Blog

För mig är läsande och skrivande en svårbemästrad drift, en källa till harmoni och glädje. Det tar dessvärre mycket tid i anspråk. Om det gav en inkomst skulle verksamheten rättfärdigas och lyckan vore fullständigt. Inte minst genom att jag för min närmaste omgivning därmed skulle kunna förvandla begäret till en välgärning för allas bästa. Nu känns det ofta som om skrivandet är en självcentrerad, skamlig brunst som kräver sitt utlopp, men måste utövas i hemlighet.

Om jag inte skriver och läser blir jag rastlös. För mig är Writers´ Block ett okänt begrepp, antagligen drabbar det enbart etablerade författare, sådana som har författandet som levebröd. Det måste dock röra sig om ett fåtal individer som kan försörja sig på ett författarskap. Dessutom har jag läst en mängd skildringar av hur författare genom sin oförmåga att skriva har drivits in i alkohol- och drogmissbruk, blivit hustru- och barnmisshandlare eller funnit frid och säkerhet i genomgripande, men ofta relativt kortlivade, religiösa upplevelser. Att förbli författaramatör är säkerligen tryggast.

För en amatör som jag hägrar emellanåt drömmen om ett litterärt genombrott, ett erkännande som skulle möjliggöra en tillvaro där mitt skrivande ger en dräglig inkomst och därmed trygghet för mig och min familj. Kändisskap och beundran, Andy Warhols söndertjatade bonmot om en längtan efter 15 minutes of fame, femton minuters kändisskap, är mig däremot främmande.

En och annan gång har jag skickat ett romanmanus till de svenska förlagsjättarna, enbart för att som tusentals andra förhoppningsfulla skribenter efter ett par månader få ett standardavslag. Från vilket förlag det än må vara är det i allmänhet mer eller likalydande:

Hej,

Vi har nu läst ditt manus och måste tyvärr meddela att vi beslutat oss för att inte anta det. Konkurrensen är mycket stor och det är enbart en liten del av de insända manuskripten som kan antas för utgivning.

Lycka till

Givetvis utan underskrift. Meddelandet är tydligt och klart. Det står skrivet på väggen - Mene mene tekel u-farsin ”du är vägd på en våg och befunnen för lätt”. Andra är bättre, du duger inte. Fråga inte varför, det ställer enbart till besvär för dig och för oss.

Förlagen bedyrar att alla manus läses, men ”på grund av den stora mängden manus vi får in kan vi endast undantagsvis ge personliga kommentarer.” Detta är givetvis en lögn. Även små förlag får in stora mängder av såväl oläsliga som relativt drägliga manuskript, givetvis kan den ensamme förläggaren, eller hans team av förlagsredaktörer, enbart kasta en hastig blick på dem och efter någon minut avgöra deras eventuella värde, något som i allmänhet bedöms vara ringa.

Manuskript från etablerade författare, eller deras agenter, kändisar och personliga bekanta till förlagsägare, ges givetvis en större uppmärksamhet. Jag har en och annan gång hamnat i kommittéer som bedömt skriftliga alster, i allmänhet ansökningar om forskningsmedel. Eftersom jag själv har skrivit och sänt in sådana, fått en del godkända och andra godtyckligt avslagna, brukade jag läsa andras alster relativt noggrant. Då jag var ung och grön skrev jag väl genomtänkta och noggranna avslag. Det var ett misstag. Främst krävde sådant mycket arbete och snart fann jag att de förtvivlade mottagarna grep efter dessa halmstrån och genast kontaktade mig med upprepade vädjanden, försäkringar om förbättringar och värst av allt – klagande litanior, hotelser och förolämpningar, till och med förtäckta hot om självmord. Mest plågsamt var att jag förstod de refuserades känslor, deras förtvivlan. Snart begränsade jag mig till kortfattade avslag, kliniskt befriade från omdömen och ansvar, förvirrande lika exemplet ovan. De refuserade stackarna hörde då inte av sig och min tillvaro och mitt samvete blev betydligt lättare.

Nästan lika irriterande som förlagsavslag är de förnumstiga råd till blivande författare som finns på förlagens nätsajter, eller som inom universitetens eller högskolornas ”skrivarskolor” presenteras av halvusla författare, medan en och annan hyfsad författare skriver en bok om sitt skrivande.

En besvikelse bland de senare var Olof Lagercrantz Om konsten att läsa och skriva, intressant var dock Stephen Kings Att skriva: En hantverkares memoarer. King har en förmåga att finna ett kamratligt tilltal, ett berättande som ställer honom på läsarens nivå och som stöttas av hans egen produktion, som är ytterst ojämn - från bottennapp till mästerverk. Kings smak är även den beundransvärt bred – filmer, musik och litteratur längs hela skalan från skräp till klassiker. För King faller det sig också helt naturligt att skriva om författande – ett stort antal av hans skräckberättelser handlar just om skrivandets dilemma, kanske är det hans mest genomgripande tema.

Varför gillade jag inte Lagercrantz bok? Det var länge sedan jag läste den och det kan hända att jag ändrar uppfattning om jag läser om den, men då tyckte jag mig ana doften av författarposerande. Rollen spelad av honom själv. ”Jag är en lyckad och etablerad författare. Jag vet. Jag är professionell. Jag har något att lära ut.” Konstnärens, skaparens självgodhet lyste igenom.

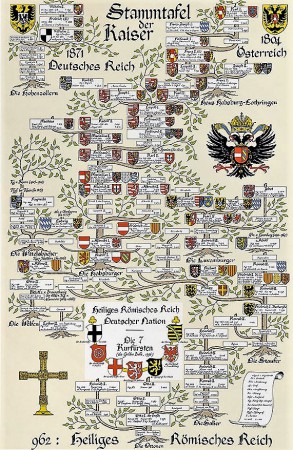

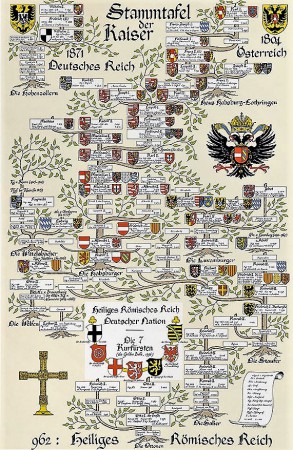

Högmod är en vanlig författarsynd, dessutom är det en av de sju dödssynderna – högmod/fåfänga (superbia), girighet (avaratia), otukt (luxuria), avund (invidia), frosseri (gula), vrede (ira) och lättja (acedia). Vi har begått dem alla, i högre eller mindre grad. Dessa försyndelser tycks utgöra en del av vår mänskliga natur.

Först på listan, och på goda grunder, står högmodet. Det har en tendens att omfatta de övriga synderna. Jag antar att mitt skrivande kan betraktas som en form av högmod. En demonstration av mitt kunnande. En svaghet jag delar med många lärarkollegor. Själv vill jag givetvis betrakta det på ett annat vis – en okontrollerbar drift utan dolda agendor, en träning av min skrivförmåga, en minneslista som kanske kan komma till användning. Men, inom konstbegreppet, såväl litterärt som konstnärligt skapande, finns ett mått av övermod. Är det inte förmätet att försöka efterbilda, eller till och med sträva efter att överträffa, något som redan omger oss?

Det tycks som om tänkare och författare sedan flera tusen år tillbaka har uppfattat högfärd som en grundläggande mänsklig egenskap. Att sträva efter att framstå som förmer än andra, att uppföra sig som en gud – allvetande, maktfullkomlig. Att försöka bli odödliggjord genom sina handlingar betraktades av flera av de antika grekerna som en form av storhetsvansinne. En synd som hotade att rubba världsordningen. Bättre var att känna vördnad och ödmjukhet inför gudar och människor, sådant renade själen.

Aristoteles definierade hybris som en akt som skämmer ut en medmänniska, eller förminskar hennes värde. Någon som är ansatt av hybris behöver inte känna sig hotad eller angripen, tillståndet är enbart ett resultat av glädjen av att känna sig överlägsen andra.

Den ursprungliga och exakta betydelsen av ordet är svår att finna, men den var uppenbarligen kopplat till uråldriga hedersbegrepp, till social status, d.v.s. en individs ställning inom en grupp och har därmed hade hybris ett intimt samband med begrepp som makt och värde. Ju värdefullare en grupp individer anser dig vara, desto större heder och ära tilldelar den dig. Att bli beundrad, fruktad och mäktig. Att vara flockens dominerande hanne, en alfahanne, är något som de flesta flockdjur tycks eftersträva. Aristoteles skriver:

Anledningen till det välbehag som förödmjukande människor känner är att de genom den dåliga behandling de ger andra tycker sig bli överlägsna. Det är därför de unga och de rika tenderar att förnedra andra, genom förolämpningar känner de sig förmer än andra; det finns förakt i en förolämpning, att förakta en annan människa är liktydigt med att försvaga henne. Ty det som saknar värde, saknar även nytta.

Kristendomen anser i allmänhet att superbia, högmod/fåfänga är en ytterst allvarlig synd. Kanske alla synders moder? Läran om de sju onda tankar som ständigt ansätter oss och som måste bekämpas om vi skall uppnå salighet tycks ha uppkommit bland egyptiska ökeneremiter, de så kallade Ökenfäderna. Den som först skrev ner dem tycks ha varit en viss Evagrius Ponticus (345 – 399 e.Kr), som föddes i en liten stad i norra delen av nuvarande Turkiet, men slutligen hamnade som asket i de egyptiska öknarna.

Evagrius hyllades en gång av det numera bortglömda prästerskapet i Konstantinopel. De beundrade honom för hans vältalighet och djupa kunskaper. Enligt Evagrius förvrängde egenkärleken synen för honom. Högmod förde honom in i syndens garn, fick honom på fall och gjorde att han smakade alla de laster han senare räknar upp. Det var orsaken till att han placerade högmodet främst i sitt syndaregister. I skam och förtvivlan sökte Evagrius slutligen ensamhet och självplågeri i obanade vildmarker – men, han kunde inte avhålla sig från att skriva om det.

Under Medeltiden växte spekulationerna kring de grövsta synderna sig allt starkare och fick slutligen, som så många andra tankegångar, sitt förnämsta konstnärliga och intellektuella uttryck i Dante Alighieris Divina Commedia, som han skrev mellan 1308 och 1321. Framställd som en detaljerad dröm skildrar den märkliga diktcykeln hur Dante i sällskap med den romerske poeten Vergilius, och sin drömkvinna Beatrice, färdas genom Helvetet (Inferno), Skärseldsberget (Purgatorio), och genom himlarna fram till Gud.

Eftersom det rör sig om en dröm vill jag påstå att Divina Commedia utspelar sig bland tankarna inne i Dantes huvud och därmed blandas, bearbetas och ordnas spekulationer, läsefrukter, känslor av kärlek, hat, sorg, välbefinnande och längtan, vardagliga upplevelser och besvikelser, mytologi och teologi. Liksom i en dröm tar sig allt detta konkreta uttryck och blir till händelser som utspelar sig inom olika miljöer. Dantes Purgatorio, Skärseldsberg, är således både en plats och en tanke.

Om Inferno, Helvetet, var en plats där syndarna i all evighet straffades för begångna missdåd så är Skärselden mer en plats där du renas från syndiga tankar och drifter så att du därigenom förbereds för ditt inträde i Paradiset.

Som alla djupgående förändringsprocesser är tillvaron i Skärselden långvarig och plågsam, men det rör sig om en helt annan plats än Helvetets tunga mörker och förtvivlan, över vars ingång det stod skrivet Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch´intrarte, Lämna allt hopp ni som går in.

Plågorna i Skärselden skiljer sig från de som drabbar människosjälarna i Helvetet. På Skärseldsberget lever hoppet, plågorna har ett syfte. Som i ett behandlingshem för drogmissbrukare renas din kropp och själ under plågsamma former från syndens skadliga gifter. Över själarnas kvalfulla tillvaro välver sig en öppen himmel, över vilken sol, måne och stjärnor rör sig. Tiden går; dagar följs av nätter. I Helvetet råder evig natt och tröstlös plåga.

Men liksom i Helvetet vilar skuldabördan tung över skärseldstillvaron. Och den största allomfattande synden, den som gett upphov till allt annat elände, är övermodet/fåfängan. Övermodets egenintresse skapar maktfullkomlighet, självgodhet och förakt för andra människor.

I Helvetet ligger Superbia, högmodet, bakom alla synder, genomsyrar allt. Därför finns ingen specifik plats där maktfullkomliga egoister plågas. Däremot finns en sådan avdelning i Skärselden, som fungerar som ett slags vårdhem för syndare, där synden måste diagnostiseras och åtgärdas inom en specialavdelning.

Plågoanstalten för egoistiska maktmänniskor och självgoda konstnärer är den första avdelning du kommer till om du besöker Skärseldsberget. Då syndaren blivit botad från högmodets värsta symptom förs hen i tur och ordning till de andra vårdinstanserna – invidia, ira, acedia, avaratia, gula och luxuria. Behandlingen inriktar sig alltså på att bota dödssynderna, en efter en.

I Helvetet är det bestraffning som reglerar plågorna, i Skärselden är däremot kärlek/medlidande den princip som styr all verksamhet. Det gäller att befria kärleken från sina skadliga avarter. Exempelvis så behandlar de tre första avdelningarna tankar och handlingar baserade på missriktad kärlek, sådan som uppkommit genom egenkärlek, avundsjuka och hat. En annan avdelning är inriktad på att bota lättja och oföretagsamhet, alltså synder som hindrat dig från att visa kärlek och göra goda gärningar. De sista tre behandlingsavdelningarna är ägnade att komma tillrätta med missriktad energi, som då kärlek koncentrerat sig på att tillfredsställa det egna begäret, utan någon större tanke på andras välbefinnande (girighet), eller då den inriktats mot ett överdrivet gynnande av kroppsliga behov (frosseri), eller då tillfredställandet av sexuell lust har varit den drivande bakom kraften bakom kärleken (kättja).

På flera ställen i sitt verk erkänner Dante att han pressats hårt och plågats av sitt högmod. Att han trott sig vara förmer än andra; skickligare, kunnigare och bättre än samtida diktare. Detta med goda skäl - Dante Alighieri var en beundrad författare, en skickligare skald än samtliga konkurrenter. Det hindrade dock inte att hans självuppskattning plågade honom, det tröttnade han i varje fall inte på att bedyra inför sin omvärld. Färden genom Aldilà, Den Andra Sidan, var ett försök att råda bot på missförhållandet. Syftet var att göra Dante Alighieri mer ödmjuk, göra honom till en bättre och mer kärleksfull kristen.

Efter sin mycket krävande vandring genom underjorden når Dante och Vergilius tidigt på morgonen den elfte april år 1300 Skärseldsbergets strand. De har kommit dit genom en underjordisk tunnel och befinner sig nu på jordklotets andra sida.

Även om hans världsuppfattning var medeltida ansåg Dante att jorden var rund och att den andra hemisfären var täckt av en ocean, det enda landområde som fanns där var det väldiga Skärseldsberget, som reste sig i havets mitt. Dante och hans följeslagare andas ut och känner sig lättade i den friska morgonluften. Vergilius tvättar Helvetets sot och smuts från sin ledsagares ansikte och tillsammans blickar de upp mot himlen över dem:

Mild såsom österländsk safir i färgen

och genomskinlig upp till första kretsen

stod en seren rymd framför mina blickar

och fick dem ånyo att känna glädje

så snart jag sluppit ur den döda luften

som hade kvalt mitt bröst och mina ögon.

Längs bergets stränder möter de två poeterna själar som ännu inte släppts in för att renas i Skärselden. Det är syndare som strax innan döden har ångrat sin ogärningar, till och med sådana som med våld tvingats att bekänna sina synder, men som förlåtits av Gud. De har nått fram till Skärseldsbergets fot, men måste vänta på tillåtelse att genomgå den behandling de skall utsättas för.

Efter att ha passerat porten till berget och klättrat uppför genom en smal och stenig stig når Vergilius och Dante vid tio-tiden på morgonen en väg som slingrar sig uppåt längs Skärseldsberget, den är lätt att vandra längs, men inte speciellt bred – den motsvarar tre ”manslängder”, vilket enligt tidens mått skulle motsvara fem meter.

Som inspiration för de syndare som släpar sig fram längs bergsvägen är den kornisch (Dante kallar Skärseldsbergets avsatser för cornice, d.v.s. ”vallar” eller ”lister”) där de övermodigas själar luttras kantad av utsökta marmorreliefer, som skildrar olika hjältars medlidsamma och goda gärningar, alltmedan själva vägens yta visar hur övermodiga människor, hjältar och gudar har bestraffats. Orsaken till att sådant skildras på vägbanan blir Dante snart varse efter det att han på avstånd sett en grå massa närma sig. Först begriper han inte vad det är som rytmiskt rör sig framåt, det är först då de kommer fram bredvid honom som han upptäcker att det är nakna syndare som bär på väldiga stenblock. Genom att tyngas av de tunga stenbumlingarna lär sig de tidigare så förmätna egoisterna ödmjukhet.

Dante böjer sig ner för att se de plågade människornas ansikten och blir då igenkänd av en nyligen avliden vän, Oderiso från Gubbio, en på sin tid välkänd miniatyrmålare som var verksam i Paris, men som numera i stort sett enbart är ihågkommen genom Dantes omnämnande av honom i Purgatorio. Det är nästan som om Dante visste att hans vän skulle bli bortglömd i framtiden. Oderiso beklagar sig:

En ryktbarhet har gräsets färg som kommer

och går; och samma makt får det att blekna

som lockar det att spira grönt ur jorden.

Oderiso är väl medveten om att hans ryktbarhet kommer att försvinna och bland konnässörerna ersättas av den store mästaren Cimabue, som snart dock kommer att förblekna vid sidan av Giottos mästerskap, som sedan kommer att överskuggas och glömmas bort då nya konstnärer föds. Dante inser att glädjen över att vara beundrad och välkänd är övergående och betydelselös med tanke på den evighet som väntar oss efter döden. Han svarar Oderiso:

En stor böld sjunker ihop i bröstet

vid dina ord, som väcker i mitt hjärta

sann ödmjukhet.

Dante förstår nu att de högmodigas bestraffning består i att både tyngas av stenblocken och tvingas ha sina blickar riktade mot marken, vars bilder ständigt påminner dem om meningslösheten i att låta sig yvas över sin egen förträfflighet. De påminns också om att deras nuvarande plågor enbart är början på den långa väg, kantad av Skärseldsbergets skilda plågor som väntar dem innan de kan nå fram till Paradisets portar. Tid och erfarenhet slipar ner högmodet, som är som störst hos kaxiga ungdomar och de som har makt och myndighet.

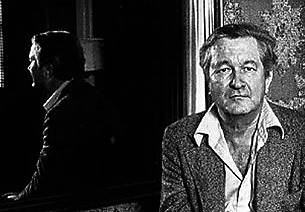

Ungdomlig dumdristighet och litterärt högmod speglas utmärkt i inledningskapitlet till William Styrons roman Sophies val, där författarens alter ego, Stingo, får jobb som förlagsredaktör på McGraw-Hill i New York. Liksom Styron, nyutexaminerad från litteraturstudier vid Duke University i North Carolina, blir den tjugotvå-årige Stingo till en början överväldigad av sin roll som litteraturdomare vid ett stort, välkänt förlag. Med god aptit kastar han sig över manuskripthögarna som tornar upp sig på hans skrivbord.

Stingo uppfattar sig som en förfinad estet med exemplarisk kännedom om vad som är bra och dålig litteratur, likt den engelske artonhundratalsdiktaren Matthew Arnold betraktar han sig som ett destillat av engelsk bildning, med rytmisk instinkt och en klarsynt uppfattning om författandets språkliga trollkraft.

… genomdränkt som jag blivit av engelsk litteraturhistoria var jag likt Matthew Arnold brutalt krävande i min förvissning om att det skrivna ordet kräver högsta allvar och sanning. Jag behandlade dessa patetiska resultat av tusentals främlingars ensamma och bräckliga förhoppningar med samma myndigt och abstrakta avsky som när en apa som plockar ohyra ur sin päls. Högt upp i min inglasade modul på McGraw-Hill skyskrapans tjugonde våning [...] öste jag förakt över [...] de tragiska tirader som växt sig höga på mitt skrivbord, samtliga hopplöst nertyngda av förhoppningar och klumpfotad syntax.

Stingo kan inte minnas om han under sina fem månader på McGraw-Hill rekommenderade något manus för publicering. Samtliga som kom i hans väg föll offer för hans kritiskt granskande blick.

Med tiden överväldigades han dock av grymheten i sin hantering, speciellt efter det att en väderbiten, grovhuggen bonde från North Dakota, med det märkliga namnet Gundar Firkin, personligen dök upp i hans modul. Gundar hade med sig två resväskor och en pappersbunt med inte mindre än 3 850 ark, som visade sig utgöra ett versepos om Harald Hårfagre. Omsorgsfullt och felfritt handskrivna på ett ohjälpligt föråldrat, högtravande språk.

Den överrumplade Stingo bad den förhoppningsfulle Gundar ta in på ett hotell medan han läste det väldiga manuskriptet. Efter att ha stavat sig igenom ett antal svårförståeliga versrader insåg Stingo att manuskriptet var en svårbedömd katastrof. Efter ett par dagar svarade han motvilligt på Gundars enträgna telefonförfrågningar med beskedet om att McGraw-Hill såg sig oförmögna att ge ut det väldiga verket och Gundar försvann ur hans liv.

Droppen som fick bägaren att rinna över och få Stingo att inse att han inte dög som förlagsredaktör var när han refuserat Thor Heyerdals Kon-tiki och då den efter att ha blivit antagen av ett annat förlag månad efter månad höll sig kvar som nummer ett på bestsellerlistorna.

William Styrons förståelse och sympati för refuserade författare gjorde honom dock inte speciellt ödmjuk efter det att han blivit en hyllad och berömd författare. Styrons dotter har i en biografi skildrat hur hennes far plågade sin familj genom sitt alkoholinfluerade dåliga humör, plågsamma writer´s block och ständiga krav på respekt och lugn för att ostörd få utöva sitt författarskap.

Då hans organism oväntat reagerade på hans supande med en våldsam allergi mot alla former av alkohol hamnade Styron i nattsvart depression. Han lyckades dock ta sig ur den och skrev Ett synligt mörker: minnen av vansinnet, en bok som blev populär inte minst genom att den uppmärksammade att depression är ett livsfarligt tillstånd som kan leda till självmord. Även om Styron trodde att han genom att skriva om och göra sitt tillstånd känt kunde övervinna sin ångest fick under de sexton år han hade kvar att leva flera återfall av svår depression, alltmedan han likt så många andra välkända författare och konstnärer fortsatte vara självcentrerad och lynnig.

En lättsammare men inte mindre dyster skildring av förlagsvärlden än den som William Styron gav i Sophies val är Terry Southerns självbiografiska The Blood of a Wig, Blodet från en peruk. Southern var på sin tid en framgångsrik journalist och manusförfattare. Han skrev bland annat manus till Dr Strangelove och Easy Rider och en mängd sketcher för Saturday Night Live. I The Blood of a Wig berättar han om hur han i sin ungdom sjönk allt djupare ner i ett okontrollerbart drogberoende. I allt sitt elände är dock skildringen sorglöst och slagfärdigt skriven.

Southern berättar hur han hamnar på ett litterärt magasin där han dagligen tvingas bedöma ”en otrolig mängd manuskript, ungefär två hundra varje dag.” De når honom sorterade i enlighet med två kriterier: 1) manus som skickats in av agenter, d.v.s. att de förmedlas av ombud för olika redan erkända författare och 2) sådana som kom in direkt från författarna.

Förhållandet var trettio mot ett, till förmån för den senare bunten [d.v.s. manuskript insända av författare]. Den utgjorde en gigantisk trave och kallades för ”skithögen”. Den innehöll alltid en mängd returfrimärken – som jag tog hand om och omgående kunde lösa in för att komplettera min veckolön med mellan sju och åtta dollar. Alla andra uppfattade skithögen som någonting avskyvärt motbjudande.

Då Southern erbjuder att befatta sig med ”skithögen” säger hans kollegor att han är spritt språngande galen. Ingen som är vid sina sinnens fulla bruk ägnar dyrbar tid åt att frivilligt läsa sådan smörja. Southern tror dock till en början att det i skithögen möjligen kan dölja sig en och annan blivande Faulkner eller Hemingway och börjar systematiskt gå igenom de oönskade manuskripten.

Efter ett par dagar ger han dock upp sitt sökande och refuserar sedan på löpande band allt som kommer i hans väg. Snart lägger han åt sidan alla manus vars författare presenterar sig med ett ”Herr”, ”Fröken” eller ”Fru” framför sina namn, sedan får de sällskap av författare som använder sig av titlar, Ph.D. M.D. och liknande. Så bestämmer Southern sig för att alla som har mittinitialer i sina namn är värdelösa författare. På ett tidigt stadium har han redan förkastat alla manuskript som har idiotiska eller fantasilösa titlar.

Eftersom Southern får betalt för varje skriftligt utlåtande om ett manus börjar han fantisera ihop omdömen, baserade på författarnamn och titlar, väl medveten om att ingen kommer att läsa de refuserade originalmanuskripten. Southern dövar sitt samvete och ointresse för sina arbetsmarkerande insatser med alkohol och droger och berättelsen övergår efterhand till en detaljerad skildring av hans varierade missbruk.

Det är inte att undra över att flera av de författare som passerat de väl- eller slumpmässigt bevakade portar som öppnar sig mot publicering och kanske även - under över alla under - litterär berömmelse, betraktar sig som övermänniskor, speciellt om de vunnit tillträde till Parnassens Lyckorike, där de kanske till och med kan försörja sig på sin konst. En plats som enligt patetiska medlemmar av den krympande Svenska Akademin är

en geniernas tummelplats där landets ledande författare, skådespelare och musiker samlas för att dricka vin, framträda och lyssna till varandra.

Utan några namns nämnande är jag övertygad om att en och annan av Sveriges kulturpersonligheter har fallit offer för sitt högmod och bekymmersfritt deltar i dansen kring stipendiernas och privilegiernas guldkalv. Om den verksamheten är genusrelaterad eller inte har jag ingen bestämd uppfattning om. Jag har funnit högmod och maktmissbruk hos såväl kvinnor som män och tror exempelvis inte att Akademins förra direktör, Sara Danius, var offer för några manliga ränker, lika lite som jag tror att Horace Engdahl har rent mjöl i påsen.

Svenska Akademin är förvisso en unik och märklig institution. Jag är övertygad om att den fyller en viktig funktion för Svenska Språkets stadgande ock upodlande, med sin ordlista och ordbok, samt förvaltandet av stipendier och priser. Samtidigt kan jag dock inte undgå att ana att den även är ett sällskap för inbördes beundran, vars medlemmar genom organisationens exklusivitet och förmögenhet löper faran av att falla offer för högmodets grova synd. I varje fall tror jag att en och annan medlem gjort det, något som inte att undra på om du blivit invald i ett illustert sällskap som har som måtto Snille och smak. Betyder det då inte det att du blivit utvald emedan du är en person som anses ha just de ädla egenskaperna?

Ibland undrar jag om den förre ständige sekreteraren inte är offer för sin fåfänga. I så fall kan det hända att han lever farligt. Ett ordspråk säger som bekant att högmod går före fall. Horace Engdahls före detta hustru, Ebba Witt-Brattström, som antagligen även hon är något anfrätt av högmod, antyder i varje fall att exmaken lider av självgodhet:

När han sen blev det han kallar upphöjd, invald i Svenska Akademien, då tyckte jag det var bra, då fick han glänsa. […] Jag har varit akademikritisk i hela mitt liv. Jag tycker att det är trist att Sveriges kulturliv har ett litet gäng som delar ut 25 miljoner årligen till folk de gillar. Och jag trodde aldrig att han skulle falla rakt in i det där egenkära träsket.

Taylor Hackford skildrar i sin film Djävulens advokat från 1997 hur Djävulen manipulerar mänskligheten. Filmen vinner mycket genom Al Pacino, som briljerar i rollen som en mångkunnig och obesegrad Mörkrets Furste. I skepnad av stjärnadvokaten John Milton rör sig Djävulen som fisken i vattnet bland New Yorks glitterati, gödd och respekterad genom en förmögenhet skapad medelst allsköns kriminell verksamhet, samt andra mer allmänt accepterade verksamheter som vapenindustri och miljöfarlig livsmedelsproduktion. Det är genom sin ”favoritsynd” – vanity, högmod/fåfänga, som Djävulen lockar till sig medarbetare och utser sina offer.

Filmen inleds med hur en ovanligt framgångsrik ung advokat, Kevin (spelad av Keanu Reeves), som aldrig förlorat en rättsprocess, försvarar en matematiklärare anklagad för att sexuellt ha ofredat flera tonåriga elever. Under processens gång blir Kevin övertygad om att läraren är skyldig, men för att inte förlora förtroende och anseende som obesegrad brottmålsadvokat fortsätter han sitt skickliga försvar av den antastande läraren och vinner målet.

Detta öppnar för Djävulen, alias John Milton, ägare till New Yorks mest framgångsrika advokatfirma. Filmen handlar om fri vilja. Det är genom våra val vi trasslar in oss i Djävulens garn. Genom att offra vårt samvete för det välbefinnande som högmod och fåfänga skänker lockas vi att agera som vi gör. För vårt högmods skull är vi beredda att skada våra medmänniskor, till och med de som står oss riktigt nära.

John Milton offrar en av sina närmaste medarbetare. Korrupt och karriärsugen blir Eddie Barzon skadlig till och med för Djävulen och denne låter ett par demoner i form av två uteliggare klubba Barzon till döds. Inför Kevin försvarar John Milton sitt dåd genom att förklara att män som Eddie Barzon finns det i överflöd. Djävulen har själv skapat dem genom att låta dem uppslukas av sin egen fåfänga, sin befordringshunger, viljan att vara förmer än andra:

Eddie Barzoon - ta en bra titt på honom, för han är urtypen för nästa årtusendes människa! Män som han, det är inget mysterium var de kommer ifrån. Du ökar den mänskliga aptiten till en nivå där de med sina omättliga begär kan splittra atomer. Du bygger egos stora som katedraler. Till varje lysten impuls kopplar du audio-visuella verkligheter. Smörjer banala drömmar med dollargröna, guldpläterade fantasier tills varje mänsklig varelse slutligen förvandlas till en aspirerande kejsare, blir sin egen gud, och vart kan du gå därifrån?

Filmen blir alltmer absurd alltmedan John Miltons sanna natur uppenbaras och advokatberättelsen utvecklas till en regelrätt skräckfilm med verkliga demoner och en djävul som försöker skapa sig en Antikrist genom att para sig med vanliga kvinnor. Men efter en blodig klimax befinner vi oss åter på toaletten till Domstolen i Florida där den unge advokaten Kevin beslutar sig för att inte företräda och försvara den flickantastande läraren. Var hela historien inget annat än en dröm, en parallellhistoria som inte blev verklighet?

Kevin återvänder till rättssalen och till allas förvåning får han sin klient dömd för otukt mot barn och utsätter sig därmed för möjligheten att mista rätten att representera klienter inför domstol. I den sista scenen skyndar Kevin sig ut från rättssalen. Tillsammans med sin hustru, Mary Ann, springer han nerför en trappa då de hejdas av en journalist, Larry, som ropar år Kevin och ber honom hejda sig för att ge honom en kort intervju. Kevin svarar att det vill han inte:

– De kommer att ta ifrån mig rätten att agera inför domstol, Larry. Det kan du läsa om sen!

Mary Ann hejdar sig och frågar Larry:

– Vänta en sekund, kan de verkligen göra det?

– Inte efter det att jag fått igenom min historia, försäkrar journalisten och vädjar åter:

– Du måste tala, Kevin. Ge mig en exklusiv intervju. Det här är kabel-TV. Det blir stort, Sixty Minutes! Den här historien måste ut. Det är du! Du är en stjärna!

Kevin skakar blygsamt på huvudet, ler smickrat men låtsas likväl som om han är ovillig att gå med på det lockande förslaget. Mary Ann viskar vädjande:

– Baby.

Kevin ropar upp till Larry:

– Kör till! Ring mig i morgon bitti!

– Överenskommet! svarar Larry triumferande. Det blir det första jag gör!

– Vi ses! Ropar Kevin och vinkar avsked till journalisten som ler knipslugt alltmedan hans anletsdrag förvandlas till John Miltons. Djävulen konstaterar:

- Vanity, definitely my favorite sin. Fåfänga, utan tvekan min favoritsynd.

Vi är alla möjliga offer för högmodet. Många av oss söker det genom jakt efter berömmelse – inom sport, underhållning, författande. Flera av oss hoppas kunna skilja oss från mängden genom att våra skriverier antas av en förlagsjätte. Då öppnas berömmelsens pärleportar. Fåfänga skapas eller faller beroende på om våra alster antas eller refuseras. Bäst är nog att undvika hela cirkusen och betrakta sig som en författaramatör, se skrivandet som en hobby, inget annat, en avkoppling som inte är mer dramatisk än golf eller fiske, då blir det ett sant nöje.

Aristotle (1991) The Art of Rhetoric. London: Penguin Classics. Björkeson, Ingvar (1983) Dante Alighieri: Den gudomliga komedin. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur. Bosco, Umberto e Giovanni Reggio (2005) Dante Alighieri, La Divina Commedia: Purgatorio. Roma: Gruppo Editoriale L´Espresso SpA. Hagen, Cecilia (2017) “En separation är som en amputation” Expressen, 26 mars. Southern, Terry (1967) ”The Blood of a Wig” i Shannonhouse, Rebecca (ed.) (2003) Under the Influence: The Literature of Addiction. New York: Random House. Styron, Alexandra (2011), Reading My Father: A memoir. New York: Scribner. Styron, William (1983) Sophies val. Wahlström och Widstrand.

This year our Easter weekend became, at is often is, varied and inspiring. Good Friday – rainy and dark – ended up with the traditional procession in Civitavecchia, an expression of grief over the deceased Christ. It is told that the procession first took place in 899 AD, as a public, joint expression of the harbour town's concerns about the upcoming century and out of fear of an expected invasion of Muslim pirates.

Concerned about past sins and God's forthcoming punishment, hundreds of penitents – men and women – walked along the streets with their faces covered by hoods, with heavy chains fastened to their ankles and burdened by solid, wooden cross. The chains dragged over and rattled against the paving stones, and still do. The tradition is kept alive. After more than one thousand and one hundred years, hundreds of barefoot penitents pass through Civitavecchia's streets and the clattering of their chains mixes with brass bands´ funeral marches.

Some of the hooded, ku-klux-clan-like penitents carry catafalques adorned with sculpture groups representing the lashing of Christ, his crucifixion, the mourning Maria´s and his dead, battered and beaten body. Police officers, carabinieri and town notabilities pass by, profoundly serious in their gala uniforms. The atmosphere is heavy, saturated. Everything is weird, beautiful and tragic.

Easter day dawned with a clear, blue sky. We drove down to St. Peter´s Square where expectant people from all corners of the globe queued in front of security controls, which with each passing year have become increasingly rigorous in fear of constantly mounting threats of terrorism. The controlling policemen and military were polite and friendly, the Vatican visitors patient and calm. Good Friday's weighty atmosphere had evaporated.

While he was sweeping a kind of electronic rod across my body, the mobile phone of the controlling carabiniere rang. With an excusing smile, he interrupted the survey while answering the call:

– Yes, yes, Mom, I'll call as fast as I can. Right now I'm in the middle of my work. Of course we´re coming to dinner. Chiara, as well? Certainly. I´ll call you back as soon as I can. Promise.

"It was my mom," the carabiniere explained, while he nodded as a sign that I was free to continue toward St. Peter´s Square.

The speaker system worked well while various church potentates sang and prayed, though we could not hear a word of what the pope had to say.

- Sabotage, mumbled someone next to me. The Curia is against the man. They have probably tampered with the loud speaking system so we would not be able to hear what the Good Father is telling us. Tradittori, infedele … l'intero pacchetto.

The enthusiastic crowd cheered Pope Francis as he walked down the stairs of St. Peter to enter in the papamobile. Bared from earlier-day bulletproof glass, the vehicle drove among the jubilant crowd. It could be heard where the popular pope passed by, the cheering followed the papamobile around St. Peter´s Square.

"It is as if the Rolling Stones are driving past, commented my younger daughter. I thought of John Lennon's provocative statement: "We are more popular than Jesus." Now maybe Pope Francis might be even more popular than Lennon. As he passed by, I caught an excellent photo of the waving Jorge Mario Bergoglio, God's representative on earth. I also appreciate this smiling man.

After watching the Pope we drove north, to Tarquinia. The Etruscan grave chambers were open and the entry free of charge. We have been there several times before. The small structures built on top of the graves are scattered across a wide field that, by the beginning of the approaching spring, are covered by meadow flowers and lush grass.

A long time ago we once tended Artemis here, the rabbit of my eldest daughter, Janna. When she had grown older, Janna painted a picture inspired by a photo I took of her cradling the beloved Artemis. She gave it to me on one of my birthdays and I brought it to Stockholm, where I kept at my office at Sida, The Swedish Development Cooperation Agency. To my disappointment and great anger the picture was eventually stolen. It was quite good and someone maybe thought it was valuable. Janna now lives with our soon two-year-old grandchild in Prague, though we had brought Esmeralda, our youngest daughter with us to Tarquinia and I took a photo of her where she stands among the greenery under a blue sky.

The darkness and the murals of the burial chambers constituted a sharp contrast to the light and spring above them. Some were quite lugubrious. We wondered why some Etruscans had their grave chambers adorned with frescoes depicting menacing demons. Some monstrous looking creatures flanked fake doors, which had been painted, or constructed, above the actual entrances to some of the burial chambers, probably as attempts to confuse unwelcome visitors, or trick evil creatures.

Most common among these creatures of eternal night was Charun. A hellish demon with pointed ears, bushy eyebrows, frowning forehead, nose like a vulture´s beak, thick lips, fangs and a pointed goat beard. Often his hue is depicted as bluish grey, as to indicate that he is actually a carcass in the first stages of carnal decay. Snakes wrap around his legs and arms, sometimes he is wearing huge wings. In almost all depictions, he carries a hammer, or rather a wooden mallet, probably used to club opponents, or sacrificial victims, to death. Sometimes a nasty smile lingers on the demon's lips.

In my books about Etruscan civilization I read that Charun originally was called something else but he was later provided with a Greek name, the one the used to denominate another demon who brought souls of the deceased across the river bordering The Kingdom of the Dead. The texts described Charun as an apotropaioi, these were creatures protecting humans from evil, scaring away malicious forces. However, I assume that Charun's tasks were more extensive and complicated than that.

At the museum of Tarquinia, which also offered entry free of charge to celebrate the Easter, we came across a sarcophagus that once had preserved the remains of a priest called Laris Pulena. On one side of the stone coffin was a relief showing how two Charun creatures swing their mallets above the head of Laris Pulena. To me it looked like they instead of protecting the priest were in the process of killing him.

In books about gladiators it is often claimed that Roman gladiator games originated from the Etruscans. However, the claim is doubtful. Certainly, there are several tomb murals that seem to depict ritual killings that may have been part of funeral rituals. Most famous is a fresco from a tomb in Vulci, where naked men have their throats slit by elegant, strangely inexpressive executioners, while Charun is observing the killings with his wooden mallet in readiness.

A blue-hued monster appeared in Roman gladiator games, generally described as Dis Pater, Father of the Underworld. His task was to kill injured gladiators with a wooden mallet. Obviously, the creature is no other than Charun in a different shape.

I remember how I and my cousin Erik Gustaf sometime in the early 1960s by our grandfather, were invited to watch Mervyn LeRoys Quo Vadis from 1951, with an extraordinary Peter Ustinov as Nero. After all these years a short scene has stuck with me. When the doomed Christian martyrs are to be released from their dungeon to be torn apart and devoured by lions in front of a jubilant spectator mass, a black-dressed creature ceremonially progresses to the large gate separating the Christians from the arena. He wears a green-greyish mask with pointed ears, protruding eyes and fangs, a thick snake is winding itself around one of his arms. In his right hand he holds a baton with which he knocks on the gate three times, until it opens to release the terrorized Christians. Since I saw Quo Vadis, and afterwards when the monster appeared in my nightmares, I have wondered who that demon could be and it is first now I realise it was Charun in his disguise as Dis Pater.

I guess Charun apparently was far from being, as it has often been argued, a psychopomp, a gentile creature who accompanies the dead to "the other side". He was rather a murderous beast who made sure that the dead were indeed deceased before they were brought into the Kingdom of Death. The Etruscan psychopomp was rather a winged woman, who often is depicted together with Charun. Her name was Vanth and on the mural in Vulci she stands behind one executioner who is slitting the throat of a victim.

Charun is no companion of the deceased, he is rather some kind of bailiff who makes sure that everything is rightly done, that the dead really are dead before being handed over to the awaiting Vanth.

The name of the death god who executed injured gladiators on e blood-stained arenas, Dis Pater, makes me think of the English word dispatcher, which denotes someone who delivers an item, or a person, from one place to another. That word apparently originates from the French despeechier, to liberate, related to the Latin pedica, chain or manacle. It is thus possible to imagine that Charun, in his shape as the gladiator dispatcher Dis pater, by death ultimately freed gladiators from their wretched slavery.

On a vase in Paris, we see Charun waiting beside the Greek hero Ajax, who is piercing his sword through a Trojan warrior. A scene reminiscent of the mural of Vulci, which apparently does not reproduce a gladiatorial battle, but how prisoners of war are executed beside a hero's tomb, like when Akilles in the Iliad by Patroclus´s funeral pyre executes twelve Trojan prisoners of war.

I wonder why the unsavoury Charun is present in so many Etruscan tombs. Why not settle for the beautiful, winged Vanth, who cautiously carries the souls of the deceased to the other side?

Perhaps Charun served as a memento mori, a reminder of our mortality. His presence reminds us that we must take care of our moment on earth, making the most of our lives. Like those representations of time in the shape of Chronos we may be confronted with while strolling through ancient cemeteries.

In the museum of the small town of Sarteano, within the wine district of Montepulciano, we are confronted with the, in my opinion, most scary depiction of Charun. It was found in a tomb discovered as late as in 2003. From the sarcophagus of the deceased, a three-headed worm slithers towards a banquet scene by the entrance to the tomb, where a couple of lively discussing men lay next to each other on a divan.

On the other side of the doorway, a quadriga, a two-wheeled chariot drawn by two lions and two gryphons, is scurrying along the wall. Charun stands at the reins, with his pointed fangs and undulating hair. Most notably, and strangely terrifying, is the shadow that Charun throws upon the wall next to him. Is it the darkness of death that follows us everywhere?

Death is present in the Etruscan tombs, though there is also plenty of life. People are bathing, chasing, fishing, making love, dancing and drinking wine. Dolphins tumble among ocean waves, birds swirl in the air; there are flowers, deer, panthers and lions. Life and vivid colours, unbridled hymns to life and joy.

Especially fascinating are the banquet scenes, depicted with wine, music and dance. Surprisingly, we sometimes find men and women resting on the same couches. Just like on some sarcophagi, where they repose close together.

At several depicted banquets participants hold up eggs, as if they were demonstrating something. Eggs are also displayed during our present-day Easter banquets. Our familiarity with them may make it easy to forget that eggs are loaded with symbolism by representing new life, resurrection and rebirth – cosmos, perfection and harmony.

After coming out into the street by Tarquinia's museum, we found that the town dwellers were waiting for the traditional procession of the resurrection of Christ in all his glory. A brass band was followed by men dressed in blue and with red scarves around their necks, armed with rifles they fired resounding volleys up in the air.

After them came other blue-clad men carrying tree trunks decorated with intricate foliage, weighing more than a hundred kilos. By the end of the procession a group of men carried a catafalque with a heavy statue weighing more than half a tonne and carved in 1832, to replace a similar statue that was probably created in 1635.

The following day, together with our friends, we ate a lamb steak – an Agnello alla Pugliese. A delicious dish with the succulent roast meet placed on a bed of thinly sliced potatoes and spiced, sweet Italian tomatoes, together with lard, herbs and rosemary. I cover the steak with a mixture of olive oil, parsley, grated lemon peel and peccorino cheese. It never fails.

Easter - a feast for life and death. Tragedy and Resurrection. Remembering my parents' death, I was with my mother an hour before she passed away half a year ago, I miss them intensively, keenly feeling the emptiness they have left behind, but strangely enough, no sadness. They gave me a love and joy that stayed with me throughout life. I also think about my own aging and become amazed that it does not scare or torment me. Perhaps because the decay, sickness and other ailments of old age have not begun in earnest yet. I've lost my dense curly hair. My body is caving in, while my belly swells. I have slight difficulties while getting up, or bending down. Though not exceedingly. The memory may fail, but is probably not much worse than before and in my mind I have not yet passed twenty years.

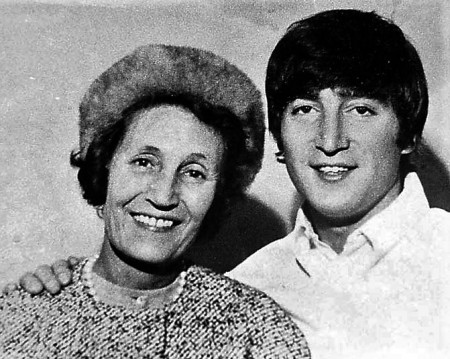

Is my old age similar to the one described depicted in Paul McCartney´s When I'm Sixty-Four? In five months, I will actually become sixty-four years old. It is completely OK. I have most of my life been a blessed man. In spite of annoying misgivings I have assumed that I have been a fortunate man. When I'm a Sixty-Four gleams of harmony and well-being. In that song there is no fear of old age. One of my best friends was in his youth quite obsessed by John Lennon's unique personality, his charisma, genius and creativity, something that has meant he nurtures a certain disregard for Paul McCartney and his music.

- Of those two, Lennon was the genius. What Paul did was composing songs for pubs.

Maybe he is right. When I'm Sixty-Four is fit for warbling, a simple, warm, yet charming and comforting song. In recent days, it has been circling around inside my skull. To my surprise I know the entire text by heart:

When I get older losing my hair

Many years from now

Will you still be sending me a Valentine

Birthday greetings, bottle of wine?

If I'd been out till a quarter to three

Would you lock the door?

Will you still need me, will you still feed me

When I'm sixty-four?

You'll be older too

And if you say the word

I could stay with you

I could be handy, mending a fuse

When your lights have gone

You can knit a sweater by the fireside

Sunday mornings go for a ride

Doing the garden, digging the weeds

Who could ask for more?

Will you still need me, will you still feed me

When I'm sixty-four?

Every summer we can rent a cottage in the Isle of Wight

If it's not too dear

We shall scrimp and save

Grandchildren on your knee

Vera, Chuck & Dave

Send me a postcard, drop me a line

Stating point of view

Indicate precisely what you mean to say

Yours sincerely, wasting away

Give me your answer, fill in a form

Mine for evermore

Will you still need me, will you still feed me

When I'm sixty-four?

The song is almost childishly banal. It is reassuring, pleasant and cheerful. It was a young man who wrote it. Paul was only sixteen years old when he improvised it on his father's piano. He later told that it took shape in his consciousness as some kind of cabaret song, something from a music hall, a ditty that could be heard on the radio.

- When I wrote I'm Sixty-Four I thought I was writing a song for Sinatra.

Everything was not rock´n´roll for young Paul. His father was a musical man who picked out schlagers on the piano and listened to hit songs on the radio and gramophone. In his youth, Jim McCartney had organized and played in a big band - Jimmy Mac Jazz Band.

John Lennon recalled that when their band was still called the Quarrymen, before Pete Best had been replaced by Richard Starky, or Ringo Starr as he called himself, and they still played at The Cavern Club, it happened that Paul was playing When I'm Sixty -Four on the piano and sang it. The other guys in the band liked the song:

We've just wrote a few more words on it, like “grandchildren on your knee,” and stuck in “Vera, Chuck and Dave.” It was just one of those ones that he'd had, that we've all got, really - half a song. And this was just one of those that was quite a hit with us. We used to do them when the amps broke down, just sing it on the piano.

When I'm Sixty-Four became the first song The Beatles recorded for the LP to be their eighth studio album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Despite the harmony and joy it radiates, the sixteen-year-old Paul composed the song in the shadow of his life's greatest tragedy. When he was fourteen, his mother Mary had died in breast cancer. To the last she had been working as a midwife and “home nurse”. For Paul her memory was engulfed in an angelic shimmer and several years after her death he wrote the captivating and strangely comforting Let It Be as a tribute to his deceased mother:

When I find myself in times of trouble

Mother Mary comes to me

speaking words of wisdom:

"Let it be"

And in my hour of darkness

she is standing right in front of me,

speaking words of wisdom:

"Let it be".

Both Paul and John lived in the shadow of the tragic deaths of their mothers. John's mother Julia died in a car accident in 1958. He had previously lost contact with her, when Julia had handed over the custody of her five-year-old John to her sister Mimi. In 1956, John had reconnected with his mother. John's half-sister, Julia Baird, tells in a book about John's complicated relationship with her mother, about how hard he took her death. She quotes her half-brother:

I lost my mother twice. Once as a child of five and then again at seventeen. It made me very, very bitter inside. I had just begun to establish a relationship with her when she was killed. We´d caught up in so much in just a few short years. We could communicate. We got on. Deep down inside, I thought, ´Sod it! I´ve no real responsibilities to anyone now.

Sam Taylor-Wood´s movie Nowhere Boy from 2009 told us about how John and Paul met, how their fabulous collaboration began and developed in the shadow of the deaths of their mothers. It was a good movie and with great expectations I listened to John's Aunt Mimi when she looks out of the window and shouts:

– John, you´re little friend is here!

Geniuses meet and history is created. When John's mother dies and he breaks down during the funeral, he lets his frustration go out over Paul, who assures him that he can imagine how he feels. His mother has also died. In that scene we obtain a foreboding of their future breakdowns and attacks on each other, but also the deep kinship between their souls, with undertones of desperation that occasionally appear in their joint production and especially in Lennon's later, increasingly tragic, existence, with its oscillations between satisfaction, selfishness and desperation.

Neither Paul, nor John grew up in abject poverty, though hardly under any prosperous conditions. Paul's father worked as a supplier of cotton fabrics to various shops and his wife Mary earned more than twice as much as a nurse, something that caused troubles for his family when she died. John's Aunt Mimi first worked as a nurse and then as a secretary, while her husband George first had a dairy shop together with his brother, but then earned a living as bookmaker. George, who was close to John, died when John was fifteen years old. He took his stepfather´s death hard since they had shared many interests, not the least popular music.

The future music geniuses did not grow up in any particular intellectual circumstances, though they had music in their veins and were able to share their musicality with those who were close to them. John had his stepfather and his mother Julia, who sang and played banjo and piano. Paul had his father, who was an able, self-taught pianist with a great repertoire and a profound interest in various kinds of popular music. He taught the son to play and inspired him to compose his own music.

Jim McCartney was thirty-eight years old when Paul was born and thus already fifty-four years old when his son composed When I'm Sixty-Four and sixty-five years when Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band came out. Jim may well have been an inspiration for the song - an older man who had taught Paul to appreciate and play the kind of music on which the song is based. It develops an imagery of a typical English environment, characterised by the mores of a relatively poor, low middle class – cosy evenings, a night at the pub and with friends, Sunday excursions, and caution with money. Let us have a closer look at the text:

When I get older, losing my hair, many years from now. It is where I find myself at the moment. How could the sixteen-year-old Paul McCartney know that his hair could be on the mind of a sixty-four-year-old man? Especially since he once had lots of it, like me and Paul?

Will you still be sending me a Valentine, birthday greetings, bottle of wine? Old flame never dies. We meet an older couple who still give each other signs of their love and affection, for whom the sharing of the contents of a bottle of wine becomes a celebration worthy of a lifelong kinship of souls. I come to think about the old couple in Disney's Up in which Carl and Ellie Fredricksen live a happy life together. Despite the fact that their longing for children is not met, they succeed in preserving their shared youthful dream of going away to a distant, exotic place, an existence and dream that unfortunately transforms Carl into a grumpy old man when his beloved Ellie dies, but the story ends happily – as in all true fairy tales.

If I'd been out till a quarter to three, would you lock the door? Here we find ourselves in England's pub culture, contentment within the fraternity of good ol´friends, albeit with somewhat too many drinks, but this does not prevent a loving wife from condoning minor, actually not too serious transgressions. After decades of fellowship, virtuous married couples know their partners well and can trust that a spouse does not go about committing any major crimes or stupidities.

Will you still need me, will you still feed me, when I'm sixty-four? We need each other. We want to trust each other and share our lives with someone we love, even when we grow older. We want to be well cared for and feel needed. Here too, the sixteen-year-old Paul displays an amazing insight about our hopes for a safe and cosy old age.

I could be handy, mending a fuse when your lights have gone. Here we find ourselves in an immaculate home environment and within safe, traditional gender roles. The husband fixes practical things, takes care of the technicalities, while, through her soft femininity, his wife guarantees an atmosphere of security and warmth – You can knit a sweater by the fireside. Weekly heydays and relaxation are also homely and shared – Sunday mornings go for a ride.

The home is beautiful, the husband is doing his part – Doing the garden, digging the weeds,

Who could ask for more? Well, maybe the economy could be somewhat better, but where trust and love abode we find means for simple, but enjoyable pleasures – Every summer we can rent a cottage in the Isle of Wight. If it's not too dear. We shall scrimp and save.

The old couple´s harmonious way of life is not childless. Unlike Carl and Ellie in the Disney movie, they have enjoyed and still the benefit from an ideal family life and now they revel in their grandchildren who stay close to them, something the lyrics express in a simple and touching manner – Grandchildren on your knee, Vera, Chuck & Dave.

The end of the song, however, proves that it is all a dreamed-up utopia. It is an offer of marriage, which a young man writes to the woman he wants to share his life with:

Send me a postcard, drop me a line

Stating point of view

Indicate exactly what you mean to say

Yours sincerely, wasting away

Give me your answer, fill in a form

Mine for evermore

Will you still need me, you will still feed me

When I'm sixty-four?

Did it all end up well for The Beatles? Did their Utopia turn into a reality? When the song was sung, written and recorded, they were all close:

The Beatles spent their lives not living a communal life, but communally living the same life. They were each other's greatest friends. [George Harrison's ex-wife Pattie Boyd remembered that] "all belonged to each other. George has a lot with the others that I can never know about. Nobody, not even the wives, can break through or even comprehend it.”

They had a lot in common, not just the music, but also their humour and view of life. They came from humble living conditions. They had had a difficult childhood. John and Paul had lost their mothers. Ringo's parents divorced when he was three years old. He had been sickly and experienced an inadequate and insufficient schooling. Nevertheless, he had, like John, had a friendly and musical stepfather, who dedicated a lot of time and interest to his stepson and together with his mother he both sang and played the piano. The one Beatle who apparently had the quietest childhood was Paul, whose mother was a shop assistant and father a bus driver. They encouraged his musical interests and the father bought him a guitar.

Over time, all the Beatles had their fair share of drug abuse and crashed marriages. Over time they slipped away from each other. John and Paul publicly interrupted their friendship, clashed with each other and only occasionally succeeded in provisionally repairing their once so intense and close friendship. They became involved in a difficult, painful and very public display of battle for prestige, independence and recognition. At the same time it became apparent that George Harrison had felt marginalized by John's paternalism and Paul's constant prioritization of his own creations, his music, while Ringo had suffered from an inferiority complexity vis-à-vis the other members of the band, in spite of the fact that The Beatles could not have become The Beatles without Ringo's efforts.

It was only Paul and Ringo who were due to become sixty-four years old and they are now 75 and 77 years old, respectively. John was murdered at the age of 40, while George could, to some extent, experience the utopia in Paul's song. He mostly lived a quiet family life, far removed from John's hectic and public one, cultivating his large garden. At the end of 1999, a terrible tragedy struck him when a madman broke into his home, punctured one lung, while giving him forty stab wounds and a head injury. These injuries may have contributed to the fact that less than two years later, at the age of fifty-eight, George died with lung cancer and a brain tumour.

Did Paul live his utopia? Perhaps, according to his own opinion his marriage to Linda was happy and for regular periods they apparently enjoyed a secluded, harmonious family life on their farm in Scotland. However, in 1998 Linda died of breast cancer, fifty-six years old and like his friend John, Paul occasionally exposed a fragmented and plagued impression.

And the aging? I remember how girls of my age remarked that Paul was "the cutest of the Beatles", but lately I've heard how they have lamented that he has not aged in an "appealing manner". Someone pointed out that he is increasingly resembling an old lady, perhaps Angela Landsbury, who became famous through the TV-series Murder, She Wrote. I do not know if the similarity is particularly eye-catching, you may judge for yourselves:

In some of the movies I have seen, acted by or inspired by The Beatles, I have assumed there are allusions to When I'm Sixty-Four. For example, in the absurd, carefree and animated Yellow Submarine, one scene presents how John accidentally messes up the pointers of a huge clock, causing the submarine to pass through a head full of gears and clogs, entering The Sea of Time, an ocean constituted by old-fashioned pocket watches. The Beatles are aging at record speed while white beards grow out of their faces. As soon as the submarine has safely crossed the sea they become rejuvenated and regain their original age.

The music that accompanies this short glimpse into the future is not, however, When I'm Sixty-Four, but like many other tunes in the movie it is performed by an orchestra and composed by Georg Martin, presenting elements of Indian and classical music, as well as a melody string reminiscent of George´s Within You Without You from Sgt. Peppers's Lonely Hearts Club Band.

Strangely enough, I now find that the movie that makes me associate even more with When I'm Sixty-Four is Richard Lester´s in my opinion quite strange A Hard Day's Night from 1964. Richard Lester has explained that his motivation for making this movie was the liberating lifestyle that The Beatles personified, a kind of playful, liberating anarchism:

The general aim of the film was to present what was apparently becoming a social phenomenon in this country. Anarchy is too strong a word, but the quality of confidence that the boys exuded! Confidence that they could dress as they liked, speak as they liked, talk to the Queen as they liked, talk to the people on the train who 'fought the war for them' as they liked. ... [Everything was] still based on privilege—privilege by schooling, privilege by birth, privilege by accent, privilege by speech. The Beatles were the first people to attack this… they said if you want something, do it. You can do it. Forget all this talk about talent or ability or money or speech. Just do it.

The working class lads from Liverpool were turning the antiquated English class society upside down. They were a fresh breath of air in an old fashioned and cramped England, which would never become the same after having experienced their revolutionary influence.

Scriptwriter Alun Owen, who was fifteen years older than The Beatles and like them a devoted Liverpudlian, spent several days in their company. Paul McCartney later commented on his contribution:

Alun hung around with us and was careful to try and put words in our mouths that he might've heard us speak, so I thought he did a very good script.

Alun realized that The Beatles felt like captives of their own success. They had recently been on a tour in Sweden and when John was asked about his impressions from that trip, he responded: "A train and a room and a car and a room and a room and a room and a room." Already when I as a 10 years old boy saw the movie I became slightly confused by "Paul's grandfather". Who was he really? What did he have to do in a film about The Beatles? His presence was in the movie provided with different, strange explanations. Paul states that his grandfather should accompany them because his mother had explained that it would make him a lot of good since he was "nursing a broken heart". Time after time, The Beatles are questioned: "Who is that guy?" And those who are wondering receive different answers. At one point, George told Paul "That's not your grandfather. I've seen your grandfather; he lives in your house." Paul answers: "That's my other grandfather, but he's my grandfather as well."

"The grandfather" turns out to be a villain and a free-liver, who constantly puts the patience of The Beatles to the test. They are declaring him to be a villain and a “mixer”. He flirts with the girls around The Beatles, fakes and sells their autographs, causing Ringo to end up in a prison cell and generally works havoc on The Beatles´s life. What does this old man's presence mean? Is he an anarchist? A representative of the obsolete class society that The Beatles so effectively punctures? A kind of projection of what they themselves would become in the future?

When the film was made, Paul´s grandparents were not alive and his mother was also deceased. Why did he then let such a strange character appear in a movie where The Beatles play themselves, as well as stating that his mother had asked him to take care of him? Perhaps Paul's grandfather is a kind of a more or less conscious representation of Paul´s father. Henry Brambell who played Paul's grandfather was only fifty-one years at the time, ten years younger than Paul's own father, whom he actually reminded about. At least could Brambell´s looks be related to Jim McCartney´s and Brambell looked much older than he actually was.

However, Jim McCartney was hardly such a slippery character as “Paul's grandfather” and his son often expressed his affection for him. Several of Paul's jazzy compositions remind of music hall compositions and have been perceived as a tribute to his father, who taught his son to appreciate vintage English popular music. Songs such as Your Mother Should Know and Honey Pie, as well as the concept of a somewhat antiquated Liverpool atmosphere that frames Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, may be reminiscent of Jim McCartney´s tastes. Despite all the appreciation Paul showed his father, he did not refute that he was often troubled by his father's overly appreciation of his successes and what he perceived as an exaggerated and self-centred pride in having such a famous son.

Easter, with its messages of death and resurrection, its mixture of despair and hope, made me silently hum When I'm Sixty-four. I am right there now, having lost my parents and with a long life behind me. I hardly live in an utopia like the one a sixteen-year-old Paul McCartney dreamed up in Liverpool, long gone. Nevertheless, I would have loved to be there with its safe warmth and simplicity. Life proved to be considerably more complicated and unpredictable. However, during these Easter celebrations I felt quite at ease and The Beatles song warmed me like the fire by which the woman of the song is sitting knitting. Behind me are experiences I regret and are plagued by. My future continues to be uncertain and insecure. However, joy and gratefulness are also present – due to what I have and what I have received. I will soon be sixty-four years old, a fact that I do not fear. It´s quite OK.

The long and winding road

that leads to your door

will never disappear.

I've seen that road before

it always leads me here.

Leads me to your door.

Baird, Julia (2007) Imagine This. London: Hodder & Stoughton. Davis, Hunter (2009) The Beatles: The Authorized Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. de Grummond, Nancy (2006) Etruscan Myth, Sacred History and Legend. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Museum. Firehammer, John (2015) “The Beatles Are Pent-Up Prisoners of Their Own Notoriety in ´A Hard Day´s Night´, Pop Matters at https://www.popmatters.com/192382-the-beatles-are-pent-up-prisoners-of-their-own-notoriety-in-a-hard-d-2495540861.html Hanks, Patrick (ed.) (1980) Collins Dictionary of the English Language. London & Glasgow: Collins. Welch, Katherine E. (2007) The Roman Amphitheatre: From its Origins tothe Colliseum. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Årets påskhelg var i vanlig ordning omväxlande och inspirerande. Långfredagen – regnig och mörk ledde den fram till en traditionell procession i Civitavecchia, ett utryck för sorgen över den döde Kristus. Det sägs att processionen gick av stapeln första gången 899 e.Kr. och att den arrangerades på grund av hamnstadens oro inför det nya seklet och en väntad invasion av muslimska sjörövare.

Bekymrade över gångna försyndelser och Guds kommande straffdom, vandrade hundratals penitenti, botgörare – män och kvinnor – längs stadens gator med ansiktena dolda av huvor. Tunga kedjor hade anbragts vid de ångerfulla syndarnas anklar och bar på bastanta träkors. Kedjornas rassel mot gatstenarna ljöd långväga kring och gör så fortfarande. Traditionen hålls vid liv. Efter mer än ettusen etthundra år vandrar hundratals, barfota penitenti genom Civitavecchias gator och slamret från deras kedjor blandas med blåsorkestrars begravningsmarscher.

Med böjda huvuden bär ku-klux-klanliknande pentitenter tunga uppsättningar som framställer den piskade Jesus, hans korsfästning, de sörjande Mariorna och hans döda, malträterade kropp. Poliser, karabinjärer och stadens honoratiores passerar förbi, klädda i sina galauniformer och under djupt allvar. Stämningen är tung, ödesmättad och allt är underligt, vackert och tragiskt.

Påskdagen grydde med klarblå himmel. Vi körde ner till Petersplatsens där förväntansfulla männsikor från jordens alla hörn köade framför säkerhetskontrollerna, som för varje år blivit alltmer rigorösa inför stigande hot om terrordåd. De kontrollerande poliserna och militärerna var artiga och vänliga, vatikanbesökarna tålmodiga och stillsamma. Långfredagens lugubra atmosfär hade lättat.

Medan han med en slags elektronisk stav svepte över mig ringde den kontrollerande karabinjärens mobiltelefon. Med ett urskuldande leende avbröt han undersökningen och besvarade samtalet:

– Ja, ja, Mamma, jag ringer så fort jag kan. Just nu är jag mitt uppe i arbetet. Det är klart vi kommer till middagen. Chiara också? Givetvis. Jag ringer, lovar.

– Det var min mamma, förklarade karabinjären medan han nickade och visade att jag kunde fortsätta fram mot Peterplatsen.

Högtalaranläggningen fungerade bra medan olika, kyrkliga potentater talade, men vi kunde inte höra ett ord av vad påven sa.

– Sabotage, mumlade någon bredvid mig. Kurian avskyr honom. De har säkert fifflat med elektroniken så att vi inte skall kunna höra vad han säger.

Den entusiastiska folkmassan jublade då påve Fransiskus vandrade nerför Peterskyrkans trappor för att stiga upp i Papamobilen. Befriad från tidigare påvars skottsäkra glas körde fordonet sedan ut bland folket. Det hördes var den populäre påven passerade, jublet följde papamobilen kring Peterplatsen.

– Det är som om Rolling Stones kör förbi, kommenterade min yngre dotter. Jag tänkte på John Lennons provokativa uttalande: ”Vi är populärare än Jesus”. Nu var kanske påven Fransiskus kanske mer populär än Lennon. Då han for förbi oss fångade jag ett utmärkt foto av den vinkande Jorge Mario Bergoglio, Guds representant på jorden. Även jag uppskattar denne leende man.

Efter att ha sett påven for vi norrut, till Tarquinia. Etruskergravana var öppna och inträdet gratis. Flera gånger har vi varit där. De små husen som byggts över gravarna ligger utspridda på ett fält som i den begynnande våren prunkade av ängsblommor och frodigt gräs.

För länge sedan rastade vi en gång min äldsta dotter Jannas kanin, Artemis, här och jag tog då ett kort av henne där hon kramar om sin kanin. Då hon blev äldre målade Janna en bild baserad på det kortet. Jag fick den på min födelsedag och blev förtjust i den. Jag tog mig med den till Stockholm, där jag satte upp den på mitt kontor på Sida, men till min besvikelse och ilska blev den stulen. Nu bor Janna med mitt snart två-åriga barnbarn i sitt hem i Prag, men jag hade med mig Esmeralda, min yngsta dotter och tog ett kort av henne där hon står bland grönskan under en blå himmel, en vårdag i Tarquinia.

En skarp kontrast mot ljuset ovan jord utgjorde de målade gravkamrarna under blomsterängarna. En del var hemlighetsfullt lugubra. Vi undrade varför etruskerna emellanåt framställde bilder av demoner i sina gravar. De flankerade de falska dörrar som målats ovanför de verkliga ingångarna till en del av gravkamrarna, antagligen för att förvirra såväl verkliga besökare, som ondskefulla varelser.

Vid dessa portar till det hinsides kunde Charun vara framställd. En underjordsdemon med spetsiga öron, buskiga ögonbryn, fårad panna, gamnäsa, tjocka läppar, huggtänder och svart pipskägg. Ofta är hans hy blågrå, som för att visa att han är ett kadaver i förruttnelsens första stadium. Ormar slingrar sig kring hans ben och armar, ibland är han försedd med väldiga vingar. I nästan alla framställningar bär han en hammare, eller träklubba, antagligen använd för att klubba motståndare eller offer till döds. Ibland spelar ett otäckt leende på demonens läppar.

I mina etruskerböcker läser jag att Charun, som ursprungligen hette något annat men sedan försågs med grekernas namn på den demon som i sin skrangliga roddbåt forslar de avlidnas andar till dödsriket, är framställd i gravarna för att tjäna som en apotropaioi. Sådana apotropaioi var gudar eller demoner som tjänade som skydd mot ondskan och för att skrämma bort illvilliga makter. Jag tror dock att Charuns funktioner var mer omfattande än så.

På Tarquinias museum, som dagen till ära även det erbjöd fritt inträde, såg vi en sarkofag som bevarat resterna av prästen Laris Pulenas. På stenkistans sida fanns en framställning av hur två charunfigurer svingar sina klubbor över Laris Pulenas huvud. Det tycks som om de istället för att skydda honom är i färd med att slå ihjäl honom.

I böcker om gladiatorer påstås det ofta att romarnas gladiatorspel finner sitt ursprung hos etruskerna. Påståendet är tveksamt. Visserligen finns det flera gravmålningar som tycks framställa rituellt dödande som tycks ha utgjort en del av begravningsriter. Mest berömd är en gravfresk från Vulci där nakna män får sina halsar avskurna, alltmedan Charun betraktar det hela med sin träklubba i beredskap.

Ett blåmålat monster dyker även upp i de romerska gladiatorspelen, i allmänhet beskriven som Dis Pater, Underjordens fader. Hans uppgift är att med en träklubba slå ihjäl skadade gladiatorer. Uppenbarligen rör det sig här om Charun i en annan gestalt.

Jag minns hur jag med min morfar och min kusin Erik Gustaf någon gång i början av sextiotalet såg Mervyn LeRoys Quo Vadis från 1951, med en oförliknelig Peter Ustinov som Nero. Efter alla dessa år har en kort scen fastnat hos mig. Då de dödsdömda, kristna fångarna skall släppas ut ur sin fängelsehåla för att inför en jublande åskådarmassa slitas sönder av lejon, skrider en svartklädd varelse fram till den stora port som skiljer de kristna offren från arenan. Han bär en grågrön mask med spetsiga öron, glosögon och huggtänder, kring hans ena arm slingrar sig en bastant orm. I handen håller han en stav som han tre gånger slår mot porten, som öppnas för att släppa in de skräckslagna kristna. Ibland har jag undrat vem den där demonen kunde vara och det är först nu jag förstår att det var Charun i sin skepnad av Dis Pater.

Jag anar att Charun uppenbarligen inte var, som det ofta har hävdats, en psykopomp, en varelse som ledsagar de döda till ”den andra sidan”. Han var snarare den som såg till att de döende verkligen var avlidna innan de fördes in i Dödens rike. Psykopomp var snarare den bevingade kvinna som allt som oftast avbildas tillsammans med Charun – Vanth. På fresken i Vulci ser vi henne bakom en bödel som skär halsen av ett offer.

Charun är ingen ledsagare, han är snarare en förrättningsman, bödeln som ser till att allt går rätt till, att den döde verkligen är död innan hen kan överlämnas till den väntande Vanth.

Namnet på dödsguden som avrättade de skadade gladiatorerna på Roms blodindränkta arenor, Dis Pater, får mig att tänka på det engelska ordet dispatcher, som betecknar en person som för ett föremål från en plats till en annan. Ordet finner tydligen sitt ursprung i det fornfranska despeechier, ”att befria”, som har ett samband med latinets pedica kätting/boja. Det går alltså att föreställa sig att Charun i gestalt av gladiatordräparen Dis pater genom döden befriar en gladiator från sitt slaveri.

På en vas i Paris ser vi Charun väntande vid sidan om den grekiske hjälten Ajax, som är i färd med att borra sitt svärd genom en trojansk krigsfånge. En scen som påminner om fresken i Vulci som uppenbarligen inte framställer en gladiatorstrid utan hur krigsfångar avrättas vid en hjältes grav, som då Akilles i Iliaden dödar tolv trojanska fångar vid Patroklos griftefärd.

Jag funderar varför Charuns ruskiga gestalt är närvarande i så många etruskiska gravar. Varför inte nöja sig med den vackra, bevingade Vanth, som varsamt för den avlidnas själ till den andra sidan?

Kanske var Charun ett momento mori, en påminnelse om allas vår dödlighet. Hans närvaro minner oss om att vi måste ta vara på vår stund på jorden, göra det bästa av våra liv. Som de framställningar av Tiden i gestalt av Kronos som vi kan konfronteras med då vi vandrar genom gamla kyrkogårdar.

I muséet i den lilla staden Sarteano i vindistriktet Montepulciano finns den i mitt tycke mest skrämmande framställningen av Charun. Den blev funnen i en grav som upptäcktes så sent som 2003. Från den dödes sarkofag slingrar sig en trehövdad orm bort mot en gästabudsscen vid gravens ingång, där ett par livligt diskuterande män ligger bredvid varandra på en divan.

På andra sidan jagar en quadriga farm, en tvåhjulig vagn förspänd med två lejon och två gripar, vid tömmarna står Charun, med blottade huggtänder och svallande hår. Märkligast, och mest skrämmande, är skuggan som Charun kastar på väggen bredvid sig. Är det dödens mörker som följer oss överallt?

I samma grad som döden är närvarande i de etruskiska gravarna finns livet där. Folk badar, jagar, fiskar, älskar, dansar och dricker vin. Delfiner tumlar kring i havet, fåglar svirrar i luften, där finns blommor, hjortar, pantrar och lejon. Liv och färg, uppenbarligen ohämmade hymner till livet och glädjen.

Speciellt fascinerande är bankettscenerna, rikligt med vin musik och dans. Förbluffande nog finner vi ibland män och kvinnor vilande på samma divaner. Precis som vi på en del sarkofager finner dem vilande tätt tillsammans på sina stenkistor.

På flera bankettscener håller deltagarna upp ägg till beskådande. Även som centrum för nutidens påskfirande har vi kanske lätt för att glömma äggens betydelse som symboler för nytt liv, uppståndelse och återfödelse. För kosmos, perfektion och harmoni.