MEETINGS WITH FACES: A museum without walls

While spending some time in Prague as babysitter for my-half year old granddaughter Liv, it sometimes happens that I end up gazing into her intense blue eyes. She cannot speak and barely crawl, but smiles happily and openly, something that makes me warm inside. Her eyes have a peculiar brightness, suggesting something I cannot understand and make me wonder what goes on in her child's brain.

Each face is a mystery, my own makes me confused. What it does say about me, to me? Do I really look like that? Am I so old and worn? What´s behind the façade? Can others judge me by it? It appears that a photograph is more honest than a mirror. I imagine myself better looking in a mirror than in photographs.

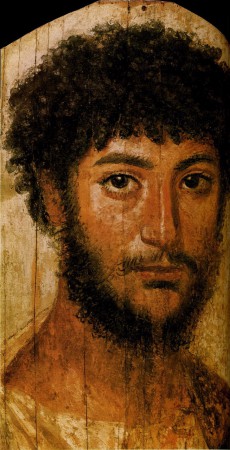

When I look at Liv´s enigmatic, beautiful and expressive face I remember how I twenty years ago visited an impressive exhibition in Rome It was called Misteriosi Volti dall 'Egitto, “Mysterious faces from Egypt”. Mummy portraits from the oasis of Fayium were exhibited within black painted halls. All portraits were placed at eye level, being separated exactly the same distance apart from eachother. Each face was lit in a manner that made it stand out from the surrounding darkness. Looking at such a portrait was like standing face to face to a person who had existed two thousand years ago. Several portraits were eerily alive, as if made for the eternity. Throughout the centuries and in the gallery's dark silence they spoke to me, though what they told me was as indescribable as Liv´s gaze.

The portraits were painted between the first century before and the third century after Christ. They are virtually all that is left of a virtuoso portrait painting tradition that was once was common all around the Mediterranean, though many have argued that it did survive through icons in Orthodox and Eastern Christian churches, indicating similarities between the mummy portraits and, for example, an icon like Christ Pantokrator, which was painted in Constantinople sometime during the fifth century and donated to Saint Catherine's Monastery in Sinai.

There are approximately 900 preserved mummy portraits. They were painted with wax or tempera on wooden plates and attached to mummy wrapping. There are several theories about their origin. Since they all have distinctive and realistic features, some researchers have assumed that the portraits were painted from live models and might have been placed in their homes until the portrayed person died and brought the painting with her/him into the grave. This theory is apparently contradicted by the fact that the persons are portrayed at different ages. Several of them are children, while others are elderly persons. Why would you choose to portray them at a certain age? More plausible is that they were portrayed at the age of their deaths.

Since the faces on the wooden tablets are depicted in their natural size it has been assumed that they were carried in funeral processions and then attached to the mummies. None of this can be proven, but the fact remains - the portraits convey an enigmatic presence and each of them depicts a particular individual, who with wide open eyes is looking directly at us.

I visited the exhibition several times and on each occasion I was amazed by these faces that appeared to seek contact with me across elapsed centuries. When I tried to explain this feeling to an acquaintance of mine, an archaeologist who at the time was working at the Swedish Institute in Rome, she became upset and annoyed:

It is exactly these kinds of exhibits that make me so annoyed. To exhibit those portraits completely out of their context seems to me as a kind of cheap showmanship. The curators are trying to make us believe that those ancient Greek-Egyptians were the same kind of people as we are nowadays. They were not at all like us. They were completely different. They lived and talked differently. Their thoughts were different. We have nothing in common with them, except the obvious fact that they were humans. That exhibition is misleading, unreliable and speculative.

I could not understand her outrage. Was it wrong to identify with people who lived several centuries back in time? Were they really so different from us? Surely they must have been loving and hating even then? Been alone, arrogant or confused, felt anxiety or joy, just like us. For sure, I cannot understand them, they spoke a different language, had a different worldview. Other customs and beliefs than I attend to. Nevertheless, do that prevent me from identifying myself with them? To feel their human presence? I do not understand Liv, but love her no less because of that. In a similar vein art speaks to me despite vast distances in time and space.

Here in Prague I visited a comprehensive University collection that among others had been compiled by Bedřich Hrozný (1879 - 1952) an unusually impressive person. Besides his Czech mother tongue, Hrozný mastered several other languages - he spoke fluent English, Russian and German, as well as Hebrew and Arabic, in addition he knew a variety of more or less dead languages, like Latin, Sanskrit, Akkadian, and its closely related relative Aramaic, as well as Amharic (though that is a living language) and Sumerian.

Hrozný was also an able archaeologist and during excavations in Turkey he came across a vast hoard of clay tablets with Hittite characters, a dead language that he single-handedly managed to decipher.

This admirable man became after Czechoslovakia's split from the Austro-Hungarian Empire Rector of the venerable Charles University in Prague, founded in 1348. When soldiers of the German occupying forces in March 1939 came to the university in search of Jewish students, who had sought refuge within the main building, they were met by Bedřich Hrozný who in his flawless German, explained that this venerable university, like most similar institutions around the world, was autonomous and therefore off-limits to police and military. Bewildered the German soldiers turned back and the Jewish students could be brought to safety. Nevertheless, shortly afterwards all Czech universities were closed down and Hrozný had to maintain himself as private lecturer until he in 1944 suffered a paralyzing stroke and died eight years later.

Among my in-law's books I found an art book describing the Bedřich Hrozný collection and other university exhibits which can be found in Prague. The aesthetically pleasing photographs were taken by the renowned Werner Forman. The book was called Umenění čtyř světadílů, which apparently means "Art from four continents" and I decided immediately to visit the museum that now houses the university's art collection. It turned out that the collection, which is certainly not solely compiled by Hrozný, now is scattered in various palaces in Prague. The largest one, the Oriental collection, is found in the vicinity of the Charles University, housed in the Kinskýchpalatset at the Old Town Square. Incidentally Herrman Kafka had his haberdasher in the palace's ground floor and it also harboured the secondary school where his son Franz was taught for eight years.

A friend has told me that my blog entries are far too wordy and in this one I thus intend to devote myself more to images than words and thus make some visits to my personal “museum without walls”, where I to begin with find some works from the Hrozný collection - A Chinese tomb sculpture from the Fifth Century of BC. In its advanced abstraction it appears as a piece of modern art, both eerie and refined.

A terrifying demon of death, quite different from a soothingly smiling Buddha from 1300 AD, made by the Khmers in what is now Vietnam.

A so-called Ghandara Buddha from ancient Peshawar, which once with the Khyber Pass, the Gateway to India, as its centre covered large parts of current Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The Ghandara Culture, which flourished under the rule of the the Hindu Kush kings from 100 to 500's AD, was a mixture of Greek-Indian influences. Its refined art possesses a Greek dignity mingled with the realistic, yet spiritualized, Buddha representations we find further east.

A Buddha made in fourteenth century Siam presents through his features a closeness to his worshipers, though his appearance is spiritualized and he appears to be resting in himself.

A Buddha from the seventeenth-century Japan smiles quietly, though in a superhuman fashion. Even more than the Siamese Buddha, he appears to be present in a realm beyond our earthly existence, even though he also shows traits of those who worship him.

The Hrozný collection does not only display depictions of deities, but also several exquisite portraits of living beings, like a wooden sculpture from the fourteenth century representing an elderly Japanese man, with deep wrinkles at the corners of his eyes and a century later a younger Japanese is watching us, smiling though maybe with a certain tinge of distrust.

Besides the sculptures we find an exclusive collection of minor arts, such of lacquered boxes, Japanese netsukes and glazed Japanese and Chinese miniature sculptures from the 1800s. Here a geisha appears as if she was a three-dimensional representation of a contemporary woodcut.

The Karl University collections are not limited to "high cultures", but include several African, Pacific and American artefacts manufactured by indigenous people, these may cherished at the Náprstek Museum of Asian, African and American Cultures. Unfortunately its space does not allow displays of the permanent collection and the museum thus concentrates its efforts on temporary, though excellent, thematic expositions. By my visit I was impressed by small sculptures made by Siberian hunters, who virtuoso reproduce their prey; shamanistic totem animals like bears and caribou.

If the animals are stunningly naturalistic, depictions of people are more roughly done, nevertheless most of them are strange and intriguing, like a sculpture group depicting how a man carries his child on his shoulders.

Such human figures curiously enough remind me of the several thousand years old Syrian and Hittite sculptures which are included in Hroznýs collections. For example, a five thousand years old fragment of a Hittite woman's face, relic of a thousand years old tradition of women's representations present in everywhere in the Near East, like the enigmatic one metre high plaster sculptures depicting women dated to 6750 BC, which I four years ago saw at the Jordanian National Museum of Amman.

With wonder and anxiety I sometimes think about what might have happened to the evocative fragments of human creativity that impressed me during visits to areas which priceless treasures now are threatened by a temporary and utterly absurd fanaticism. I wonder, for example, what happened to the mighty deities I once saw standing on the backs of bulls and lions at the National Museum of Aleppo. Probably these ancient masterpieces are now turned into rubble by bombs and explosions. A tragedy which nevertheless pales by the thought of all senseless human death and suffering.

My visit to Palmyra forty years ago seems like a strange mirage. When I and my friends almost alone wandered amidst the ancient ruins we found it difficult to comprehend that such magical places existed in reality. It is perhaps not so surprising that if I now fear that there cannot be much left of the National Museum of Aleppo, particularly after having been confronted with pictures of the looted and utterly destroyed remnants of the museum of Palmyra. The beautiful female portraits we saw there are probably nothing more but a memory.

The world's oldest representation of a woman is not be found among the Middle Eastern fountainheads of human culture, but in a small museum in the village of Dolni Věstonice in southern Czech Republic, outside of which an Ice Age settlements was unearthed in 1923. Among many findings, there was a 4.5 cm women's head, which had been cut out from a mammoth tusk 28 000 years ago.

While I carried little Liv among the sculptures of the Hrozný collections, I recalled one of the most impressive art books I have read - André Malraux´s Les Voix du silence, "The voices of Silence" from 1951, in which Malraux writes how art has become even more boundless during our modern era, when photographs and films bring it into our homes and not only that - reproductive technologies make it possible for us to appreciate art in all its details, particulars we may have missed when are confronted with artworks in real life. In addition, we can easily compare different artworks and seek them out whenever we want to, through reproductions in the vast "museum without walls".

After calling attention to these phenomena Malraux presents a sumptuous buffet of art he appreciates most and does so in an imaginative and personal manner making me recall how my enthusiastic and eloquent art professor Aaron Borelius once opened one door after another leading to treasure chambers I had not frequented before.

Memories of the Faiyum portraits, Malraux´s book and my recent confrontation with the Hrozný collections aroused a desire to introduce some favourites of mine from my own museum without walls. The most beautiful portrait I ever seen I came across in an art book at Hässleholm´s library, many years ago, though it took a long time before I saw it in reality, not in the Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo where the Madonna belongs, but at an exhibition in Rome. She is a wonder of female beauty, radiating a mysterious energy. Antonello da Messina's Madonna raises one hand towards the angel, who is standing where the viewer is, telling her that she will be the mother of Jesus:

And the angel came in unto her, and said, Hail, thou that art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee: blessed art thou among women. And when she saw him, she was troubled at his saying, and cast in her mind what manner of salutation this should be. And the angel said unto her, Fear not, Mary: for you have found favour with God. And, behold, you shall conceive in your womb, and bring forth a son, and shall call his name Jesus. He shall be great, and shall be called the Son of the Highest: and the Lord God shall give unto him the throne of his father David: And he shall reign over the house of Jacob for ever; and of his kingdom there shall be no end.

Virgin Mary accepts the astounding message with calm. It is almost painful to be confronted with the perfection of such a masterpiece. What can I do other than look at it? Every attempt to explanation of its profound beauty becomes utterly useless, though its meaning is obvious – a representation of a young, beautiful and very special woman, caught in a moment, which according to the beliefs of any strict Catholic faithful has changed all human existence forever. It is the most profound work of art I know, but Antonello was not alone in imparting his portraits with an unusual, perhaps even suprahuman, radiance.

Girolamo Francesco Maria Mazzola, called Parmagianino, had the same ability. Parmagianino, whom his contemporaries hailed as a "born-again Rafael" died in 1537, only thirty-seven years old. According to his biographer, Giorgio Vasari, he died in debt, on the run from unfinished tasks, prematurely aged, like a fanatical hermit obsessed with alchemy and strange speculations. A tragic development that can be traced in Parmagianino´s self-portraits.

Vasari is a fascinating and enthusiastic storyteller, who likes to spice his stories with illuminating and peculiar anecdotes. However, it cannot be denied that Parmagianino´s paintings are endowed with a peculiar charisma, an almost ghostly character. Like the portrait called Antea at the Museum of Capodimonte in Naples.

Or his softly curled and spiritualized pale Jesus, who in a childish gesture withdraws from John the Baptist´s kiss.

Children´s almost otherworldly character has also been captured by Goya in his portrait of a boy in a red suit. Aron Borelius scared me ing pointed out that the boy seems to be a spirit, making him recall photographs of dead children that in the early twentieth century were common in his rural childhood district of Dalecarlia.

Such child portraits are completely different from Thomas Lawrence's images of prosperous, happy and wealthy kids, depicted with a freshness that beckons the viewer to touch them. Like his Calmady Children from 1823.

The rococo-like brilliance of Lawrence´s children is in stark contrast to the sublime portraits which became fashionable during Romanticism, contemporary to Lawrence´s artworks, where the artist's tempestuous brushwork often can be detected, a style that the versatile Lawrence, by the way, was no stranger to.

Much Romantic art and thinking was a reaction against the Enlightenment´s belief in reason. An intense interest in wild imaginations and not the least insanity developed, separated as they were from everything reasonable. The designation of a psychiatrist was at the time alienist, someone who investigates what is strange and different.

Alienists were interested in physiognomy, which meant that they judging from patients´ physical appearance, movement patterns, posture and especially their head shape and facial expressions assumed they could be able to determine the nature of their afflictions and find a cure. Unfortunately, the limited treatments at the time were mainly limited to various forms of body disciplining and shock therapy, almost all completely useless and even harmful.

In their quest for, as accurately as possible, depicting and systematizing their patients' bodily peculiarities several alienists turned to artists. Below are Ambroise Tardieu´s depictions from 1838 of a patient with dementia and another suffering from mania.

Tardieu was both engraver and alienist. His image of a wide-eyed woman, sitting on her bed in front of an open window, reminds me of a nasty episode that occurred when I for a summer worked in a mental hospital. One of the wardens suggested:

- Come, and I´ll show something funny.

We went into a room where a single patient quietly sat on her neatly made bed.

- How are we feeling today, Veronica [fictitious name]? wondered the warden.

- Just fine, answered Veronica, who according to the medical record suffered from a "schizoaffective disorder characterized by delusions, hallucinations and violent mood swings of a manic or depressive nature."

- Nice to hear that you´re feeling fine, Veronica. But, now I will let them in!

The warden opened the window wide. Astrid Veronica screamed, jumped up on her feet and in mindless panic pressed herself against the wall:

- Close it! Close it! she yelled at top of her voice.

Unperturbed the warden closed the window and Veronica fell back on her bed.

I shook violently inside. The warden´s ruthless behaviour was one of the most disturbing acts I had ever witnessed. Nevertheless, I did not report the incident, I was too young and inexperienced. All I did was trying to avoid him. His wicked grin when I ran into him made me believe that his manifest sadism had been directed against both Veronica and me.

Artists who themselves had suffered from mental disturbances have also been fascinated by physiognomy. Most famous is probably the case of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt (1736 - 1783), an Austrian sculptor who during his lifetime became famous for his so-called "character heads", i.e, 64 grimacing self-portraits made from a variety of materials, such as bronze, marble, resin and a special alloy of lead and tin that Messerschmidt had invented. Like many artists, he was fascinated by chemistry, or rather alchemy. Messerschmidt was obsessed by the idea of "universal harmony" and in his work he tried to apply the golden ratio. When he was 38 years old he applied for a post as a professor at the Vienna Academy of Arts. However, he selection board praised his skills, but discouraged his application arguing that Messerschmidt suffered from what they characterized as a "confusion in the head."

.jpg)

The rejection tossed Messerschmidt into a deep emotional crisis, aggravated by a chronic inflammation of the intestinal tract, which caused excruciating abdominal pain. To counter the painful attacks Messerschmidt obtain a habit of "pinching" his lower ribs in an agonizing manner. The pain triggered grimaces which he studied with great interest and then reproduced in the form of self-portraits. His madness made Messerschmidt imagine that he through his ”unnatural grimaces” angered the "The Spirit of Proportions", who reacted by inducing even worse torments upon the hapless Messerschmidt. The afflicted artist assumed he had no other remedy to fight the miseries caused by this hostile spirit than to create even more expressive character heads.

It is remarkable that Messerschmidt in his madness became an even more skilled sculptor than before. A similar case is Richard Dadd (1817 - 1882), an artist who when he at the age of 25 was travelling along the Nile suffered a severe sunstroke and became confused and violent, raving that he had become possessed by Osiris. After his return to England, Dadd began to suspect that his father was the Devil in disguise, killed him with a knife and fled to France, where he eventually was arrested after he in a coach had attacked a fellow passenger with a razor. He claimed to be controlled by demons and that the man he had killed in England was not his real father. Dadd spent twenty years at Bethlehem Hospital (Bedlam) in London. When Dadd´s alienist, Sir Alexander Morison, after ten years, retired and retreated to Scotland Dadd painted his portrait in front of his Scottish house, with hat in hand as if he was taking leave from his patient.

There are borderline cases - artists who portrayed mental patients while they themselves, as well as people who knew them, occasionally considered them as mentally unstable, crossing the borderline between what was considered to be normal behaviour and madness. A few years ago I came across a strange portrait by Oskar Kokoschka (1886 - 1980), it had ended up at the Musee Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique in Brussels and depicted the actor Ernst Reinhold after he had induced himself in a state of trance. Accordingly Kokoschka called his painting Der Trancespieler, "The Trance Actor".

Reinhold was a childhood friend of Kokoschka and had the same year as his portrait was painted been starring in Kokoschka´s scandalous piece - Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen, “”Murderer, the Hope of Women. A strange one act play about a Man with his horde of Warriors and a Woman with a gang of Maidens. In accordance with the Viennese zeitgeist the love between Man and Woman develops into a violent sexual struggle against the backdrop of the two groups of Warriors and Maidens either fighting each other or joining forces against the Man and the Woman. The whole act evolves more around form, colour and movement than being based on dialogue. This peculiar drama has been called the first expressionist play. Several viewers found the play to be both disturbing and incomprehensible, but the influential architect Adolf Loos and his friend the writer and journalist Karl Kraus were impressed.

Adolf Loos became even more enthusiastic when he saw Kokoschka´s paintings and listened to the artist explaining how he proceeded to accomplish what he strived for. Like his source of inspiration, van Gogh, he applied thick layers of oil paint and sometimes scraped the canvas, or used his fingers to smear the paint over its surface.

Kokoschka explained that he was trying to look into the soul of the people he portrayed. In his portraits, he wanted to give shape to "anxiety, corruption, disease, innocence, and even insanity." Kokoschka called his portraits of psychograms.

My sitters have to be induced into a state of mind in which they forget that they are portrayed, to do this requests a long experience of socializing with people, in particular personalities trapped in conventions and whose character thus has to be brought to light, somewhat like using a can opener [...] I try to keep the persons I portray in constant motion, entertaining them through discussions to distract them from the fact that they are being portrayed [...] I wanted to create an image that made it possible to preserve a human being not only as a portrait, but as a recollection.

Adolf Loos convinced Kokoschka to exhibit his first painting. He was already known as a graphic artist, Der Trancespieler was actually his first portrait of a man. The interest in Kokoschka´s oilpaintings was so great that Loos managed to persuade his friend Paul Cassirer, Berlin's most famous gallerist, to already the following year exhibit thirty works by Kokoschka. "Do not worry," he stated, "I guarantee it will be a sensational success." At the same time, Adolf Loos convinced another acquaintance, the manager of Vienna's newly opened mental hospital Niederösterreichischen Landes Heil- und Pflegeanstalt für Nerven- und Geisteskranke Am Steinhof “The Austrian Provincial Department for the Care and Cure of Mental Illness and Nervous Disorders at Steinhof,” to provide Kokoschka with the opportunity to portray some of its inmates. During two years, Kokoschka made fifty portraits of mental patients, as well as some famous personalities.

However, most impressive is, in my opinion, are Theodore Gericault´s (1791 - 1824) renditions of mentally ill patients, in which he, like Kokoschka, allows them to retain their individuality.

During his short life Géricault was attracted to the violent, macabre and strange, without denying his personal affinity with the wind-driven existences often caught in extreme situations. Through his art we may face the anguish of criminals condemned to death, or feelings of alienation of coloured people who had arrived in France's capital from its different possessions.

Such exotic strangers was by some artists bestowed with a timeless beauty, like Marie Guillemine Benoist´s portrait of a black woman from the Caribbean, painted in 1800, two years before Napoleon reinstated slavery in the French possessions (the slaves had been emancipated in 1794). Benoist´s sitter was a slave who Benoist´s brother-in-law had brought with him to France from Guadeloupe.

.jpg)

Slavery had been banned in France since the Middle Ages and slaves, or former slaves, who by their owners had been transferred to France was immediately granted their freedom and the right to be hired as servants. i.e. being remunerated for their services, as well as free to resign from their profession, rights that were maintained even after the restoration of slavery in the French colonies. Portraits of black servants is a niche in Western art history, a late example is the Swiss Felix Vallotton's depiction of a black housekeeper from 1911.

Vallotton´s even application of basic colours made me remember an exhibition I a few years ago saw in Stockholm - glossy collages made by a Dutch photographer named Ruud van Empel. Most pictures were of black children in a kind of Rousseauan jungle landscape. With “Rosseau” I mean when the naïvist master painter Henri Rousseau, a comparison that is not entirely irrelevant. Rosseau had never visited a jungle and van Empel, who comes from the small town of Breda, has not been in neither Africa nor the Caribbean. I found some of his pictures to be excruciatingly kitschy, but I nevertheless became fascinated by his depictions of girls dressed up in their Sunday finery. Such girls I have seen in countries in Africa and the Caribbean and van Empel´s beautiful image of a girl in green carrying a white handbag is undeniably archetypal. To me it is an unequivocally rendering of a girl being proud in her best clothes.

Benoist´s black woman is a timeless beauty and makes me wonder whether the concept of beauty is not both global and eternal. Take for example the famous Nefertiti head in Berlin's Neues Museum, which apparently was not intended to be a finished work of art, but rather served as a model in a sculptor's workshop for other artworks, which were carved in stone or perhaps even made from various precious metals, like the splendid mummy mask of Nefertiti's stepson, Tutankhamen.

.jpg)

I recalled Tutankhamen´s mask when I visited one of my nieces who lives in Brussels, more precisely in the leafy suburb of Tervuren, where Leopold II ordered the construction of the mighty Musee Royal de l'Afrique centrale for a World Expo in 1897. The big spctacle was intended to be a showpiece for the Belgian monarch´s great philanthropic project, the so called Congo Free State, which according to the infinitely greedy Leopold would bring civilization and prosperity to the interior of Africa, while it at the same time would prove to be extremely profitable for Europe.

Leopold II managed to sell his project to the renowned participants in a conference to which he in 1876 summoned explorers, philanthropists, missionaries and geographical associations from across Europe. His initiative was crowned with success when the Berlin Conference in 1885, convened to settle the imperialist spheres of interest in Africa, gave the Leopold-controlled International African Association a free hand to exploit Congo's natural resources, while at the same time guaranteeing the well-being and prosperity of the local people. The philanthropic cloak that Leopold used to cover his greed soon proved to conceal a ruthless exploitation of people. In order to earn vast amounts of money mainly from rubber and ivory, an estimated ten million men, women and children were killed during a period of fifteen years.

Some of the results of this unspeakably cruel episode in human history is the exquisite collection of Central African art in the Musée Royal de l'Afrique centrale. Since the museum is at walking distance from my niece's house I have visited it several times and during every visit I have been equally impressed by the expressive Congolese art, in particular sculptures and masks created by the Chokwes, whose twelve clans during the 16- and 1700s paid tribute to the King of Lund, who controlled a large area that now is divided between the The Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola and Zambia. Especially the masks with closed eyes and finely chiselled features exude a sublime and magnificent spirituality.

A similar chilly intensity can be found in much of the Central American art which developed before the Europeans arrived. An impressive example is the intense facial expression of the fertility goddess Tlazoteotl while giving birth.

Like in ancient Egypt, Central American people like Aztecs and Mayas appear to have had a formal, rigorous and highly aesthetic monumental art, parallel with an intimate, realistic portrait making.

Also in ancient Rome a realistic, everyday portraiture flourished alongside grandiose celebrations of influential political leaders.

A polarization that makes me think of Velázquez's masterpiece Bacchus Triumph from 1628. It appears as if this painting could in two halves, where the left side is dominated by the deity´s pale hull and an ancient veneration of vine, while the right half is dominated by rustic drunkards from Velázquez´s own times whom he, like the contemporary Spanish piqaresque authors, could study first hand and become acquainted with in any village tavern.

Rarely has proletarian drunkards been portrayed with such an empathy as Diego Velázquez was capable of, without turning them into picturesque staffage.

Velázquez´s earthy realism emerges both in his representations of dwarfs and cripples by the Spanish royal court, as in his fictional portraits of ancient greats, like his aging and worn Aesop.

One person who reached a respectable and vital age was Velázquez´s contemporary the abbess Jerónima de la Asuncion, at least if you consider that he portrayed this stern lady when she was 66 years old and was preparing herself to embark on one of the era's fragile vessels to covert stalwart pagans in the Far East. Ten years later, she died in the Philippines. A seemingly hard and pungent lady with hard grip on her crucifix, almost as if she would like to hit the idolaters with it.

Few artists have as El Greco, Domenikos Theotokopoulos a native of Crete, so deftly been able to capture the overwrought religiosity of many noble Spanish warriors, who after century-long battles with the Muslims nurtured a merciless hatred against all perceived enemies of the true faith. El Greco's dark hidalgos may be set alongside Francisco de Zurbarán´s pious monks as examples of the intense mysticism we find in Spanish saints like John of the Cross, Teresa of Àvila and Ignatius of Loyola.

Emotional intensity js reflected a few centuries later in the Romantic expressive portraiture, so different from the Enlightenment´s crystal clear depictions of self-confidently smiling philosophers, scientists, authors and aristocrats,

or ruthless Renaissance condottieri and grave Germans.

.jpg)

The great realist Albrecht Dürer did not shrink from depicting the ravages of time on a face, like in a drawing of his worn-out mother, like me 63 years old, four years younger than Velázquez´s tough Jerónima whose religiosity seemed to be of the same strict calibre as the Christ Pantocrator, "The Almighty," depicted in a mosaic from the 1000's in the abbey of Greek Daphnis.

Quite unlike Rembrandt's proletarian Jesus in seventeenth-century Holland, which also housed the masterful portrait painter Frans Hals, whose every brush stroke vibrates with dynamism and who, like Velazquez, did not hesitate to describe both the high and the low using the same undifferentiating eye.

I mentioned the Enlightenment´s crystal clear images of various celebrities, but even during that time there were artists who with sweeping brush strokes captured vanishing moments, energy and vigour in their portraits, like the virile Fragonard in France, or the sarcastic but robust Hogarth in contemporary England. The latter succeeded in Hals spirit to catch a shrimp vendor´s open smile. An joyful image that may gladden the heart of any visitor to London's National Gallery how may come across her on one of those gloomy, rainy days, which so often slouch heavy on the massive town.

A contemporary English artist like David Hockney often makes me think of the Rococo masters, his art is light hearted and skilful. In his loving portrait of his mother, a deeply religious and principled vegetarian, he makes use of a fluent brushwork reminiscent of Fragonard's virtuosity, though Hockney succeeds in achieving a greater psychological depth than the French master.

The intense gaze that Hockney's mother directs towards us makes me think of Titian's portraits in which we may encounter similar intense gazes. Or, even in Chuck Close´s huge canvases, which are all close-ups of faces, his own and others, often depicted in a variety of techniques. Close´s fascination with faces obtains a tragic connation if considering the fact that a spinal artery collapse that befall him at forty-eight years of age made his lower body paralyzed. Nevertheless, after this disastrous injury Chuck Close continues to concentrate all his impressive skills to painting huge close-ups of faces, while never rendering other parts of the human body.

The respect of their elderly mothers of such masters as Rembrandt and Dürer is reflected is reflected in the countless portraits of mother and child that have been an integrated part of Western religious art for centuries. It was not until the 18th century that mother and child pictures lost their almost exclusive connection with religion, mainly due to a vogue for "returning to nature" advocated by Rousseau. Suddenly it became opportune for high society ladies to take care of their infants and be depicted as caring mothers, like Louise Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun's tender portraits of herself with her son or daughter.

.jpg)

I have now during some evening hours been wandering around in my mental "museum without walls" and without structure or inhibitions followed one association after another. I now leave this realm at the same place where I stepped into it – how Liv looks into the eyes of her grandfather.

It makes me think of how I have aged, how long time that has passed since I myself was a small child, or since I carried around my own baby girls. I am now an old man, although I am not yet so painfully disfigured as the man in Ghirlandaio´s painting from 1490, where an old man with a horribly disfigured nose tenderly looks down at his grandson. I can easily identify with this man and recognize the boy´s look at his Grandpa and the gentle gesture with which he touches his fur edged mantle. They seem to say: "What do I care about Grandpa´s age and his dreadful nose - he is my friend and I trust him."

I do not have the same social status, background or attitude towards life as the old man in the picture. As my archaeology friend noted - we are infinitely far apart in time and space. But nevertheless, I am inclined to believe that the old man's love for his little grandson cannot differ much from my love for little Liv.

Fifty-five years before Ghirlandaio made his portrait of the old man and his grandson, Leon Battista Alberti wrote in his treatise on painting:

Painting contains a divine force which not only makes absent men present, as friendship is said to do, but moreover makes the dead seem almost alive. Even after many centuries they are recognized with great pleasure and with great admiration for the painter. […] Thus the face of a man who is already dead certainly lives a long life though painting. Some think that painting shaped the gods who were adored by the nations. It certainly was their greatest gift to mortals, for painting is most useful to that piety which joins us to the gods and keeps our soul full of religion.

What do I care about an artist´s thoughts and feelings, whether s/he is close to me in space and time, or not? Most important for me is the feeling and message an image conveys to me. Whether I will forget it, or include it in my “museum without walls”. I wonder what my life would be like without art, literature, music and film? Unbearably empty and dull.

Alberti, Leon Battista (1966) On Painting. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Hochschild, Adam (1998). King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Kokoschka, Oskar (2007) Mein Leben. Wien: Metroverlag. Malraux, André (1974). The Voices of Silence. London: Paladin. Lubor, Hájek (ed.) (1957) Umenění čtyř světadílů. Praha: Orbis. Reuter, Astrid (2002) Marie-Guilhelmine Benoist, Gestaltungsräume einer Künstlerin um 1800. Berlin: Lukas Verlag. Scull, Andrew (2015) Madness in Civilization: A Cultural History of Insanity from the Bible to Freud, from the Madhouse to Modern Medicine. London: Thames & Hudson. Scherf, Guilhem (ed.) Franz Xaver Messerschmidt 1736-1783. Paris: Editions Louvre. Tromans, Nicholas (2011) Richard Dadd: The Artist and the Asylum. London: Tate Publishing. Vasari, Giorgio (1988). Lives of the Artists: Volume 2. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics. Walker, Susan and Morris Bierbier (1997) Fayum: Misteriosi volti dall´Égitto. Milan: Electa.