AI WEIWEI IN PRAGUE: What do I care about others?

One evening in Prague, mid-March, darkness had just fallen over the city. I was on my way to the National Gallery while assuming I had ended up on the wrong tram. It travelled through streets I could not recognize. However, occasionally we passed workers who apparently were welding the tracks and I realized that the trams had been redirected. I was on my way to the opening of an exhibition and was becoming increasingly worried that I would arrive too late.

My eagerness to come in time made me get off one stop too early and the drizzle forced me to sprint up to the museum. Once there, I found that the event would not end until eleven o'clock and I would thus have plenty of time to get acquainted with the exhibited works. Usually, I prefer to roam around museums and exhibitions on my own. I do not mind listening to what others are talking about around me, but to begin with I prefer to keep my impressions to myself. Later, however, I can willingly prattle about what I have seen and experienced and do not mind to return in company with others. However, being confronted with works of art for the first time is for me a very personal experience, like meeting someone I have not known before. An intimate encounter, which requires openness, calm and attention, followed by reflection and reflection.

People were crowding the foyer. Most of them belonged to an elite of intellectual, alert and interested young people, who in their quest for originality might end up in some kind of outsider conformism. Everyone was offered a free glass of wine, which was not bad considering the big influx and the fact that it was Prague's municipality which financed the event.

While standing in the midst of the throng, a sense of disappointment got hold of me. To enter the exhibition hall I was asked to put a contribution, "what I found to be reasonable", in a box. Such requests make me ill at ease. What would be “reasonable” for experiencing the works of Prague's young artist elite? Of course, the creations might be quite impressive and thought-provoking, though there was also a risk that it could be pretentious rubbish. Furthermore, the enthusiastic youngsters made me feel lost. I was caught up by a vague feeling of existential anxiety. Who am I? What did I do here?

I felt like a complete outsider, a Swedish old man who did not belong here, in addition I had assumed it was an exhibition of Ai Weiwei's latest art work I was going to see. However, to my relief I discovered that the museum's permanent collection was open for visitors. I hurried over there and found that there was actually a new Ai Weiwei exhibition, Journey's Law, last in a series of diverse events concerning the European refugee crisis, which Ai Weiwei in his characteristically witty, provocative and often quite aesthetic manner previously had presented in Vienna's Belvedere Palace, the Berlin Concert Hall and the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. At each particular event he had presented new objects and activities around the same theme. In preparation for his exhibitions Ai Weiwei had for long periods lived among refugees on the Greek islands, at the Turkish-Syrian and the US-Mexican border areas, where he had collected material and stories, filmed and photographed.

When the Danish Folketing, Parliament, in January 2016 adopted a law which meant that one of the world's richest nations legislated the confiscation of jewellery and valuables exceeding 10, 000 Danish Crowns, i.e. 1, 580 USD, from refugees entering the country, Ai Weiwei immediately closed down his exhibition Ruptures, which at the time was presented in Copenhagen:

”They just want basic human dignity, no bombs, no fear. My moments with refugees in the past months have been intense. I see thousands come daily, children, babies, pregnant women, old ladies, a young boy with one arm. They come with nothing, barefoot, in such cold, they have to walk across the rocky beach. Then you have this news; it made me feel very angry. The way I can protest is that I can withdraw my works from that country. It is very simple, very symbolic – I cannot co-exist, I cannot stand in front of these people, and see these policies. It is a personal act, very simple; an artist trying not just to watch events but to act, and I made this decision spontaneously.”

Even if I had read quite a lot about Ai Weiwei, especially during his much publicized exhibition in Florence, I was completely unprepared for what I was confronted with in Prague. Even if the entrance was free of charge, the visitors were fewer than those attending the other event, probably because that one was a local event, attracting friends and relatives of the exhibitors. I was handed a brochure that thankfully was bilingual and read:

The exhibition Law of the Journey is Ai Weiwei’s multi-layered, epic statement on the human condition: an artist’s expression of empathy and moral concern in the face of continuous, uncontrolled destruction and carnage. Hosted in a building of symbolic historical charge – a former 1928 Trade Fair Palace which in 1939–1941 served as an assembly point for Jews before their deportation to the concentration camp in Terezín – it works as a site-specific parable, a form of (public) speech, carrying a transgressive power of cathartic experience, but also a rhetoric of failure, paradox and resignation.

In spite of the fact that the country's population had been suffering both Nazi terror and Communist oppression, which made several persons flee their country, the Czech government has violently opposed the European Union's refugee quotas. Its prime minister has even threatened to sue the EU because the organization has tried to force the Czech Republic to accept more refugees. The official refugee reception has been extremely modest, between July 2015 and July 2017, the Czech Republic has received 400 Syrian refugees. Nevertheless, or perhaps because of that, Ai Weiwei accepted the National Gallery's invitation for an exhibition. He stated that an important reason for his acceptance was his admiration for the Republic´s former and in 2011 deceased president Vaclav Havel, who he admires as a valiant fighter for freedom of expression and global humanism. In the National Gallery´s brochure, Ai Weiwei declared:

“If we see somebody who has been victimised by war or desperately trying to find a peaceful place, if we don’t accept those people, the real challenge and the real crisis is not of all the people who feel the pain but rather for the people who ignore to recognise it or pretend that it doesn’t exist. That is both a tragedy and a crime. There´s no refugee crisis, but only a human crisis. In dealing with refugees we´ve lost our very basic values.”

In the foyer to the grand hall, which in the 1940s was used as the last gathering place for Jews to be brought to the concentration camp Thersienstadt, where 33,000 died while 88,000 were sent to their death in Auschwitz and Treblinka, was a giant snake undulating just under the roof. On closer inspection it became apparent that it was made out of life vests.

Eight years earlier, Ai Weiwei had made a similar snake out of 3 500 backpacks, symbolizing the schoolchildren who in 2008 died in ill-constructed schools during an earthquake in Sichuan, the year before. The number of children killed had not been announced by the Chinese Government, though Ai Weiwei and his co-workers collected their names and documented their deaths.

Now a similar snake symbolized those who had died during their flight over the Mediterranean Sea. The snake thus became a symbol not only for threat and danger, but also for falsehood, like its alike in the Earthly Paradise, as well as mendacity, movement and change, due to the venom the snake carries, that it can immobilize its victims through its stare and its ability to change skin and become like new.

Two short corridors led into the large central hall. They were wallpapered with black and white, stylized images. Cold, with sharp lines, they depicted war, destruction, refugee camps, dangerous voyages across the sea, risky landings, followed by new camps and deportations.

The picture strips reminded of Babylonian-Assyrian reliefs. Associations confirmed by the fact that they were initiated with images of Greek and Babylonian warriors, followed by modern war scenes with city ruins, helicopters, tanks and robotic fighters.

The scenes were mainly made in profile, as in ancient Egyptian tombs and temple paintings:

Assyrian battle scenes or Persian processions:

The picture bands also reminded of the scenes that wind around Trajan's and Marcus Aurelius´s columns in Rome. The same cold observations of death and cruelty.

The stylization of war and suffering could also be a reminder of how war had been depicted in Chinese propaganda posters. There were no individuals in these pictures, only standard templates of human beings, like documentary films depicting war and suffering through the cool distance of the camera eye.

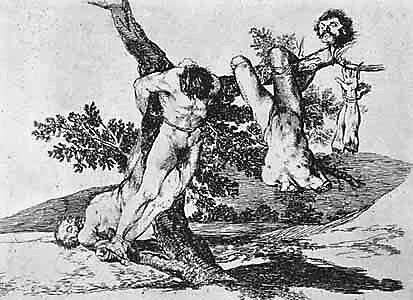

As so much in Ai Weiwei's art, his manner of expression indicated a keen knowledge of aesthetics during different periods of time. It could be just as well Chinese as European art. Ai Weiwei nurtures a great respect for craftsmanship. He knows how war and suffering has been depicted from a distance, of course with a few terrifying exceptions, such as Callot's etchings from the thirty-years war, Goya's furious Desastres de la Guerra and some footage from the war in Vietnam.

Ai Weiwei's refugee tapestry is equally classically balanced, stiff and chilly as John Flaxman's illustrations to the Iliad and the Odyssé, which Ai Weiwei certainly also is familiar with.

After this discreet introduction, the exhibition visitor became overwhelmed by a huge rubber raft, more than seventy feet tall, which with 258 faceless passengers was diagonally hovering over the grand hall.

The raft shaded a marble floor with inscriptions of quotes from famous humanists, who from Mengzi and onwards have been appealing for compassion while pointing to the importance of helping our neighbours.The visitors moved in the shadow of the black raft and its rubber passengers. Its presence, the impact of its shadow could not be avoided. As we moved under it, we trampled upon the words that pleaded for understanding, compassion, assistance and participation.

The black rubber figures, representing nameless refugees, were bigger than we and sat with their backs towards us. In the hall, other rubber figures floated in lifebuoys lifting their hands to gain some attention.

The cool marble floor with its quotes, like the stylized representations on the entrance´s wallpaper, indicated the timelessness and resilience of human suffering, as well as the fact that many of the venerated masters of mankind have been well aware of the state of affairs and been appealing both to our reason and our feelings. Although we live in the shadow of bad conscience and fear, most of us still seem to be unaware of, or hardly bother ourselves about, all the appeals pleading that it would be far better for us all if we shared love and compassion. Instead of preventing our fellow human beings from enjoying equal rights and freedom, instead of nurturing feelings of empathy we are inclined to use violence, while turning our backs to the starvation, suffering and diseases of others.

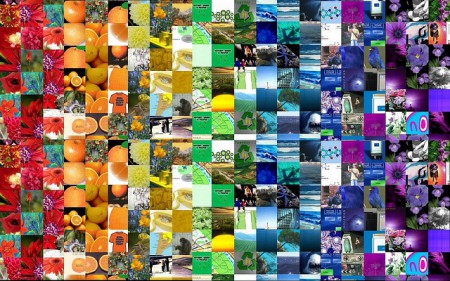

Inside the grand hall, the walls were not wallpapered with aesthetically pleasing drawings, depicting violence and suffering, but instead decorated with thousands of densely arranged colour photographs depicting boat refugees and those lingering in wretched camps around the world.

Their motely diversity constituted an aesthetically pleasing backdrop, looking like the various photomontages that now are fashionable in advertising and some of contemporary art, probably inspired by David Hockney's elegant photomontages, or Chuck Close´s close-ups, which are composed of skilfully arranged, small abstract units.

If you approached the walls, you could distinguish derelict vessels and rafts packed with people, barbed wired refugee camps, people crowding under plastic sheets, in rain and mud.

Amongst some of the walls covered with colour photos, monitors had been installed. They presented videos of a lonely rubber raft in a blue infinity of heaven and sea. These were recordings of Ai Weiwei spending a few days alone in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea. He claimed that he did so in an effort to feel how it could be to be alone in a rubber vessel in the middle of an ocean. That act may undoubtedly seem to be a bit overly theatrical and ridiculous. A well-fed, wealthy and internationally renowned artist could impossibly share the feelings of a malnourished refugee, risking his life while crossing an unknown ocean. However, Ai Weiwei himself agreed that it would be utterly impossible. Through his act he did not try to identify himself with any refugee, instead he explained that he wanted to gain some insight of feelings he might be able to use in his attempts to portray the sufferings of others.

Ai Weiwei´s “prank” angered many of his usual critics, those who had already designated him as a prankster, an ego-tripped joker who veils his clowning within a cloak of self-dramatizing and flashy concern for human beings, while he in reality use his compassionate image to make millions of dollars and gain the admiration of easily duped do-gooders. Ai Weiwei´s adversaries like to point to his “happenings”, like posing nude in Tiananmen Square, or "giving the finger" to a variety of the world's most revered monuments.

Maybe it is like that. Perhaps Ai Weiwei is a crowd-pleasing charlatan, who knows where the wind blows and turns his coat in its direction. Perhaps he is an unpleasant fellow in search of money and fame. I do not know. Nevertheless, to me Ai Weiwei's art does not at all ring false. His work is often quite beautiful and amazing, as well as it arouses thoughts. Is good art ideally not assumed to function like that? Art does not equal truth, it is a comment to the world. An artist does not need to be a perfect human being, it is not s/he who speaks to us but her/his work. Or, as Arthur Koestler allegedly stated: "“To want to meet an author because you like his books is as ridiculous as wanting to meet the goose because you like pâté de foie gras.”

I recently read a book about Picasso, where I found an interview that the Mexican artist, journalist and jack of all trades, Marius de Zaya, conducted with him in Paris in 1923. De Zaya´s course of action was to talk to Picasso during a few days and then in Spanish summarize Picasso´s claims, observations and ideas. de Zaya presented his notes to the artist, who checked them, deleted things he did not like, or found superfluous, as well as he wrote some additions that he assumed would improve the text. de Zaya then translated it all into English and published the text in a US magazine, The Arts, under the heading Picasso Speaks. Among other things, Picasso stated:

We all know that Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth, at least the truth that is given us to understand. The artist must know the manner whereby to convince others of the truthfulness of his lies. If he only shows in his work that he has searched, and re-searched, for the manner to transmit lies, he would never accomplish anything.

According to Picasso, Art is different from truth, in the sense that it is a way to reveal what the artist considers to be a truth, i.e. an interpretation of the reality. Thus, if the message conveys an insight it also makes us consider how the world may be understood, as well as the meaning of our own existence. If art induces such reflections, the artist has succeeded in his intentions. If Ai Weiwei by running around naked on Tiananmen Square or produces giant inflatable rubber boats - and humans, arouse thoughts and fascination he is, according to Picasso's definition, a true artist.

It was not only Prague´s National Gallery's grand hall which exposed Ai Weiwei's work, even the top floor of the big building was filled with his art. There was, for example, a pile of some of the 100 million hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds, painted, glazed and burned by 1,600 craftsmen in Jingdezhen, which for more than a thousand years was the centre of Chinese imperial porcelain production. In 2010, the turbine hall of Tate Modern in London was filled with 150 tons of these seeds.

Other ceramic items at display were 21 Neolithic clay pots dipped in industrial colour:

Hundreds of meticulously crafted river crab in grey and pink porcelain. A Ming Vase painted and glazed on its inside:

Porcelain reproductions of tidal waves and fantastic animals:

A two millennials old pot painted with the Coca Cola logo:

A flower bouquet placed in a plastic basket, with both items made of white porcelain:

Furniture from the Ming Dynasty turned into sculptures and a host of other strange objects, filled hall after the hall. Finally, I reached a room from which I through a glass wall could look down at the huge rubber raft in the grand hall, which then turned out to contain hundreds of children curled up in the middle of the boat and surrounded by the adults. The children were also made of inflated, black rubber.

When I turned around I discovered that the floor of this hall, just like the one in the grand hall below, was filled with text messages. Not made in marble but in modern laminate. The entire floor area was covered with messages from the web, this white noise that constantly surrounds us, day and night. The texts were both fanatical condemnations of the refugee avalanche, day-to-day profane, hateful outbursts, and factual accounts of deaths, suffering, statistics and figures, sensible proposals and desperate disclosures.

On this floor, once again trampled by the visitors' shoes, there were rigorously placed racks with hangers holding a wide variety of garments.

Each rack had a handwritten note informing what it displayed – “children's jeans”, “rompers”, “children's clothes, 0-7 years”, “life jackets, children's sizes, 0-7 years”, etc., etc. These were garments that had been collected on the beaches of Greek Islands. They had been washed and classified according to type and size. There were also lots of shoes and boots, placed in strictly organized rows.

Like hair, glasses and similar things that have been in contact with an individual's body, Ai Weiwei's apparel awoke thoughts about personal lives. A huge accumulation of such things might serve as a reminder of our own, personal lives, as well as the death that constantly threatens us. Seeing all these personal items was in a certain way reminiscent of the shock of being confronted with the piles of clothes, briefcases, glasses and hair in Auschwitz. Items testifying about the inconceivable extent of the brutal, cold-hearted violence that befell their owners.

When I lived in Paris, I sometimes visited the Musée d´Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris not least because the entry was free. In the basement was an installation that impressed me every time I experienced it. The French artist Christian Boltanski had arranged three rather small rooms, calling his installation La Réserve du musée des enfants I et II, The Inventory for Children's Museums 1 and 2.

The installation was from 2000. The walls in the first room are covered with metal shelves on which tightly packed children's clothes have been placed. The room is illuminated by lamps attached to the upper frames of the shelves.

The walls in the second room are covered from floor to ceiling by black and white photographs on anonymous children, each 50 x 30 cm. They are dimly illuminated by lamps placed above each vertical row with four children's portrait. The cords of the lamps hang in front of the pictures.

The walls of the inner room are covered by black bookshelves, filled with telephone directories from all over the world. In the room there is a black table, a bench and a reading lamp. A visitor may pull out a phone directory, sit by the table and find the name she/is searching for.

You enter the first room and immediately associations to Auschwitz occur, though also to your own childhood, your children and parents. The flight of time, the transience of everything, how something that has been familiar, ultimately turns into something strange.

You enter the other room. Associations return to Auschwitz. To the insane slaughter of innocent children. Not only the estimated 1.5 million Jewish children who were massacred in ghettos and extermination camps, but also millions of others who died, mutilated and abused in bombed-out towns and godforsaken hamlets. Who lost all their relatives and forsaken, hungry and frozen wandered around Europe, or in company with their persecuted, terrified parents, without money and possessions, went astray in a world that had lost reason and compassion, without a clue where to turn; blocked, lost and despised. The children in the pictures are anonymous. You do not know who they are, where they come from, though you are confronted with their open, innocent faces.

You enter the third room and become confounded by the contrast between the amount of phone directories from Europe and North America, compared to those from countries in the the Third World. How thin their directories are, even those from gigantic nations like China, India and Nigeria. A reminder of our world's distorted resource allocation. All directories are from 2000. I opened the directory from Kristianstad County and found my birthplace Hässleholm. In the directory Axel and Inga Lundius live at Vinkelvägen 7, though both of my parents are now dead. I find names and phone numbers of class mates and childhood friends, some remain but most of them have moved on to other places, a few of them are now dead. I also find Jan and Rosemary Lundius at Kolonivägen in Bjärnum. I see my family in front of me. Much younger than now. Esmeralda was only eight years. I remember hers and Janna's smiles. Nowadays, phone directories are disappearing, landlines are replaced by smart phones with ever-changing contact possibilities.

Boltanski's three rooms were filled with the weight of things no longer present. They told about the absence of people, the insensitive brusqueness of memories. This despite the fact that traces of children and adults remain in Boltanski´s small rooms; the phone directories, the clothes, the portraits. There I could be confronted with the evil and joys of humankind. The dead and the living, as well as myself, my insignificant person in the midst of this ocean of human life, joy and suffering. My minimal grain of sand in a Sahara of immense eternity. My irrelevance, which nevertheless remains a part of the whole, the Universe.

Ai Weiwei might have visited those rooms as well. For certain, he knows who Christian Boltanski is and his knowledge of the power of things over our minds. The apparel Ai Weiwei and his co-workers collected on the Greek beaches are a similar testimony about other people's sufferings and hopes. Between the garment racks I saw, through the large panoramic window, the big raft with its cargo of black and crouching human figures, throwing its shadow over the great hall below, where once tens of thousands human beings, men, women and children, had been registered for a final destinations where they would be starved to death, shot, gassed and burned.

The drizzle had not abided while I took the tram back home to my daughter and her family. Workers were still welding the tracks, while someone froze in a tent not far from Syria's borders. Someone sat in a derelict boat on a rolling, night-dark sea, with her terrified and wet child in her arms, surrounded by her fellow-travellers' smelly clothes. Somebody lay alone in her bed in an asylum accommodation in a small town in Northern Sweden, waiting for her expulsion to a war-torn country. Somebody reworked his letter to the editor of a local newspaper, lamenting the refugee avalanche threatening his fatherland and all the tax money wasted in support of Muslim fanatics. Another sat by his computer and listed asylum accommodations, hoping that someone else would put them on fire. A politician wondered how to formulate himself to win some crucial votes - for or against the mass immigration? Someone had difficulties falling asleep, being irritated with family and friends who did not realize the threat of uncontrolled immigration, that a stable economy and prosperity were about to be lost forever. Another had difficulty in falling asleep haunted by bad conscience, the notion that he silently was accepting the suffering of others. Somebody was unemployed, suffering from a lousy economy, fearing how tomorrow would be. Some planned an armed robbery. An addict broke into an elderly lady's residence to steal her pension money. Others worked night shift at a hostel for homeless people. In an operating theatre a team struggled to keep a patient alive. Someone watched by a bed where a lonely, old lady was going to die. At the exact moment when I was sitting on the tram, thousands of people died, others came to life and there were people who loved others, being prepared to sacrifice their own lives for that love.

I watched water droplets slide over the tram window, they flashed and shone in the lights of the night.

Crouch David (2016). “Ai Weiwei shuts Danish show in protest at asylum-seeker law” i The Guardian, 27 January. Fajt, Jiří and Adam Budak (2017) Ai Weiwei: Law of the Journey. Prague: Národní galerie v Praze. O´Brian, Patrick (1994) Picasso: A Biography. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.