ART AND TERROR: The globalization of indifference

There are now numerous descriptions of where people found themselves on September 11th, 2001. At that time I worked at the Swedish International Development Co-operation Agency (Sida) in Stockholm. At three o'clock in the afternoon the fire alarm sirens sounded and people left peacefully their workplaces, went down the stairs and gathered on the sidewalk in front of the entrance. We stood and chatted before, after twenty minutes, we returned to our respective rooms and placed us in front of the computer screens, many of us somewhat irritated at having been disturbed by the fire drill. Soon, however, my colleagues were running around in the corridors shouting that we all had to switch over our computers to the news channels and there I could see how an airliner crashed straight into one of the Twin Towers on Manhattan, shortly followed by another plane that flew into the second tower. Fierce fires developed and after almost an hour the South Tower collapsed in a dense cloud of dust, forty minutes later followed by the North Tower. We all stared spellbound at our computer screens and not much work was done during that afternoon.

Two years later, I wrote an essay I called Reality made abstract: The terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre as an aesthetic phenomenon. That I got the idea to describe the tragedy as an aesthetic phenomenon was due to the fact that I a year earlier had seen an exhibition which, inter alia, included works by an by me previously unknown Austrian art guru with a white beard like Santa Claus. His name was Herrmann Nitsch and he had been a leading figure within an artistic group called Wiener Aktionismus.

Large blood-stained canvases covered the walls. At clinically clean towels and stainless steel tables the artist had placed surgical instruments, meat hooks, axes and saws, along with liturgical vestments, all in perfect order. Glass jars were found to contain blood and guts. Videos were projected on the walls – animals were slaughtered in front of the cameras, naked people drank blood or placed themselves inside the recently slaughtered, steaming carcasses, or allowed himself to be hung on crosses, or various types of wooden frames, all to the accompaniment of brass music composed by Nitsch.

This Austrian, versatile artist had like Richard Wagner tried to create a Gesamtkunstwerke in which he by his own account through "tangible actions" organized rituals characterized by a “healing atmosphere” intended to refashion the participants' and paying spectators' sense of existence. These Orgien Mysterien Theater, which generally lasted several days, were between 1962 and 1998 repeated close to a hundred times, in different forms and at different locations. Nitsch stated that his bizarre rituals and ceremonies were modern equivalents of sacrificial acts carried out in ancient times. Overwhelming experiences resulting in catharsis, an emotional climax, or mental collapse, provided affected persons with an empowering sense of renewal and new life.

The participants' physical contact with blood and entrails of slaughtered animals released, according to Nitschs exalted philosophizing, through pain and suffering pent-up energy flows. Other artists who identified themselves with Wiener Aktionismus, like Günter Brus and Rudolf Schwarzkogler, turned their own bodies into objects of "ritually induced" pain. Schwarzkogler´s performances gradually became increasingly violent and came to include serious forms of self-mutilation. In 1969, he committed suicide, “in the name of art", by throwing himself from the balcony of his home.

Body art in the form of body piercing, body modification, branding, scarification and suspension has over the years become an increasingly common and respected form of art, often reverentially analyzed by connoisseurs who consider it as a manner to use the human body as a language. Sometimes the distinction between torture, humiliation and art becomes hairline, or even non-existent. Human beings are reduced to objects, mere bodies. Many artists aspire achieve Verfremdung effects, i.e. dissociating spectators by separating them from what is unfolding before their eyes, while various computer generated techniques aid to blur the boundaries between illusion and reality.

Actual events become theatre, human tragedy turns into entertainment. Reality is adapted to aesthetic requirements, staged like reality shows where participants are humiliated, or even as in IS executions where victims are killed as if their deaths were part of an artfully crafted performance. Accordingly, there are both ideological and commercial interests behind this tendency to transform reality into spectacle, especially human suffering. Aesthetically pleasing photographs of war, famine and other tragedies can endow photographers with fame and income.

Nitsch sells his blood-soaked canvases at high prices and has both a museum dedicated to his art and a popular website showing the rituals he concocts. Popular documentary films depict in detail the work of police squads and social workers within squalid surroundings, characterized by human misery. The general public is by social media requested to submit accounts and footage illustrating violence and agony.

One morning, when my wife was on her way to work in New York a suicide threw himself from a tall building and was shattered against the pavement just a dozen metres in front of her. Cars stopped in the middle of the dense traffic and their drivers came rushing out with mobiles and cameras at the ready. "They are selling their pictures to newspapers and TV channels," commented a spectator.

When I at a website watched a series of photographs from September 11, I remembered Rose´s grotesque experience. The images convey an aesthetically pleasing impression. The burning towers rise against a clear blue sky, human bodies plunge to the ground alongside a background of geometric facades, intrusive images portray terrified witnesses. Have the photographers deliberately chosen their motives, searching for the best and most dramatic angles and contrasts? How much did they charge for their photographs? As the French director Jean-Luc Godard has stated: "A camera angle [actually a tracking shot] is a moral act. Style and content are one."

Aesthetical suffering and sublime death have become an integral part of our Western culture. Even our language conveys notions turning violence into something positive. We talk about gender struggle, fight for peace and human rights. War is being waged against ignorance and drugs. In science we have research fronts, new terrain is conquered, and contests are fought. Nations commemorate battles and violent incidents. Fast and furious action is commonly admired, far more than lengthy, patient negotiations. The immediate, revolutionary and violent arouse attention and appreciation.

An utterly ruthless mass murder, like the attack on the Twin Towers, could even be interpreted as a work of art, something to watch, be horrified by and commented upon from the cosy comfort of sofas placed in front of our TV sets, from which we on September 2001 could watch how condemned, desperate people helplessly crowded by the windows of the upper floors, while others threw themselves headlong towards the ground, with arms squeezed to their flanks to increase the speed and relentlessness of death.

Some artists openly express their appreciation of the tragedy as a work of art, like the strange and genius declared composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, who when he during a press conference in Hamburg was asked by a journalist if the attack on the Twin Towers had affected him. Could such an unspeakably cruel and fanatical act be harmonized with the human concord and peace Stockhausen stated he intended to express through his latest work Hymnen. To the consternation and indignation of most people reached by his message the composer explained:

Well, what happened there is, of course—now all of you must adjust your brains—the biggest work of art there has ever been. The fact that spirits achieve with one act something which we in music could never dream of, that people practise ten years madly, fanatically for a concert. And then die. [Hesitantly.] And that is the greatest work of art that exists for the whole Cosmos. Just imagine what happened there. There are people who are so concentrated on this single performance, and then five thousand people are driven to Resurrection. In one moment. I couldn't do that. Compared to that, we are nothing, as composers. [...] It is a crime, you know of course, because the people did not agree to it. They did not come to the "concert". That is obvious. And nobody had told them: "You could be killed in the process."

Stockhausen apparently belonged to the faction of geniuses who seem to exist beyond ordinary human life. Soaked as he was in the Indian mystic Sri Aurobindo's philosophy and astrological beliefs Stockhausen was known to come up with, mildly speaking, oddball statements:

I have been educated on Sirius and want to return there, though I still live in Kürten near Cologne. Sirius is much more spiritual. Between idea and realization there is almost no time span at all. What is known here as the “audience”, i.e. passive observers, does not exist there. There everyone is creative.

Statements that by admirers and followers might be interpreted as profound, but to others may indicate some kind of mental disorder. When Stockhausen wanted to explain and defend his controversial interpretation of the attack on the Twin Towers, he declared:

I pray daily to Michael [the Archangel], but not to Lucifer. I have renounced him. But he is very much present, like in New York recently. At the press conference in Hamburg, I was asked if Michael, Eve and Lucifer were historical figures of the past and I answered that they exist now, for example Lucifer in New York. In my work, I have defined Lucifer as the cosmic spirit of rebellion, of anarchy. He uses his high degree of intelligence to destroy creation. He does not know love. After further questions about the events in America, I said that such a plan appeared to be Lucifer's greatest work of art. Of course I used the designation "work of art" to mean the work of destruction personified in Lucifer. In the context of my other comments this was unequivocal.

Stockhausen's concept of art is influenced by his perception of religious ceremonies and rites. He is inspired by Japanese Noh Theatre, combined with Jewish-Christian and Vedic traditions. During a deep personal crisis in 1968, Stockhausen came to read a biography of the Indian mystic Sri Aurobindo, whose ideas affected him profoundly and as a result his musical creativity changed fundamentally. It became mystical and religious. Stockhausen's comprehensive work Licht, Light, consists of seven parts, each part, or rather opera, is constructed as a performance on a given day of the week and named accordingly - Thursday, Friday, Saturday, etc.

Stockhausen has explained that his work is inspired by Aurobindo's theories concerning Agni, the Hindu god of fire, notions inspired by nuclear physics, European and Hindu philosophy. The opera suite's characters are expressed either through instruments, singers or dancers, and some parts are sung to improvised lyrics in simulated, or invented, languages.

Sri Aurobindo (1872 - 1950) was an Indian guru educated at Cambridge University in England. After returning to India he served under the Maharajah of Baroda. He became involved in India's struggle for liberation and was in 1908 sentenced to prison on charges of plotting an assassination attempt on a British Chief Justice. When Aurobindo was aquitted after one year in captivity he had become a completely changed man due to a religious revelation inside the prison. He began preaching something he called “integral yoga”, a philosophy that was said to constitute a "dynamic manifestation" of the Absolute, a link between the World Soul and our individual mind. If we properly apply the teachings of integral yoga, we would be able to develop a super-consciousness that eventually will transform us into divine beings. According to Sri Aurobindo, a Supermind is part of a higher realm of perfect being-consciousness, elevated above common thoughts, life and matter. Such a state of perfect existence/consciousness allows for a creative, unbound mind.

Sri Aurobindo's main supporter and heir, Mirra Alfassa, was born a Jew in Paris in 1878, however Sri Aurobindo declared that she was the incarnation of the Divine Mother, and Mirra was accordingly called “Mother” by the sect members. In February 1956, The Mother declared that the Supermind´s presence on Earth was no longer a promise, but a reality. The most blind, the most unconscious, would soon be forced to realize this fact, which was revealed to her through a mighty vision:

This evening the Divine presence, concrete and material, was there present among you. I had a form of living gold, bigger than the universe, and I was facing a huge massive golden door which separated the world from the Divine. As I looked at the door, I knew and willed, in a single movement of consciousness that “the time has come,” and lifting with both hands a mighty golden hammer I struck one blow, one single blow on the door and the door was shattered to pieces. Then the Supramental Light and Force and Consciousness rushed down upon the earth in an uninterrupted flow. […] I went up into the Supermind and did what was to be done.

Stockhausen, who was hailed or condemned as an odd personality, considered himself to be in possession of a super mind and like so many other extraordinary celebrities, not least artists who are aware that they possess an ability beyond the ordinary, such an insight, even if it is coupled with tributes to love and tolerance, might give rise to tyrannical and egocentric behaviour. Stockhausen's sister, Kathrina Ernst, stated:

I haven't had any contact whatsoever with Karlheinz for 30 years. I did make some overtures a number of years ago and went to meet his daughter, who was playing in a concert nearby. But apparently Karlheinz then forbade the children to talk to me. I really don't know why. He lives in a different region from normal-thinking people.

Marinella, Stockhausen's piano-playing daughter changed her last name and refused to deal with her father after his statement in connection with the disaster in New York.

Karlheinz Stockhausen might be considered as one of the great musical geniuses of the twentieth century's second half and have had a great influence and many followers. Nevertheless, he has generally been regarded as a very peculiar man, something of a stranger in existence; eccentrically dressed and with an aptitude for cryptic statements. It seems as if his counterpart in the world of painting, graphic arts and movies could be Andy Warhol.

Without doubt, both Warhol and Stockhausen may be considered as "geniuses" in the ancient, Latin sense. A genius was originally perceived as a spirit who accompanied every human being from birth to death. The word was akin to genitus, which meant "to animate, create, produce.” Unusually creative people were considered to be endowed with extraordinary potent geniuses. In that sense it is undeniably that Warhol and Stockhausen were geniuses, since both were extremely creative.

Warhol was also religious, but unlike Stockhausen he was a Catholic. The priest of his home parish, St. Vincent Ferrer on Manhattan, revealed after Warhol's death that he almost daily came to Mass, though the artist neither participated in the Eucharist, nor in confession. The priest said that Warhol always placed himself in the back of the church and sometimes knelt throughout the entire ceremony: "I assumed he was afraid of being recognized." However, Warhol frequently participated in charity campaigns when he anonymously worked as a volunteer in shelters for the homeless. Warhol's brother explained that Andy was "really religious, but he didn't want people to know about that because [it was] private."

That may seem strange since much of Warhol's art revolved around sexual perversions, voyeurism and callousness. In his speech, appearance and behaviour he often expressed an extreme alienation, at the same time as he, just like Stockhausen, was highly dependent on having submissive, but hard working, people around himself:

The story of Andy Warhol is the story of his friends, surrogates, and associates. It would be easy to narrate his life without saying much about him at all, for he tried to fade into his entourage.

Like many artists Warhol was endowed with an ability to exploit his environment to the utmost, without giving much in return to all those who stood up for him and supported him. He had a tendency to give himself credit for the self-sacrificing work of others:

He had a peculiar style of treating people, as if they were amoebic emanations of his own watchfulness. In practice, his friends and collaborators often found themselves erased – zapped into nonbeing, crossed off the historical record, their signatures effaced, their experiences absorbed into Warhol's corpus. To work with Warhol was to lose one´s name.

Andy Warhol's personality was to a high degree the result of a conscious effort, a way to manage his unusually strong sense of alienation and use it to interpret and exploit his environment. And as the true artist he was, he managed to portray the emptiness and cruelty that thrived around him. One of Warhol's biographers, Wayne Kostenbaum, wrote:

Many of the people I´ve interviewed, who knew or worked with Warhol, seemed damaged or traumatized by the experience (Or so I surmise: they might have been damaged before Warhol got to them). But he had a way to shed light on the ruin – a way of making it spectacular, visible, audible. He didn´t consciously harm people, but his presence became the proscenium for traumatic theater. Pain, in his vicinity, rarely proceeded linearly from aggressor to victim; trauma, without instigator, was simply the air everyone around him breathed.

As a seemingly passive catalyst of behaviour and creations, a cool observer of traumas and disasters, Warhol and his art seem to be present in the context of interpretations of the Twin Tower catastrophy, even if he was deceased long before it occurred.

Shortly after the Twin Towers´ collapse, I listened one morning to a cultural programme on the radio. Initially I listened indolently, but gradually I became fascinated. I had first perceived the story as evolving around a gallery in Berlin, which presented an exhibition with a name like Silence of Our Time, or something similar. I remembered it as if projectors had been turned on day and night, while they on three walls presented live images in real time – a view of Fernsehturm in Berlin, the Twin Towers in Manhattan and a Trappist monastery somewhere in Southern France. Despite the fact that the cameras recorded scenes from two bustling mega cities it appeared as if these sequences radiated the same atmosphere of silence and calm as the one prevailing among the monks in southern France, where the brethren with long intervals silently passed in front the camera. Looking at the monotonous imagery visitors could experience a meditative silence akin to that which reigned inside the monastery. An unknown visitor was present in the gallery at three o'clock in the afternoon on the 11th September and when, in the compact silence surrounding him he witnessed how the planes crashed into the Twin Towers. I found it hard to explain why the story gripped me so profoundly.

I included my rather indistinct memory of the programme in my essay. Though before I did that, I checked the programme listings for cultural news on the Swedish radio and searched lists of cultural events in Berlin for September 2001 - but without finding anything about that mysterious exhibition and in my essay I had to write that "maybe it had been a dream". However, I did not cease to ponder about it all, until I one day found a book that described the background to the project. Admittedly, I had gotten a lot wrong, but basically my perception of it all had been more or less correct.

Let us return to Andy Warhol - A summer evening in 1964, or to be more exact, six minutes passed 8 pm, Andy Warhol and Jonas Mekas began filming the Empire State Building from an office window at the Time-Life Building’s forty-first floor. Warhol was meticulous about the fact that Mekas had to make an uninterrupted sequence and various fast unloadings and loadings of the photographic film had to be done. They ended up with a black-and-white movie with a time span of eight hours and five minutes. Actually, the filming had taken six hours and thirty-six minutes and was made with a standard twenty-four-frames per second, though at the premier the movie was by mistake projected with sixteen frames per second, making it almost two hours longer than the original sequence. After that Andy Warhol insisted on the longer screening.

No one knows why Warhol wanted to make an already boring movie even lengthier. He never gave an explanation for his decision, not even to why he had made the movie, other than “Empire State Building is the star of New York and deserves a movie of her own.”

The action? The movie begins with indistinct flickering on the white screen; gradually the Empire State Building’s characteristic radio mast and upper floors become visible against a setting sun. Floodlights are turned on, illuminating the façade, while on different levels lights go on and off behind the office windows. Night falls and it gets darker around the building. After six and a half hours, the floodlights are turned off, no light is coming from the windows and the movie screen becomes almost black during the one hour and thirty-five minutes that remain of the screening. Andy Warhol’s Empire has seldom been presented in its entirety and few have seen it from beginning to end. Warhol actually forbade any broadcasting of shortened versions.

In 1991, the German video artist Wolfgang Staehle launched a web network for art and artists, calling it The Thing, maybe alluding to Kant’s das Ding an sich, the thing itself, meaning an object, concept or event that can be known (if at all) only through the mind, without the use of the physical senses. The opposite is true about a phenomenon, which can be apprehended by the use of the five senses.

You joined Staehle´s network by applying for membership through an e-mail, but the system became increasingly sophisticated and in 1995 The Thing was turned into a still active web site. The Thing has its main office in New York, more particularly in Chelsea on Manhattan and from its office windows you have an excellent view of the Empire State Building. Accordingly, it was quite natural for Wolfgang Staehle, who had made his name by filming long sequences of different landscapes, to attempt a new version of Warhol’s Empire. Staehle placed a digital camera in one of the office windows and aimed it at the Empire State Building. Every second between 1999 and 2004 the camera took a picture of the skyscraper’s upper floors and in a continuous stream the sequence was transmitted through The Thing’s web site. The project was called Empire 24/7.

An even more sophisticated project emanated from Empire 24/7. An exhibition originally called To the People of New York and it began to be screened on a Saturday, 1st of September 2001, at an art gallery in Chelsea called Postmaster’s Gallery, not far from The Thing’s offices.

In two darkened rooms the visitor was confronted with ongoing sequences of digital images projected directly on the white walls. In the first room a horizontal panorama of lower Manhattan was presented on an entire wall. Two digital cameras delivered a steady stream of pictures from a building on the Brooklyn shore. The viewer could see a moored cargo ship with the Brooklyn Bridge in the background and behind the bridge span – The Manhattan Skyline, with the Twin Towers, Chrysler Building and Empire State Building. On the opposite wall was a vertical, permanent view of the Fernsehturm in Berlin. A digital camera was directed towards the slowly rotating TVtower, while a stream of pictures was transferred directly to the Postmaster’s Gallery and projected on the wall. Standing in the middle of the first room the visitor also had a view of an adjoining room with a horizontal projection of another fixed panorama, though not at a Trappist monastery in southern France, but a view of a Medieval, fortified monastery in Comburg, opposite the town of Schwäbish Hall, Wolfgang Staehle’s birthplace in the German state of Baden-Württemberg.

The exhibition received good reviews. Art critics pointed out the meditative atmosphere that reigned inside the gallery, as well as a somewhat eerie sensation of the fact that at exactly the same moment you were able to observe widely separated places; the gallery space, Lower Manhattan, Berlin and Comburg. The visitor was confronted with a metropolis, a TV tower and a monastery; each place representing some form of communication – the exchange of goods through the cargo ship and the bridge in New York, transmission of information through the TV tower in Berlin and a spiritual connection represented by the monastery in Comburg. In the gallery all three places were encompassed by calm and peaceful stillness.

On top of that the exhibition illustrated a single man’s lifespan, landscapes seen through a temperament. In a sense the projections represented parts of Staehle’s personal biography, by exposing his birth place, Comburg, the place where he learned his trade, Berlin, and finally the city he had chosen for acting out his creative urge – New York, the city that never sleeps, the communication hub of the entire world.

Not many visitors were attracted to the exhibition, though that was in a way an advantage since the emptiness supported the meditative faculty of the place. A visitor could undisturbed stand in front of a projected landscape, allow her/himself to sink into it and ponder about the mystery of human existence, our place in universe, the stillness behind all the fuzz of life, even within a hectic metropolis.

I do not know if anyone was in the gallery at 8:46 in the morning of September 11. If someone had been there s/he would, within the quiet stillness, have seen how an airliner, silvered by the morning light, crossed over a bright blue sky and crashed in to one of the Twin Towers, without a sound, while the cameras registered it all and subsequently also transmitted images of another airplane crashing into the second tower. How the enormous buildings collapsed in compact clouds of dust and debris, slowly lifting upwards towards an imperturbable translucent blue.

Perhaps my fascination with the imagined scene has something to do with the silence and emptiness of the gallery. How an event is reflected in another room, in another place and thus bestowed with an alternative interpretation, a different meaning, a different depth. There is also, as in Warhol's art, the mystery of alienation and exclusion. Where are we in all that is happening around us? The Earth spins on in a cold and desolate universe, while each of us cling tightly to our small lives and concerns.

I also think about the terrorists who crashed the planes into the Twin Towers. It has been said that during their pilot training in the US, they were for obvious reasons, quite uninterested in learning how to land an airliner. I consider this as a good illustration of what I perceive as the essence of terrorism.

The suicide pilots obviously strove to make an impact, achieve some sort of change. Though they never learned anything about the actual consequences of their actions. They lacked a comprehensible objective. They did not improve on anything, they wanted a change, but why, for what reason, to what expected result? For them there was no "afterwards" and they thus acquitted themselves from any responsibility for their horrible, murderous crime. They will never be accountable for their mass murder of innocent people.

The suicide pilots strike me as hopelessly confused as the members of the groups that terrorized world in the 1970s - the Baader-Meinhof and Red Brigades in Europe, or Sendero Luminoso in Peru. Violence and terror became ends and means, nothing more. A vicious circle. The future did not exist for them, it was an illusion, an utopia based on elusive fancies. And for this deplorable chimera they killed, maimed and destroyed the lives of thousands of innocent people.

The silence in the Postmaster's Gallery contrasted to President Bush's reaction and ferocious statements. His jingoistic, martial appeal, far from a real war´s blood, guts and suffering:

There are some who, uh, feel like that, you know, the conditions are such that they can attack us there. My answer is: bring 'em on. We got the force necessary to deal with the security situation.

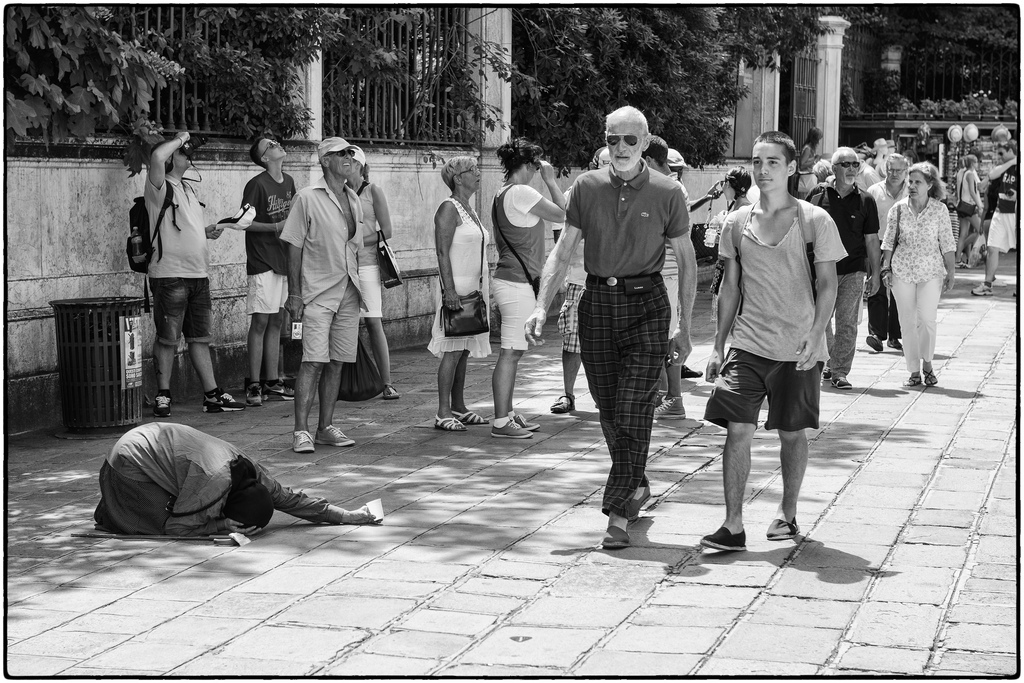

We are now living with the consequences of that fateful decision, like the suicide pilots we are enveloped by an inhuman machinery that we do not have full control over. We cannot land, others have to do it for us. We are like a gallery visitor who helplessly watched the planes crashing into the Twin Towers, and seem to have ended up in Warhol's world of surface and voyeurism. We are a part of what Pope Francis has called "the globalization of indifference".

Badura-Triska, Eva and Hubert Klocker (ed.) (2012) Wiener Aktionismus: Kunst und Aufbruch im Wien der 1960er-Jahre. Wien: Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König. Grauel, Rolf (1998) “Lichtgestalten” in Zeit Magazin No. 15. Kostenbaum, Wayne (2003) Andy Warhol. London: Phoenix. Kurtz, Michael (1988) Stockhausen – eine Biographie. Kassel/Basel: Bärenreiter. Lundius, Jan (2003) ”Reality made abstract: The terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre as an aesthetic phenomenon” in Lundmark, Fredrik (ed.) (2004) Culture, Security and Sustainable Social Devolpment after September 11. Stockholm: Gidlunds. Nitsch, Herrmann Homepage https://www.nitsch.org/index-en.html. O'Mahony, John (2001) “The Sound of Discord” in The Guardian, 29 September. Sri Aurobindo (2006) The Life Divine. Twin Lakes WI: Lotus Press. Tribe, Mark och Jana Reese (2006) New Media Art. Berlin: Taschen Books. Van Vrekhem, Georges (2014) Beyond the Human Species: The Life and Work of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother. Peachtree City GA: Omega Books.