ARCHITECTS OF A PEOPLE´S HOME: Italian Fascists and Swedish Social Democrats

Sometime in the 1990s, I rented a room at the Swedish Institute in Rome, located on the outskirts of Villa Borghese, Rome's central park with pruned pine trees, palaces, fake temples, a zoological garden, fountains and ponds. The Institute is housed in a magnificent building of red brick and white travertine, its halls and rooms are bright, with high ceilings and large, oblong window. It was furnished by the time´s leading Swedish designers and artists. The edifice was created by Ivar Tengbom, whose masterpieces include Stockholm´s Concert Hall. Tengbom was the main representative of a style that in the UK and the US was named "Swedish Grace”.

The Institute´s enclosed courtyard features a fountain; the graceful and speedy Sun Glitter, depicting a naiad riding on a dolphin. It was made by the Swedish sculptor Carl Milles who at the time was at the height of his international fame. It might be assumed that Tengbom chose the sculpture to adorn his building, especially considering how impressed he had been by Milles´ Orpheus Fountain, which was placed in front of the Concert Hall colonnade. However, it was Olga Milles who in 1956 donated the sculpture to the Institute, a year after her husband's death.

I had a pleasant stay at the Institute; the staff was accommodating and professional. In the evenings the young researchers gathered for social events - art historians, archaeologists, architects, writers and musicians. Among others I acquainted a nice lady named Eva Nodin, who was writing her PhD thesis on Fascist architecture and children's summer camps. My conversations with her made me ponder about the Swedish Institute; its architecture and the Social Democratic welfare state. The lavish Institute had been built between 1937 and 1940, a crucial period that gave rise to the Swedish society I now live in.

According to Eva Nodin there were similarities between the Swedish Social Democratic welfare state idea and Italian Fascism. I thought about what she said while I wandered around in the beautiful building, or watched Milles´ fountain. Previously, I knew that the sculptor had been supportive of both Hitler and Mussolini, and wrote that he appreciated the "order" they had created in Europe: "I love people who clean up their homes, keeping them nice and tidy for the Sunday gatherings. I do not care what you call them, but I hate disorder."

It is possible that Eva Nodin went around with thoughts similar to mine. I have not seen her since my stay at the Swedish Institute, but I know that after she published her thesis she wrote a book about Carl Milles' political convictions and the relationship between art and ideology. I have not read her In the Kingdom of Thousand Opportunities, but know it deals with Milles infatuation with National Socialism and Fascism, his thoughts about war and peace, life, death and resurrection, all issues that were current in Europe between the wars and where clashes between left- and right-wing forces quite often turned into open violence. Nevertheless, German National Socialists, Italian Fascists and Soviet Communists claimed they were approaching an utopia of peace and order within their respective nations and Swedish Social Democrats strived hard to realize what they dreamed to be a Folkhem, “a People´s Home”, where all social classes coincided in an effort to build a modern, effective and fair society.

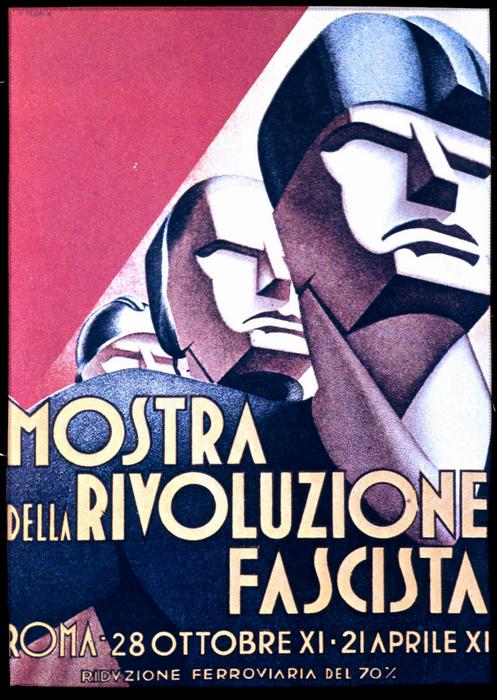

After Mussolini's accession to power in 1922, Swedish writers and artists continued to visit Fascist Italy, just as enthusiastically as before. Several of them did, just as many Social Democrats, depict the social changes of Italy in a positive manner and noted that Fascists supported modernist art and architecture, as well as they launched seemingly comprehensive projects to improve public health. On the official, political level, however, there was some animosity between Italian fascists and Swedish Social Democrats, especially since the influential Social Democratic leader Hjalmar Branting in 1924 had warned Europeans for Italy's colonial ambitions, as well as he officially declared that the assassination of the Italian socialist leader Matteotti had been arranged by Mussolini. Sweden was the only nation that advised against Italy acting as host to the League of Nations Council meeting the same year.

Nevertheless, the somewhat strained relations did not prevent the Italian Ambassador to Sweden from in his communiqués, which were read by Mussolini with great interest, constantly repeat that the Swedish social policies appeared to be "a direct replication" of Fascist programs. Ambassador Gaetano Paternó quoted his conversations with leading Swedish Social Democrats like Ernst Wigforss and Rickard Sandler, where he stated that they agreed with him that their party's policies were similar to the Fascists in the sense that they were characterized by a high degree of pragmatism, which made it possible to ignore "old party ideologies."

Paternó wrote that when he during a private conversation with Per Albin Hansson, the Swedish Social Democratic Prime Minister, had mentioned to the socialist leader: "that the measures announced in his program had a fascist character, he looked me in the eyes and replied: 'And why not? '".

Were there similarities between the two ideologies? The 1932 election initiated an era of Social Democratic dominance which consisted right up until 1976. In 1936, a Social Democratic party congress was convened in Stockholm. It was a summing up of the situation created by the Socialist government's successes, the handling of the economic crisis mitigation and the international deterioration of democratic values. It was during that congress that the Social Democratic forces finally were consolidated and guidelines for a future welfare state were established.

By that time, however, the Swedish-Italian relations had cooled down considerably. A year and a half before the foundation stone was laid to Tengbom´s impressive building, Italian combat planes had bombed the Swedish Red Cross field hospital in Abyssinia. More than sixty local employees and a Swedish medical worker had been killed, and the Swedish head physician had been seriously wounded. Swedes were outraged. Nevertheless, it took only a few years before a trade agreement was signed between Sweden and Italy. During the Second World, Sweden distributed Italian attack aircraft and a vast amount of other Italian produced military equipment to Finland. No less than 84 Caproni CA 313, an Italian bomb - and reconnaissance aircraft, were purchased by the Swedish Air Force.

While I lived at the Swedish Institute, I found some documents in the library, which revealed that even before the new building had been erected the Institute had been visited by a large number of influential Swedish architects. Many of them later joined the functionalist movement, which in Sweden was supported by many young and socio-politically interested architects. They came to have a great influence on the profound social changes that the 1940's and 1950's brought to Sweden.

They had visited an Italy characterized by a Fascist ideology, which the movement´s most influential theorist, Giovanni Gentile, described as a third way between a liberal-capitalist stance and Marxism. Fascism proclaimed that the state had to be dominated by a single party. With the support of corporate organizations, the State would manage the whole of society, while it at the same time protected private property. To make this possible, national unity under a strong and effective management was an irrefutable requirement. A new collective consciousness had to be created and bolstered.

Mussolini abhorred what he believed to be the outside world´s notion of the Italian as a sycophantic, mandolin playing sybarite. That despicable image had to be obliterated and replaced by the notion of a steel hard, sound and feared Italian elite of supermen, hence the Fascist concern for molding the rising generation; children's summer camps, sports facilities and public hygiene. Concepts such as italianita, italianess and romanità, Roman virtues, had be filled with a meaning, an urge which unfortunately also led to violence and intolerance, the build-up of a community focused on war preparations whose representatives became guilty of wanton abuse of colonized populations in Libya and Abyssinia. Fascism was hostile to ethnic- religious- and any other groups, and/or individuals, who could not be assimilated with the nation, or even refused to participate in the grandiose schemes of the Fascists.

What Fascism attempted to achieve was a totalitarian, social engineering, where legislation, taxation, social policy, planning and education would transform society. After World War I, it was common among several European leaders to perceive a thorough ”modernization" of the entire society as that the best solution to social problems. Social Democracy, Bolshevism, Nazism and Fascism all pursued enhanced civic control. The difference was mainly in the methods - democracy or totalitarian violence. By his ascension to power, the anti-Communist Mussolini declared:

We still have a long way to go before we have appropriated the Russian system. But in any event, Fascism will follow the example given by Russia. You can be sure of it, all you Italian crooks and socialists. Whoever betrays us will perish.

Italian Fascism differed from Soviet Communism by its stated commitment to corporativism, an ideological orientation that was presented as a middle ground between socialism and free capitalism. Economic differences were regarded as a natural condition, as well as differences in material living conditions. The aim of the State was not to seek to equalize class differences, but to ensure its right to govern society in such a way that neither the Nation´s nor the State's welfare and efficiency were compromised by the self-interest of different groups.

This kind of thinking had already been launched by the Vatican, which based its views on Paul's first letter to the Corinthians, where he writes:

But now hath God set the members every one of them in the body, as it hath pleased him. And if they were all one member, where were the body? But now are they many members, yet but one body. And the eye cannot say unto the hand, I have no need of thee: nor again the head to the feet, I have no need of you.

and

Now ye are the body of Christ, and members in particular. And God hath set some in the church, first apostles, secondarily prophets, thirdly teachers, after that miracles, then gifts of healings, helps, governments, diversities of tongues. Are all apostles? Are all prophets? Are all teachers? Are all workers of miracles? Have all the gifts of healing? Do all speak with tongues? Do all interpret?

Accordingly, the official Catholic opinion was that society ought to function like a body where every individual served an integral part of social, economic, occupational, ethnic, national and family-based associations.

However, Fascism changed this view by pointing out that in modern industrial society was no longer expressed as identical with an individual´s personality, as if frozen within a societal role. Fascism proclaimed change and mobility. According to Fascist ideologues, identity was rather manifested in behavior, attitudes, speech and style - in other words by cultural characteristics. Industrial society demanded large and tightly organized political entities, which demanded to be ruled by a firm hand, i.e. by a dictatorial system. Nevertheless, such views did not mean that the corporative notion of society as a body was discharged.

This "body image" led to the perception of “social diseases”. Illness and weakness were primarily regarded as societally determined; they were mainly due to a poor environment, lack of knowledge about basic rules concerning hygiene, to poverty and lack of food. The remedy was to provide comprehensive community planning that could promote a healthy lifestyle among all citizens.

Cultural standardization and national socialization would be achieved through an effective education system, while modernist architecture would create a healthy living environment. The health aspect came to permeate Fascist society, where purity also ranged outside the body and was given a moral and spiritual aspect as well, whereby it came to include art and architecture.

For modernist architects a building's “purity” was not always primarily motivated by functional reasons, but also seen as a moral position where purity became an end in itself.

Fascist Italy benefited the arts through its pursuit of an aesthetically pleasing package that fused ancient ideals with avant-gardist innovation. Mussolini was personally quite uninterested in art and state support to artistic endeavors was consciously divided between different groups of artists. It was generally not required that art should follow the party line. At the opening of the trend-setting art exhibition Novecento in 1923, a year after the Fascist takeover, organized by Mussolini´s influential mistress Margherita Scarfatti, the aspiring dictator declared that:

It is far from my idea to encourage something similar to a State art. Art is created within the individual domain. The State has only one duty: Not to undermine the arts, but to create humane conditions for the artists and thus encourage them to apply a national point of view in their creation of art.

Such declarations did not hinder the Fascists from preaching that "a new, vigorous Fascist mankind" would break free from the snares of antiquated traditions, words and thoughts. Fascism would "make history"; human creativity would be attending to the production of needful items and social services. Artists would not create art for art's sake, but contribute to the creation of a new culture, stimulating the "total force and power to act and change".

Fascists were talking about a historical unification of labor and capital. The question is whether that goal was ever achieved in Italy, but many have argued that the so-called "Swedish model" was on track to achieve it; supported by state-run health reforms and community-altering energies, architecture and urban design were turned into privileged instruments for the creation of a new mentality. Everything would be addressed through detailed planning, based on sound scientific approaches. A new type of urban design was created on the basis of accurate topographical and social studies, so-called “neighborhood planning”. Residential complexes would be planned around the needs of citizens and complemented with shops, schools and various community facilities. An approach that already had been tested in several Italian cities.

Both in Fascist Italy and Social Democratic Sweden, it was assumed that development should be enforced by the State and that private interests would ideally be subordinated the public good, something that was more efficiently achieved in Sweden than in Italy. State control was a general European trend within many intellectual circles. According to the CIAM (Congrès Intrenationaux d´Archtecture Moderne), a pan-European association of architects formed in Athens in 1928, state control was the prerequisite for modern, functional architecture:

Each and every town planning programme must be based on careful investigations carried out by specialists. It must anticipate every stage of urban development, both in time and space. It must coordinate the natural, sociological, economic and cultural factors which are present in each particular case.

Ideally should all urban planning and architecture meet four basic functions; housing, recreation, work and transportation. All social thinking should be firmly based on science´s ability to promote the good life, particularly through an emphasis on light, air and greenery. Perception of space should be based on an “opening up of the room”. As in a poem written in 1951 by the Swedish poet Ragnar Thoursie:

Above time´s rustling in pine trees, above the flight of ridges.

Steers from night to day, from want

To freedom, an urge

Which is the same for all of us. An open city,

Not even fortified, that we build together.

Its light strikes up towards the emptiness of space.

One of the promoters of CIAM, as well as one of Modernism's great gurus, was the Swiss Le Corbusier (pseudonym for Charles-Edouard Jeanneret), who in 1923 in his revolutionary manifesto Vers une architecture, Towards an Architecture, wrote:

A house is a machine for living. Baths, sun, hot-water, cold-water, warmth at will, conservation of food, hygiene, beauty in the sense of good proportion. An armchair is a machine for sitting in and so on.

Le Corbusier described with disgust all those botched buildings that littered the entire European continent; decaying, outdated dwellings enclosing a suffering mankind, like rotting snail shells, stale, useless and unproductive. An anomaly, residue surviving among clean, efficient industrial complexes, in which modern people occupied themselves with producing a better future for all of us. According to Le Corbusier the craftsmanship of ancient farming communities has become obsolete, while prolific connections between factory environments, banks and offices are becoming ever more efficient and healthier. However, the wretched milieus in which the majority of the workforce is forced to live in are "tuberculous" dwellings whose residents' are becoming “demoralized within an anachronism".

Every citizen feels the need of sun, warmth, clean air and polished floors. We want to dress comfortably, carry clean clothes and sleep on white, ironed linen. We are all in need of an environment allowing us to relax and gather strength after the daily toil and bustle. Our muscles and brains cannot any longer be trapped and tormented by unhealthy dwellings.

Although Le Corbusier's political views were entrenched in French conservatism he was constantly on the lookout for government authorities willing to grant him a free hand to realize his advanced ideas. Le Corubuiser appealed more to logic than politics when he wrote that: "Once his [the scientific planner´s] calculations are finished, he is in a position to say – and he does say: It shall be thus!”

Le Corbusier repeatedly sought out Russian Bolsheviks and Italian Fascists, not because of his political persuasion, but in the hope that totalitarian states would help him fulfill his visionary plans. Below we see Le Corbusier next to Ivar Tengbom (right), the Swedish Institute's architect.

In 1925 one of the most influential ideologues of Swedish modern architecture, Uno Åhrén, returned home from the World Exhibition in Paris. He was euphoric and the reason for his enthusiasm was that he had experienced the exhibition's most acclaimed work - a villa named L'esprit Nouveau (see above), which had been designed by Le Corbusier. Åhrén wrote:

A longing for air, space, for freedom got hold of me. What a grateful thought I directed towards the one who was merely doing his job, without caring about looks ... an act resulting in purity of form, performance simply became adapted to function, ignoring the arts.

Together with other Swedish architects, artists and designers Uno Åhrén considered that the aesthetic revolution they advocated was intimately connected with a social one - the dream of a new society and of a new man. Art became politics. Åhrén wrote about his Parisian experience: "After this, the air at home feels even more oppressive. Why is everything so locked up here in Sweden?" However, soon he found himself in the throes of change. In 1943 Åhrén became head of Svenska Riksbyggen, the Cooperative Building Organization of the Swedish Trade Unions, and until 1963 he was professor of urban planning at KTH, the Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden´s first polytechnic and main provider of Sweden´s technical research and engineering education.

In a book published in 1943, Architecture and Democracy, Åhrén suggested that modernist architecture in cooperation with Social Democracy would transform Swedish society:

The representatives of the art of building now find themselves in the midst of politics. The world is being remade. We are all involved. However, we must never give up the basic principles of democracy and human rights.

A People's Home was being created. The People´s Home was for many years a mighty catch-word among Swedish Social Democrats. That I recently came to think about my time at the Swedish Institute in Rome was triggered by the fact that I read how the Social Democratic Prime Minister Stefan Löfvén had characterized the Sweden Democrats as "a small neo-fascist party that believe they will have a decisive influence and set the agenda for Swedish politics." Around the same time I read Jimmie Åkesson´s (leader of the xenophobic and constantly growing Swedish Democratic Party) unusually boring "autobiography" Satis Polito and his strange prank to provide his book with a "Foreword by Albin Hansson". The highly influential Social Democrat Per Albin had in 1928 re-introduced the concept of a People´s Home in Swedish politics. Jimmie Åkesson inserted a ridiculous disclaimer for placing fictitious opinions in the mouth of this “father” of the Swedish People´s Home concept, by pointing out that:

The following is obviously not written by Per Albin Hansson. Indeed, it has been nearly seventy years since the then Swedish prime minister at Ålstensgatan stepped out of the tram of Line 12, fell to the ground and died. This preface is thus fictitious, written from the outset of what the author believes that Per Albin would have expressed if he had had the opportunity to do so.

Personally, I assume it to be highly improbably that a well-spoken politician like Per Albin Hansson could have been able to express himself with such awkward phrases as those that Jimmie Åkesson make him utter, like: "I cannot easily let go of a feeling that the Party's foundations and ideals are being dragged by the nose." I cannot easily let go of a feeling of being tortured by Jimmie´s almost unbearably attempts to apply an archaic language in his ludicrous attempts to imitate Per Albin´s perfectionist parlance. Poor Jimmie makes one cockup after the other, while he makes Per Albin utter thoughts improbable for a man of his persuasion, making statements in support of a political party that is far removed from this Social Democrat´s pragmatic and democratic stance: "I have no understanding of the [Social Democratic] protagonists of what I have understood is called multiculturalism. However, I would have loved to be there and appealed to them to think one more round." Think one more round? Well, Jimmie makes his fictional Per Albin Hansson state that the Sweden Democratic Party with its "social conservatism" has "picked up what my party has lost, or simply thrown away”. An amazing usurpation and misuse of a long dead, fervent Social Democrat.

The Sweden Democrats' imaginary People´s Home might possibly be an idyllic, rural Sweden, with red cottages and strapping, blonde farmers. Such a place it is at least conjured up in many of the party´s election posters. At least does the party secretary Björn Söder seem to have something like this in mind when he has inspired his party to distribute Astrid Lindgren's fairy tale books for free. Söder has stated that the world famous, and in Sweden venerated, storyteller often depicts his dream of a People´s Home and he wonders what this “community-minded” writer, with her "big heart", would say if she got to see how Swedish society has evolved after her death. “Where young immigrants who, unlike Emil of Lönneberga´s innocent pranks, are throwing stones at fire fighters and the police just for fun while they burn up buildings and cars in the suburbs?"

The Sweden Democrats budget proposal of 2014 included a text entitled The Story of Sweden. It was markedly different from the description given in the budget proposal the party presented in 2005, where instead of writing about the glories of the nineteen hundred thirties when foundations for the People´s Home were laid it talked about the olden days when Swedish specificities emerged "out of the flocks of hunters and gatherers, who after the melting of the mighty ice sheets eventually took the Scandinavian Peninsula in possession." Now the Sweden Democrats played a completely different tune and began their depiction of Swedish history somewhat later, namely in 1809, when Sweden after the Finnish War, lost a great part of its empire and ended up as "a poor nation, badly damaged by war." However, in spite of all odds, Sweden would rise from the ashes and "today, we compete in fields as diverse as aerospace, nuclear physics, information technology and biomedicine." How could all this happen? Well:

Sweden was, to sum up, uneducated and poor, but Swedes are obsessed with shared values. Nordic Lutheran work ethics and norms of consensus and teamwork were central to us. An institution is not necessarily something that is easy to establish, through laws and authority. An institution is not necessarily even aware of its own existence. An institution may equal implicit attitudes between people, for example, being able to show consideration for fellow beings, or it may take the form of values, such as being diligent and industrious. Common cultural values guarantee a strong respect for formal institutions – for our common laws.

To return to Björn Söder´s rhetoric question - what would Astrid Lindgren say about all that? Obviously she would not think we ought to throw out immigrants, given that Ilon Wikland, who made the praised illustrations for most of her books, was a refugee from Estonia and Georg Riedel, who put music to her songs, was a refugee from Czechoslovakia.

Astrid Lindgren has posthumously reacted to Jimmie Åkesson´s and Björn Söder´s pathetic attempts to enroll her in their party. When one of her German pen pals became annoyed at how Astrid in her book Rasmus, Pontus and Toker had let an unsympathetic, petty criminal and sword-swallower called Alfredo speak in what in Sweden is called circus-German and furthermore hinted that he might have been a gipsy, she replied indignantly that:

It was hard and bitter for me to read your words, for someone who detests all nationalism as fervently as I do. I thought you knew that. I thought you knew that I dislike any kind classification of human beings, to divide them according to nations and races, all kinds of discrimination between whites and blacks, between Aryans and Jews, between Turks and Swedes, between men and women. Ever since I was big enough to think independently, I have resented the blue and yellow [i.e. the colours of the flag] grand Patriotic-Swedish [...] it seems to me as abominable as Hitler's German nationalism. I have never been a patriot. We are all humans - this has been my particular passion in life. And because of this it is that your words hurt more than I can say, that you have read such things out of my Rasmus manuscript, where I tried to convey something completely different.

But – in spite of it all - maybe was Astrid Lindgren, like so many of us Swedes, unwittingly able to expose ignorance and unconscious hostility towards things foreign to us.

In their budget proposal Jimmie Åkesson and the Sweden Democrats continue with their tale of Swedish history. They state that it was the Swedish Social Democrats who in the thirties introduced and supported the so called Saltsjöbaden Agreement, a labor market treatment between the Swedish Trade Union Confederation and the Swedish Employers Association, which meant that the two sides should avoid open conflicts and conclude agreements without interference by government. A pragmatic approach which, according to the Sweden Democrats created future wealth and made "the State a redundant operator" (to me it is somewhat unclear what they mean by that). After a few years, still according to the Sweden Democrats, the path towards a brighter future darkened considerably:

After a completely incomparable recovery from the tragic loss against the Russians in the Finnish War of 1809 many Swedes realized that this time the threat did not come from the outside; it consisted of gruesomely unsuspecting politicians, who raised on pedestals had distanced themselves far from ordinary people's reality. Under the Bill 1975: 26 on Guidelines for Immigrant and Minority Policies the government of Olof Palme proclaimed that Sweden should no longer be a Swedish nation, but a multicultural one - "Immigrants and minorities should be given the opportunity to choose how far they want to be part of a Swedish cultural identity, or to maintain and develop their own original identity ".

Nowadays, the once glorious Swedish nation finds itself in a free fall further down into the nation dissolving hell of multiculturalism, the terrifying demon of Sweden Democrats. Salvation from this cataclysm can only be found through the Sweden Democratic party, which wants to protect values that apparently were brought to Scandinavia by flocks of hunters and gatherers that arrived in Scandinavia during the last glaciation, at least 50 000 years ago. I assume these harbingers of values and culture were Neanderthals and cannot help failing to understand what they could have had in common with the Swedes of today.

On the cover of his book Satis Polito (a phrase which according to Åkesson means “sufficiently polished”, though someone more familiar with Latin would probably translate it as "enough for the polished”). On the cover, Jimmie Åkesson sits on a couch under a few Social Democratic election posters from the thirties, apparently placed there with the help of photo shop. A more appropriate cover would probably be Jimmie sitting in the position of the Fascist admiring Carl Milles´ huge, monumental statue of Gustav Vasa - the dictatorial ruler of a “united” Sweden during the sixteenth century – placed in the entrance hall of Stockholm´s Nordic Museum, under whose effigy, made of robust Swedish oak, we can read the motto Waren Swenske, Remain Swedish. Though such an image would probably not be sufficiently mainstream, so on the cover the leader of the Sweden Democrats sits and talks with a photo shopped cat instead.

Let us return to The People´s Home. The First World War made Europeans realize the immense importance of engineers and planners. After experiencing what could be accomplished when the war effort demanded a total mobilization, politicians and technicians began to imagine what could be achieved if corresponding energy and planning were put into the construction and accomplishment of general welfare, rather than mass destruction. Within Bolshevism and Fascism the engineers/constructors became heroes, men who would change the world.

In his novel The Naked Year, the Bolshevik author Boris Pilnyak wrote in 1920 that the world would be cleansed by the cathartic violence of the Bolsheviks, engineers with “tanned figures, in tanned leather jackets”. According to Pilnyak the revolution was an orgiastic climax, “smelling of genitals”, during which the onward sweeping spiritual and technical advancements of “Asiatic Asia” would save and change the decadent West. Thoughts mirrored by the influential German philosopher Oswald Spengler, who in the same year as Pilnyak in his Prussiandom and Socialism, while arguing for an “organic, nationalist brand of socialism and authoritarianism” predicted that human society would reach its pinnacle “not in the United States, not even in Japan, but in Soviet Russia”.

Change was the motto for almost anything. Time obtained an intrinsic value, it would determine our existence. Ambition and action would inspire people to change human existence into something, brighter. Dazzling technological inventions would relieve us from soul killing work and boredom. We had to “join time”, unite with the pulse of life. By constantly working with new solutions, we would turn into servants of tomorrow. Already in 1912, Swedish Social Democrats had founded their own publishing house Tiden, The Time, to publish books for the advancement of the knowledge and influence of the working classes.

Tiden´s first director was Gustav Möller and the board included Hjalmar Branting and Per Albin Hansson. Hjalmar Branting was the son of a well-known university professor, while Gustav Möller and Per Albin Hansson came from humble beginnings, having worked as journalists. In particular, Gustav Möller had amassed an impressive knowledge of Marxist literature and developments within the European labor movement. He was considered as the party's leading ideologue and was like Per Albin a typical careerist, albeit with a strong ideological motivation. It was Möller, who in his later role as minister for social welfare came to be intimately associated with the extensive social reforms that were implemented by the Social Democrats. Möller regarded social policies as central for the transformation of the capitalist social order in a socialist direction and said that all welfare policies must operate in accordance with a well thought out and comprehensive strategy.

Within the party, it was apparently popular to compare Möller and Per Albin Hansson, a commonplace opinion was that Möller was endowed with the better intelligence, while Per Albin had the stronger will. Möller socialized with the party's intellectual elite and many younger politicians regarded him as role model and mentor. He saw himself as an intellectual and constantly advocated the importance of acquiring education and knowledge, something he especially demonstrated through his close and enduring association with Tiden´s publishing house.

The party line emphasized the utmost importance for workers and peasants to acquire education, to become as knowledgeable and erudite as their political opponents, something which led to the founding of public educational institutions and colleges, but also to a great reverence for scientific expertise and "academics".

After the First World War it was necessary to look to the future with optimism, not least among young socialists. Many of them preached the importance of being “united with time and change”. By embracing constant action and unbridled creativity they intended to create such a perfect society as possible. Like when Karin Boye, a lady contemporary with the century, in 1927 became a member of the socialist journal Clarté´s editorial board and wrote her poem In Motion:

The best day is a day of thirst.

Yes, there is goal and meaning in our path -

but it´s the way that is the labour´s worth.

The best goal is a night-long rest,

fire lit, and bread broken in haste.

In places where one sleep but once,

sleep is secure, dreams full of songs.

Strike camp, strike camp! The new day shows its light.

Our great adventure has no end in sight.

During the parliament´s preliminary debate of 1928, the Social Democratic group leader Per Albin Hansson introduced the concept of The People´s Home in socialist rhetoric. By being both a national program and a socialist utopia the notion captured the zeitgeist. It represented what was perceived as traditional values, at the same as it set up stimulating tasks for the future – a cohesive community based on equality would create a new society inspired by the best of Swedish traditional values concerning morality, common duties and job satisfaction. A vision of the future that calmed the bourgeoisie and disarmed the radical left.

Per Albin's political outlook was characterized by a sense of strong optimism: "Working together in harmony with solid development goals is likely to give us the confidence needed to build a fair and just society." A development that hopefully would harmonize all societal interests and ideologies. Sustainable social development would not only bring a higher material standard of living, but also an increased societal rationality. Revolution and totalitarianism would at all costs be averted. For Per Albin Hansson democracy was the guiding principle above all others, but it was a form of democracy that would be secured through cultural standardization and national socialization based on an effective school system equal for all combined with an inclusive, decent standard of living.

Since the party's founding in 1889 had the Swedish Social Democratic Party considered socialization, i.e. the transfer of private property to the public sphere, as one of its main objectives. After the 1926, when the Social Democratic Party ended up outside of the government for six years, totalitarian forces in nations like Germany, the Soviet Union and Italy grew increasingly powerful and began to threaten social peace even in Sweden, at the same time the Great Depression was crippling the economy. During the harsh winter of 1932/33 more than 200 000 able-bodied Swedes were unemployed, particularly families with children were badly affected, One third of the children were estimated to be malnourished. The birth rate fell sharply and became the lowest in the Western world. Overcrowding was tremendous and housing substandard.

In the 1932 elections the Social Democrats gained over 40 percent of the votes and were able to form a minority government. In order to pass a radical program for combating unemployment the party had to make an agreement with the more conservative Agrarian Party and accordingly toned down its socialization plans, while propagating a comprehensive consensus policy. In Per Albin Hansson´s words:

This means that socialization becomes what it should be, not an inescapable principle, but an option to choose, or avoid if that is deemed to be necessary. All depending on if a socialized production is taking us closer to, or if it is distancing us from, the material and spiritual welfare and freedom we are trying to obtain, something which is our real target.

"Material and spiritual freedom" in support of democracy and prosperity was something that the country's young, radical architects also professed. Through the great Stockholm Exhibition of 1930 the general public was introduced to functionalistic, revolutionary design and plans for a radical change in society. In connection with this display of modernism, five activist architects and an art historian met at the City Hotel in Vaxholm, a fashionable island in the Stockholm archipelago, and during one week they discussed and compiled a manifesto about architecture's future role in society. The result was a remarkable text: acceptera, accept.

The book is filled with illustrations and has a startling typography. It has more than two hundred pages, but looks like a weekly magazine. Both layout and language are modern, liberated from the increasingly archaic inflections that still were in use at the time. Nevertheless, to a modern reader the publication does give a somewhat superannuated impression. Its pedagogical tone reminds me of my early school days when dusty curtains were drawn and a 16-millimeter film projector began to rattle in the classroom. From the loudspeakers came the voice of a pompous narrator who briskly explained "young boys learning responsibilities", "how ax becomes a loaf of bread", "how iron ore becomes steel", or what life was like in a Stone Age village, a film where we could glimpse the marks of smallpox vaccinations on the upper arms of the supposedly Nilotic foretfathers. Everything was presented in a clear and unwavering manner, free from any kind of doubt, just as in the book acceptera.

The publication contains cryptic digressions and occsasional dialogues between "we", "the form traditionalist" or "a gentleman", something that makes the whole thing quite enjoyable and often startling reading. The manifesto concludes with a number of short sentences, such as: "We have no need of an ancient culture's outgrown forms to sustain our self-respect. We cannot sneak out of our own time backwards. Anyone who does not want to accept refrains from personal and social development. He will subside within a meaningless pose of bitter heroism, or unworldly skepticism."

According to the authors, traditional Swedish taste had lagged behind, putting our entire society at risk of becoming hopelessly outdated, impractical and unhealthy. "Living standards have not followed the speed of social and production changes". Swedish social life was characterized by fragmentation; work, home life, parenting, education, recreation, religion, social affairs - all such notions and activities were antiquated and could be found at different stages of development. It was high time to start planning for the future, to build a bridge from the past to the ideal society of the future. Optimism seems to be limitless. acceptera wants to liberate Sweden from its "burden of history". According to the authors, functionalism does not constitute a temporary change in taste, but implicates an entirely new way of thinking - a process of liberation, "as revolutionary as when science was separated from religion."

One chapter is devoted to "cosiness" and the authors concluded that the basis for being snug at home is the practical organization of a household.

The comfort that every normal person aspires to is intimately connected with what is practical and aesthetically pleasing, things that are functional and activities that are well organized. Each thing in its place and easily accessible, fair and appropriate lighting, both natural and artificial, available sunlight, peace and privacy for both resting- and workplaces, comfortable furniture and good furnishing possibilities.

The things we surround ourselves have to serve us well. We should attach ourselves to things that are both beautiful and functional. Unnecessary ornaments and anachronistic knick-knacks are useless burden. All tools and adornments should be neat, unadulterated and if possible practical. However, we should be allowed to add an occasional detail whereby we could "personalize" prefabricated things. Everyone is of course free to mix styles and tastes, but from now on everything that is produced for public consumption ought to be functional and aesthetically pleasing.

acceptera describes what it calls an A-Europe and a B-Europe, where A-Europe is like one, big organism, where everything is at once specialized and organized, where each "cell" - from the family farm to the large factory, or the bank, is dependent on each other. An organic entity that manifests itself also in an individual woman´s and man´s appearance and behavior. However, B Europe is a backward place, with few and bad roads. A place where the farmers themselves build their huts and farms, eat their own seed and animals. They produce little and what they buy come from either the village blacksmith, the village carpenter, or from the market they may visit once or twice a year. They write rarely or never, and if they receive any mail it probably comes from a relative who has left misery behind and migrated. The peasants´ horizon lies at the limits of their village. The State makes itself felt through tax levies and enforced military service. Ideas are exchanged as rarely as social services.

According to accept it was high time for Sweden to leave B-Europe behind and turn into one of A-Europe´s frontrunners. The authors of accept were all convinced socialists and generally fierce opponents to both Nazism and Fascism, as well as Soviet Bolshevism. They considered themselves to be not only architects, but also radical economists and sociologists, the shock troops of a new and just society. However, there was also some danger inherent in the kind of social engineering they pleaded for.

As an example, Francis Dalaisi - the French economist who had inspired the authors of acceptera to write about A and B Europe - completely lost his track and ended up in the wilderness of Nazism and anti-Semitism. The initially left leaning Dalaisi had argued that the contradictions of modern world could be overcome if a global society was created on the basis of an international consciousness that accepted the equal worth of each single individual. A conscience that would emerge from economic dependence and the increasingly intricate communication networks that were changing contemporary Europe. National borders would become obsolete and people would come closer together. Dalasai warned that without international solidarity, social and political tensions would increase until Europe had fragmented further into ever decreasing nation-states, which inexorably would topple in war and chaos. Dalasai ended up as a Nazi collaborator within an occupied Paris, where he devoted himself to writing anti-Semitic pamphlets and pay homage to the Nazi regime as the only political force which could realize his dream of a united Europe.

Many politicians, architects sociologists were, in spite of their strong social pathos, members of wealthy and privileged classes. When I read their texts, I sometimes - despite my admiration for their efforts – become overwhelmed by uneasiness. It cannot be denied that several of the Swedish reformers obtained extraordinary powers and quite a high degree of narcissism. They had a strong passion for social justice, praiseworthy insights and were often outraged when confronted with abuse of power and social distress. However, their elevated positions made several of them blind to some of the problems that arose as a result of their social engineering and despite their evident professionalism there were within their motivations and actions elements of personal prestige and gain.

Many politicians and authorities identified themselves with their specific tasks, a tunnel vision that occasionally might have limit their horizons and for example made them forget the consequences of their actions might have for certain groups and individuals. The Social Democratic economist and politician Ernst Wigforss wrote in his memoirs that Per Albin Hansson´s popularity within the party depended less on his ability to attract personal sympathies, than on his feeling that he instinctively belonged to the movement in which he had grown up. Personal power interests and desire for the success of the party had in Per Albin's person mixed into an indissoluble union.

The not so pleasant attitudes inherent in some of the ideologies around the notion of a People´s Home is something I intend to touch upon in my next blog post. In the meantimeI quote the great Swedish poet Gunnar Ekelöf´s poem from 1945. The title Till de folkhemske, is a wordplay. The English word “home” is hem in Swedish. The attribute hemsk could thus, according to Swedish language rules, equal the English “homely”, but as a matter of fact it means “terrible”. Consequently does de folkhemske not mean “the homely people”, but “the terrible people”. Till de folkhemske does thus mean To the Terrible People, at the same time as it hints at the concept Folkhem, People´s Home.

For the sake of aesthetic demands

(which also are practical reasons),

the architects have turned the clouds into squares.

Suburbs have grown above forsaken forests.

High above the ridges, cloud cubes are standing in a row,

being reflected deep into an unsuspecting forest lake.

Mighty files of empty windows,

reproducing the sunset´s beautiful, red neon light.

There hygienic children play on reverentially safeguarded cumulus piles

(untouched by human hands),

while in their rotation umbrellas

strictly salaried, communal child virgins hover above them.

Every day, when evening arrives, sexless vitamin workers

are swarming home, each and every one in accordance with year class,

returning to the privacy of Svea, Queen of Hormones,

carefully guarded by trustworthy bouncers.

And day becomes night, quietly. Only a trash helicopter

hums slowly from gate to gate,

propelled by a future outcast, an anarchist and poet,

life sentenced to discharge all fantasy filth.

From a distance it looks a giant hawk moth,

buzzing in front of a morning´s bouquet of pink honeysuckle,

high, o high above the glorious forests of sporty health nuts,

where no tramp ever tramps anymore.

Naturally were most of my sources written in Swedish and I refer to the bibliography of the Swedish version of this blog. However, I used some English sources as well: Boye, Karin (1994) Complete Poems translated by David McDuff. Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books. Le Courbusier (1986) Towards a New Architecture. New York: Dover. Mack Smith, Denis (1981) Mussolini. London: Weidenfield and Nicolson. Pilnyak, Boris (1975) The Naked Year. Ann Arbor: Ardis. Scott, James C. (1998) Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Spengler, Oswald (2013) Prussianism and Socialism. Indiana: Repressed Publishing LLC.