LA BELLA FIGURA: Looks and behaviour

With good reason it happens quite often that my generally chic and fashion conscious wife complains about the way I dress, as well as my general appearance. Just before we are going out together she tends to give me an apologetic glance and point out that I am dressed like a hobo and that my hair sprawls in all directions "like it does on that mad professor in Back to the Future."

She's right, I am actually enjoying being well-dressed, but sometimes I lack clean, ironed clothes, combined with the fact that during a number of years I have not, out of sheer laziness, renewed my wardrobe; shirt collars and cuffs are worn, my costumes are dingy, pants are stained and my socks have holes. I am careless while shaving, not always sprinkling myself with fragrance and cut my hair far too sporadically. Actually, I am quite convinced that there must be some truth behind the expression that "clothes make the man." Even if I may be blind to my own shortcomings, I pay attention to how others dress, behave and smell. With wonder and horror I remember the old men's scent that struck me when I in my youth worked in mental institutions or visited elderly persons in their lightly cleaned and poorly ventilated apartments.

Looking at myself on photographs I cannot fully understand that the old, wizened, thin- and white-haired man, actually is me. Maybe my natural odour has now become similar to the one I abhorred among the old men in nursing homes. Do I have the same dishevelled and unhealthy look? Looking at myself is like when I hear my own voice. Do I really sound like that? I thought my deep baritone was quite appealing, but it isn´t and inside my withered shell I feel no older than thirty years. Maybe the irritating feelings about my looks are amplified by a lack of the concern about them that most Italians around me, young and old, expose by always being well groomed and smartly dressed.

Such notions were brought to life once again when I some time ago saw the movie Saturday Night Fever. It was better than expected, it was almost forty years ago the last time I saw it. In the opening scenes we meet Tony Manero, the character played by a twenty-two years old John Travolta, n acto that is actually born the same year as I, spending his working days in a hardware store, or at home in his parents´ meagre, but stuffy house, where he has his bedroom decorated with posters of Bruce Lee, Sylvester Stallone and a young Robert de Niro. On weekends Tony transforms into a dapper dandy with razor-sharp creases on his white, slimmed trousers, wearing a winning smile he confidently sports a spotless, dazzling white Three Piece Suit, partially exposing his hairy chest under a black silk shirt and several gold links. The undefeated king of the dance floor, a dream and eye-catcher for enchanted, young ladies. Tony Manero appears as a prototype for an Italian Bella Figura.

The words mean “beautiful figure”, though Italians attach a much richer meaning to the expression. In a dictionary I find the explanation "to make a good impression" a concept associated with both visual and inner qualities - how you look, and behave, how to win admirers and impress your surroundings. It may occasionally appear as if the effort to charm the people around you is appreciated almost as much as the actual result.

I guess that Italian culture is endowed with a significant element of hedonism; enjoyment of life and beauty, a search for aesthetic perfection - in music, art, design; how a suit is cut, flowers arranged, the shape of a car, colour combinations on a house facade, the composition of a culinary dish, the angles in a movie, or a photograph. I remember how a Jewish friend of mine, the writer Esther Hautzig, once told me: "We Jews have or scriptures and books, we are a people of stories, but the Italians are the great aesthetes, the supreme artists. They have the visual arts, we have the word." Similarly another friend, who had converted to Catholicism, noted: "I tell you, Jan, that compared to Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism is like Swedish knäckebröd, crispbread, compared with Danish pastry." I think they both were quite right, there is in Italy a baroque, full-bodied opulence, an enduring aesthetic commotion.

The youthful Karol Józef Wojtyła, alias Pope John Paul II, was in many ways an incarnation of La Bella Figura and thus immensely popular among many Italians. When he in 1978, fifty-eight years of age became the head of the Catholic Church Wojtyła was a handsome man, with a background not only as a spiritual guide, but also as an actor and able football player. He was in radiant good health; jogged in the Gardens of the Vatican City, hiked in the Italian Alps, lifted weights and swam. I appreciated his struggle against Communism, but was influenced by what some of my Latin American Jesuit friends told me between four eyes - that the Pope had a steel fist in a silk glove.

When I several years ago met him in La Paz, Father Xavier Alba shock his head and told me: "This Pole that now occupies the chair of Saint Peter, does not at all understand what so many of us Latin American priests are fighting for." Obviously, John Paul II was no friend of Latin American liberation theology. When Bishop Óscar Romero, who was mowed down by machine-gun fire while celebrating mass in a hospital chapel in San Salvador, had visited the pope in Rome and asked for the Church's support against Salvadoran death squads, he got a flat refusal. Nevertheless, the martyrdom of the bishop apparently affected the pope and he bestowed the title of Servant of God upon the dead Romero and a cause for canonization was opened for him. When the radical priest and poet Ernesto Cardenal knelt to kiss the Pope's hand in Nicaragua John Paul took it away, waving his finger at him and said: "You have to sort out your position with the Church." Recently I came across a picture of my Jesuit friend Xavier Albo, he wore a T-shirt that read I Love Papa Francesco. He finally got a Jesuit brother with the proper views on the papal throne.

John Paul II was a charming and powerful representative of a struggling Church. With his shortcomings he was "a Pope of his time", who after having lived through two assassination attempts, the last one he survived as by a miracle. Four gunshots hit him from close quarters; two in the abdomen, one in his right arm and another shattered his right little finger. One of the bullets buried deep in his abdomen could not be removed. John Paul II recovered and continued to travel around the world. He was ecumenically minded and as the first pope ever he even visited a mosque, he chose the magnificent mosque in Damascus. Large crowds hailed him wherever he appeared. I saw him several times. His aging was merciless, with severe breathing difficulties, while Parkinson's disease made it difficult for him to speak and severe arthritis gave him a painful, staggering gait. Nevertheless, almost to his last breath John Paul II continued to be seen in public, with obvious pain and slurred speech.

Toward the end of John Paul II's life I and Rose's found ourselves on St. Peter's Square when he to an outburst of general exaltation appeared in one window of the papal apartments to greet the crowd. He was bent and looked very weak, his garbled speech was reinforced by the loudspeakers, but I could not grasp a word of what he was saying. Then a nun turned to me with beatific smile, tears running down her cheeks. Deeply moved she said,: Que Bella Figura! Que Bella Figura! At that moment I understood the true meaning of the words. The immense respect that the nun felt before this pain broken, stammering old man who had dragged himself up before his flock of devoted admirers. Incredulously I repeated her words: Que Bella Figura? The nun grabbed me gently by the arm, leaned toward me and said: "Behold that man. How he with all that pain and obvious physical decline dares to show himself before us in all his human frailty. What stature! What bravery! What faith! Que Bella Figura."

Another surprisi and completely different interpretation of the notion of Bella Figura was given to me by a friend of mine who spoke appreciatively about Berlusconi's face lifts, his oily, black coloured and implanted hair and his exaggerated facial makeup. My friend noted that he had not appreciated this clever, but villainous and manipulative politician, but it was a different matter with his winning smile, perfect costumes and outrageous statements.

This guy really knows how to behave. He is furbo [smart] out to his fingertips. He knows what people want, he plays them like a piano. And this with his latest hair implant, is it not amazing that he dares to admit what he has done so openly? He proves that he is making his utmost to make a good impression. It is quite different from all other participants in the danse macabre of Italian politics. Il Cavaliere [“the cavalier”, an epithet that Berlusconi's supporters like to use about him] is for sure a Bella Figura.

All that made me dive down into what I imagine are some aspects of the Italian concept of beauty. As so often before, I began with the word. The Italian bello apparently originates from the Latin bellus, which meant "sweet, handsome and charming," but the term was used only in connection with children and women. If used about a man the ancient Romans understood bellus to be an insult, an allusion to "unmanly" behaviour, related to the Greek expression καλός, kalos, which was used to indicate that something was of good quality, but also being "sweet". There seems to have been a connection between affectation and bellus/kalos, though both words could also be used about natural splendour, and somewhat later about something that was “well made”, in the sense of a skilful imitation of nature, or even more refined - an "improvement" of nature, which could be done through bodily change, makeup, clothes and mannered behaviour.

Throughout all time periods and in all forms of societies, people have demonstrated an urge to change their looks and adorn their bodies, sometimes in an extravagant manner. Thousands of years back in time, we find among different peoples a variety of methods intended to enhance beauty. For instance, ancient Egypt's upper class women and men enjoyed a morning dip in flower-scented water. They scrubbed themselves with soap made of a mixture of soda and oil. Natron was used to polish the teeth and rinse the mouth. Egyptians also manufactured something they called “soap rock”, clay boiled to remove various minerals and then enriched with fragrant oils.

Wealthy women applied dyes all over their bodies trying to create a golden hue. Veins glimpsed on bosom and temples were considered a sign of beauty and could be painted with narrow, bluish streaks. Eyelids were painted with different hues manufactured from malachite, turquoise, terracotta and coal. Eyes were outlined by narrow streaks "to give them life," the ideal shape was that of a fish, a "lively" animal. A peculiar device among Egyptian beauty accessories was a perfumed "cone", which was placed on top of curly, black wigs, when this cone began to melt it spread fragrance over both wig and face.

Centuries passed in review, demonstrating a continuous interaction between naturalness and artificiality. The pursuit of pleasure, beauty and good living was by severe philosophers and theologians considered to be a treacherous trap that corrupted and ultimately would destroy mankind. To benefit both ourselves and our fellow men we should all ideally live in a measured and constructive manner. However, other thinkers taught that during our short life it was our duty to enjoy grace and beauty. Why waist our precious time on austerity and discipline? Especially if we were fortunate enough to be endowed with an ability to appreciate the joys of life? Each epoch has offered luxury, beauty and enjoyment to affluent classes, while others generally had a quite miserable life, though even the poor adorned themselves in different ways.

Many beauty enhancing practices have been cruel and incomprehensible. Like the Kayan people of Burma among whom some women obtain "giraffe-necks" by having girls from the age of five carry copper rings around their neck in such a way that it slowly expands until it is extended to an unnatural length. If those rings are removed the neck brakes. Or the painful Chinese practice of binding small girls' feet in such a way that their growth was hampered and became "lotus feet". Upper class ladies with such feet could neither walk nor work as other women, a sign of their high status. Several Chinese regimes tried unsuccessfully to ban the practice, while others favoured it and the despicable practice did not disappear completely until the beginning of the last century. Several people have in different parts of the world also engaged in "skull deformation" by applying various techniques to force children's skulls to grow in a specific way. This was a common practice among several groups of Native Americans, including among Mayan upper classes.

Such practices are undeniably cruel and grotesque. However, people trying to change their bodies and thus turn into belle figure is not at all uncommon in our times, where technological advances have enabled plastic surgery to be used to change appearance in such a way that it appeals to those who have undergone the procedures, or who consider them as means to counter the effects of natural aging. People may easily become addicted to such procedures and suffer them at regular intervals, not least Sweden's queen, who almost once a year put herself under the knife. Eventually such routines may become such a bad custom that their practitioners do not even notice how the operations are turning their faces into grotesque masques.

This makes me think of Terry Gilliam's movie Brazil from 1985, a film that, like Matrix, several years later made me consider life with new eyes. In Brazil, people are trapped in an artificial world and a scene etched in my memory is the one where the protagonist Sam Lowry's wealthy mother receives him in a private beauty salon where a strutting doctor is changing her appearance. Like a mixture of hairdressing and surgery he stretches out Mrs. Lowry´s facial skin and then wraps it up with a transparent plastic sheet, while carrying on with soothing small talk assuring his client that the treatment will make her twenty years younger. At a party to celebrate Mrs. Lowry's new "youthful" appearance, a colleague tells the plastic surgeon that his methods are outdated and that Mrs. Lowry's face will soon be disfigured. Unfortunately, an equally rich and superficial lady like Mrs. Lowry, who has undergone surgery by the competitor, suffers a graduate disintegration while parts of her face are distorted, or fall off.

Gilliam now seems to be some kind of prophet, at least when it comes plastic surgery that was not yet in vogue when the film was made. Gilliam's manner of portraying a dysfunctional future has inspired many followers. His future world appears to be very English - men are wearing well-tailored suits, long coats and hats. It is a class society with wealthy people living away from crime infected slums, where poor people are crowded in run-down, inhuman, concrete colossi, while glamorous glitterati engage in shameless consumption. Impersonal power hides behind an oversized, bewildering bureaucracy, watched over by armed guards and armoured vehicles. Everywhere there are strange machines giving an archaic, overly complicated impression and constantly breaking down, or run uncontrollably amok. In accordance with the British chutzpa at its best, Brazil is an elaborate piece of art (albeit somewhat uneven), seasoned with irony and black humour. A mixture of German-Russian expressionism, cinema noir, Monty Python, Chaplin and Kafka. More than with a distant future, Brazil presents us with a contrived and distorted parallel world.

In art, appearance-altering interventions do often not only become an aesthetic means of expression, but also political and culture-critical manifestations. The French artist Mireille Suzanne Francette Porte, who nowadays calls herself ORLAN (always with capital letters) and resides in Los Angeles, began early on to experiment with different forms of body art - she tried different, distorted ways of moving around, manipulated photographs and films, applied various tricks that intended to unite the organic body with the machine, until she in the early 1990s began to call herself Saint ORLAN and engaged in what she called "carnal" art. Through various surgeries she declared that she was going to transform her body and face into a "work of art". Her goal was to obtain cheeks like Botticelli's Venus, a nose like Jean-Léon Gérôme´s painting of Psyche, lips like those of Francois Boucher's Europe, eyes like Diana´s on a painting from the Fontainbleau School and a forehead like Mona Lisa´s. It is doubtful whether the final outcome corresponded to her high expectations.

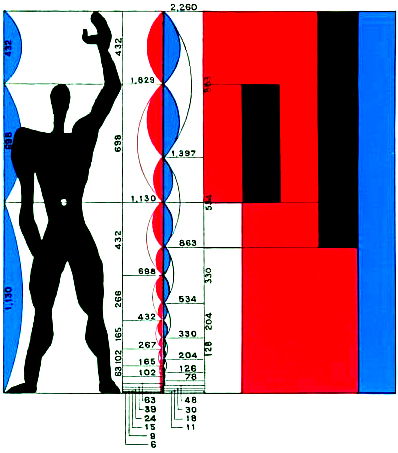

Unlike ORLAN, several Renaissance artists intended not to change nature but wanted instead find a key to its perfection. They rediscovered ancient Greek speculations about mathematics and beauty. They wanted to apply harmony and strict order to architecture, art and even representations of the human body. Everything was thought to be related and they searched for the perfect context of divine proportions. They measured, compared, calculated and constructed. Ingenious artists like Dürer and da Vinci compiled rules for perfectly proportioned human bodies and tried to relate them to different architectural contexts. A quest that in modern times were continued by, for example, the influential architect and artist Le Corbusier.

Several artists and philosophers believed that absolute beauty could be found anywhere in nature and felt that our libido was the compass we ought to follow in our search for perfection. If we found absolute beauty, we could perhaps find God as well. The Italian poet Agnolo Firenzola noted in 1578 in his Dialogo delle belleze delle donne, "On the Beauty of Women” that

… a beautiful woman is the most beautiful object one can admire, and beauty is the greatest gift God bestowed on His human creatures. And so, through her virtue we direct our souls to contemplation, and through contemplation to the desire for heavenly things. For this reason, the beautiful women have been sent among us as a sample and foretaste of heavenly things, and they have such power and virtue that wise men have declared them to be the first and best object worthy of being loved. They have even called her the seat of love, the nest and abode of love, of that love, I say, which is the origin and source of all human joys.

Of course, many women have aspired to equal a reflection of the divine. Some in order to attract men to favourable marriages, others were prostitutes looking for customers. If these women did not entirely match the ideals of perfection, there were various tricks they could resort to. Probably as a result of an assumed correlation between the white colour, purity, beauty and divinity, beauty ideals of the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the Baroque tended to be coupled with whiteness, like smooth, lightly blushing womanly complexion and blond hair.

During their washing ceremonies it was common for wealthy or high-born, Italian ladies to scrub their skin in their quest to obtain a hide as white as possible and to that end they used finely grounded coral sand, resin from the dragon tree, white wine vinegar, various types of pulverised bone and apricot kernels, mixed with cinnamon and honey. They also powdered their bodies with substances, which could include anything from potassium carbonate to arsenic. They bleached their hair with a variety of chemical compounds and it was common for women to wear wide-brimmed hats that left their hair free while their white faces were protected from the sun. Vain ladies slept with their hands covered by gloves prepared with honey, mustard and bitter almonds, in the morning they washed with rainwater and anointed themselves with benzoin ointment.

Such beauty rituals were far from being limited to women, even wealthy and propertied men had an aptitude for various beauty regimens, and then, as now, it was common to assume that elegant costumes and cosmetics could hide their aging bodies´ decay.

Until the late 1700s wealthy, vain men powdered their faces, painted their lips and there existed strict rules for colouring the cheeks as unobtrusively as possible. Both men and women wore different kinds of wigs, dusted with fragrant substances. Many went to extremes. Behind the backs of the aging Cardinal Mazarin it was whispered how he laid on far too thick layers of makeup to hide his advancing age and the French Henry III was considered a ridiculous figure when he exposed himself "made-up like a prostitute" with white-powdered face, with shades elevated by saffron and rouge, while his hair was covered by a specific violet, scented powder.

It sounds extreme, but that people ridicule themselves by trying to apply makeup to cover up their age has probably been common in all ages. My wife remembers how shocked she became when she as a child saw the Dominican dictator Trujillo and discovered how much make-up he had applied to his face – red lips and rouged cheeks. It is also obvious to everyone that Berlusconi is a bit too generous with facial creams and other “rejuvenating” tricks.

Of course makeup and clothes emit sexual signals and a young, blossoming woman with discreet applied makeup may stimulate the desire of a philanderer. Giacomo Casanova wrote that although he hated excessive wear and cosmetics applied to hide fading beauty, he nevertheless avoided to to seduce an unembellished and badly dressed woman:

What I found extraordinary, and what pleased me greatly, was the excess of rouge, applied in the manner of the court ladies at Versailles. The charm of these painted cheeks lies in the negligence with which the color is applied. It is not intended to appear natural, but rather to please the eyes, which see in it the signs of an intoxication that promises abandon and the transports of love.

During Casanova´s lifetime artificiality and "sophistication" became increasingly questioned by people who craved for a return to all that was natural. In England, gardens and parks were created in such a manner that they would give the appearance of being "real" nature, wealthy women freed themselves from their layers of clothing, corsets and complicated wigs, began breast-feeding their own children and took long walks in the countryside. Openness, simplicity and honesty were being praised and expected to be revealed in people's behaviour, stressed by simple clothes and an undisguised exposure of honest expressions.

Philosophers and scientists became interested in how emotions could be reflected through body language and facial expressions. Many felt that it was wrong to try to hide their feelings. It was better to give free rein to joy, anger and sadness. It was no longer contemptible for a man to cry. It was assumed that an essential part of an upright person's true nature was to openly reveal to others how s/he felt. The large amount of facial muscles were proof of this.

Between 1775 and 1778 the Swiss physician Johann Kaspar Lavater did, in collaboration with Goethe, write four volumes of his influential Physiognomische Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntnis und Menschen Liebe “Physiognomic Fragments to promote Knowledge about Human Nature and Human Love". Thus Lavater introduced what, according to him, was a scientific approach meaning that a through a systematic study of the posture, specifics of the body and more or less conscious facial expressions could reveal the character and inclinations of a human being. The mind shapes the body and vice versa, thus generous makeup, overly elegant clothes and affected behaviour were not only false, but reprehensible. Being endowed with a Bella Figura ceased to mean a person´s adherence to established ideals of beauty. Harmonizing your looks and behaviour with other people's desires and expectations was assumed to be an indication of being both false and insecure.

Such thoughts soon gained importance in art and fashion. Leading woman artists like Louise Vigée-Lebrun and Marie-Guillemine Benoist began to present themselves in intimate and loving relation with their children and put on négligés - elegant, thin airy dresses draped over the body. Men and women ceased wearing wigs and makeup, like in all times, however, there were also those who in protest clinged to the old fashion, and some even began to exaggerate artificiality.

Even the absence of makeup could go to extremes and within bohemian circles it became increasingly common to exaggerate emotions, and even shortcomings, weaknesses and diseases. The English philosopher and social critic Edmund Burke had in 1786 in his A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful discussed the concept of beauty and found that it was far from the ideal of Greek Pythagoreans, speculative Renaissance philosophers or French academy members. According to Burke, beauty was not only found among phenomena that could be calculated in accordance with a logical framework. Instead, it could be quite the opposite - what appear as beautiful could also be found in the wild; the uncontrolled, the incomprehensible and exotic. Yes, in some cases even the cruel and frightening can be considered beautiful.

Passion and admiration caused by the untamed, or what Burke preferred to denote as the “sublime” nature, appeared to be the most powerful, and emotions caused by unaffected nature were generally conditioned by some degree of horror, since horror comes from something we cannot control, or even understand or expect:

Astonishment, as I have said, is the effect of the sublime in its highest degree; the inferior effects are admiration, reverence, and respect.

Now violent storms, steep mountains, deep oceans, and wildlife rushed into literary works and sophisticated soirées. No longer was enlightenment and harmony considered chic and beautiful, light craved its shadows. Movement, the unexpected and uncontrollable passion gave depth to existence and increased aesthetic enjoyment, gave relief from the tediousness of everyday life. Imagination, dreams, and unbound creation were dazzling and adorable. Without darkness no light, no night, no days without grief, fear and longing, joy demanded its opposite.

Aesthetic delight was not dependent on any mathematical rules and neither was love and passion. Life had its dark, unfathomable depths, where death, suffering and disease were looming, their threats and proximity might even enhance our pleasure, the unfathomable bliss of the moment. The bright white might be synonymous with the divine, but could just as well be a premonition of death. Like the hectic fever roses on a tuberculosis sufferer's deathly pale face. A combination of light and dark, white and black, life and death were suddenly in vogue.

Blonde hair was no longer an ideal of beauty and was replaced by the black. An open blue gaze gave away to unfathomable, deep-set eyes. Gone were the voluptuous ladies of the Baroque and Rococo, with their tender flesh exposed in lush gardens or among satin, silk and lace, inside intimate boudoirs. Now men and women controlled their weight by drinking vinegar and lemon juice, avoiding meat and fat. Several bohemians experimented with hallucinogenic drugs, turned days into nights while indulging themselves in dreams and imagination in "artificial paradises" of art and intoxication. Women read late into the night in search of the dark circles around the eyes, which were considered a sign of mysterious beauty.

Susan Sontag wrote in her masterful essay Illness as Metaphor that even the dreaded tuberculosis could be perceived as "sublime", with its heated feverishness in proximity of death. Tuberculosis was considered to bestow an "ethereal" appearance and the disease was also believed to stimulate creativity. Aesthetes seemed to ignore the sickening stench from infected lungs that wrecked the breath of ailing victims and instead described the course of the insusceptible sickness as a drama undulating between deathly paleness and fever rosy complexion, paired with hyperactivity that suddenly could be converted into deep lethargy. How the body faded away until it seemed to be almost transparent, while anxiety and fear of death´s relentlessness gradually were replaced by stoic calm and resignation. Sontag gives a number of famous examples of "romantic" depictions of TB patients last moments.

However, even the pale, doomed ideal of women could turn into its opposite. A bold artist could just as well become attracted by an ”Amazon", embodied by a liberated woman writer like George Sand, who by her friend Marie d'Agoult was described as

an excellent hunter and amazon, with whip in hand, spurs on the boots, rifle over her shoulder, a cigar between her lips, a glass of wine in the hand, the subject of gossip and scandals.

The men surrounding a woman like George Sand also appeared as enticing and exotic. Several of theme belonged to the group of free spirits who called themselves “bohemians”, people from Bohemia, a term commonly used to denote the Romani people. By calling themselves Bohemians free-spirited artists wanted to demonstrate that they were independent filibusters far removed from oppressive bourgeois conformism. They dressed and acted their part to emphasize their singular personality. Some of them did not even pretend to be odd, they gave from the start an exotic and alluring impression. Archetypes were the death marked violin virtuoso Paganini, or the astoundingly talented pianist Ferencz Liszt, who in his Hungarian homeland early had been fascinated by the Romani people:

Few things fire our imagination more in early youth than the glaring enigma of the Bohemians, begging a miserable coin before every palace and cottage in exchange for a few words murmured in the ear, a few dance tunes which no wandering fiddler could ever imitate, a few songs for setting lovers aflame, but not invented by lovers. […] this charm to which everyone fell victim, but which could not explain it.

Dressed in black, with his long hair, his profile of a raptor and passionate piano playing, Liszt captivated his audience. His piano playing was said to be able to lift a many-headed audience to unprecedented levels of mystical, musical ecstasy, while Paganini's violin playing gave birth to a legend he had entered a pact with the Devil, a rumour that even caused problems surrounding his funeral – was he really a true Christian?

Admirers swarmed constantly around Liszt and violently fought over handkerchiefs and gloves he had left behind. His fans carried his portrait as brooches and cameos, for everyone to see who their idol was. Armed with scissors women crept upon their boundlessly admired piano virtuoso, to cut a lock of his hair. If a piano string snapped during one of Liszt´s concerts groups of excited women rampaged on the stage to rip it off to make a bracelet out of it. The lucky ladies who happened to attend any of Liszt´s café or salon visits brought with them small glass phials to preserve the coffee swigs he left behind. Women fainted during his concerts and had to be carried out, while police and guards were ordered to protect the musician. The poet Heinrich Heine dubbed this mass psychosis Lisztomania and it would not be repeated until a hundred years later by the even more passionate Beatlemania. A journalist wrote:

Liszt once threw away an old cigar stump in the street under the watchful eyes of an infatuated lady-in-waiting, who reverently picked the offensive weed out of the gutter, had it encased in a locket and surrounded with the monogram "F.L." in diamonds, and went about her courtly duties unaware of the sickly odour it gave forth.

That story made me recall a radio programme I listened to in 1998 in which the Swedish actor Thommy Berggren told the listeners that when he lived with his wife Monika Ahlberg in Hollywood his agent called him to inform that Frank Sinatra, Thommy´s idol, was sitting alone at the bar of Chasen's restaurant. Berggren and Monika rushed away to Chasen's, but Sinatra could not be found anywhere. Berggren ordered a drink from the Italian bartender and entered a conversation about Frankie.

- But he is here right now, exclaimed the bartender. He just went to the loo.

The Swede and his wife just had to sit by the bar and Sinatra would for sure be there in a minute or two and he would probably like to speak to the Swede, especially if he was in the company of such a beautiful lady. Berggren asked what Sinatra used to drink

- Always whiskey. Jack Daniels. There he is! whispered the bartender and nodded in the direction of the exit.

Berggren caught a glimpse of his idol on the way out, he wanted to run after him, but Monika grabbed her husband's arm:

- Calm down, please! and Frankie disappeared.

- Damn it! Berggren thought as the bartender pointed to the ashtray:

- That was a pity, so close for you. Look, there lies his cigarette.

Thommy Berggren stared at the ashtray by his side, where thin smoke was still rising from a Chesterfield cigarette. Monika saw her husband's loving gaze at the butt and wondered ironically;

- Should you not take a puff? before she headed to the toilet

When Monika had disappeared, Berggren quickly ordered a double Jack Daniels

Then I gently lifted Sinatra´s cigarette and took a long, deep inhale, washing it down with a giant swig of Jack Daniels, while I closed my eyes.

The appearance, looks and clothes women and men endowed with bella figura have always been admired and copied. It is said that Goethe's novel The Sorrows of Young Werther made many young men who had been unfortunate in love, to walk around in a blue dress coat and yellow vest. It has even been stated that like the fictional hero some of them committed suicide. Elvis, Hemingway and Marilyn Monroe have thousands of imitators and lookalikes, Jim Hendrix and Audrey Hepburn were trendsetting fashion idols. Examples are countless.

Of course, fashion designers have had a huge influence on what had to been done in order to appear as a bella figura. It is said that it was Coco Chanel who in the early twenties, by abolishing umbrellas and gloves, took away women's fear of sunshine. Soon it became a prevailing ideal for both women and men to be tanned and fit. Trends come and go. We are constantly changing, perhaps without even noticing it. Fanatical, or frightened, Japanese soldiers who after decades appeared again among their fellow citizens, after being isolated in islands of Indonesia and the South Pacific, did not understand much of what they met in their homeland - the people were longer, spoke differently, were strangely dressed and, above all, had completely changed their opinions and behaviour.

La Bella Figura may also be related to an elusive, powerful emotion that may arise if we are gripped by an aesthetic shock. Something so beautiful that we are completely overwhelmed, unable to speak and describe our feelings - it can be a beautiful woman that has taken hold of our mind, a magnificent landscape, a work of art, or a piece of music. There is even a name for this affliction – the Stendahl Syndrome, named after a passage in one of Stendahl´s books Rome, Naples and Florence: 1826, where the author explains what happened to him in the church of Santa Croce in Florence:

There lay Machiavelli's tomb, and next to Michelangelo, rested Galileo. What an astonishing collection of men! Looking on Volterrano's Sibylline frescoes, I experienced the most intense pleasure art has ever bestowed upon me. I was in a sort of ecstasy, absorbed by the contemplation of sublime beauty ... I had reached the point of celestial feeling ... As I emerged from the porch of Santa Croce, I was seized with a fierce palpitation of the heart; the wellspring of life was dried up within me, and I walked in constant fear of falling to the ground.

Could it have been something like that the nun felt there in St. Peter's Square, as she admired John Paul the Second´s Bella Figura?

Burke, Edmund (2013) A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. Cincinatti: Simon & Brown. Casanova, Giacomo (2002) The Story of My Life. London: Penguin Classics. Firenzola, Agnolo (1992) On the Beauty of Women. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. O´Bryan, C. Jill (2005) Carnal Art: Orlan´s Refacing. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Paquet, Dominique (1997) Miroir, mon beau miroir. Une histoire de la beauté. Paris: Gallimard. Rostand, Claude (1972) Liszt. London: Calder and Boyars. Stendahl (1987) Rome, Naples et Florence: 1826. Paris: Gallimard. Sontag, Susan (2009) Illness as Metaphor and Aids and Its Metaphors. London: Penguin Classics. Walker, Alan (1987) Franz Liszt, the Virtuoso Years (1811 – 1847). Ithaca: Cornell University Press.