JACK THE RIPPER: Art, mirror images, fascination and mania

One of mine and my youngest daughter’s pleasures is to visit IKEA, a strange place where I cannot avoid being fascinated by the small, decorated rooms. They make me think of reconstructions of antique environments which are to be found in museums. The only difference is that at IKEA people move around among the furniture. Otherwise, the IKEA environment is just as strangely removed from reality as the museum displays.

Recently I did in an art magazine discover the works of the American artist Rikki Nihaus – Swedish Landscapes. Contour-sharp, hyper-realistic oil paintings showing how the same man, wearing a gray suit and black tie, places himself among IKEA's furniture displays. Perhaps these artworks might be considered as a critique of our consumer society. I do not know. The images are emotionally cold, testifying to surface and alienation. The man seems to e something in common with the furniture – rigid and devoid of signs of expressions he reflects an illusion of “reality”, that is nothing less than lifeless sterility.

One of Nihaus’ paintings appears to reflect a painting by the English artist Walter Sickert'– Ennui, Boredom. A cigar smoking man stares blankly at something beyond us. while a woman is leaning against a chest of drawers seemingly looking straight into the wall, or possibly she is dreamily looking at a painting. It is hard to establish which is the case.

In Nihaus’ Swedish landscape, the man also looks at something outside the picture and just as the older cigar-smoker in Sickert's painting has a half-filled glass in front of him, and possibly an ashtray, or a matchbox, the well-dressed man sitting among IKEA’s furniture display has glass and porcelain in front of him. The woman behind him turns away. The two IKEA-visitors have no contact whatsoever. O each other they are complete strangers. IKEA is here appearing as a Twilight Zone, a world far beyond the “real” life.

On the contrary, the persons in Sickert’s painting might know each other far too well, in any case they have no contact either.

Walter Sickert (1860-1942) was undoubtedly, along with his contemporary Philip Wilson Steer, England’s foremost impressionist, although his misanthropic disposition makes Sickert often seem to be in a twilight zone between impressionism and expressionism. Below we see the serious Sickert and a more jovial Steer in a painting by Henry Tonks.

Sickert painted atmospheric landscapes from Venice, Dieppe and the English countryside, but made himself best known as a city painter.

His representations of taverns and cabarets have a certain liking to Degas, at least in terms of motifs, although Sickert makes use of a more fragmented colour surface and diffuse contours.

In 1883, Sickert met Degas in Paris and was then deeply impressed by him and his art. Like Degas, Sickert depicts entertainment venues and portrays prostitutes, and like the virtuoso Frenchman, Sickert used unexpected angles, bold cuts, and paid attention to subtle light shifts and reflections.

However, if Degas in his painting seems to find himself in the middle of life, Sickert, who quite often was overtaken by depressions, seem to express a feeling of exclusion, paired with a negative view of humanity. Sickert used to state that he regarded humanity as divided between "caretakers and patients".

In London, Sickert liked roaming around in poor, run-down neighborhoods. In his pictures of prostitutes, Sickert does not seem to meet them like in Degas in brothels, but in shabby hotel rooms, and he portrays them with a ruthless, almost contemptuous realism.

It is possible that Sickert, despite having a several girlfriends, had a degrading view of women. In fact, he explicitly forbade women to participate in the artists’ group he founded in 1911 and named The Camden Town Group. For three years, sixteen artists met regularly in Sickert’s studio and arranged joint exhibitions. Several of them were already well-known, like Robert Bevan, Augustus John, Wyndham Lewis and Duncan Grant.

Robert Wood was an artist who, like Sickert, lived in Camden. However, he was too young and unrecognized as an artist to be honoured with membership in an illustrious artist fellowship. Wood was primarily an engraver and was working as designer at the reputable London Sand Blast Decorative Glass Works. Since he and Wood shared the same interests, Sickert was probably acquainted with him. Like Sickert, Wood was often seen in pubs, restaurants and various places of entertainment and was known as a somewhat blasé, though nevertheless a charming man.

Emily Dimmock, who occasionally worked as a prostitute, was in 1907, in an apartment she shared with a railway worker, found with the throat slit. The couple was not married and when the man was away on lengthy work shifts Emily received her former customers in the couple's shared apartment. The perpetrator had killed Emily in her sleep he had deed unseen disappeared from the crime scene.

The murder became a sensation and was followed up by a number of sensational newspaper articles. It was wildly speculated that Jack the Ripper had reappeared. Robert Wood’s former girlfriend, Ruby Young, who was a prostitute as well, knew that Wood had an affair with the murdered Emily. The artist forced Ruby to provide him with a false alibi for the night of the murder. Ruby, however, told what happened to an acquaintance, who went to the police who when they pressed Ruby and furthermore showed her a postcard they had found in Emily's apartment, she recognized Wood’s handwriting. Ruby's testimony was fitted in with the fact that several of Wood’s acquaintances on the night of the murder had seen him together with the murdered Emily. Wood was arrested, but was acquitted after an extraordinary skillful defense.

Through his handsome, youthful appearance and calm demeanor, Wood had during the trial been able to charm a large part of the audience, while others became disturbed by his light-hearted, obviously careless behaviour. During his trial and detention, Wood made a number of sketches which were immediately published in the press. After his acquittal, the suspected killer lived a relatively unnoticed and quiet life until his death in 1966.

Walter Sickert was a trained actor and could easily identify with different people, not least suspected murderers. He became famous after devoting several drawings, etchings and paintings to what he called The Camden Town Murder. All these works of art depicted how a dressed man is seen in the same room as a naked woman lying on a bed.

Sickert had previously made himself known for renderings of “vulgar” nudity and his depictions of the Camden Murder created a widespread scandal. Rarely had a well-known artist in such a brutal manner manifested his engagement in an actual murder, which furthermore hinted at sexual violence. Sickert went out in defense. In an article he opposed the shallow and enticing nudity of salon art and instead advocated an uninhibited realism:

An inconsistent and prurient puritanism has succeeded in evolving an ideal which it seeks to dignify by calling it the Nude, with a capital “n,” and placing it in opposition to the naked. An interdict to representations of the naked figure, such as was in force in certain Catholic countries in the middle ages is worthy of respect, and is consistent. The modern flood of representations of the vacuous images dignified by the name of the Nude, represents an intellectual and artistic bankruptcy that cannot but be considered degrading, even by those who do not believe the treatment of the naked human figure reprehensible on moral or religious grounds.

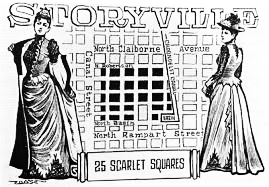

From time to time, Sickert painted naked women with disfigured faces and bodies, reminding of the work of Ernest Joseph Bellocq (1873–1949), a commercial photographer who in New Orleans devoted himself to portrait - and landscape photography. Bellocq came from a well-to-do family and was something of a dandy, who according to friends and acquaintances had no other interests other than photography. Bellocq was attracted to Storyville, the city's shabby, red light district, the birthplace of jazz and an abode of disgraceful entertainments. Bellocq spent much of his time in the brothels and opium dens located to these infamous neighbourhoods.

After his death, Bellocq became known for his previously unknown photographs of nude prostitutes. Pictures that have made Bellocq the subject of a number of films and biographies, often of a lugubrious kind. The main reason for this interest is that several of the naked women portrayed in Bellocq’s photographs have had their faces scraped away. Something done already while the photo emulsion was still moist, i.e. the liquid mixture of gelatin and photosensitive silver salts that early photographers used to develop their images.

That Bellocq acted in such manner remains a mystery, especially since his nude models on several images have their faces intact. However, Bellocq often provided his models with face masks.

Bellocq’s and Sickert’s nudes are through their rather shabby surroundings reminding of Francis Bacon's numerous depictions of distorted, helplessly naked and almost massacred figures twirling around on soiled beds.

Bacon’s occasionally quite repulsive pieces of meat, placed as they are on disheveled beds, bear a resemblance to the revolting forensic photographs taken of Jack the Ripper's victims. Jack the Ripper was the designation for an unknown serial killer who between August and November in 1888 murdered at least five women, the so-called Canonical Victims, this since there might be several more victims of The Ripper’s murder spree.

The killings came to prominence through their connection with social and moral squalor of the undiscovered assassin’s hunting grounds within Whitechapel, one of London’s East End’s most infamous neighborhoods, immortalized by Gustave Doré’s etchings in Jerrold Blanchard’s London, A Pilgrimage from 1869 and Jack London’s impressive reportage book The People of the Abyss, from 1903.

Murder was common in the East End, not the least did its poor and unprotected prostitutes live dangerously. The general public’s anxiety and imagination were further provoked by the Ripper’s defilement of his victims. He opened their corpses opened and removed internal organs. In some cases, he arranged severed body parts together with various objects in the same room where he had committed his horrendous crimes. This was done in such a way that it seemingly suggested macabre rituals. In other cases, he took some of the organs with him. One of the the Ripper’s victims was Swedish port of Gothenburg.

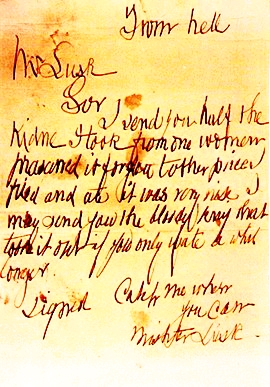

When the commotion was at its greatest heights, the police and press received hundreds of letters whose senders pretended to be Jack the Ripper. Most of them could be rejected as written by journalists, or by people who wanted to enjoy the effect of their antics. Several researchers believe that all letters are fake, but one of them is, due to its special content, often highlighted. This so-called Letter-From-Hell was addressed to the leader of a civic guard which assisted the police force in its search for Jack the Ripper.

The letter was sent in a small box that also contained half a human kidney. The grotesque object may have originated from one of the victims, Kate Eddowes, who suffered from the same disease as the sent kidney showed signs of. The letter writer, it is the only letter that is not signed with “Jack the Ripper”, said he had fried and eaten the other half of the kidney. The misspelled, strangely formulated and awkwardly texted letter eventually disappeared during the London Blitz. It got its name from its introductory words “From Hell”.

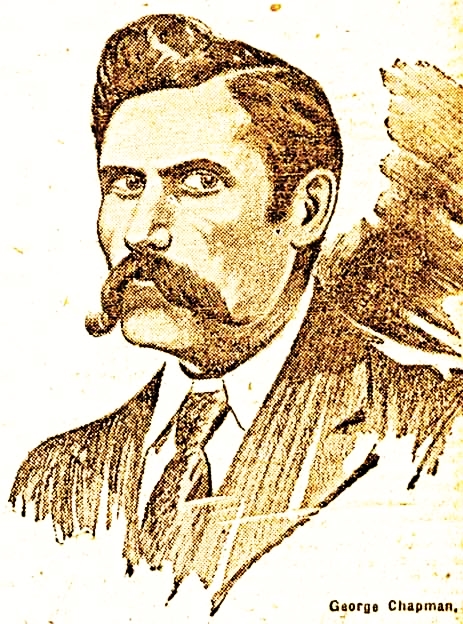

Jack the Ripper’s rampage among East End’s prostitutes ceased as abruptly as it had begun. Had he simply taken his own life? Or was he perhaps a well-to-do gentleman from the city's upper classes who assumed that hunters were on his track? In any case, the gruesome murders gave rise to a plethora of “investigators” who, from 1888 onward, have been presenting a myriad of theories and assumptions about who the killer might have been. There is no lack of articles, books, plays, musicals, operas, comic books, paintings, rock music and not the least novels dealing with Jack the Ripper. The perpetrators have been identified as teachers, thieves, lawyers, surgeons, butchers, mental patients, vampires, demons, doctors, hairdressers, blackmailers, arsonists, royalty, writers, artists, businessmen and police officers. Jews, Freemasons and priests have been suspected. In addition to being English, Scots or Irish, the alleged perpetrators have been Poles, Russians, Americans, Germans, French, Belgians, Italians, or Australians.

.jpg)

After presenting his artistic renderings of the Camden Murder, Sickert began to expose an increasingly immersive interest in Jack the Ripper. He continued to paint naked female figures on beds in impoverished environments and even imagined that his home on 8 Morning ton Crescent once had housed Jack the Ripper. His landlady had assured him that a tenant, a young man studying to be a veterinarian, who had rented the apartment in 1881, had been no less than the infamous serial killer.

That Sicker was engrossed by his interest in brutal murders has been observed stated, among others, by his artist colleague Marjorie Lilly (1891-1980), who in her memoir Sicker: The Painter and His Circle from 1971 described how Sicker when she once visited him was obsessed by a “burning craze for crimes personified in Jack the Ripper.”

The artist and gallery owner Helen Lessore (1907-1994), who in the thirties spent a lot of time with Sickert and wrote several articles about him, also pointed out his great interest in murder scenes and claimed that she and Sickert often visited places where heinous crimes had been committed. In parentheses it might be mentioned that it was Lessor who first paid serious attention to the young Francis Bacon’s art and she did in 1953 in her London gallery Beaux Arts arrange the artist's first exhibition, when among other outrageous works his later so famous Screaming Pope was exhibited.

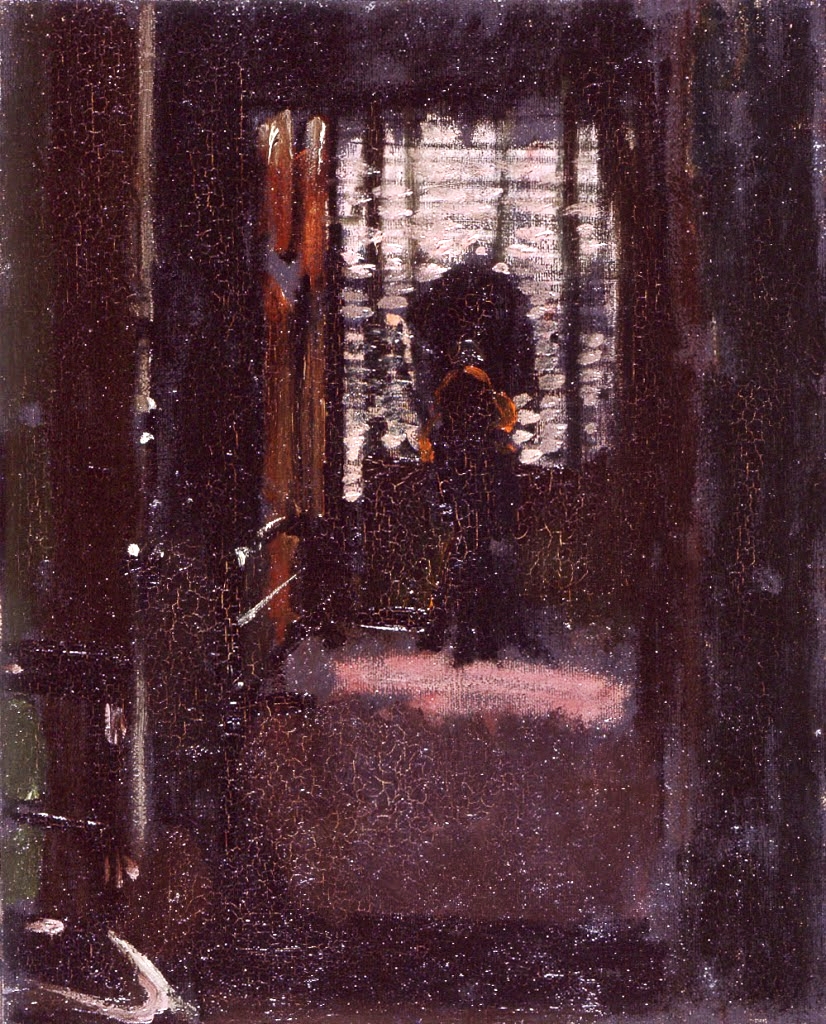

Several of the paintings and sketches that Sickert made of his bedroom he named The Bedroom of Jack the Ripper. In a particularly enigmatic version we see the room through an open door. It is dark and contours are blurry, light enters from gaps in the window blind. It appears as if a menacing figure is standing with his back to us, looking out through the narrow openings in the window screen – the Death, Jack the Ripper? In comparisons with several other of Sickert’s representations of the same room, we realize that it is in fact not the shape of a dark male figure, but a mirror.

Did Sickert often stand in front of that mirror while pretending to be Jack the Ripper? A fantasy he possibly portrayed in his depictions of disfigured, naked women? He made a large number of paintings of naked women lying exposed on a bed in the same room. Were they fantasies about slaughters by Jack the Ripper?

Sometime in 1969, Helen Lessore, who was sister-in-law to Sickert's third wife, was in her gallery visited by a peculiar man and thus began a new chapter in the strange story about Jack the Ripper.

Joseph Gorman, a rather unsuccessful artist and art restorer, claimed to be the illegitimate son of the otherwise childless Walter Sickert. Gorman had sought out Lessore because she was known to be an authority concerning most matters related to Walter Sickert, if she accepted Gorman's story it would be an important part of his intents to prove that he was Sickert’s son.

It was not only Walter Sickert’s fatherhood that Gorman revealed to Lessore, most sensational was that according to him had Jack the Ripper not at all been a crazy serial killer. The five women had actually been murdered as part of an effort to hide a scandal within the British royal family. According to Gorman, the killer had been no less than the respected Sir William Withey Gull, one of Queen Victoria’s trusted medical doctors. Walter Sickert had also been involved in the bloody and sordid drama.

Through Helen Lessore, the BBC got in touch with Joseph Gorman, or Joseph Sickert as he now called himself and this contact became the origin of a conspiracy theory that still haunts movies, books and newspapers.

In 1973, the BBC did in six episodes broadcast a series dealing with Jack the Ripper. The programs were in part presented as a discussion between two “detectives” and interspersed with dramatized scenes taking place in the 1880s. In episode six, Joseph German appeared and told his astonishing story.

.jpg)

According to Gorman, his grandmother – Annie Elizabeth Crook, had secretly been married to the English heir to the throne, Albert Victor, and had a daughter with him. In connection with this rather incredible story, German claimed that the Ripper murders were part of a conspiracy to silence a potential scandal by murdering everyone who knew that Albert Victor had begotten a daughter with a commoner, a woman who worked in a tobacco shop.

Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, was the eldest son of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and later King Edward VII. Accordingly Albert Victor was in second place in the British succession order. However, he died in 1892, only 28 years old, and since Edward VII died childless, this would actually mean that Joseph Gorman’s mother, Albert Victor's daughter, had been the rightful heir to the British throne and that Joseph Gorman thus was a prince. However, when Edward VII died in 1910 it was Albert Victor’s son, George Frederick Ernest Albert, who became British King under the name of George V.

According to Gorman, Walter Sickert knew everyone involved in the conspiracy to cover up the fact that Albert Victor had a daughter. They were all Freemasons. Sickert also knew Since Albert Victor, Edward VII and the future George V all were members of the same Masonic lodge as Sickert he was personally acquainted with all of them. That Sickert knew George V is partly based on the fact that he made several portraits of him. However, like so many other of Sickert's “portraits”, they were actually based on newspaper clippings.

At the request of her Masonic friends, Sickert, still in accordance with Gorman’s imaginative tale, employed a nanny to Prince Albert Victor’s secret daughter, whose mother by the conspirators had been locked up in a mental institution. The nanny was, in fact, a prostitute, Mary Jane Kelley, who, when she learned about the truth of the child’s ancestry, began blackmailing the British royal family. Mary Jane Kelley became Jack the Ripper’s last victim, before whom Sir William Withey Gull, on behalf of the royal family and with the help of his Masonic colleagues had murdered four of Mary Jane’s friends, they were all prostitutes, making it all appear as crimes committed by a perverted misogynist.

Joseph Gorman/Sickert had claimed that he had been told the sordid story by his alleged father, Walter Sickert, who according to him had had an affair with Prince Albert Victor’s alleged daughter, who thereby had became the mother of Joseph Gorman/Sickert.

The reason I became interested in this singular story was that while I in 1983 was teaching history of religions in Santos Domingo was approached by one of my adult students who came up to me and greeted me with a somewhat peculiar handshake. He blinked conspiratorially while declaring: “I understand that you are one of us.” When I seemed to be completely unaware of what he meant, he whispered: “Los Masonicos” the Freemasons. Somewhat later I discovered that handshake on the cover of a book by Stephen Knight The Brotherhood, which in addition to providing an interesting account of the history of the Freemasons presented a number of more or less fantastic conspiracy theories about this legendary society. In Knight’s book I found Joseph Gorman’s ingenious story, which the author apparently had taken very seriously.

After watching the BBC’s series about Jack the Ripper, Stephen Knight (1951-1985) had sought out Joseph Gorman in his shabby apartment in north London. For hours, Knight had been sitting and with great fascinated listened to the mythomaniac’s cunningly constructed stories. At first, however, Knight had been extremely doubtful whether the whole thing could be true or not and accordingly dug himself into investigative journalism, which led him to discover quaint contexts and inexplicable coincidences. Finally, Knight became convinced that Gorman was largely telling the truth. The result was a 1975 bestseller – Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution, which captured public imagination not only because of the fantastic story told by Knight, but also due tom his “discovery” of a high-level conspiracy. About hidden forces at the heart of British society – the lugubrious manipulations of Masons, who for centuries had shaped English politics. Knight’s book thus became another contribution to the nutty nets that are spun around what is conceived to be global, damaging and outright dangerous intrigues generated and stage-managed by powerful, secretive associations.

An enraged Gorman did however partially destroy Knight’s cleverly constructed theories about Free-masonic manipulations. Knight had slightly changed German's tale by emphasizing a suspicion that Walter Sickert was more involved in the murders than previously assumed. Knight even hinted that it was Sickert and not Dr. Gold who was identical with Jack the Ripper. Joseph Gorman, who stubbornly continued to claim that he was Sickert’s son, went to The Sunday Times and admitted that he had invented most of his wondrous story.

Nevertheless, Knight did not give up and wrote The Brotherhood, another bestseller in which he further developed his theories about the Freemasons’ control of British politics, yes – how they actually had a frightening influence on the whole of English society. By that time, Knight had become one of the disciples of Bhagwan Rejnesh, “Osho”, and called himself Swami Puja Deba. Two years after the release of The Brotherhood, Knight died of a brain tumor.

Knight’s theories gave birth to several sequels that spanned both his conspiracy speculations and the possibility that Walter Sickert had been Jack the Ripper. When it came to the conspiracy, Alan Moore's and Eddie Campbell’s “graphic novel” from 1998 became influential, mainly because it formed the basis of the Hughes brothers’ 2001 film From Hell.

In their film, the brothers Hughes transform Walter Sickert into Prince Albert Victor, who when he moves to the East End and marries Anne Crook pretends to be the artist “Albert Sickert” (sic). In their graphic novel, however, Moore and Campbell downplay Sickert’s role and concentrate their tale on the physician and Freemason William Gull, who is portrayed as a misogynistic lunatic whose contempt for women is fueled when he, on behalf of Queen Victoria, as Jack the Ripper murders one prostitute after another. They let Gull be harassed by strange visions inspired by Douglas Adam’s humorous detective story Dirk Gently’s Holistic Detective Agency, which Douglas described as a “ghost-horror-detective-time-travel-romantic-comedy-epic, mainly concerned with mud, music and quantum mechanics.”

In his 1990 Sickert and the Ripper Crimes, Jean Overton Fuller, author of several biographies, singled out Walter Sickert as the misogynistic Jack the Ripper and several authors began to follow her trail.

Obviously, an engrossing interest can easily develop into a phobia. I assume this might happen when imaginative people discover contexts and opportunities where others have not perceived them, people like artists, writers and scientists. It seems that conspiracy theories in particular have an ability to occupy people’s mind sets, discoloring their ideas and interpretation of life.

Patricia Cornwell, who had worked in a forensic lab where she learned the intricacies of forensic investigations, became a multimillionaire through her Kay Scarpetta detective stories, which have sold more than 100 million copies worldwide. The novels about the forensic doctor Scarpetta contain a number of details about forensic methods, which provide solutions to often extremely macabre murders.

By the end of the last century, Cornwall was seized by a mania which meant that she at all costs had to prove that Walter Sickert was identical with Jack the Ripper. It seems as if she, with her autopsy and author background, became overtaken by an obsession forcing her to solve London’s most gruesome murder mystery. Cornwell put her well-founded reputation as a skilled tracking dog at stake in her search for evidence based on interpretations of Walter Sickert’s dark, provocative and elusive paintings.

An approach that makes me remember how I, together with a school class, visited one of Sweden's most well-known forensic pathologists. It was his observations that had led to the capture of a serial killer.

Between October 1978 and January 1979, an 18-year-old relief worker at long-term care unit at Malmö’s Eastern Hospital had poisoned elderly patients with corrosive cleaning agents. A total of 27 patients developed life-threatening symptoms, while 24 of them died in severe pain. The medical examiner explained to us:

I autopsied most of those senior patients. It was pure routine work and, as usual it was a simple matter of determining the cause of death. They had all suffered from severe age-related ailments and many had suffered from far-reaching dementia. In cases like that an autopsy generally recognizes a variety of possible causes of death. In my role as hospital pathologist I am generally not searching for crimes and may thus usually identify “natural” causes of death. However, my suspicions were triggered when an extraordinary number of deaths occurred within a very limited time span, all originating from the same long-term care ward. This awakened the coroner within me and as soon I assumed that there could be a crime hidden behind these deaths I almost immediately found the cause of death. It was so obvious that I could not understand that I had not discovered it before. All the corpses had a strong purple discoloration in the trachea and I could quickly determine that someone had poured deadly detergents, Gevisol, or Ivisol, into them.

The perpetrator was sentenced to “closed psychiatric care” for eleven homicides and sixteen attempted murders. He had been allowed to take care of severely disabled, elderly patients despite having been fired from his previous job as a care assistant at another hospital, with the motivation:

The medical doctor in charge and medical orderlies at the ward have spoken with and about him. He is entirely lacking power of initiative. Acts weird, does not seem to understand what he is being told. Not to be re-employed.

The last sentence was underlined several times.

Patricia Cornwell’s increasingly tenacious efforts to identify Walter Sickert as Jack the Ripper probably has made her blind to other possibilities. Her obsession seems to have led her in the opposite direction to the one generally taken by a criminal investigator. Instead of finding a point of departure based on a chain of clues and events which eventually would lead to a perpetrator, she has from the outset decided that it was Walter Sicker who committed the horrific murders. Cornwell considers his paintings, biography and preserved personal documents as essential clues which binds him to the Ripper murders.

To solve the murder mystery, Cornwell spent part of her substantial wealth to buy no less than thirty-two of Sickert’s oil paintings, as well as a number of his drawings and etchings and a large amount of other “essential Ripper material”.

Cornwell’s fixation on Sickert as a mass murderer has meant that while scrupulously reviewing his works of art she finds nothing else but hints to the murders she believes he had committed. A narrow conception of art that could turn Picasso into a misogynistic murderer.

Not to mention Sickert’s contemporaries among German expressionists, who undeniably had a morbid interest in sexually inspired murders of women and mutilation of their bodies. A phenomenon that has given rise to several special studies.

In addition, Cornwell ignores several characteristics of Sickert's art. She states, for example, that “this artist never painted anything he had not seen”, when he actually used to paint with the help of photographs, postcards and newspaper clippings. Well aware of the fact that public interest was aroused by scandals and crime, Sickert often used ostentatious titles for his painting, alluding to gruesome crimes and sensational news.

When I several years ago read Cornwell's book about Jack the Ripper, I found it to be quiet good, especially her depictions of the misery in the East End and the unrestrained violence against and contempt for the prostitutes of that time.

However, I found that she went too far in her apparently meticulous analysis of Walter Sickert’s assumed character, misled as she was by preconceived notions. Her mistakes are manifold, not least her superficially easy-going analysis of Sickert's peculiar art, which actually is far from being the reflection of a mass murderer’s delusions and/or bad conscience. Likewise, the results of the surveys conducted by generously paid graphologists and DNA experts are not particularly convincing. First, it is uncertain whether any of the carefully researched Ripper Letters, which are filed with Scotland Yard, were actually written by the serial killer. Secondly, Cornwell’s conclusions that the traces of human DNA on two postage stamps correspond to the DNA on stamps found among Sickert’s preserved correspondence. The mitochondrial DNA present on the stamps can be found among one to ten percent of England’s population, i.e. at least tens of thousands of individuals. The same goes for the paper on which several of the Ripper letters were written, although being identical to the one Sickert used this specific stationary was the one most commonly used in England at the time when the letters were written.

Despite this and several other spurious observations, Cornwell stubbornly continues to insist that she is one hundred percent sure that Walter Sickert was identical with the elusive Jack the Ripper, declaring that:

Because if somebody literally proves me wrong not only will I feel horrible about it, but I will look terrible and I will lose my good reputation. […] If it turns out that something indisputably proved that this notorious killer was someone other than Walter Richard Sickert, I would be the first to offer congratulations and retract my accusations.

Unsolved murders often lead to complicated conspiracy theories and if they appear to be politically motivated, those looking for a solution can easily get lost in a labyrinth where unrelated, but sometimes not entirely improbable facts interfere with the investigations, until a quite preposterous pattern emerges.

Just think of the thicket that grew up around the Kennedy – and the Swedish Palme murders, where Occam’s razor rarely has been used: “entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity,” or “the simplest explanation is usually the best one.” Even if 36 years has passed since the Swedish Prime Minister was shot down in open street and the murderer has not yet been convincingly identified, speculations and crack-pot ideas remain endemic.

Personally, I believe in the theory that it was the US citizen Francis Tumbelty who was identical with Jack the Ripper. He was a famous quack with a lugubrious collection of female body parts in his New York home. Tumbelty had traveled extensively throughout the United States and Canada and also visited England. As a shameless and big-lying self-promoter he sold worthless herbal medicines and even performed surgery. Tumbelty became known for reckless dithyrambs against women, especially prostitutes, whom he hated after his failed marriage to a woman who eventually turned out to be a prostitute.

In 1996, former Detective Commissioners Stewart Evans and Paul Gainey published Jack the Ripper: First American Serial Killer, in which they presented evidence that Tumbelty had resided in a Whitechapel guest house during the short period that Jack the Ripper ravaged the East End. He was arrested on suspicion of “gross indecency”, which at the time was the term for “illegal homosexual activity”. Scotland Yard had Tumblety on its list of suspected Jack the Rippers and when he was released on a bail of £ 300, the quack did under false name escape to France, from where he four days later boarded a ship destined for the US. Scotland Yard immediately requested that Tomblety be extradited, but US authorities refused on the grounds that there was no evidence of Tomblety' s involvement in the Whitechapel murders and the crime for which he had been detained in London was not grounds for extradition from the United States. The American authorities completely ignored the fact that Jack the Ripper’s bloody progress ceased completely when Tumblety left London.

Most experts critique of Patricia Cornwell's bestseller Portrait of a Murderer was quite ruthless. An example is Caleb Carr’s review in The New York Times:

Portrait of a Killer is a sloppy book, insulting to both its target and its audience. The only way for Cornwell to repair its damage will be to stay with this case, as she says she intends to, continuing her research, studies and tests for the years required to complete them thoroughly. Perhaps then she can then do what she claims to have done already – prove Walter Sickert’s guilt decisively. Failing that, she should apologize for this exercise in calumny.

For several reasons Caleb Carr was the right man to criticize Cornwell’s book. After several years of study, he was an expert on most of what had been written about Jack the Ripper, as well as the time and environment in which the murders were committed. This is especially noticeable in Carr’s two novels The Alienist and The Angel of Darkness.

The two thrillers take place in New York by the end of the 1890s. The environment is accurately described in great detail. Several celebrities take part in the stories, such as the future president Theodore Roosevelt and the multimillionaire J.P. Morgan. Nasty mass murderers reminding of Jack the Ripper are ravaging the metropolis, though tracked down by child psychiatrist Laszlo Kreizler, the private detective Sara Howard and journalist John Schuyler Moore, who use modern methods such as investigative journalism, fingerprints and forensic psychology. The novels are well-written and constitute a quite exciting reading, and have furthermore become the basis for two excellent TV series.

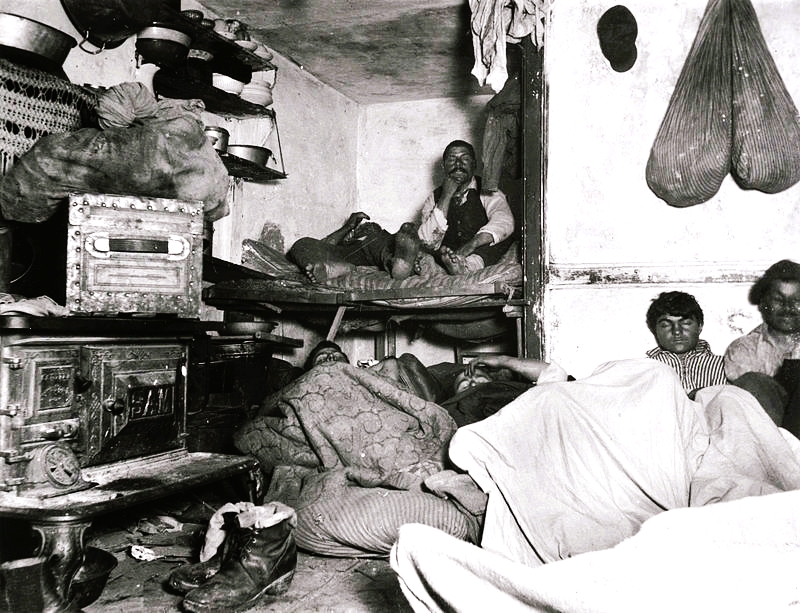

If Jack London's and Gustave Doré's depictions of the misery in the East End provided a frightening depiction of the environment where Jack the Ripper committed his crimes, the Danish-born Jacob Riis’ (1849-1914) detailed depictions of the misery in New York's slums did the same for Caleb Carr's novels.

To bring about social reforms Riis tried to spread knowledge about the terrible situation of the poor. He was one of the first to use photography to document miserable conditions and thus make people realize the deplorable situation of destitute people. The new invention of photo flashes made it possible for Riis to take photos indoors and as a fearless, kind man he was able to move unmolested in lawless areas. In 1890 he published an upsetting, but nevertheless unsentimental and coldly documented social report How the Other Half Lives, richly illustrated with photographs and drawings.

In an interview Carr stated that it is important for him that everything in his thriller is true “except for the story itself.” Especially in The Angel of Darkness, Carr explores the lingering effects of childhood trauma and the destructive violence they might bring forth in their victims.

I had a lifelong fascination with all forms of violence, from war to personal violence, the latter being what I had the most experience with in my life, whether from the troubles with my father or battles on the streets of Manhattan . ... And that interest eventually evolved into wanting to understand the roots of violence.

Through his hero Dr. Kreizler Carr intended to portray how a skilled psychiatrist may gain insight into a murderer’s disturbed state of mind. Kreizler is able to enter the mind of a serial killer, by descending into his own memories and experiences he is able to fathom what controls a killer’s murderous instincts and guides her/his actions. The only difference is that Twizzlers and the killer went their separate ways. Carr created Kreizler by projecting his own personality on him. The author makes no bones about his own mental wounds “there was a lot of madness in my family, a lot of alcoholism among the adults" and he states that this has hurt him for life.

Caleb Carr's father, Lucien Carr (1925-2005) was a key figure in the so-called Beat Movement and especially close friend of Jack Kerouac. Carr knew the unusually mad William Burroughs from his youth in St. Louis. It was actually Carr who introduced the Beat Movement’s most prominent men – Burroughs, Kerouac and Allen Ginsburg – to each other. It has been suggested that Carr was a troubled and mentally unstable young man, nurturing a host of crazy, inventive and downright dangerous whims that fascinated the beat poets. Allen Ginsburg later stated that Lucien Carr was in many ways the center of the entire beat group, at least in the beginning – “Lou was the glue.”

The first time Jack Kerouac’s name appeared in the press was on August 18, 1944, when he and William Burroughs were arrested as material witnesses to a brutal murder. Even if the news of the day before had been dominated by the Allies’ successful landing on the south coast of France, the assassination was sensational enough to appear on the front page of The New York Times: “Columbia student kills friend and sinks body in Hudson River.”

David Kammerer and Lucien Carr had met in St. Louis at a summer camp for boys. The then twelve-year-old Carr was a student and the fourteen year older Kammerer sports instructor. Kammerer had a Ph.D. in English Literature and taught Literature and Sports at Washington University in St. Louis. Carr would later, like his friends and family, insist that a homosexual Kammerer had stalked the handsome Carr, and for the next nine years he had appeared wherever the young Carr found himself.

Much of that story, however, is doubtful. It is almost impossible to unravel the threads of insinuations, legal spins and lies surrounding Hammerer's death. There is no independent evidence that Kammerer actually had been a stalker, only Carr’s own words that it had been the case. However, there is compelling evidence that Kammerer was not gay and Carr often boasted about his ability to manipulate the older man. He even got Kammerer to write essays for his classes at New York’s Columbia University.

In any case, the then twenty-three-year-old Carr did on his own accord go to the police and admitted that in desperation and panic over Kammerer’s homosexual approaches had stabbed him to death with his scout knife. After the bloody deed he had wrapped his victim’s arms with his own belt, weighed his corpse down with stones and dumped it in Hudson River.

By all accounts, the two men had been seriously intoxicated, possibly also under the influence of drugs, and the motive for the murder has remained unclear. It is possible that Carr used Kammerer’s implied homosexuality and alleged stalking to mitigate his sentence. In any case, he was sentenced to twenty years in prison, but was released after two years. Lucien Carr then spent 47 years as a journalist at the United Press International’s (UPI) news agency.

Although Lucien Carr became significantly more established than his beat friends, he continued to hang out with them. His son Caleb found it disconcerting to be close to his father’s erratic friends:

They could be perfectly nice people one-to-one. Kerouac was a very nice man. Allen could be a very nice guy. Burroughs was a little strange for a child. But they weren't children people. You needed to be grown up to be around them if you wanted to not be terrified. What they were up to was not gonna make any child reassured.

Patrica Cornwell also had a difficult childhood. In an interview, she claimed that her interest in brutal murders and forensic techniques was based on childhood experiences:“It’s because I grew up with terrible fear. I grew up in such a frightening manner."

After her father, who was a medical doctor, had left the family and she had been assaulted by a police officer who turned out to be a well-known pedophile, Patricia moved with her mother and two brothers from Miami to North Carolina. There the mother suffered from a severe depression that made it impossible for her to take care of her children. Patricia Cornwell was placed in a foster home where she was bullied and frightened by foster mother. As a teenager Patricia suffered from severe anorexia and was later affected by recurrent depressions and intermittent alcoholism.

Thus, it seems that several detective story writers, and apparently many of those fascinated by Jack the Ripper, have suffered from severe childhood traumas and through their novels tried to conjure up and try to handle their inner demons. But, what about their readers? Several of my acquaintances devour detective stories and for some of them it is the only reading they are engage in.

It does happen that I occasionally read a thriller or detective story, but it is far from an immersive interest. Despite that, this blog post actually testifies that over the years I too have devoted a certain interest to Jack the Ripper. As long as I remember I have had a tendency to scare myself and even enjoying it. Even the Swedish children’ book author Elsa Beskow, whose ingenious and sometimes disturbing illustrated tales have etched themselves forever in my memory. Perhaps most of all the Tomtebobarnen, in English translated as The Mushroom Children, which she wrote and illustrated in 1910. It contained an image of a terrible troll that gave me an unforgettable fright when I first saw it:

An old mountain troll lives in a gorge next door,

the children walk quietly past, when they hear him snore,

cause sometimes it might happen he looks out and hollers “Boo!”

happily scaring the wits out of you.

Then the children rush home in highest speed,

scrubbing knees, while stumbling over tufts and weed.

But the troll bellows and laughs out loud:

“It’s great fun to see that frightened crowd!”

Elsa Beskow (1874-1953) was married to Natanael Beskow, a famous priest, author, artist and school principal. They had six boys, among them the artist Bo Beskow. While her husband was active as a pastor with his own church and later as principal, Elsa Beskow cultivated her art by creating lavish picture books and ingenious stories. She thus accounted for an important part of the household’s income, at the same time as she took care of both home and her writing while her boys were playing around her.

.jpg)

Like his wife, Natanael Beskow was a skilled artist and the talent was apparently inherited by his son Bo. Below we see Bo Beskow’s portrait of his close friend, the UN General Secretary and member of the Royal Swedish Academy, Dag Hammarsköld, next to a still life painted by Natanael Beskow.

.jpg)

Bo Beskow (1906-1989) wrote a charming book about his childhood, Krokodilens middag, The Crocodile's Dinner, in which Jack the Ripper suddenly appears in the otherwise obviously quite harmonious, Beskow home:

The wardrobes contained exciting treasures. In one of them, Father kept immoral literature, which he collected as a member of a committee dedicated to the eradication of such nuisance. My older brothers had found this treasure trove and a lot of extensive reading was done at night, when everyone was officially asleep. Bo was six years old and had just learned to read. Totally engrossed by the thriller Jack Uppskäraren, [“Jack the Slicer” the Swedish denomination for the killer] I took the book down to Sunday breakfast. “What is Bo reading?” I was never able to finish the book and since then tried in vain tried to get hold of it. Who was Jack the Slicer? The mystery has interested many, most recently I found that Blaise Cendrars claimed that his hero Moravagine was Jack the Slicer, which of course is bragging. My childhood hero remains undiscovered. I dare to say that no child lives in what is called a protected world, even if parents and themselves pretend that it is like that. Life becomes predestined by what you learn during the first five intense years of your existence, for better or worse. Even children’s parties and games could be a harrowing experience, especially refined variants of Blindman’s Bluff.

I assume that the book that Bo Beskow had found in his father’s secret e closet was Jack Uppsprättaren, which in 1889 was published with a title that might be translated as “Jack the Slicer: The Story of the Killer of Nine Women within the City of London and a Mournful Song about the Murderous Jack.”

The book was one of the first books published about the Ripper murders. It was written just after the murder spree had come to an end and contained detailed descriptions of the grotesque murder cases, not least new and sensational information about the Swedish victim, Elizabeth Stride. The anonymous author, who wrote under the pseudonym Ansgarius Svensen, was unusually well informed.

That a Swedish book came out so shortly after the Ripper murders is not so strange, considering that a lot of English, speculative books were written within weeks after Jack the Ripper’s disappearance. First of them all was The Curse Upon the Miter Square 1530-888, written by the Catholic and organist John Francis Brewer (1865-1921). This novel was published just a week or so after the discovery of the murdered Catherine Eddowes – Jack the Ripper’s penultimate victim. Brewer’s novel is far from a reportage book, it is a “Gothic” horror concoction about a mad monk who in 1530 murdered and maimed a woman in front of the high altar of The Church of Holy Trinity in Aldgate, a church that once lay in the same place where the murdered Catherine Eddowes was murdered. This spot was apparently considered be haunted and the scene of several other murders. The monk’s victim turned out to be his own sister whom he by mistaken had murdered and eventually dismembered. In spite of his mixture of fantasy and facts, Brewer gives a fairly correct and detailed description of the gruesome findings in connection with the Dowses murder, though he suggests that the restless ghost of the mad monk had a hand in the game.

In 2021, an estimated 437,000 people were murdered. During World War I, 20 million were killed, the subsequent Spanish flu is estimated to have claimed 50 million lives. Between 70 and 85 million people fell victim to World War II. In the Nazi concentration and death camps 6 million Jews, 3 million Soviet prisoners of war and an estimated 500,000 Roma/Sinti were annihilated. In the Soviet Union, between 15 and 25 million people were killed through Government action. The Vietnam War resulted in 3.6 million deaths. The last two wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo and its direct consequences have cost 5.5 million lives. Genocide in Cambodia led to between 1.5 and 3 million deaths, in Rwanda between 400,000 and 500,000 persons were massacred, in former East Pakistan between 300,000 and 3 million, in Indonesia between 500,000 and 1.2 million. In addition to these enormous death tolls have dictatorships and genocide claimed millions of victims around the world. Why are we among all these millions of victims so fascinated by the murders of a few individuals – like the five victims of Jack the Ripper?

Why are mass atrocities not as upsetting as individual murders and so often quite forgotten? One example among tens of thousands – who is today talking about atrocities like those committed by Romanian soldiers in Odessa during two October days in 1941?

The campaign that now ensued against the Jew of Odessa was reported by Germans who witnessed it. That same morning, October 23, nineteen thousand Jews were assembled into a square near the port, which was surrounded by a wooden fence; they were sprayed with gasoline and burnt alive. In the afternoon, gendarmes and the police rounded up over twenty thousand persons in the streets – again most of them Jews – and squeezed them into the municipal goal. The next day, October 24, they removed sixteen thousand Jews from the goal and in long columns they were forced to walk in the direction of Dlnik, a nearby village […] they were bound to one another´s arms and in groups of between forty and fifty they and shot dead. When this method proved too slow, they were pressed into four large warehouses which had holes in the walls. Machine gun nozzles were pushed into the holes, and in this manner mass murder was committed in one warehouse after another […] for fear that that some might escape, nevertheless, three warehouses, which were mainly filled with women and children were set on fire. Those who were not killed killed by the flames sought to escape through the holes in the roof, or through the windows; these were met with with hand grenades or machine -gun fire. Many women went mad and threw their children out of the windows. The fourth warehouse, which was filled with men, was shelled the next afternoon.

When I lived in the Swedish town of Lund and during cold winters looked out of the window over apparently endless snow fields, it happened that I sometimes thought of Göran Sonnevi's poem About the War in Vietnam. How he after a heavy snowfall in the morning goes out and shovels snow outside his house in Lund and then thinks:

The dead are numbers, they lie down, whirl

like crystals in the wind over fields. Up till now

they figure 2 million have died in Vietnam.

Here hardly anyone dies

except for personal reasons. The Swedish

economy doesn’t kill

many, at least

not here at home.

Maybe there is a connection with the man at Niehaus’ IKEApaintings. When the dead become too many, they are abstracted as the man among IKEA's constructed home environments. Reality becomes diffuse, constructed and difficult to understand.

I am reminded of a painting by Lorenzo Lotto – Michele arcangelo caccia Lucifero, The Archangel Michael Chases Lucifer, from 1545. If we look closely at that painting we find that the angel and the devil are the same person.

Begg, Paul och Martin Fido (2015) The Complete Jack The Ripper A-Z - The Ultimate Guide to The Ripper Mystery. London: John Blake Publishing. Cadwalladr, Carole (2025) ”Patricia Cornwell: ’I grew up with fear’”, The Guardian, November 1. Carr, Caleb (1994) The Alienist. New York: Random House. Carr, Caleb (1997) The Angel of Darkness. New York: Random House. Cornwell, Patricia (2002) Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper Case Closed. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. Gainey, Paul och Stewart Evans (2013) Jack The Ripper: First American Serial Killer. New York: Random House. Garner, Dwight (1997) ”Interview with Caleb Carr”, Salon, October 4. Gilbert, Martin (1987) The Holocaust: The Jewish Tragedy. London: Fontana/Collins. Homberger, Eric (2005) ”Lucien Carr: Fallen Angel of the Beat Poets, Later an Unflappable News Editor with United Press”, The Guardian, February 9. Knight, Stephen (1979) Jack the Ripper: The Final Solution. New York: HarperCollins. Knight, Stephen (1988) The Brotherhood: The Secret World Of The Freemasons. London: Grafton Books. Lilly, Marjorie (1971) Sickert: The painter and his circle. London: Paul Elek Publishers. Moore, Alan och Eddie Campbell (1999) From Hell. Marietta, GA: Top Shelf Productions. Riis, Jacob (1997) How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York. London: Penguin Classics. Sickert, Walter Richard (1910) ”The Naked and the Nude,” The New Age, 21 July. Sonnevi, Göran (1982) The Economy Spins Faster and Faster. Translation from Swedish by Robert Bly. Pawcatuck CT: Sun Publishing. Tatar, Maria (1997) Lustmord: Sexual Murder in Weimar Germany. Princeton University Press.