MEGALOMANIA: Moths and power binge

They are there, resting among the brain circuits, ready to show up when you need them and sometimes even quite unexpected ̶ lingering memories (several have been cleared away and disappeared for ever), sayings and songs. Especially the latter have a tendency to move around behind the skull, serving as accompaniment to my thoughts. Today, I woke up to John Lennon:

You can go to church and sign a hymn.

You can judge me by the colour of my skin.

You can live a lie until you die.

One thing you can´t hide

is when you´re crippled inside.

An all-encompassing truth applicable to us all. I assume each and every one of us needs confirmation and thus hide our shortcomings. Though ̶ What's really wrong with us? The correct functioning of liver, heart, spleen or kidneys? Ancient people thought it was one or another of these organs that made us happy or sad, wild or mild. Of course, nowadays we assume the brain must have something to with it as well.

Recently, we visited our oldest daughter in Prague. During a moment of calm I browsed through one of her books with close-ups of moths and their wings. While looking at them I was affected by nostalgia. Several years ago, my oldest sister gave me a book about butterflies, which I never got tired of looking in, now the fascination returned. What magnificent beauty and diversity! Such enigmatic creatures. Several of them live only for a couple of days. Their splendour and senses are exclusively created for these few days. Some of them even lack digestive organs.

However, my Swedish butterfly book was far from Joseph Scheers Night Visions, which I found in Janna's bookshelf. The book was a work of art, which on big spreads presented the magnificence of night moths, which Scheer had caught during nights in the depths of an American forest, far from pesticide poisoned fields and night-illuminated cities. There were pictures of Hypropeia Frucoa, of an unimpressive stature ̶ though with a glowing colour arrangement, as if it had flown directly out of a red-hot furnace.

Or a close-up of Plusia Putnami, red and orange like the Hypopreia. Nevertheless, completely different.

On one page, two Great Peacock Moths flaunted their beauty. They are among the world's largest butterflies, similar but distinct from their European peers, which since the beginning of the last century have been studied in detail .

The author and naturalist Jean Henri Fabre, who Darwin called the Homer of Insects, wrote that "The only goal in life of a male Peacock Moth is reproduction and for this he is equipped in an outstanding manner." Even more fascinating than his magnificent wings is the male moth´s ability to find a female. Just after he has broken through his cocoon and dried his wings he to flies away in pursuit of a female, who may be miles away from him. In order to mate, the male flutters unobtrusively through forests and bushes and dies shortly after he has satisfied his urges

Fabre, who lived 1823 to 1915, described how he one day at the foot of a mulberry tree found the cocoon of a Peacock Moth. He brought it home and placed it in one of the steel cages he used to study insects' lives and development:

On the morning of the 6th of May, a female emerges from her cocoon in my presence, on the table of my insect-laboratory. I forthwith cloister her, still damp with the humours of the hatching, under a wire-gauze bell-jar. For the rest, I cherish no particular plans. I incarcerate her from mere habit, the habit of the observer always on the look-out for what may happen.

.jpg)

The Great Peacock Moth is a night butterfly. Moths, phalaina, differ from butterflies, rhopalocera, by being shaggy and with more compact bodies. They fly at night and sleep in the day. Some Peacock Moths have a wing span of almost 30 centimetres. Fabre explained what happened to his female moth:

It was a memorable evening. I shall call it the Great Peacock evening. […] At nine o'clock in the evening, just as the household is going to bed, there is a great stir in the room next to mine. Little Paul, half-undressed, is rushing about, jumping and stamping, knocking the chairs over like a mad thing. I hear him call me: “Come quick!” he screams. “Come and see these Moths, big as birds! The room is full of them!” I hurry in. There is enough to justify the child's enthusiastic and hyperbolical exclamations, an invasion as yet unprecedented in our house, a raid of giant Moths. […] We enter the room, candle in hand. What we see is unforgettable. With a soft flick-flack the great Moths fly around the bell-jar, alight, set off again, come back, fly up to the ceiling and down. They rush at the candle, putting it out with a stroke of their wings; they descend on our shoulders, clinging to our clothes, grazing our faces. The scene suggests a wizard's cave, with its whirl of Bats. Little Paul holds my hand tighter than usual, to keep up his courage.

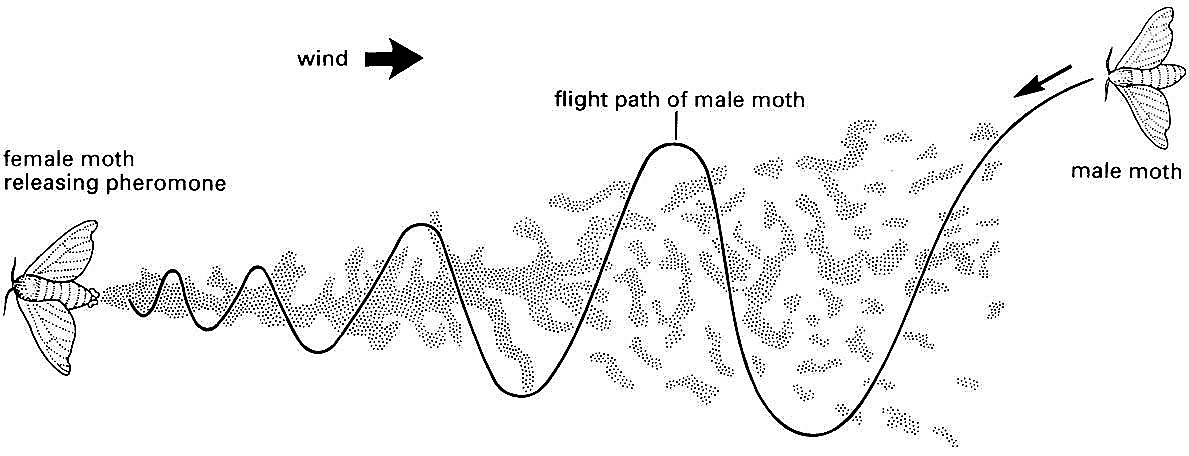

Somehow, the female had attracted males who were hundreds, maybe thousands of metres away from her. But how? Of the three senses a Peacock Moth possesses, Fabre assumed that sight and hearing were irrelevant to the males´ search for the female, the sense of smell remained. If Fabre hermetically insulated the female moth’s cage with glass, cotton and other materials, the male Peacock Moths did not show up. Likewise, when Fabre cut off the antennas of the male suitors, they became unable to find and reach the female.

When Fabre filled the room where he had placed the butterfly cage with strong fragrant substances, such as naphthalene and others, this did not at all prevent the gallants from appearing and desperately crawl over the cage's network. Perhaps the sense of smell could be ruled out as a means of navigation? Possibly could the electromagnetic waves recently discovered by Heinrich Herz explain the moths´ amazing ability to find each other?

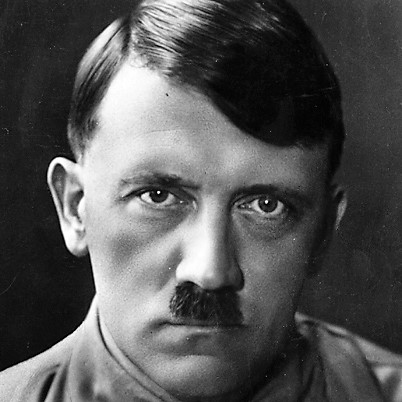

The solution to the problem did not come until 1957, emanating from one of the eighty German Max Planck Research Institutes, which all have had an outstanding significance for human thinking. In 1936, Professor Adolf Butenandt became a member of the National Socialist Party, and shortly afterwards he was appointed as Director of the Biochemistry Department at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute (after WWII these research institutes were renamed Max Planck Institutes), in 1939 he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

A membership in the Nazi Party was probably a prerequisite for Butenand's appointment, though the Party's disgusting ideology apparently did not contradict the profoundly conservative views of the professor, among other things demonstrated by the deep Schmiss, Gash, which adorned his left cheek, a sign of his membership in a conservative student association, where fencing scars were a sign of valour and honour. Butenandt's relatively late membership in the Nazi party was maybe due to the fact that it´s ideology was not sufficiently conservative to his taste.

Adolf Butenandt has been honoured as one of German scientific giants. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for isolating a variety of sex hormones, including estrone, testosterone and progesterone and he was crucial for the mass production of cortisone. However, unpleasant things lay buried in his past, including his cooperation with his friend and colleague Ottmar von Verschuer, Joseph Mengele´s superior, whose Institute of Human Heritage and Eugenics was housed in the same building as Butenand's biochemical institution.

Verschuer, who rightly pointed out that “the German people's Führer is the first statesman who has elevated genetic biology and racial hygiene to become the guiding principle of a country's regime” had several employees who performed dreadful medical and genetic experiments in Auschwitz. After WWII, Verschuer was sentenced to fines, though allowed to unabated continue with his “scientific” activities, though without the same cruel experiments on human beings that earlier had been an essential part of them. In 1969 died in a car accident, never demonstrating any signs of remorse for his merciless cruelty.

Butenandt, as one of the leaders in the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes, must have been well aware and also benefited from the grotesque, painful and lethal medical experiments performed witin the concentration camps. Among other things, it has been proved that one of the researchers who worked directly under Adolf Butenandt, Günther Hillmann, regularly received blood samples and other human organic material collected by Josef Mengele in Auschwitz. Such organic material were apparently also sold and exported to other institutions. In his memoirs, the Swedish academician Lars Gyllensten mentions how he, in the 1940s, as a medical student at the reputed Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, worked with preparations from humans, these were often in poor condition. However:

Fresher preparations from recently executed humans came through the mediation of a German anatomy professor. With abhorrence I still remember a typical Jewish nose embedded in paraffin.

After the war, Butenandt claimed that he had supported and committed himself to "pure science, impartial and independent of politics", a statement that actually did not contradict that waht he had been guilty of supporting unethical and inhumane "science". In Nazi Germany, like in many other places where scientific thinking is worshiped as one of humanity´s most admirable qualities, basic research has often been carried out with an astonishing lack of empathy.

After the end of WVII, Butenandt continued his acclaimed and ground breaking research until his death in 1995. When he retired in 1972, Butenandt had for some tears been president of all Max Planck Institutes. His activities during the dark war years and Butenand's involvement in grotesque medical barbarity has been difficult to track since immediately before his relocation to the University of Tübingen in 1944, Butenandt ordered the destruction of all files labelled Geheime Reichsache, Secret National Affairs, which could be found within the Biochemical Institute's archives.

It was Butenandt´s research that was the main reason for the solution of the mystery of butterflies´ navigational skills. His research team at the Biochemistry Department at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, under the direction of Peter Karlson, who despite his Swedish-sounding name was born and raised in Berlin, dissected no less than 500,000 newly hatched Domestic Silkmoths (Bombyx Mori) and could finally from their scent-producing glands extract a triacylglycerol ester that Butenandt named Bombykol.

The reason for renaming the reorganized the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes to Max Planck Institutes was to pay tribute to the unblemished nuclear physicist who had been a well-known anti-nazi. The biochemical division of the institutes moved to Munich where Peter Karlson continued his experiments with bombykol, now in collaboration with the Swiss entomologist Martin Lüscher. They managed to identify a molecule that through the air could be transferred between individuals of the same species and then recieved by specific neurocircuits. The molecules, which are few in numbers, spread together with clouds of other molecules. Scent molecules are inconspicuous and well below what humans and other animals can consciously perceive. This was certainly the reason to why Fabre's spreading of strong smells around his Peacock Moth´s cage did not seem to interfere with the mating urge of the males.

When Karlson and Lüscher managed to isolate scent molecules from silk moths, they found that they could attract the attention of male moths even without the presence of a female moth. They repeated their experiments with other butterflies and found that the same phenomenon was could reproduced. In 1959, they named their discovered substances pheromones.

Soon researchers discovered that pheronomes can give rise to different kinds of behaviour, not just those directly linked to reproduction and that pheronomes have been developed in a specific manner among different animal species. Pheromones are manufactured in animal bodies and spread to their environment to affect other individuals. "Simple" animals like fish and insects release pheromones, for example to alert their fellow beings about various dangers, so-called alarm substances.

Particularly interesting is the role of pheromones for eusocial animals, living in organized, hierarchically designed societies where thousands of individuals interact and sacrifice themselves for the general good. Some hymenoptera, such as bees, wasps and ants, live in communities that appear to act as a single creature (or even “brain”), where individual creatures are completely subordinate to specific functions. The cooperation of these animals and their individual efforts appear to be largely controlled by the excretion of chemical substances (the pheronomes), but sound and touch may also play a role.

Ants leave pheronome trails on the ground, thus creating pathways for their activities. If food runs out in a particular place, or if insurmountable obstacles arise, specific scout ants create new pheronome trails to other food stuff places, while the old trails evaporate. At the same time, the scouts are also capable of leaving false, confusing tracks for other, food-competing insects, or alien ant colonies.

A damaged ant releases alarm pheronomes causing its peers to either attack an enemy, or escape. Ants blend pheronomes into their food to achieve specific results and individuals also exchange chemical signals between them.

Soon, pheromones were also found in mammals and suspicions arose that even human behaviour could, to some extent, be stimulated and controlled by fragrance signals, unique to our species. Certainly could the reception of scent impulses of humans not be as powerful as it is in dogs, which in their olfactory system have more than 200 million fragrance receptors, compared to the six to twelve million within the human nose. Scent receptors are cilia covered nerve cells enclosed in noses and snotes. The cilia perceive the pheromones and their attached nerve cells transmit the information to the brain for processing. Pheromones make an individual being´s organic system aware of the emotional state of other organisms ̶ whether they are threatening, friendly or want to mate.

However, the general scientific opinion seems to be that pheromones do not have a significant impact on humans´ emotional life, but that has not prevented scientists from considering humans as some kind of complicated machines acting on external stimuli, which in turn triggers processes within us, completely dependent on substances and various forms of combustion and other transforming processes.The discovery of pheromones thus raised great hopes among researchers active within the war industry. They argued that it would be great if we could find substances that reprogrammed the central nervous system and, for example, blocked feelings of fear and faintheartedness to make us ruthless and brave.

When Albert Hofmann in 1936 managed to synthesize LSD, he found through his own experiences and animal experiments that the drug had a strange impact on the central nervous system. For example, LSD got cats to stare absentmindedly into empty space and if mice were released into their glass cages, the cats either left them unmolsted or became extremely scared of them. Chimpanzees broke against flock behaviour and scared fellow apes out of their wits. Spiders spun more precise webs than before, but when higher doses were administered their work became a mess.

In the 1950s and 60s, the US Army performed extensive drug experiments within its Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland, experimenting with various substances, not just LSD, but also BZ (3-Quinuclidinyl Benzilate), THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol), Ketamine and an assortment of different opiates. It was easy to discern that the drugs affected animals and people's behaviour, but the results were difficult to predict and controle. There were too many factors that disturbed the achievement of simple, predictable effects.

We humans are certainly an accumulation of nerves, organs and electrically charged particles. This was something that Adi Shankara preached already in 9th centruy India. His conclusion became something like that of the seventeenth-century philosopher Baruch Spinoza ̶ namely that spiritual and material worlds are intimately united and constitute an all-encompassing reality. For Adi Shankara, this reality was identical with the universal soul, the Ultimate Reality ̶ Brahman. All our search, all our pursuit, our world and existnece, are nothing else but an illusion, a Maya. Our identity with the entire creation is expressed through the formula Tat twam asi, तत् त्वम् असि, "That's You". We are an integral part of the whole, there is nothing to worry about.

There is no other world other than this;

There is no heaven and no hell;

The realm of Shiva and like regions,

are fabricated by stupid imposters.

Do you recognize it?

Imagine there's no heaven.

It's easy if you try.

No hell below us,

above us, only sky.

Imagine all the people living for today.

Imagine there are no countries.

It is not hard to do.

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion, too.

Imagine all the people living life in peace.

The ant expert Edward O. Wilson has a tendency to compare human societies with those created by eusocial insects. According to him, eusocial insects and humans are among the few animal species (exceptions among the vertebrates are mole rats) constituting complex societies based on a division of labour that benefits other members of large groups. Eusocial animals are engaged in a joint pursuit of food, as well as they practice agriculture and war.

According to Wilson, humans are far more dangerous for our planet than other animals, which are driven by instincts developed over 100 million years. Their specialization and survival are favoured by their smaller brains and limited emotional life, which made them well adapted to the's biosphere. We humans, on the other hand, have developed an astonishing brain capacity. We have created new, sophisticated means of communication and multi-faceted cultures that have released us from dependency on specific habitats. This development has place at an amazing and apparently devastating speed. The rest of the creation has neither had the time, nor the opportunity to adapt to the completely new environment that parasitizing human beings have created all around the planet and all existence is now breaking at its joints.

How did all this come about? Wilson refers to another scientist's opinion - Richard Dawkins's “selfish gene”, which makes us humans different from all other creatures. Other animals generally act in such a way that their actions favour a significantly larger group of individuals than those who are close to them. The "selfish gene", on the other hand, tells us humans that it is far better to worry about and take care of individuals who are in our absolute vicinity, than to engage ourselves with other members of the large groups of individuals who make up a society. We may be able to do everything in our power to help someone who is really close to us, instead of acting on behalf of a large society that does not recognize us as individuals. Wilson quotes Darwin, who wrote that if a limited group of people lived close to another and

included a great number of courageous, sympathetic and faithful members, who were always ready to warn each other of danger, to aid and defend each other, this tribe would succeed better and conquer the other.

Wilson assumes that we humans are a kind of eusocial apes. Like eusocial insects, the early hominids, our ancestors, had some group members collaborating in taking care of their joint offspring, while other group members were hunting or gathered food, a development that also characterized the emergence of ant communities. However, while the ants for millions of years developed their societies to form a single all-encompassing organism, a kind of common brain where chemical substances and electrical impulses connect a wide variety of activities, the “selfish gene” appears have enabled us humans to carry such a world within ourselves, within our own sophisticated, individual brains, while we at the same time, within a broader context, depend on and cooperate with other human beings. The result is a wide-ranging confusion, in which selfish genes fuelled by mainly chemical substances are creating egomaniacs, who nevertheless are linked to common interests, desires and actions of wider communities.

I do not think human empathy can only be linked to things like pheromones and nerve activities. Processes governing feelings of love and compassion must be far more complicated than that. Whatever Wilson and Dawkins might claim, I do not think science has all the cards on hand, of course, it is an extremely important tool in our constant quest for explanations and solutions, but I am still inclined to agree with Hamlet when he assures his friend that “there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

There is love and compassion, something that is not so hard to understand. We want to be liked and loved. If we express love and consideration to others, then we wish to receive such attention for ourselves as well. Not true? But, is it really so? Hardly. How often do I not get angry and annoyed myself? How often does humanity not violate itself? Are we all crippled inside? Is there something that is not quite OK within all of us? “The time is out of joint. O cursed spite. That ever I was born to set it right!" No, I do not really think that is my task. My efforts are far too insignificant. However, mere existence is a constant struggle.

After Prague we went to Berlin to visit our younger daughter. During the seventies I had been there several times; when I studied History of Art, or together with my comrades, as teacher for a school class and when I worked as a waiter on the ferry between Sweden and East Germany. Then West Berlin was hectic and confined, with demonstrating, highly politicised students and an intense nightlife with punks in Kreuzberg. East Berlin was grey and heavy underneath dirty clouds from coal furnaces, which still were used to warm the city. Remaining ruins from the War could be seen everywhere, but even there life was strange and exciting, with its Communism and Black Market, which meant we did not know what to do with all the money we got from illegal money exchange.

Now everything was different, clean and modern, the wall and barbed wire were gone. The east was beautiful, with large parks, piteously restored houses and churches, excellent bars and restaurants filled with young people and eccentrics, art and theatres everywhere. Berlin ist noch eine Reise wert.

The feeling that the war had not ended. The wall, which cut through the heart of the city like an infected wound, drunken American soldiers, the ruins, Cold War and Stasi ̶ all that had blown away in the summer heat. Hoever, death still lurked under the surface, old wounds had been reopened through sinister monuments.

Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas, Monument to Europe's Murdered Jews ̶ at a first glance I was surprised. Was it not any worse than that? A mass of concrete sarcophagi spread over a large area and were criss-crossed by narrow cobblestone corridors. It was only after we had stepped in between the cement cubes that a gloomy cold made itself present; the heavy presence of the dead, their suffering, the ruthlessness of their destruction. I assumed I was beginning to understand the idea behind the monument. The perfectly arranged lines of concrete blocks seemed to mirror the perfection of an ice cold system that had been carefully calibrated to achieve the most effective slaughter possible. The higher the concrete blocks rose around us, the more obvious it became that the walls were leaning in an irregular manner and that the cobblestone paths rose and sunk.

Passing in the sunshine between the lower cubes was maybe a way of portraying how Nazi victims had walked through sunlit streets, on their way to starvation in overcrowded ghettoes, or to freight cars which would bring them to mass executions, being suffocated to death in hermetically sealed vans, or end up in the inferno of extremination - and concentration camps. Indescribable suffering and humiliation shadowed by clouds, fattened by smoke from constantly corpse-fed furnaces and slaughter pits.

Soon we were surrounded by tall, blackened concrete blocks that obstructed our view, making us feeling uneasy and abandoned, an increasing sense of claustrophobia. Above us only blue sky over which a helicopter buzzed like a gigantic horsefly.

We continued our walk under the lush tree canopies that now embellish Tiergarten in front of Brandenburger Thor, liberated from obnoxious border guards, its dreadful wall and barriers of concrete and barbed wire. Enclosed by the trees was a circular pond of black water surrounded by irregular stones inscribed with guesome names ̶ Dachau, Stutthof, Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück, Plazow, Gross Rosen, Mauthausen, Auschwitz, Birkenau, Majdanek, Sobibor, Belzec, Chelmno and many more, several names were unknown to us, though we knew those were places of death and suffering. This was the memorial dedicated to Porajmos, The Devouring, the destruction of between 200,000 and 500,000 European Roma and Sinti.

In the middle of the dark water was a triangle, the badge of concentration camp prisoners (Roma and Sinti were forced to carry a black triangle, signifying “asocial element”) always adorned with a flower bouquet. Around the stagnant water of the pond ran a narrow stream of water, maybe suggesting that many Romas have been, and many still are, nomads constantly on the move, in contrast to the pools immovable, dark waters ̶ death and forgetfulness of the Nazi extermination camps. Above the running water was a Roma poem, written with rusty metal letters: "Gaunt face, dead eyes, cold lips, quiet, a broken heart, out of breath, without words, no tears.”

Again, helicopters buzzed above us. Benjamin Netanyahu was on a state visit to the Government in Berlin. It was hard to avoid thinking about the 58 Palestinians whom the Israeli army had killed fourteen days earlier. Will this madness never come to an end?

On our way away from the monument of Porajmos, we passed a parking lot, which I knew was on top of Hitler's bunker. Under us was the underground lair where Hitler had trudged around while 500,000 people died above him during the final battle for Berlin. A signboard described the Führerbunker.

One and a half month before his suicide on the thirtieth of April 1945, Hitler had with an "ice cold voice" told Albert Speer:

If the war is lost, the people will also be lost. There is no need to be concerned about the essentials the German people would need to survive at even a most primitive level. On the contrary, it is better to destroy these things, to destroy them ourselves. Because the [German] people have proved they are the weaker ones, and the future belongs to exclusively to the stronger people in the East. Besides, after this struggle, those who are left will only be the inferior ones, for the good have fallen.

Hitler had previously declared that he wanted come down in history "unlike any who had ever existed before" and surely he got it right ̶ Hitler's appalling contribution to history was that he was the ultimate cause of seventy million people's death.

Such a ruthless desire to be remembered at all costs, is that also created by the chemical processes governing our existence? Is there any creature, apart from man, which in its boundless quest to exegi monumentum aere perennius, to build monuments over itself that are more persistent than copper, are becoming so blinded by self-love that it disregards the pursuit for happiness and suffering of others, prepared to sacrifice thousands of millions of fellow beings on the altar of its own greatness?

The story is filled with powerful lunatics. For example, Saparmurat Atayevich Niyazov, self-appointed Father to the Turkmen ̶ Turkmenbashi. He renamed the days of the week and the months of the year after himself and members of his family.

Opposite his sumptuous presidential palace, he ordered the construction of a 120-metre-tall tower, crowned by a gold-plated sculpture of himself. The statue is mounted on a rotating disc, which makes the impression that the despot is continually glancing at the sun. Evil tongues in Turkmenistan's capital, Ashgabat, point out the monument´s likeness to a toilet-bowl plunger.

When a foreign journalist asked Turkmenbashi, who had forbidden the wearing of long hair, beard and golden teeth, if he did not think it was a somewhat embarrassing with all these gold-covered statues by himself, which disfigured towns and villages all over the country, the despot answered unabashed:

̶ I admit it, there are too many portraits, pictures and monuments [of me]. I don’t find any pleasure in it, but the people demand it because of their mentality.

Turkmenbashi decided that all libraries outside the capital would be closed. They were an unnecessary expense, since according to his opinion most rural residents were unable to read a book, apart from his own Ruhnama, The Book of the Soul. Ruhnama was, and probabaly still is, mandatory reading for all Turkmen college students, state employees and for those who aspire to obtain a driving license.

According to the few non-Turkmen who have managed to get through the wretched thing, the Ruhnama (the book has in Turkmenistan been translated into no less than forty-one different languages) is a megalomaniac drivel, a concoction of autobiography, Turkmen folklore, premeditated history, cooking and dietary advice, musings about the misgivings of Soviet times, boastful, exaggerated promises and Turkmenbashi's miserable poetry. However, this did not prevent the great leader from considering his work as being almost as powerful reading as the Quran and an excellent self-help guide for all Turkmen.

The author Paul Theroux wrote about a conversation he had had with a Turkmen taxi driver:

“He was on TV last night,” my driver said. “Well, he’s on almost every night.” Turkmen almost never said Turkmenbashi’s name aloud. “He said, ‘If you read my book three times, you will go to Heaven.’”

"How does he know this?”

“He said, ‘I asked Allah to arrange it.’”

Theroux read the concoction, but acknowledged that he was prepared to put his soul's salvation at stake because no one could make him read such a dull book twice.

Even in such a repressed country as Turkmenistan, not everyone could accept being fooled by an apparent madman and some exasperated underlings tried to kill him. The attempt failed and the consequence was a ruthless terror against real and imagined dissidents, many were imprisoned, tortured and executed.

Was Saparmurat Atayevich Niyazov a medieval, Eastern despot? Hardly, he was highly contemporaneous and died in December 2006, followed by the former dentist Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, now bearer of the honorary title Arkadag, Protector. Perhaps it is Berdymukhamedov's odonatological background that has made him love whiteness. Dark-coloured cars have since January 2018 been banned from the streets of Ashgabat. Such vehicles were seized by the police and their owners were forced to repaint them in white or silver at their own expense.

Like his predecessor, Berdymukhamedov likes gold as well, and in 2015 he “accepted” an equestrian monument. Moulded in bronze and covered with 24 karats gold, Berdymukhamedov is represented mounted on a horse on top of a 20 metres high, dazzlingly white, marble cliff. When he in 2014 was approached "by people who wanted to honour him" with an equestrian monument, the Protector modestly replied:

̶ My main goal is to serve the people and the motherland. And so, I will listen to the opinion of the people and do as they choose.

Why do narcissists have this taste for gold and marble? In his book Dictator Style, Peter York describes some outstanding features of dictatorship and home decoration:

1) Big it up: Make sure that everything is seriously over-scale. 2) Go repro: Dictators like the old style because it looks serious and involves a lot of gold and fancy work. 3) Think French: Repro French decoration and furniture has been the taste of thrusting New Money for 150 years. […] oval-backed gilt chairs [and] naked-lady paintings in pinky-green oils. 4) Think Hotel: Hotels – as shiny as possible – should be your inspiration. 5) Go for Gold starting with the taps. 6) Get more glass: Chandeliers are the diamonds of interior decoration. 7) Have important nineteenth century oils: French salon painters have found a second home in dictator land. 8) Involve brands: Choose names people know: Go Mercedes, go Ming, go Aubusson. 9) Make it marble: Go in for as much marble as possible. New marble, obviously, as the old stuff can be distinctly manky. 10) Have yourself everywhere: Celebrate your achievements. You´re doing it for the people.

What these inflated potentates seem to be striving at is to cover up their own inner defects, their total lack of empathy. That they are in fact crippled inside. An outlandish environment might make us forget their pathetic humanity. Are they human? Perhaps too human, equipped with a mutated selfish gene turning them into monsters. They cannot be susceptible to any pheromone forcing them to interact with other human beings and sacrifice themselves for the general good. A butterfly living for a day, only to satisfy another creature and then die in complete forgetfulness, must for these despots appear as the highest form of perversity.

Billington, Ray (1997) Understanding Eastern Philosophy. London/New York: Routledge. Blum, Deborah (2012) “The Scent of Your Thoughts” in Ariely, Dan and Tim Folger (eds.) The Best American Science and Nature Writing. Wilmington MA: Mariner Books. Fabre, Jean Henri (1998) Fabre´s Book of Insects. Mineola NY: Dover Publications. Fest, Joachim (2005) Inside Hitler´s Bunker: The Last Days of the Third Reich. London: Pan Books. Scheer, Joseph (2003) Night Visions: The Secret Design of Moths. New York/London: Prestel Publishing. Schieder, Wolfgang and Archim Trunk (eds.) (2001) Adolf Butenandt und die Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gesellschaft: Wissenschaft, Industrie und Politik in “Dritten Reich”. Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag. Theroux, Paul (2007) “The Golden Man: Saparmurat Niyazov´s reign of insanity” in The New Yorker, May 28. Tinbergen, Nico (1978) Animal Behavior. New York: Time-Life Books. Wilson, Edward O. (2013) The Social Conquest of Earth. New York: Liveright Publishing. York, Peter (2006) Dictator Style: Lifestyles of the World's Most Colorful Despots. San Francisco: Chronicle Books.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)