qualifications? You are a good-for-nothing, a slugger, a failure.”

Comparisons make their appearance early on in a child's life and might in a defenseless creature create feelings of shortcomings and inadequacy. S/he might start to consider her/himself as a loser. Someone who is different from ”everyone else”. An insecure girl or boy might imagine that s/he is an alien. That s/he was left on the doorstep; an orphaned changeling, especially if her/his father and mother got into the habit of comparing her/him to ”more successful” siblings.

.jpg)

Our idols are those who have ”succeeded”, become famous and successful – the very criteria for an idol. They are the ones we want to be, or rather – whom we want our life companions, our children, our employees, our superiors, to be. During my time in the United States, I marveled at the large number of children's and ”young adult´s” books that had been written and published about successful, admirable youngsters, in whose spirit the growing-up generation should act.

Here in Italy, the Catholic Church is constantly publishing stories about young saints brought up by wise men and women. Like Dominic Savio, who died as a 14-year-old student of St. Giovanni Bosco (1815-1888), founder of the Salesian Order, which purpose it was to take care of abandoned, or poor children and raise them to become rural - or industrial workers. San Bosco wrote an inspirational book about Dominic Savio, in which he portrayed him as an ideal for students and young Christians. All over the Catholic world, there are statues of Saint Bosco and Saint Dominic.

.jpg)

China had (has?) its absurd cult of the young soldier and cultural hero Lei Feng: ”Follow Comrade Lei Feng's example.”

.jpg)

The Soviet Union had its Pavlik Mozorov, who betrayed his regime-critical father. After the Soviet authorities had executed his erring father, Pavlik was murdered by his rightly upset relatives. Thirteen-year-old Pavlik became hailed by a great variety of poems, biographies, a symphony, an opera, and several movies. Virtually every social system seems to be creating its own youthful heroes. Beautiful young people who are too good to be true.

.jpg)

It is not only saints, athletics, revolutionary heroes and young geniuses who serve as role models. We are also harassed by something as general and abstract as ”everyone else”, or so-called ”normal persons”. Idiotic generalizations, mirrored by expressions such as ”we, the people” and other all-encompassing expressions of mob madness, which constantly is roaring all around us. Comparisons with Tom, Dick, and Harry have been nailed into our thick skulls, or deeply rooted within our brains. We are whipped through life until we on our deathbeds are forced to admit: “Past! Past! Oh, had I but enjoyed myself while I could have done so! but now it is too late.”

.jpg)

As a child and youngster, I was an enthusiastic reader of Swedish translations of an American comic magazine series called Classics Illustrated. Unfortunately, my mother once threw away my collection of comics while she was clearing out our attic. There were Bang!, which featured exceptionally well-drawn comics translated from the French, as well as all my Donald Duck magazines. She probably thought I had put them up there because they no longer interested me. On the contrary, I treasured them all and wanted to keep them. The loss may not have been so great after all. If I now could revisit all those magazines I doubt I would be able to retrieve the magic that once devoured me.

.jpg)

Among all the Classics Illustrated, Faust was probably my greatest reading experience. I returned to it again and again. Faust was actually the last number of the original Classics Illustrated series issued by the American Albert Lewis Kanter. This specific Faust issue was unique in the sense that it contained both the first and second parts of the Tragedy. Faust´s second part is considerably more difficult to access than its first part and it took me a long time before I could read it in the original.

.jpg)

My grandfather had in his library a magnificent edition of Faust's first part, lavishly illustrated by a certain August von Kreling. I read it several times, but it was not until I read the second part in Britt G. Hallqvist's excellent Swedish translation and I finally got a grasp of the mighty work, which like other classics can be read several times and at every occasion be interpreted in a variety of ways. Goethe's Faust is occasionally heavy reading, though if digested with calm, patience and reflection it is quite thought-provoking.

Some years ago, I watched Aleksandr Sokurov's claustrophobic film Faust, which takes place in the early 19th century, within a small German, run-down town. I found some of it incomprehensible, though nonetheless, the movie became a near-hypnotically intense experience, with images etching themselves into my memory. A distorted, strange dream version that, in all its originality, provided an in-depth and unexpected angle to the Faustian story, which Sokurov. like in a Kafka story, limited within the boundaries of a small world, which suddenly opened up to unanticipated depths. Because of its strange allure Sokurov's version of Faust, Part I, although sometimes quite different from Goethe's story, is probably the interpretation, which in my opinion, comes closest to the great German author´s vision.

.jpg)

To me, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Faust – there are several other novels about the legendary or real Johann Georg Faust, who apparently lived between 1480 and 1540 – deals with the pursuit of perfection. The scientist/magician Faust pursues a single meaning/law governing our entire existence. In other words, he seeks God, the paragon for perfection.

The drama is launched in Heaven where Mephistopheles, who is either the Devil or a demon in his service, meets with God. However, before it all begins a Prelude takes place at a theatre where a performance is about to start. The salon is filling up, within a few minutes the curtain will rise. Grabbed by rampage fever, a Theatre Director, a Resident Poet and a Comic discuss what they expect from the show. The Director wants it to be a success, that the spectators will appreciate the spectacle and make others want to visit his theater so all performances will be sold out. The Poet does not really want to make a spectacle of his work. He has spent lonely days and nights labouring over his work. The Comic demands that the show will be entertaining, an unforgettable extravaganza.

.jpeg)

Through the Prelude Goethe makes it clear that his drama is a fairy tale. That the tragedy's characters are not ”real” people, they are not even based on any existing models, neither contemporary nor historical. They are mere figurines, perhaps even dolls (during Goethe's time it was common to present the Faust legend as a Punch and Judy Show). His characters are fictitious, symbols within a Morality Play.

.jpg)

Mephistopheles is a liar. He hides Truth behind a web of lies, obscuring the fact that we ought to use our knowledge to help others. Instead, Mephistopheles teaches us that happiness comes from satisfying selfish urges. He preaches a gospel based on a search for well-being and success at the expense of others. To quench our sexual desires without respecting the feelings of others To exercise power by suppressing our fellow beings, to revel in the misfortune of the destitute and underdogs. He tells us that in our constant search for well-being and money, the use of cunning and fraud is quite OK.

It appears that Oscar Wilde in his The Picture of Dorian Gray introduced a Mephistophelean figure. in the shape of Lord Henry Wotton. An elegant gentleman who exposes ”wrong, fascinating, poisonous, delightful theories.” A charming conversator, a spiritual companion endowed with wit and a brilliant intellect. No wonder that the handsome, but naive, Dorian Gray is enchanted by Lord Wotton's dazzling arguments and soon puts his radical theories into practice, unaware of the fact that the decadent and bored Lord Wotton used them only to shock his surroundings and appear as an interesting fellow. Lord Wotton questions every established truth and tries to replace it with his own sybaritic pleasure doctrine:

”Life is not governed by will or intention. Life is a question of nerves, and fibres, and slowly built-up cells in which thought hides itself and passion has its dreams. You may fancy yourself safe, and think yourself strong. But a chance tone of colour in a room or a morning sky, a particular perfume that you had once loved and that brings sublte memories with it, a line from a piece of music that you had ceased to play – I tell you Dorian, that it is on things like these that our lives depend.”

.png)

It is only when Dorian Gray despairs about himself and the kind of existence he has become trapped within that he realizes that Lord Wotton's teachings were false and corrupting. His affirmation that temptations are beneficial became the reason why Dorian Gray sought satisfaction at the expense of other human beings, thereby destroying both his own life and that of others. Oscar Wilde appears to have been a believer in art and aesthetics, assuming that they had no other purpose than to provide pleasure, forgetfulness, and relief. As an escape from the grotesque reality Dorian Gray indulged himself in egocentric exuberance, Wilde made him seek relief in aesthetics, a deliverance from threatening anguish – elegant home décor, exquisite perfumes, beautiful clothes, fine art, good literature, beautiful music. However, a polished surface of taste and wonder lured an increasing disintegration that soon affected Dorian's mind. More or less unconsciously he is eaten up by bad conscience. Dorian Gray had imagined that an unrestrained existence was the same as complete freedom:

The only way to get rid of a temptation is to yield to it. Resist it, and your soul grows sick with longing for the things it has forbidden to itself, with desire for what its monstrous laws have made monstrous and unlawful.

But by deceiving others, Dorian deceived himself and the final consequence of his recklessness was a complete moral and physical downfall. Dorian Gray ended up despised and hated by himself and all those he had known and corrupted.

.jpeg)

Oscar Wilde had not read Søren Kierkegaard's books, neither Stages on Life´s Way, nor Either/Or, in which the Danish philosopher analyzed the nature of the Aesthetic Man. A person imprisoned by a string of beads composed of enjoyable episodes. In fear of being deprived of his pleasures The Aesthetic Man focuses on specific moments that provide contentment and gratification, thereby his personality becomes fragmented. The Aesthetic Man loses itself, crackles. He becomes an actor, moving from set to set, from character to character. A liar who does not give himself time to reflect on his actions.

The Aesthetic Man fears and avoids moral obligations, chooses not to take any stand, neither to help others nor to assert his belief in an ideology. By following such a path The Aesthetic Man soon finds himself in a paralyzing state where only two choices remain – to take his own life or reconsider his attitude towards life. Unlike The Aesthetic Man, The Ethical Man accepts responsibility for his actions. For Kierkegaard, who in his own manner was a convinced Christian, morality meant relying on God – an unimaginable being, free from all human inhibitions and limitations created by time and space, eternal and infinite. An absurdity that our narrow intellect cannot comprehend. Thus, religion is entirely about faith and thus quite different from science. Faith is a personal experience, inexplicable and far removed from any scientific knowledge.

.jpg)

The truth that Mephistopheles preaches in Goethe's Faust is to live in accordance to a lie, a false illusion, similar to Lord Wotton's pleasure gospel. Mephistopheles' name probably comes from the Hebrew and the character was created in an effort to try to explain why it is so easy to lure even a good man from the path of righteousness. Each of us runs the risk of being tempted by our sensual desires. It thus becomes quite easy to imagine that besides God and his angels there exists a powerful and evil force – a Tempter. It was assumed that we are surrounded by demons, maybe a whole army of them, a legion of satanic devils. The leader of one of these wicked hordes became Mephistopheles, whose name consisted of the words מֵפִיץ (mêp̄îṣ) spreader and ט֫פֶל שֶׁ֫קֶר (tōp̄el šeqer) lie mason.

Like several other liars, Mephistopheles uses cynical charm. He is funny, all-knowing, and witty, just as a skilled manipulator should be. Mephisto is also a good and entertaining companion, as well as a good judge of human nature, well acquainted with diverse environments through which he moves like fish in the water. Of course, Mephistopheles does present himself to God as his loyal and submissive servant, yet his view of the world and human nature is light-years apart from the all-encompassing wisdom of the Ruler of the Universe.

.jpg)

Mephistopheles is incapable of comprehending the limitations of his ideology. He suffers from tunnel vision. A restriction that makes him perceive humans as governed by their basic instincts. According to Mephisto, human beings´ sole function is to satisfy their needs. Surrender to her/his insistent desires and ignore the well-being of others have to be the primary endeavor of any human being. Our Life-Lie.

The Egocentric is for Mephistopheles the essential idol of everything human. The Perfect Man whose every need has been met. The word idol comes from the Greek εἴδωλον, eidōlon, image, actually something that has no real existence. An interpretation of reality, a fantasy. An idol is a superhuman, a creature superior to all others. A Super Lie, a creation by The Master of All Lies – Mephistopheles.

The Superhuman perceives himself as free and independent. He needs no Master, no God. By believing that God is dead, the independent Superman imagines that he has been able to rid himself of human shortcomings, in particular of crippling compassion. However, Superman does not realize that the death of God means the Devil's victory. With God out of the game, Mephistopheles, The Master of All Lies and ultimate supporter of selfishness, will be sole Ruler the World.

.jpg)

Like many other full-fledged egocentrics, Mephistopheles is a gambler. Someone who believes that material gain brings happiness and success. Mephisto is incapable to refrain from making a hopeless bet with God, assuming that if he becomes victorious in such a desperate and relentless gamble, he will eventually gain world domination. The biased and limited Mephisto foolishly wants to convince God that He is wrong and thus make Him lose their constant struggle over human souls. However, Mephistopheles is actually a pathetic amateur compared to a master player like God, who has all the cards at hand and knows how to keep his trump card hidden until the game's final and decisive moment.

.jpg)

God is quite familiar with Faust, how he studies and struggles to reach the inner truth of life's meaning. Nevertheless, to arrive at any valid insight Faust has to leave his ivory tower and become exposed to the temptations inherent in human existence It is only after vanquishing earthly desires and thus prove that he cares for the wellbeing of others that Faust will become a true sage.

Without even realizing it, Mephistopheles acts as God's servant. By giving Faust access to earthly pleasures, bringing him deep down into the abode of desire, Mephistopheles assumes that by indulging Faust with sinful acts he will eventually gain control over Faust´s soul. However, God knows that Faust´s ability to learn from his mistakes will strengthen him, increase his knowledge and that Mephistopheles consequently will lose the bet. Faust will eventually be saved from Hell, but first, he has to be tempted by pleasures and earthly rewards. It is only after realizing into what abysses of despair selfish desire is able to push any human being, that Faust might mature and become a truly wise man:

What if he serves me in confusion now?

Soon I shall lead him into clarity.

A gardener knows the leafling nursling tree

With bloom and fruit will grace the years that follow.

The thrill of the drama, combined with the imagination and ingenuity Goethe spiced it with, rests in the reader's/spectator's doubts if Faust will nip at the baited hooks the wily Mephistopheles are dangling before him. However, Faust manages to wriggle himself out of the traps. Time after time Faust's undeviating curiosity saves him. His unquenchable thirst for knowledge – especially his dissatisfaction and struggle to improve everything – whips him onward. Faust does not become the full-fledged egoist Mephistopheles wants him to turn into.

.jpg)

Despite his good intentions, Faust does a lot of damage to others, mainly by never being fully satisfied. He constantly finds something to complain about. By the beginning of the play, Mephistopheles shows up at Faust´s place, at the very moment Faust is utterly disappointed with himself and his useless aspirations and thus plans to kill himself:

Alas, I´ve studied Philosophy,

The Law and Physics also,

More´s the pity, Divinity

With ardent effort, through and through

And here I am, about as wise

Today, poor fool, as I ever was.

My title is Master, Doctor even

And up the hill and down again

Nearly ten years wherever I please

I´ve led my pupils by the nose –

And see what we can know is: naught.

Faust looks around. He is enclosed by a book-packed study chamber, complete with useless alchemical devices, herbaria, stuffed animals and fetuses within glass jars; cramped, dusty and musty. Here he ended up, coming no further. As Jim Morrison sang:

This is the end, beautiful friend

This is the end, my only friend.

The end.

Faust has read and studied life but has not experienced it – the violence, the love, the pain, and the joy. In a despairing search for meaning, Faust has blindly pushed ahead into nothingness. Finally, he turned to magic, to superstition, dreams, and speculations. And then ... suddenly the gates of Hell are opened wide and the powers of darkness are summoned. Mephistopheles who, in the shape of a poodle, has followed Faust into his suffocating chamber, reveals his true self to the suicidal researcher and presents him with an offer he cannot refuse – he will turn the aged, dandruffed, whining Faust into an strapping young fellow and together they will explore the world, attract desirable women, gather experience and riches. They will wallow in happiness and beauty. Their agreement stipulates that Mephistopheles will be forced to fulfill any wish expressed by Faust. This while Faust only needs to accept one, single condition – if he someday becomes entirely satisfied with what Mephistopheles has provided for him and asks for a single moment to be extended – Verveile doch, du bist so schön, ”Stay a while, you are so beautiful”, then he will be condemned and forever belong to the Devil.

.jpg)

After a long life during which Faust, like each and every one of us, has made quite a number of mistakes, wounded and injured his fellow human beings, he finally finds himself in a situation where, as an administrator over a region, he has been given the opportunity to improve the lives of his subjects, especially by pushing back the sea with dikes, make ditches and turn the earth into cultivable fields. A struggle against nature for the benefit of man – culture against nature. However, like a ruthless dictator Faust intends to achieve progress with whip and carrot:

Get me workmen,

Thousands by any means, with cash

And whores and drink and with the lash

Encourage,tempt, pressgang them in.

I want news every day how far

Along with digging at that trench you are.

However, he perceives the wellbeing of others as his ultimate goal, stating that he will not rest until he has achieved it:

Stand on a free ground with a people who are free

Then to the moment I´d be allowed to say

Bide here, you are so beautiful!

Aeons will pass but the marks made by my stay

On the earth will be indelible.

I enjoy the highest moment now in this

My forefeeling of such happiness.

Finally, Faust has uttered the fatal words Verveile doch, Du bist so schön, ”Stay a while, you are so beautiful.” Mephistopheles triumphs and is about to drag Faust with him down to his kingdom of eternal suffering. However, Mephistopheles has actually lost the bet he made with God. The Devil is only familiar with sensual pleasures and desires; his powers and kingdom are based solely on selfishness and false self-realization. The Devil is utterly unable to understand that most of us might find joy in the well-being of others, just as Faust seems to assume by end of the play.

Faust är döende och det är uppenbarligen först nu i dödsögonblicket som han insett det som William Shakespears samtida, prästen John Donne skrev om i en av sina många begravningsdikter:

Ingen människa är en ö, hel och fullständig i sig själv

varje människa är ett stycke av fastlandet, en del av det hela

Om en jordklump sköljs bort av havet, blir Europa i samma mån mindre,

liksom en udde i havet också skulle bli,

liksom dina eller dina vänners ägor;

varje människas död förminskar mig,

ty jag är en del av mänskligheten.

Sänd därför aldrig bud för att få veta för vem

klockan klämtar; den klämtar för dig.

In Goethe´s Faust, Mephistopheles is revealed as a servant of God. His gambling with God was nothing more than God testing Faust's reliability. God seems to believe that Ein guter Mensch in seinem dunklen Drange ist sich des rechten Weges wohl bewußt, ”A good man does, despite his dark urges, know the right path.” In Faust, Goethe wanted to demonstrate that humanity's foremost driving force is its search for love. To a certain extent, Goethe does in his tale about Faust provide us with an answer to why we should care about other people's well-being. We are naturally social beings. We live in communities and such a life becomes more pleasant, more stimulating and safer if we behave in a caring and friendly manner, instead of being easily irritated and hostile.

However, to turn the messy, whimsical, weird, ironic, hard-to-interpret and occasionally skilfully written Faust into an uplifting tale about humanity's highest ideals would be to push beyond the goal. Faust is hardly a morally unassailable individual. He is far from being a saint. Faust is an egoist whipped through life by his urges and not the least by his lust. Since Faust is a male creature, he seeks love in women. Das Ewig-Weibliche zieht uns hinan, ”The eternal woman hithers us on.”

This conviction may be likened to Dante's love for Beatrice, which guided him through Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. It was divine love Dante sought through his Beatrice. She was an ideal, not a ”real” person, a Dream Woman. Dante was never allowed to live with her and when he wrote his powerful epic Beatrice was since long dead. It was absolute love Dante was chasing after in his dream, his Divine Comedy. During his search for knowledge, the Comedy's Dante is inexorably curious, constantly inquiring and in the end he finds l´amore che move il sole e l´altre stelle, ”the Love that moves the sun and the other stars.”

However, what Faust seeks in his love for women is far from being just heavenly bliss. Throughout Goethe's entire work and life, erotic lust is combined with scientific curiosity and this is also the case of his Faust. Love and sexual desire permeate the entire Faust; passionate desire – comic, tender, obscene, ecstatic, mysterious, grotesque. Even the disciplined and deeply religious Dante was possessed by love in its various shapes, though in his epic it was a search for chivalrous and religiously motivated love that urge him on – Divine Love. Nevertheless, just like Goethe, Dante also searched for absolute knowledge. The Comedy's Dante is inexorably curious, inquiring and seeking.

.jpg)

In Faust, angels come down from Paradise to bring with them Faust's redeemed soul, singing Wer immer strebend sich bemüht, den können wir erlösen,"The striver, the endeavourer, him we are able to redeem.” They emerge by the end of a multi-faceted work that was not at all like Dante's Comedy – a religious fable, but rather a tribute to human imagination, scientific research, a perpetual search for the truth. Goethe was not very religious, what he found in religion was love, but not a purely idealistic one, akin to the on Dante was seeking, but love in all its aspects, not least the erotic.

To some extent, Goethe did in his Faust saga provide us with an answer to why we should care for one another. We are naturally social beings. We live in communities and such a life, both within our family fand a larger community, is certainly more pleasant, more stimulating and safer if we are caring and friendly, rather than being easily irritated and hostile. We must affirm love, but not only as an exclusively sexual drive.

.jpg)

Goethe was just as arrogant as Dante, well aware of his vast expertise in a wide variety of areas. He considered himself more of a great scientist than a writer. Goethe's art was according to himself just part of a scientific search for the origin and meaning of life. How could all this knowledge be managed and used for the benefit of himself and others? In a letter, Goethe explained: In mir reinigt sich’s unendlich, und doch gestehe ich gerne, Gott und Satan, Höll und Himmel ist in mir Einem, ”Inside me a constant process of purification is going on and after all, I willingly admit that within myself God and Satan, Hell and Heaven are mixed together.” Faust is an argument about which part of the human nature that should be allowed to take the upper hand – the pursuit of evil, or pursuit of good.

Mephistopheles declares Ich verachte nur Vernunft und Wissenschaft, des Menschen allerhöchste Kraft, ”I only despise reason and knowledge, man's foremost strength.” The Devil´s driving force is his effort to corrupt science, knowledge, and love. Make them all serve a selfish end. Most scientists and teachers supported both National Socialism and Fascism. When we are deprived of compassionate intelligence, respect of and care for nature and people, we become bereaved of a shield and weapon that could be used for love and respect. Neglecting such moral strength makes as slaves under the same destructive force that Mephistopheles adheres to – The Master of all Lies and Sin. Man's search for love and goodness is by this demon reduced to an urge for wanton survival. Er nennt’s Vernunft und braucht’s allein, nur tierischer als jedes Tier zu sein, ”he [the humans] calls it Reason, but it only makes him more animal than an animal”.

.jpg)

Was it a pursuit of knowledge and love that brought me to Lund University? Maybe, anyway when I got there it felt like freedom.

Here we are now, entertain us.

I feel stupid and contagious,

here we are now, entertain us.

The feeling was probably not entirely different from Faust´s excitement after Mephistopheles had transformed him from being a tired, old man into a handsome youngster. After leaving the warm embrace of my family and the boring, limiting childhood town behind me, I was free to take care of myself in Lund. Like Faust, I threw myself into studies of those subjects things I liked – literature, art and religion, and not the least Drama, Theater, and Film, that at the time was an academic discipline. I experienced some bewildering romances and participated in life and fun, not the east nightly binges with like-minded friends, and an occasional excursion to cities more open and exciting than Lund, such as Copenhagen and Berlin.

Of course, there was some annoyance present as well. Lund had its fair share of boring know-alls who impressed their surroundings with prestigious knowledge. It was in the early seventies and chic to be radical; Mao, Lenin, Che Guevara, and Marx were hailed as heroes. ”Radical intellectuals” urged for world revolution, international solidarity and the importance of organizing to fight The State and Capitalism, while death to the family and religion was peached as well. While spreading around quotes by Mao, Marx, and Hegel, self-proclaimed ”radicals” became extremely annoyed if someone questioned their mediocre axioms. They praised one-party states with oppressive bureaucracies and called their brainwashing ideologies ”constructively implemented socialism”. If I did not agree with such luminaries they condemned, despised or ignored me, labeling me as a "right-wing reactionary" while drowning me with gibberish and ironic comments. The general narrowmindedness got on my nerves and it didn't help that I tried to get my opinions better organized by reading Mao, Hegel, and Marx. I did not understand much of their writings. The first two I found to be hard reading and rather hopeless cases, although parts of what Marx had written I found to be both thoughtful and well-formulated, although I could hardly get a good grasp of his extensive writings.+

.jpg)

However, I counted upon the good companionship of witty friends from my hometown. Claes, Stefan, and Didrik were moderately politically interested. With them, I could discuss other essentials. When it came to politics and philosophy, my corridor mate (the usual living quarters of students were single rooms along a corridor with a common kitchen) Mats Olin became a solid rock and reference point. He did like me come from the rural district of Göinge, but unlike me, he had solid language skills; read unhampered English, German and French, and even Spanish. Mats was knowledgeable about politics, philosophy and social anthropology, and he also read a great deal of fiction far beyond what was considered to be mandatory reading for left-wing sectarians.

It was through Mats I discovered alternatives to the obviously omnipotent, uniform, and often violent totalitarianism that swirled around me. He made me aware of The Frankfurt School, of Marcuse, Illich, Castoriades, Baudrillard, Feyerabend and a host of other new thinkers and critics of biased, totalitarian ways of thinking. Through Mats a whole new world opened up to me, fueled by my increased interest in mysticism and ”alien” cultures. Mats became the reason to why I became interested in the Situationists and during one of our trips to Copenhagen I bought a couple of Danish translations of essential Situationist literature, among them Guy Debord's Society of the Spectacle and an anthology compiled by Victor Martin, one of the leading Danish Situationist artists – There is a Life after Birth.

.jpg)

In Lund, I met a Situationist with whom I became briefly acquainted. Sometimes I encountered the Jean Sellem at the pub Spisen, The Fireplace, where he often nested at a corner table together with the notorious, eternal student Maxwell Overton. Jean Sellem always drank tea, while Maxwell drank cheap Turkish wine, Beyaz, it was bad enough as it was and became even worse due to Maxwell´s habit of putting sugar lumps in his wine glass.

Sellem was happy to talk and always in a contagiously good mood. Probably a dozen years older than I was I found him to be an unusually stimulating acquaintance – witty and with astonishing insights, as well as a lighthearted, unpredictable humour emphasized by a, to my ears at least, peculiar and very strong French accent, his bottle-thick glasses, unvarnished, as well as his unkempt. wildly frizzled hair. A true bohemian artist and a healthy element among all the boring ”leftist intellectuals”, many of whom did not at all appreciate the anarchistic Sellem whose Gallery Saint Peter for Experimental and Marginal Art was opposite Lund´s Book Café, an ”independent and unsectarian left-wing bookstore specializing in society-oriented, radical and Marxist literature”.

.jpg)

Jean Sellem, who made his appearance in Lund sometime in the late sixties, had been affiliated with The Situationist International (SI), though this ”fellowship” had been disbanded in 1972. Already before that, several of its members had been excluded after being skeptically inclined towards the increasingly dogmatic, left-revolutionary direction in which the association was moving. When I met him, Jean Sellem seemed to be more attracted by the Fluxus movement, which also was some kind of artistic fellowship, but far more extensive, and cross-culturally inclined than the Situationist International. Fluxus had no formal membership, though many of the most respected artists at the time were considered to be Fluxus affiliated; for example, John Cage, Joseph Buys, Nam June Paik, Terry Reily, Öyvind Fahlström, Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneeman and Wolf Vostel. Like Sellem, they devoted themselves to conceptual art, but he had distanced himself from the celebrity image that flourished within Fluxus circles and was more attracted by a group that identified itself as SI 2, or Situationist Bauhaus, headed by Asger Jorn's brother Jørgen Nash. This so-called the Second Situationist International was more focused on art than The First Situationist International and found its center in the artistic collective Drakabygget just outside Örkelljunga in northern Skåne, my home district.

.jpg)

Sellem considered it to be fascinating that my father knew Jørgen Nash, something he confirmed when they met and Nash stated that he counted upon Axel Lundius, from in the local newspaper Norra Skåne, Northern Skåne, as ”one of us”. Sometime after I got to know Jean Sellem, he was involved in a complicated battle with Lund Municipality, which had decided to withdraw its cultural contribution to his gallery. After he had invited me to read a few of my short stories, Gottegrisen, The Sweet Tooth, and Det blödande barnet, The Bleeding Child, in his gallery, Sellem obviously counted me as a supporter and furthermore published two of my drawings in one of his magazines. Sellem was a quite assiduous publicist and everything that happened in his gallery was carefully documented and archived in his Archive for Experimental and Marginal Art.

One day when I entered his gallery, Jean Sellem came running towards me and shouted in his inimitable French-Swedish:

- Ah, Lundius! Come in, come in! Close the door quickly so the rabbit does not run away!

I did as he said and somewhat confused looked around the place. There was no rabbit in sight. The floor of the gallery's exhibition hall was covered with newspaper strips and in the middle of them was a large salad head that Sellem every morning bought at the Saluhallen, the town market. There was, however, no rabbit. The installation was part of an exhibition containing an ”imaginary” rabbit.

.jpg)

Sellem was, as always when I met him, in a brilliant mood and our conversation was occasionally interrupted by his chuckling laugh. He told me of an initiative, an art action, he was staging together with a new-found friend of his, the graphic artist Andrzej Ploski, who recently had arrived from Kielce in Poland. Ploski had some problems with the Artists' National Association (KRO) and Sellem had difficulties with the municipality. On one of the gallery's display windows he had in large letters written: ”Censored by S [the Social Democrats] and M [the Moderates, a right-wing political party] in Lund.” Since Sellem was no longer receiving cultural support from the municipality, he now planned to print his own banknotes and sell them for ten Swedish crowns apiece, in support of his gallery.

.jpg)

The banknotes were to be designed by Ploski and issued by something they called The Lundada Bank and referred to as ren money, i.e. clean money. Ren is a word that can be interpreted as both ”clean” and ”reindeer” and the banknotes thus referred to the municipality's Social Democratic chairman, Birger Rehn. The bank's motto would be printed on the banknotes: Enighet ger stryk. Alla för alla, alla för ren, a play on words that is almost impossible to translate. A direct translation would by ”Unity results in a beating. One for all, all for Rehn”. In those days Swedish banknotes carried the caption Hinc robur et securitas, Latin for ”hence strength and security”. However, the Swedish word for ”strength” could also mean ”a beating”. ”One for all, all for one” was, of course, the motto for The Three Musketeers, which in Swedish becomes en för alla, alla för en, though Sellem changed ”one”, en, for ren, ”reindeer”, the name of the municipality´s chairman., Birger Rehn.

Sellem also worked on a book with sixteen full-page engravings by Andrzej Ploski. They were thinking of calling their book Lundius, Commedia dell´arte and Sellem now wondered if it was OK for me and my relatives if they used our family name. I explained that it certainly did not matter at all to my relatives, they would rather like it. When the book was published, Sellem gave me several copies of it, as well as a number of posters that my father sent to his brothers and my cousins. He framed his own copy and hung it in the entrance to my childhood home.

.jpg)

Through the books Mats Olin made me buy and my acquaintance with Jean Sellem, I became increasingly interested in the Situationists. Before he ended up in Lund, Sellem had drifted around in Europe, mostly making his living as a sidewalk artist. He had spent quite a long time in Germany where he had a daughter, Marie-Lou Sellem, who now is a fairly well-known actress, especially as she made a career in television where she has starred in several films and series. After his time in Germany, Sellem studied at an art school in Copenhagen. Sellem told me that some time afterward he had in Finland found that he could live on selling his own art, something that worried him and made him relinquish his own income-generating artistic creativity and in a truly Situationist spirit instead began dedicating his time to inspire and support other artists to create ”situations” which could awaken people to discern the ”real state of life”.

Jean Sellem came to Sweden and Lund, became fond of the small university town where he met and fell in love with Marie Sjöberg, who became his assistant, photographer, and all-arounder. Together they did between 1970 and 1982 administer Gallery Saint Peter. When I wondered what he was living on, Sellem explained that until now the Lund Municipality had willingly supported him and provided a yearly grant to his gallery, furthermore, he could count upon the support of his co-worker, Marie, who worked as a night nurse at Lund's hospital. When I asked him if his way of life was in accordance with the Situationist ideal, Sellem explained that this was how he interpreted it.

Until 1972, Guy Debord (1931-1994) had been the Situationists´ secretary, strategist, philosopher and disciplinarian, who regularly accepted or excluded members from an association he refused to call ”organization”. The movement, or whatever it could be called, was founded in 1957 under the name Situationist International (SI). Its ”ideology” was in 1960 established in a Manifesto, which introduction stated:

The existing framework cannot subdue the new human force that is increasing day by day alongside the irrisistible development of technology and the dissatisfaction of its possible uses in our senseless social life.

The Situationists had experienced the emergence of oppressive totalitarian states, World War II's devastating catastrophe culminating in the industrially efficient slaughter within extermination camps and the atomic bombs' effective eradication of human life. The War´s aftermath meant in several European countries abject misery, which however was soon followed by a rapidly improving economy, while nations experienced repression under direct Soviet rule or communist minion regimes. It was a time marked by doubts, worries, and protests, accompanied by alternative art in the form of free jazz, abstract expressionist painting and the dissolution of traditional storytelling techniques. The Situationist Manifesto stated that human slavery characterized by mind-numbing wage work only benefitted a few capitalists, supported by a commodity fetishism that has replaced ”real” life with an ever-increasing, frantic consumption of commodities, which quantity overshadowed and destroyed their quality. The Situationists wanted every person to become an artist in charge of her/his own life, rather than remaining as an alienated cog in a machinery that produced commodities that no one actually needed.

We must liberate our inherent creative power, let loose our playfulness. Turn life into a feast. Let our own imagination, render self-proclaimed ”experts” redundant, expose their true nature as simple lackeys in the service of ruthless capitalists. Instead of being entangled in the net of commercially conditioned manipulations, each and every one of us should be offered an opportunity to become an ”amateur expert”, members of a richer, more playful, more open society, instead of being demeaned and humiliated as a hapless consumers/producers.

There is a life after birth! Be realistic, demand the impossible! They buy your happiness, steal it back! Depression is counter-revolutionary! The boss needs you, you don't need him! Stalinism is a rotten corpse! Prohibit prohibition! The beach is under the asphalt!

.jpg)

A new openness could be manifested through the creation of ”situations”. A first step would be to free art from its misappropriation and exploitation by market forces, which by pricing it has transformed artistic expression into a commodity. An urgent action/situation would according to the Situationist Manifesto be to carry out a spectacular coup against an institution which for The Situationists was the epitome of oppressive State bureaucracy´s ongoing attempts to equalize and neutralise art, science, and education by transforming them into subservient slaves of a centralized, controlling society where everything has been provided with a monetary value. Where everything is up for sale.

A first step would be to occupy UNESCO, The United Nations Organization for Science, Education, and Culture, which has its headquarters in Paris. A huge, sumptuous building containing a select group of highly-paid “experts”, who decide what kind of “culture” may be deemed worthy of global support. A situation recommended by the Situationist Manifesto would be to use the UNESCO headquarters for the announcement of a proclamation that invited the people of the world to participate in the creation of a human existence, characterized by trust, love, and imagination.

.jpg)

Such a negative view of UNESCO and the commercial valuation of art seemed to be contradicted by a large painting by Asger Jorn, which I used to pass in one of UNESCO's large foyers when I ten years ago functioned as an insignificant cog within the Organization's vast machinery. The painting was purchased in 1958, the same year when UNESCO's stately headquarters were opened in Pars. The Danish artist Asger Jorn was a good friend of Guy Debord and one of the initiators of the Situationist International.

Asger Jorn was already making money on his art and through the years he became an important driving force behind and a significant financier of various Situationist activities. Asger Jorn (1914-1873), whose original name was Asger Oluf Jørgensen, was an amazingly energetic and multifaceted Jack of all Trades. Twenty-two years old, he had scraped together enough money to buy a motorcycle and use it for traveling to Paris to study art under the famous Vasily Kandinsky. However, Kandinsky turned out to be severely depressed, tired, old and poor. Instead, Jorn began studying for Fernand Léger and eventually became acquainted with the renowned, constructivist architect Le Courbusier. Together with Courbusier Asger Jorn worked on the decoration of the Temps Noveaux Pavilion, which was part of the 1937 legendary World Exhibition.

.jpg)

After admiring Le Courbusier, Jorn soon came to regard his ”misanthropic homes” as dreary and sterile places. Above all, he found the Functionalism that Le Courbusier advocated to be a force that hindered and circumscribed the all-encompassing experience and appreciation of life and imagination that true art should contribute to. A release of each individual's creativity. All people should be provided with opportunities to contribute to the growth and change of their local environment. Cities ought to become living organisms, not solidified in pre-established forms and systems, but dynamic and changeable in symbiosis with the people living and working within them. Jorn came to regard Le Courbusier's Plan Voisin from 1925, a proposal to rebuild large parts of the centre of Paris, as an absolute abomination, a perfect antithesis to his own urban thinking.

.jpg)

After returning to Denmark, Jorn immersed himself in studies of magic and ancient Nordic art. During the war, he joined the Danish resistance movement and contributed with several articles to Helhesten, a magazine paying hommage to folk art, Nordic paganism and uncontrolled spontaneity. Helhesten, The Horse of Hell, was a Danish supernatural creature, three-legged and pitch black it appeared on moonless nights in the vicinity of graveyards. Those who were unfortunate enough to encounter this lugubrious horse were sure to die shortly after the confrontation. By naming their magazine after a threatening apparition the artists who contributed to it wanted to suggest that their art was a deadly threat to the occupying Nazis. During the War, Jorn also translated Kafka into Danish and began to collect a large number of photographs that eventually became an archive he named 10,000 years of Nordic Folk Art.

.jpg)

After the War, Asger Jorn resumed his restless travels and made contact with artists around the world. His abstract paintings sold well and progressively he became quite well known. At Café Notre Dame in Paris, he did in 1948, together with the author Christan Dotremont and the artist Constant, a pseudonym for Constant Anton Nieuwenhuys, establish the artist group CoBrA. The name was constructed by the first letters of the artists´ hometowns; Copenhagen, Brussels, and Amsterdam. Shortly afterward, the Dutch artists Karel Appel and Guillaume Cornelis van Beverloo (Corneille) joined the group. They already shared an apartment with Constant. In their Manifesto, CoBrA declared that their spontaneous art was intended as a denial of the decadence of European art, which had begun during the Renaissance. They wanted to counteract all specialization and ”civilized art forms” and instead support a ”direct” primitive and childish art, based on a free and joyful collaboration between material, imagination, and technology. Their art would be equivalent to ”inhibition-free well-being”. CoBrA had a major impact, but the group only remained united for a few years. One of the reasons for its dissolution was that Asger Jorn began an intimate relationship with Constant's wife.

.jpg)

After CoBrA was disbanded in 1951, Asger Jorn returned to Denmark, depressed and severely ill with tuberculosis. However, in 1953 he managed to regain his health and stamina. Jorn had become interested in pottery and moved to the coastal city of Albissola Marina in Liguria, the seat of the legendary pottery company Giuseppe Mazzotti Manifattura Ceramiche founded in 1903 and became, after being recognized by Futurist leader Tommaso Marinetti, a production centre for futuristic fine arts and craftsmanship. Soon a number of artists gathered around Asger Jorn, among them Constant, who had forgiven his former friend´s elopement with his wife. Jorn was by now married to Constant's ex-wife, Matie van Domselaer, with whom he had two children.

Constant began working on an urbanization project he called The New Babylon and elaborated large architectural models through which he tried to create the dynamic urban landscapes he often discussed with Asger Jorn.

.jpg)

As usual, Asger Jorn within a short timespan established stimulating contacts with local artists. One of them was the chemist and multi-worker Giuseppe Pinot-Gallizio, who in Alba, a mile north of Albissola Marina, owned an industrial plant producing herbal sweets and remedies.

.jpg)

Pinot-Gallizio was a left-wing politician and put Constant in touch with the leaders of a Romani camp, where they together with the residents began to experiment with realizing their ideas of alternative urbanism, within which individual´s creative powers would contribute to the creation of a dynamic society. Constant was musically talented. He was a skilled violinist and guitarist and had early on become fascinated by gypsy music, which led him to learn various improvisation techniques from the Romani and to play the cimbalom (tsymbaly).

.jpg)

In his Alba factory, Pinot-Gallizo developed, in collaboration with his son and Asger Jorn, something he called Pittura industriale, Industrial Art Production. With the help of various machines and innovative techniques he did together with a local workforce create up to 70 metres long canvases, filled with spontaneously created art. These ”pieces of art” were then sold by the metre as fabric goods.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Later on, Pinot-Gallizio created within art galleries in Turin, Paris, and Amsterdam a kind of ”environments” – a ”raw” ambient art he called Cavernas dell´antimateria, Caves of Antimatter. Gallery visitors were invited to move within a maze of painted canvases where they were surprised by unexpected ”situations”.

Soon artists from the global art world became attracted by Albissola Marina, among them Asger Jorn's friends from Paris – Guy Debord and his wife Michèle Bernstein. They were among the leaders of a group called Lettrists, a movement that intended to trace the origins of human thinking and action. By breaking down the language into its smallest units; moaning, sighing, screaming and changing the alphabet into ”primordial” signs and symbols, they wanted to create building blocks for the build-up of new, more spontaneous, personal and free modes of expression.

.jpg)

Lettrism was created by like-minded young people in post-war Paris, within bars, cheap restaurants, and shabby hotels. In August 1945, twenty-year-old Isidore Goldstein arrived in Paris, after spending six weeks traveling through post-war Europe from his Romanian hometown Botşani. With him, Isidore Goldstein brought a wealth of poems and writings inspired by his idol and compatriot Tristan Tzara (Samuel Rosenstock), who in 1916 in Zurich, together with the German Hugo Ball, had founded the famed Dada movement.

Isidore intended to shock and offend everyone. Already a few months after his arrival in Paris he was thrown out of Theatre du Vieux-Colombier, where a play by Tzara was performed. Isidore had several times interrupted the performance by roaring: ”Dada is dead! Lettrism has taken its place”. Scandals quickly erupted around him. In 1949, Isidore had managed to get a novel published, Isou ou la mécanique des femmes, Isou, or the Mechanics of Women. This autobiographical novel was a tribute to sixteen-year-old and later concept artist Rhea Sue Sanders. The scandal was caused by the fact that Isidore Goldstein claimed that simultaneously with his mistress he had for four years made love to no less than 175 women and if time and space permitted it he could describe each act in great detail. Isisdore Goldstein was fined 2,000 francs, sentenced to eight months imprisonment and the court decided that all existing copies of the book should be immediately destroyed. However, after a month the prison sentence was suspended.

After two years in Paris, Isidore Isou, as Goldstein now called himself, had established himself as a significant culture personality and the prestigious publishing house Gallimard published two of his books: Introduction à une nouvelle poésie et à une nouvelle musique, Introduction to a New Poetry and a New Music and L'Agrégation d'un nom et d'un messie, The Merging of a Name and a Messiah.

After six years in Paris, Isou began to express himself through film. Traté de bave et d´éternité, Treaty of Mucus and Eternity, which was divided into three parts. The first, called The Principle, depicted how people moved along Parisian streets, accompanied by excerpts from a lecture on film. The second part, The Development, described a romantic meeting between a man and a woman and consisted entirely of clips from other films. The third ”chapter” was called The Evidence and was entirely composed of abstract imagery, including so-called leaders, i.e. sequences of numbers that were used starting strips for films. Not many first-time visitors succeeded in enduring the entire screening and left the theatre under loud protests. When the film was later presented during the Cannes Film Festival, the influential Jean Cocteu watched and appreciated Traté de bave et d´éternité, making sure it won first prize in a newly established film category – The Best Avant-garde Performance.

.jpg)

Isou's incomprehensible film was based on two Lettrist concepts, which later were further developed by the Situationists – détournement and dérive. The first concept could possibly be translated as ”return/bringing back” and meant that artists made use of images and expressions manufactured by the so-called Mass Society, which had been created by capitalism and the bourgeoisie. Artists destroyed, cut up, and manipulated all kinds of imagery in such a way that it came to transmit an ”alternative world view”. Asger Jorn explained the détournement process as a unique form of innovation: ”Only those who are capable of disparaging generally accepted opinions will be able to create new values.” Situationist artists used advertisements, comic books, porn magazines, B-movies, kitsch and trashy art. They cut them up, united the pieces, added new sentences and hints and then published the results in magazines, as posters, or movies.

Asger Jorn created new, critical artwork Peinture's modifiées, Modified paintings, meaning that he manipulated, changed and painted over cheap artwork he had bought in flea markets.

A possible translation of dérive might be ”drifting”. This meant that you wandered aimlessly within an urban landscape, without a set goal and any intense involvement. Maybe akin to the introduction to Christopher Isherwood´s Goodbye to Berlin: ”I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.” A ”therapeutic” approach aimed at clearing your brain from its constant struggle to organize and subordinate impressions within logical frameworks.

.jpg)

During her time as an art and design student, my oldest daughter became inspired by dérive, especially as it was expressed by English Psychogeographers. She used city maps to draw in random red lines, which during town itineraries had to be followed as closely as possible, regardless of the obstacles you might encounter. She also designed an Urbilabe, a kind of ”modified compass” manipulated through the introduction of various components, giving different directions. Her Urbilabe was intended to inspire ”its users to explore an urban landscape in a spontaneous and inspiring manner.”

.jpg)

A year after the premiere of Isou's first movie, his six-year-younger adept Guy Debord presented an even more incomprehensible film – Hurlements a faveur de Sade, Screams in Favour of de Sade. A movie entirely devoid of pictures. The flickering movie screen remained white during readings from a book Isou had written about film, as well as detached dialogues from John Ford's Rio Grande, recitations from James Joyce´s Finnegans Wake, as well as the Code civil des Français. During longer breaks between the readings, the screen remained completely black. It was also blackened during the last twenty minutes of this quite patience-demanding presentation.

While making the film, Debord was responsible for the Lettrist magazine Potlatch. The word means ”give away” and denoted major events during which indigenous people along the west coast of North America accompanied by dance and partying gave away large portions of their property.

.jpg)

The magazine Potlatch was issued on a monthly basis and distributed free of charge. Each number was initiated by the words:

All texts presented in Potlach can be freely reproduced, imitated and/or partially quoted without any reference whatsoever to the original source.

.jpg)

Soon there came a break between Isou and Debord. They were both complicated personalities and began to attack each other in various writings. Especially Isou had become utterly annoyed by Debord and his Situationist International, which he described as a neo-Nazi organization.

In the summer of 1957, Guy Debord, his wife Michèle Bernstein, as well as the English psychogeographer Ralph Romney visited Asger Jorn and his Italian counterparts within an artist community Jorn had established in Albissola Marina as part of something they called MIBI, or The International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus. Asger Jorn's good friend, the young philosophy student Piero Simondo, had an aunt who owned a small hotel in the village of Cosio d´Aroscia and it was there that the Situationist International (SI) was established amidst extensive wine-drinking and violent discussions.

.jpg)

During the twelve and a half years of the organization´s existence, it had at most seventy-four members (63 men and 11 women). Despite its limited membership SI came to have a major impact and inspired a wide variety of artists, writers, and philosophers. Guy Debord, who delved deeper into philosophy and politics, believed that SI's ultimate goal could not be to create experimental and engaging artworks/situations without producing a truly revolutionary consciousness. Capitalist society, and to the same or even higher degree, state capitalist systems like those of the Soviet Union and China, had vanquished all attempts to challenge the hegemony of commercialism and bureaucracy. The bourgeois class had appropriated avant-garde culture, put a price tag on all art and thus turned it into a commodity. Debord's conclusion was to exclude all artists from the group, something that did not prevent him from continuing to receive financial support from a successful artist like Asger Jorn.

Even if the Situationists were critical of prevailing political and social systems and advocated an ”entirely new” view of life and culture, they were nevertheless children of their time. In the United States, we find The Beat Generation and Great Britain had its Angry Young Men, just to mention two of all those ”alternative movements” that had sprung up all over the world. Several of these movements criticized the current, dominant society, though, at least initially, most of them had been generally ”aesthetically” inclined. However, most of the members of the governing segment of society were deeplý worried by the wars in Algeria and Vietnam, as well as other ”resistance movements” in the Third World. Some intellectuals approved of what they considered to be the creation of ”social alternatives” in ”socialist” societies, like those established in Cuba or China. They immersed themselves in Marx and Hegel while integrating their reading and thinking in writings and actions.

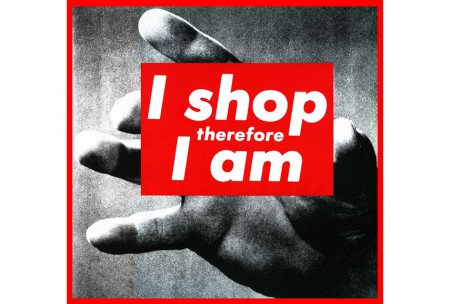

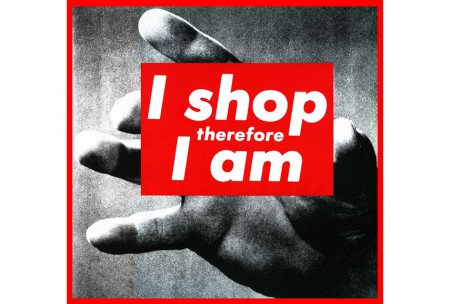

Debord stated that the current Capitalism, as well as Communist totalitarian systems, were manifestations of what he called The Society of the Spectacle, a state in which commodity fetishism's ”spectacle” had reifacted all human relations.

.jpg)

The concept of Warenfetischismus, Commodity Fetishism, was coined by Karl Marx in an effort to describe how Europeans view consumer goods as ”things which, by their characteristics, satisfy all forms of human needs.” Goods have become sources of human satisfaction and people no longer understand that they really are – results of how human labour has transformed natural resources into consumer goods. Our unwavering desire for goods and services has turned them into something desirable, something almost divine, endowed with an existence of their own, beyond our everyday lives: