NORTH ITALIAN TRECENTO: Noble simplicity and quiet grandeur

The attention paid to COVID and the disgusting war in Ukraine might become stifling. Of course, you must be vigilant and show solidarity, certainly quite valuable human qualities – in contrast to selfishness and propensity for violence, which also, unfortunately, are an intricate part of human behaviour. Nevertheless, so are imagination and aesthetics, something that makes me occasionally take refuge in music and art. For a couple of days now, I have stepped into the aesthetic richness that left its mark on northern Italian art for a couple of decades at the end of the twelfth century and the beginning of the thirteenth century.

It happens that I occasionally wonder why I find so much pleasure in looking at art. Recently I found a possible answer in a book by the German philosopher Wolfram Eilenberger, Time of the Magicians, in which he writes about an equally strangely innovative period as the Italian late Middle Ages, namely the 1920s when European science, art, literature, music and philosophy underwent a period of amazing transformation.

As was the case with the Italian Gothic, the seeds had been planted during an earlier generation, though the blossoming occurred due to both a questioning and a fulfillment of previous discoveries and ambitions.

By Eilenberger I found interesting analyzes of the thinking of Heidegger, Cassirer, Wittgenstein and Benjamin. Some of Walter Benjamin’s theories could possibly be explanations for my great appreciation of art.

Benjamin believed that the contemplation of art and thus also art criticism were based on co-creation, a form of ”completion” of suggestions created by the artist. Like the artist, the viewer is affected by the instability and changes that prevail within her/his psyche, as well as the time period and surrounding environment in which both the creator and the obeserver find themselves. Art criticism is thus also criticism, or appreciation, of yourself. An artist and a spectator are on the same level , in the meaning that both are characterized by their experience of the outside world. A work of art’s "meaning/message" is not carved in stone, it finds itself in a state of constant change and thus becomes a symbol/image of our own existence, the inner and outer worlds that have been creating us and are continuing to do so.

'

Benjamin’s observations about art are to a large extent based on his philosophical predecessor Karl Wilhelm Friedrich von Schlegel (1772-1829) who argued that for a critic it is not enough to immerse aesthetically in a work of art, such an activity becomes ”complete” first when s/he is able to discern its different layers of technique, interpretations and presentation, only then can s/he scent its ”inner secret”.

Schlegel, however, was far from being a dry prig or stickler who recommended intellectual dissections of works of art. He was more of an arch-romantic who believed that:

Through artists mankind becomes an individual, in that they unite the past and the future in the present. They are the higher organ of the soul, where the life spirits of an entire external mankind meet and in which inner mankind first acts. […] Only a man who is at one with the world can be at one with himself.

Benjamin was also something of a romantic and considered that too much speculation and intellectual ”dismemberment” of a work of art ”destroys its external aspect - its beauty”.

Back to late medieval art. There is a remarkable calm hovering above these works of art, an exquisite melancholy, a compassionate closeness. Certainly there is also a presence of death and despair, maybe a premonition of the ravages of the plague that would soon kill an estimated 25 million of Europe's inhabitants, i.e. between 45 and 50 percent of its entire population.

Bloody wars were fought, though those were generally limited clashes between hired mercenaries and just a foretaste of what was yet to come – future religious wars when cities and fields were ravaged and no one was spared, neither professional soldiers, nor civilians.

The stallions of the apocalypse stood snorting in their stalls, while their riders – the Conqueror, the War, the Hunger and the Death – prepared themselves for their task of filling the world with misery at the command of a cruel lord who was going to pour the murderous content of his cauldrons of wrath on his own creation.

The Bible’s worst, over-interpreted and perhaps most influential book, favourite reading for vengeful and fanatic fruitcakes all over the world, was during these times remembered and generously quoted in art and scriptures – St. John’s Book of Revelation with its undeniably imaginative, but incredibly bloodthirsty vision of the Last Judgment, the punishment of sinners and the initiation of their eternal torment. An admittedly poetic, but nonetheless extremely nasty and vengeful book, a complete contradiction to Jesus’ message of love that I often have wished had never been written at all.

However, among Italy’s Gothic artists, the judgmental Jesus appears to be almost doubtful about his role as judge and destroyer. Maybe he even feels sorry for the victims of his divine wrath.

As he sits in judgment in Giotto’s Last Judgment, Christ seems to be thoughtful, yet calm and collected, far from as being so upset and condemning as Michelangelo’s judgmental Christ, created 240 years later.

However, the consequences of Christ’s judgement are the same. In a blasting firestorm sinners are hurled down into their never-ending torment in the depths of Gehenna.

They are dragged away by hard-working demons,

hangs like bunches of grapes from the cliffs of Hell.

A fat, grotesque Satan grabs them one by one and devours them as if they were appetizing tit-bits.

But even here, several of the damned seem to be strangely collected. Misers and victims of lust seem to patiently accept their destinies while they calmly and irresistibly allow themselves to be led down into the pits of Hell.

A distraught sinner tries to hide behind the trunk of the Cross, though it is doubtful whether he will escape his condemnation.

Here we find some of the desperate humor that often shows up in Gothic art. As in Taddeo Bartolo’s Inferno depictions in San Gimignano, with their fat sinners and heinous demons.

It is a world that Mikhail Bakhtin describes in his history of Rabelais and medieval laughter. A lush, popular culture that mocked the establishment and political correctness through a drastic wit that paid homage to the anarchic, liberated, and most forbidden, bringing forth the ”grotesque body” dominated by the satisfaction of primary needs such as sex, defecation, urination, eating and drinking. Through gluttony and unleashed urine-and-poop humor, life's victory over control and oppression is celebrated. The ”lower bodily stratum” is united with satire and grotesqueness and is thus transformed into a celebration of human existence, of becoming something indivisible, universal and beneficial. From these subversive conceptions art and poetry are created - the medieval Carmina Burana or Rabelais writings where high and low are mixed with grunting, heckling, unbridled, life-affirming and at the same time intellectual creativity.

A life attitude embodied in the Swedish poet Gunnar Ekelöf’s depiction of hell:

How Hell is com4table!

There Lusterans and Crapolics sit

and pray in latrine and grease

Gape in in excelsis Deo?

Pax in terrore!

Pooh, mine in the bush,

bonae voluptatis.

(translation by Per Bäckström)

In Italian art even demons may seem to show human emotions, other than cool enjoyment in the bullying and tormenting of the mortals. In Giotto’s depiction of Saint Francis expelling the devils from Arezzo, we discern one of them who seems to be saddened by being forced to leave his abode.

In Florence’s Santa Maria Novella we do in Andrea Buonaiuti’s fresco see how Jesus Christ descends into Hell to free Adam and Eve. The devils look on in amazement, unable to stop Christ´s unexpected action. With wit and knowledge of different reactions to unanticipated deeds, Buonaiuti depicted the demons’ wonder and amazement at this intrusion into their domain.

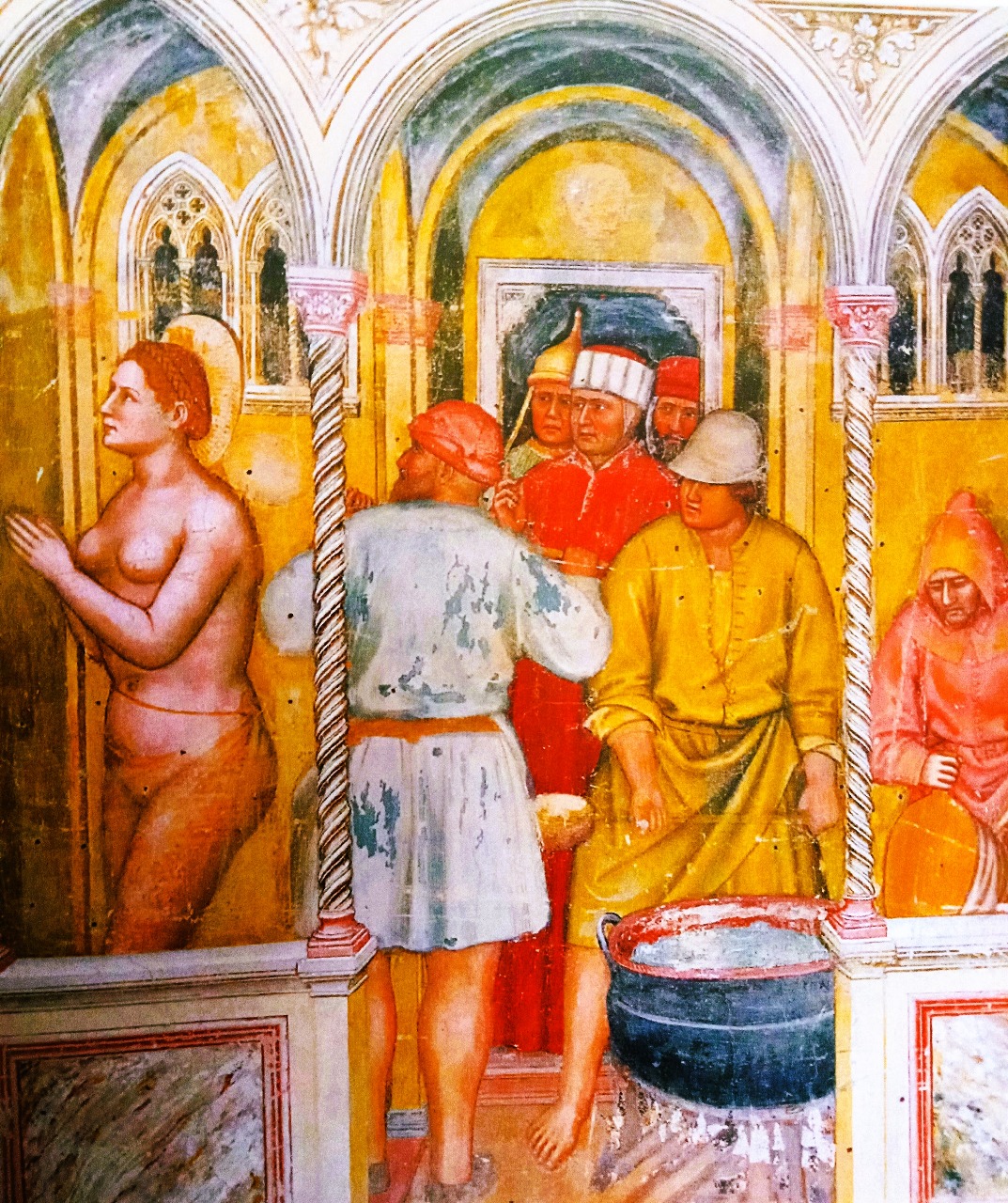

Everywhere in late medieval Italian art we encounter a stoic calm, a quiet affirmation of sad fates as saints are confronted with human wickedness and their impending martyrdom. A naked Saint Lucia calmly awaits being boiled in a cauldron with burning oil, which under the professional instructions of a judge is methodically prepared by obviously insensitive, but quite ordinary henchmen.

With the same pious acceptance, St. Lawrence is laying on a rack stoically awaiting to be grilled, while his executioners like a team of cooks are busying themselves with preparations for the barbecues as if they were part of a perfectly normal, daily routine.

Executions appear as if they were solemn, sacred rituals with serious participants. Like here where Saint James is to be beheaded. A father carefully removes his curious son from what is to become a bloody spectacle.

With total calm, Jesus rejects an anmalistic, terrifying Tempter’s suggestions: Vade retro, Satana! Get behind, Satan!

And when the devil had ended all the temptation, he departed from him for a season.

On a fresco by Spinello Aretino, a cool monk is confronted with a horrible looking devil. Completely unafraid, he looks the monster straight in the eyes.

The child Jesus also seems to possess a sangfroid peace, far aloof and much more mature than what is common among any other children of his age.

He is a nice kid. On several frescoes and paintings, he tenderly and comfortingly strokes his mother’s cheek.

When an aged Virgin Mary has been forced to watch the suffering of her beloved son, she gently receives him while Joseph of Amaltea gently lifts the dead Savior down from the cross.

The virgin mother then places her son’s emaciated and cruelly tortured, lifeless body into a sarcophagus.

It would be a while before a sorrowful Mary and a tortured Jesus in a Pietá were transformed and portrayed as a couple of beautiful young people.

The painting above of the dead Jesus and his elderly mother comes from an altarpiece in a now ruined church in Bologna. When its unknown master, called Jacopino di Francesco, portrayed a martyred, emaciated Jesus, he worked within an already well-established tradition in which Jesus was portrayed as an ordinary human being, as one of us; a lonely, suffering individual.

The intensity in di Francesco’s depiction of the dead Jesus and the signs of the torture he had been forced to endure may be compared to the visions of his contemporary Den heliga Birgitta, Saint Brigid of Sweden:

Finally, they extended his body on the cross beyond all measure; and placing one of his shins on top of the other, they fastened to the cross his feet, thus joined, with two nails. And they violently extended those glorious limbs so far on the cross that nearly all of his veins and sinews were bursting. Then the crown of thorns, which they had removed from his head when he was being crucified, they now put back, fitting it onto his most holy head. It pricked his awesome head with such force that then and there his eyes were filled with flowing blood and his ears were obstructed. And his face and beard were covered as if they had been dipped in that rose-red blood. And at once those crucifiers and soldiers quickly removed all the planks that abutted the cross, and then the cross remained alone and lofty, and my Lord was crucified upon it.

The entranced Birgitta Birgersdotter (1303-1373) became through her ”inner sight” a hapless witness of how Jesus’

fine and lovely eyes appeared half dead; his mouth was open and bloody; his face was pale and sunken, all livid and stained with blood; and his whole body was as if black and blue and pale and very weak from the constant downward flow of blood. Indeed, his skin and the virginal flesh of his most holy body were so delicate and tender that, after the infliction of a slight blow, a black and blue mark appeared on the surface. At times, however, he tried to make stretching motions on the cross because of the exceeding bitterness of the intense and most acute pain that he felt. For at times the pain from his pierced limbs and veins ascended to his heart and battered him cruelly with an intense martyrdom; and thus his death was prolonged and delayed amidst grave torment and great bitterness.

Visions of times gone by, or a parallel fantastic reality, were common at the time and the mastery of the greatest Christian visionary of them all has since then never been surpassed – the incomparable Dante Alighieri (1265-1321).

In his Divine Comedy, Dante excels in a great artist’s rich and extremely skillful performance. His mighty work is a living tableau which in a stylistically impeccable way and in great detail presents the abominable fate awaiting each sinner within an immensely vast, underground realm. In Dante’s Inferno and Purgatorio, an unimpeded divine justice impose harsh and eternal punishment on every condemned soul, entirely in accordance with the nature of crimes committed during her/his mortal existence. Dante’s Inferno, Purgatory and Paradise have been harmonized and calibrated to the smallest detail, they are all part of a highly efficient bureaucratic organization. Every soul, sinful as well as righteous, has within this divine, detail-controlled Cosmos be allotted its proper and carefully prepared place.

Dante was an innovator, and to a certain extent also a creator of the Italian language and his work is illuminated by an almost perfect control of all the artistic-literary means of production available to him. The wealth of imagination and the virtuoso language treatment leave nothing to be desired and he was well aware of his own mastery – just like his contemporary friend and equal in the realm of painting, Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337).

In 1810, a previously over-painted fresco by Giotto was revealed within Magdalena’s chapel in Florence’s Palazzo di Podestà. The Podestá was in medieval Italian cities the executive body of municipalities and was in charge of carrying out death sentences. In Magdalena's chapel, criminals awaited their execution could watch walls covered with frescoes, depicting what awaits us after death - Hell, Purgatory, or Paradise. Among the crowds of Paradise a man could be distinguished who nowadays has been assumed to be a portrait of Dante Alighieri, made by his good friend Giotto.

However, this ”portrait” does not really correspond to the description that Boccaccio (1313-1375) gave of the great author in his Trattatello in laude di Dante from 1347.

Our poet was of middle height and after he had reached mature years he walked with somewhat of a stoop; his gait was grave and sedate; and he was ever clothed in most seemly garments, his dress being suited to the ripeness of his years. His face was long, his nose aquiline, his eyes rather large than small, his jaws heavy, with his underlip projecting beyond the upper. His complexion was dark and his hair and beard thick, black and crisp; and his countenance always sad and thoughtful.

Dante mentions Giotto in Purgatorio’s eleventh song. Accompanied by Virgil, Dante has now come to a ledge where crowds of naked men and women carry heavy boulders which are ”pushing down their arrogant necks”, a punishment for having thought themselves to be better than their fellow human beings. During their mortal lives these victims of great pride had been whipped onward by a constant desire to become famous and admired. Dante seems to recognize a man who stumbles under his heavy boulder burden. Dante leans forward and talks to him and finds out that the poor souls is the by now forgotten book illustrator Oderisio Agubbio, whom Dante got to know in Bologna. Oderisio regrets sacrificing his life’s happiness to the intoxication of pride, only to after his death to discover that other even better artists have overshadowed his once so great fame:

Oh, what vainglorying in human powers!

How short a time the green lasts on the height

unless some cruder, darker age succeeds.

Once, as a painter, Cimabue thought

he took the prize. Now Giotto is on all lips

and Cimabue’s fame is quite eclipsed.

[…]

The roar of earthly fame is just a breath

of wind, blowing from here and then from there,

that changes name in changing origin.

Both Dante and Saint Brigid were harassed by the demon of pride. In Brigid’s visions Christ called her his very ”special darling and confidant”, while the Virgin Mary exchanged confidences with her. Brigid’s commonly used epithet for herself was ”Bride of Christ”. However, despite this almost limitless pride no one can deny that Dante and Brigid were endowed with exclusive strengths and genius. Dante could actually be quite harsh on himself, pointing out his excessive pride as a threat to the salvation of his soul, while Saint Brigid through her visions of Christ could condemn that she had not previously distanced herself from ”carnal lust” stating that

for the sake of your fornication you would be worthy of having all your limbs loosened from their joints, that your flesh should be consumed by rot, that your skin would blister from boils, that your eyes would be torn out, that your mouth would be twisted out of its joints, that your hands and feet would be cut off and all limbs of yours be mutilated, without any interruption.

The bodily focus and drastically detailed descriptions of torments are typical of Brigid, who thtough her visions often was allowed to witness how her enemies and opponents are tormented. While her confessors in Latin wrote down what their admired protege had seen and heard, she herself wrote in Swedish down her revelations with an elegant and easy-to-read handwriting, usually in accordance with a recurrent pattern - an accurate, ”overheated” description of the ”revelation” followed by a cumbersome interpretation. An example is when she portrays a close acquaintance of hers who turned out to have been a false friend. In a vision his ”true self” is revealed in a horrifying manner:

This man appears to the people to be a well-dressed, strong and attractive man, who is brave in his Lord’s battle, but when his helmet is removed from his head, he is ugly and disgusting to look at and it is useless for work. His brain is seen to be bare. His ears are on his forehead and his eyes are in his neck. His nose is dissevered and his cheeks are altogether sunken like those of a dead man. On the right side his chin and half of his lips have all fallen off, so that nothing is left on the right side except his throat which is seen to be all uncovered. His chest is full of swarming worms and his arms are like two snakes. The most poisonous scorpion lives in his heart. His back is like burnt coal. His intestines are stinking and rotting like pus-filled, unclean flesh. His feet are dead and useless to walk with.

Then follows an in her usual manner rather far-fetched interpretation of every detail of the individual parts of the vision. According to Bridget worldly phenomena generally have several meanings. In this way she reminds of anothrt Swedish mystic and visionary Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), who saw correspondences everywhere, i.e. that for him everyday concepts and events hid reflections of a higher, spiritual meaning. Bridget also reminds of Swedenborg through her manner to step in and out of her revelations, though they might also come to her with such a force that those around her took them to be similar to epileptic seizures

Like Swedenborg, Bridget was also an extremely productive writer and a practical person, well versed in politics and able to eloquently express herself in both Latin and Swedish. As with Swedenborg, Bridget’s visions oscillate between obnoxious depictions of Hell (often complete with disgusting odours), as well as clear-minded speculations and moral sermons. Like Swedenborg, Bridget was often met with ridicule and contempt, though at the same time she could be sincerely admired. When she impressed Queen Eleonora of Aragon in Cyprus, the monarch’s Dominican confessor muttered: “The bitch is crazy!” Perhaps Bridget had some awareness of her own arrogance and knew that others might regard her piety as narrow-minded and even hypocritical. In a revelation, a defeated Devil leaves a heavenly courtroom where Bridget successfully had acquitted her reprehensible son Karl from eternal damnation, on his way out Satan shouts and rages at Bridget while calling her “that damned sow!”

And so it has continued throughout the centuries. Admittedly Bridget was canonized early on and is now one of the Catholic Church’s six official patron saints. However, Luther called her die tolle Birgit, the crazy Bridget. The great Swedish author August Strindberg hated her, perhaps because this seriously misogynistic writer harbored a certain concern, or even fear of powerful and outspoken women. He described the saint as “domineering, ambitious and unsympathetic.”, an “rambunctious cow” and “nasty bitch".

Like Dante's masterpiece, Brigid’s Revelations received great and almost immediate attention, and their descriptions of a spiritual reality had a great impact on the artists. Saint Brigid may therefore earn her rightful place in an exposition of Italian fourteenth-century art. Between 1349 and 1373 she lived in Rome, with the exception of a couple of longer pilgrimages, including one to Palestine.

Her Revelations became an inspiration to several northern Italian masters, not the least Filippo Lippi and Michelangelo. However, her influence waned over time while Dante’s survived. For example, so are William Blake’s unconventional depictions of Dante’s Inferno unparalleled

and Dante has continued to inspire modern artists, such as Georg Grosz, Renato Guttoso and Robert Rauschenberg, just to name a few of the most famous ones.

Dante is certainly the greatest poet, visionary and intellectual of the two, but this comparison cannot detract from the remarkable strength, determination and great influence that Birgitta Birgerson actually possessed. Her visions are certainly different from Dante’s elaborate masterpieces. They were written down shortly after she had left her trance-like conditions and were then edited by herself and her confessors. Her intense revelations are marked by a momentary inspiration. They are whipped up by her distinctive personality and are quite often characterized by a high-pitched obsession, drastic imagery, and a rhythmic dynamic that makes them fascinating reading.

Birgitta Birgersdotter is a driven artist. Her pictorial visions show a peculiar mixture of nature, sincerity, profound biblical knowledge, rich imagination and classical rhetoric, and not least does everyday life occasionally emerge. To the Virgin Mary, Bridget states that “through you the great God became a little laddie” and Jesus flatters Bridget by claiming that her soul “is to me as sweet and pleasant as a cheese.” Even more bizarre parables are when Bridget portrays God as a vodka distiller, or magpie.

After her visionary attacks, Bridget was often quite exhausted and no wonder that her general condition often was affected by vigils, fasting, mortification of the flesh and constant pilgrimages to near and far. However, she seems to have had an iron physique and was not at all ravaged by the plague that reaped so many around her. She made her journey to Rome in the midst of the Black Death and during her arduous trek through Europe she encountered everywhere rotting corpses and people infected by boils and famine. Death reigned unconstrained and his dance macabre dragged with it people from all walks of life – kings, beggars, priests and peasants entered the dance.

When she arrived in Rome, Bridget’s visions intensified and it is now that her phantasmagorias of Hell blossomed to their fullest. Violence bordering on blasphemy could make Bridget doubt whether her revelations really originated from God. Nevertheless, her divine friends succeeded in convincing her that they were all of heavenly provenance and they kept Satan away from her. God, Jesus and the Archangel Gabriel could assure her that the revelations she wrote down all had a celestial source. Like here on a fresco that Johannes Rosenrod in 1437 painted in the small Swedish parish church of Tensta where he lets an angel hit a cudgel on the head of the Devil when he is in the process of trying to provide the writing Bridget with false revelations.

As with other visionary mystics, such as William Blake and the Swedish mystic, visionary and church founder Emanuel Swedenborg, Brigid’s revelations were profoundly personal. Like Dante, she allows her perceptions, prejudices and condemnations of contemporary personalities intrude on her visionary view of the world and populate her nasty hell with a multitude of opponents whom she with ill-concealed gloat made suffer horrible torments. Her Hell is far from being as well-organized as Dante’s Inferno. Her devils roar like madmen while they with claws and fire forks tear at and sting hearts, stomachs and feet of sinners. They squeeze their victims, wound them and crush their joints between their pointed, predatory teeth. Bridget observes how a demon brutalizes a couple who had ”entered marriage against church ordinance” so fiercely that ”everything in the end looked like a single, bloody ball of yarn.”

One of the most horrendous depictions of hellish suffering is when Bridget at the request of a rich and noble lady described how her dead daughter and deceased mother suffered ”on the other side”:

the mother appeared to be crawling out of a black well of utter darkness. Her heart was torn out, her lips cut off and trembling, her teeth shone white and long and all of them rattled. Her nose was eaten and the eyes had been excavated from their sockets and were by two tendons hanging down her cheeks … The chest was seen cut open, filled with long worms … And a long, large snake moved from the bottom up, through the stomach, curling its head and tail like a bow, constantly meandering around the intestines like a wheel.

Allusions to Brigid's visions can generally be traced through comparisons with her written revelations. For example, Filippo Lippi's, and several other artists, depictions of the birth of Jesus have obviously been inspired by Brigid’s Revelations:

then the Virgin knelt with great reverence, putting herself at prayer; and she kept her back toward the manger and her face lifted to heaven toward the east. And so, with raised hands and with her eyes intent on heaven, she was as if suspended in an ecstasy of contemplation, inebriated with divine sweetness. And while she was thus in prayer, I saw the One lying in her womb then move; and then and there, in a moment and the twinkling of an eye, she gave birth to a Son, from whom there went out such great and ineffable light and splendor that the sun could not be compared to it. Nor did that candle that the old man had put in place give light at all because that divine splendor totally annihilated the material splendor of the candle. And so sudden and momentary was that manner of giving birth that I was unable to notice or discern how or in what member she was giving birth. But yet, at once, I saw that glorious infant lying on the earth, naked and glowing in the greatest of neatness. His flesh was most clean of all filth and uncleanness. I saw also the afterbirth, lying wrapped very neatly beside him.

In Lübeck, in 1492, Bartholomeus Ghotan printed a luxurious edition of The Revelations of Saint Bridgit (Bridget had been canonized already in 1391). This edition is richly illustrated with excellent woodcuts, among the illustrations we find a picture of the nasty vision with the poor mother who with her hollowed-out eye sockets, while the daughter is tormented in Purgatorio, crawls out of a black well, which is in fact the Devil’s oral cavity.

An abhorrent scene that when I read the revelation made me remember a ghastly episode in Hideo Nakata's film Ringu in which a female demon climbs the wall of a deep well until she emerges to haunt us.

Despite occasional images of devilry, martyrdom and death, it is generally heavenly bliss and beauty that is embodied in northern Italian, Gothic paintings.

Peace and quiet, paired with an exuberant narrative joy and empathetic depictions of people's emotions, meet us in Giotto’s art. I think it was in 1965 when I and my father visited Capella degli Scrovegni in Padua. I was unprepared for the dizzying feeling that met me there. Far stronger than the one I experienced when I later visited the Sistine Chapel. At that time, I hardly knew who Giotto was – the blue-tuned walls with their narrative boxes, almost like strips in a comic book, of which each presnted a visualization of a dramatically depicted biblical scene; sharp, expressive, beautiful, vivid and often completely unexpected.

I was deeply moved by all the sorrow and despair surrounding the dead Jesus.

But what has followed me through life, ever since I first saw it, is Judas’ kiss. How Jesus with total calm watches how Judas wraps a saffron-yellow cloak around his friend and master and with pouting lips approaches his face to his to give him the fateful kiss. Without hatred, contempt or surprise, Jesus looks at the man whom future generations came to regard as the incarnation of a traitor. Was he really that? Did not Judas act on the advice of God and Jesus? The surrounding men are not the same grotesque creatures that Jesus’ captors are usually portrayed as. They are ordinary people taken in by the seriousness of the moment:

Now he that betrayed him gave them a sign saying, Whomsoever I shall kiss that same is he: hold him fast. And forthwith he came to Jesus and said, Hail master; and kissed him. And Jesus said unto him, Friend, wherefore art you come? Then came they, and laid hands on Jesus, and took him.

On another visit, much later, it was another kiss in the same chapel that impressed me. Joakim's meeting with his wife Anna at the gate of Jerusalem, when he knows she will give him a long-awaited child – Virgin Mary. Two mature people’s tender kiss. The warmth between a married couple who has known each other for a long time, who understand and love each other. Like so many of his contemporary artist colleagues Giotto was a great connoisseur of people’s better sides; quiet conversations, calm and mutual respect.

The experience of Capella degli Scrovegni made a deep impression on my young, almost childish mind and I have the two times when I returned there felt almost the same shudder as the one I felt when I first saw Giotto’s frescoes. Almost … since the first time I visited the chapel I was there all alone with my father and it was all new to me. The other times there was a lot of people around and by then I know all the pictures beforehand, having seen them in several books. However, looking at pictures in books is not at all the same thing as standing in front of actual works of art.

A feeling similar to the one that affected me in Padua fifty-five years ago, took hold of me when I ten years later with my friends during an Inter-rail trip in Siena had ended up in front of Duccio di Buoninsegnas Maestà. It is almost painful to be confronted with such mastery and utterly futile to try to explain what happens at such a confrontation. Each approach to an explanation turns into embarrassing chatter. It is as if the sight is united with bodily functions. Perhaps it is this that is called the Stendahl Syndrome – ”a psychosomatic disease that can cause rapid heartbeat, dizziness and hallucinations when an individual is exposed to art.”

In his travel book Rome, Naples et Florence, Marie-Henri Beyle wrote (he used the pseudonym ”Stendahl”):

I was already in a kind of ecstasy at the thought of being in Florence, and the vicinity of the great men whose tombs I had just seen. Absorbed in the contemplation of the sublime beauty, I saw it up close, I touched it, so to speak. I had arrived at that point of emotion where the celestial sensations given by the fine arts and passionate feelings meet. When I left Santa Croce, I had a heartbeat, the so-called nerves in Berlin; life was exhausted in me, I was walking with the fear of falling.

The English author Julian Barnes seems to have written the book Nothing to be Frightened of as a conjuration against his great fear of death. With a mixture of humor and deep seriousness, Barnes presents a number of anecdotes and descriptions written by a number of writers, artists and musicians who have either been tormented by their fear of death, or shrugged their shoulders at such “delusions”.

Barnes does not believe in an afterlife. He is not at all religious, though that does not hinder him from being tormented by the fact that if he were, he might not harbor his crippling fear of death. However, he finds confidence and calm in music. He is captivated by the grandeur, the boundless genius of religious masterpieces such as Bach’s and Händel’s Masses, or Mozart's Requiem.

Personally, I imagine that I can hear God speak in Bach’s music, especially in his H Minor Mass and in the incomparable choir Wir setzen uns mit Tränen nieder from the St Matthew Passion. Play it at full volume, in the solitude of a darkened room, or even better ... listen to how it is sung and played under the soaring vaults of a Gothic cathedral. How the music rises and rises, sweeps forward in heavy swells, caresses, calms, fills the space and your interior, calms you, lifts, comforts. This is the indescribable music of the spheres. Here is God. Apparently, Bach was of the same opinion, in his preserved manuscripts we find by a written-down piece of music his comment: ”A splendid demonstration [Beweis] that music has been mandated by God’s spirit.”

It is when Barnes writes about the presumed presence of God in certain music that he comes across Stendahl, "the happy atheist" who found solace in art. Aesthetics was almost a religion for Stendahl.

The decisive event in Stendahl’s life was the above-quoted experience in Santa Croce’s Cappela Niccolini, which houses some incomparable frescoes by Giotto, such as a tender depiction of the monks’ grief at the death of St. Francis.

The constantly curious and inquisitive Barnes scrutinised Stendahl/Beyle’s diaries for another description of the dizzying experience, but found no mentioning of Giotto, instead Beyle writes about Bronzino and Volterra and it seems as if the “life-changing” episode in Cappela Niccolini was something he elaborated several years later. “But,” Barnes wrote, it does not mean that the young Marie-Henri Beyle in the Florentine chapel had not been overtaken by strong emotions and that he was ”an exaggerator, a fabulator, a false memory artist”. Barnes speculated that it may not have been the mere looking at the exquisite frescoes that caused the dizzy spells. Tired after a difficult journey, deeply moved by finally being able to face masterpieces that he had previously had only seen in the form of black and white reproductions, and not least by sitting on a pew for a long time with his face lifted towards the ceiling frescoes could make anyone stiff in the neck and dizzy in the skull. No, Stendahl/Beyle’s testimony could not convince Julian Barnes that art might convey connections with an elusive, divine reality.

Barnes later wrote that the young Beyle’s experiences had later probably been taken care of and gilded by his literary persona –Stendahl: “If Beyle went through something, it was changed by Stendahl, because in the world of fantasy it is enough with some extra drops water to fill the bucket.”

That a morbidly increased sense of beauty can be life-changing and downright dangerous was masterfully portrayed by Yukio Mishima in his The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. The novel is based on a true story about a young Buddhist monk, Hayashi Yōken, who in 1950 burned down the famous Rokuon-ji Temple in Kyoto. Hayashi suffered from stuttering, inferiority complexes and an increasingly overwhelming anxiety about mind-boggling beauty, something that eventually turned into an urge to befoul or even destroy it. Mishima was well acquainted with the actual story, he did for example on several occasions talk to the imprisoned Hayashi, and his novel is largely based on what was known about Hayashi’s tormented personality and how his crime was staged.

Hayashi, who in the novel goes by the name Mizogushi, was tormented by the sublimity of beauty, which in his twisted mind distanced him from a life in which he had to suffer contempt, loneliness and imperfection.

In Italian Late Gothic art, extraterrestrial angels look from their heavenly abode sympathetically down on a suffering humanity.

Or gather around the celestial thrones of God and the Virgin.

Together with Saint Peter, they receive the happy and blessed people who have earned their right to the joys of Paradise.

Angels hover over the earth while God, carried by angels, separates land from sea.

However, one of them flew down to earth to announce to the Virgin Mary that she would give birth to the Son of God.

When Simone Martini's portrayed the fateful occasion, Gabriel’s mantle still seems to wave in the wind after his rapid journey through space.

We see people subjected to the divine power and how they intensely pray for grace and help.

Angels calmly fight the forces of evil.

Heavenly hosts are mobilized with calm determination.

Empathy with human suffering, balance and dynamics is not limited to the art of painting, but also present in contemporary sculptures.

An open, tolerant curiosity prevails.

The artists do not underestimate the depiction of our earthly existence. They pay attention to people’s interaction, their mutual relationships and willingness to seek and understand.

Cardinal Nicholas of Rouen is intensively studying a text.

while St. Nicholas’ attentively listens to what an angel whispers in his ear.

We sense the same interest as we witness how Pope Innocent III leans forward to listen to Saint Francis.

Another frame in the suite of frescoes in Assisi depicts how Innocentius dreams of how Francis supports the Papacy’s sinking Church.

The reactions of some Orientals as they witnessed the martyrdom of Franciscan monks:

A pair of monks’ are wondering about one of Francis' miracles:

Wonder and doubt while witnessing St. Martin’s resurrection of a dead boy:

A couple of riders watch Jesus’ crucifixion.

Pope Sylvester is consulted and asked to intervene to help Romans to get rid of a nasty dragon, which he then seeks out and calmly, gags to prevent it from polluting the atmosphere with its deadly breath. The whole thing has the character of a kind of church rite.

The artists are not content with depicting a group of individuals, they also make an effort to portray each person’s distinctive character.

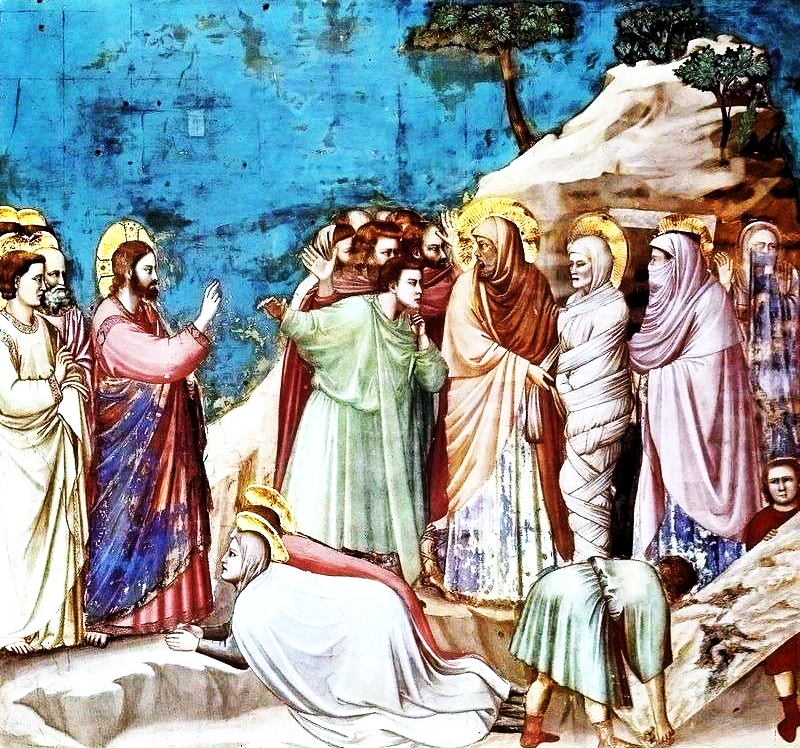

This often happens in a dramatic way, for example when Giotto shows the reactions when the dead Lazarus is taken out of his tomb to be brought to life by Jesus.

In a series of pictures, Jesus’ reactions change in accordance with the events and are reflected in his facial expressions. As when he is brought before the judges of Sanhedrin and reveals the anxiety of a blameless prisoner.

The gestures are also telling. To men have witnessed the exdcution of a saint:

Virgin Mary draws her child's attention to St. Francis’ presence.

Or she holds her hands to her chest as she reverently and attentively receives the heavenly message of her impending pregnancy.

A maid makes a dish-washing man aware that a dinner party is asking for his services.

A shepherd is awakened from his slumber by the appearance of an angel. His friend, however, continues to sleep.

A married couple takes a joint bath before going to bed, while the wife tenderly places one hand on her husband’s shoulder. A little laterhe removes the bed-sheets next to his naked, sleeping wife.

Saint Peter's concerns for the future are reflected in his face as he follows Jesus during his triumphant entry into Jerusalem.

A few moments later we see Peter in the courtyard of the temple warming his bare feet by a fire. With an irritated gesture and a dismissive expression, he denies the accusation that he is one of Jesus’ companions.

Another example of the drama artists manage to fit into into the limited space of their frames, while preserving gestures and vivid movements is Vitale da Bologna’s presentation of how Saint George fights the dragon. His horse rises and turns its head as the saint hinders its stride by tightening its reins, as he presses his lance between the dragon’s yaws.

Consider the dramatic development of events and the joy of storytelling within a single image from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s series of depictions of Saint Nicholas’ miracles.

A dinner party is disturbed by the arrival of a stranger. A serving lady gets noticeably annoyed by this break in the dinner and apparently asks a boy to look for whoever showed up.

The boy finds that it is a pilgrim asking for alms.

The falsely pious man, however, turns out to be a devil in disguise, his bird-claw-like feet reveal him, and under the stairs up to the dining hall he strangles the poor boy.

The mother mourns by her child's deathbed. But then something happens, which is first noticed by the monk who also finds himself in the room. The boy is brought to life!

The reason is that Saint Nicholas in his heavenly abode from his mouth and one hand has sent down life-giving rays that resurrect the boy.

Other miracles show how one of the ropes on which a cradle is strung to the roof to the great despair of the wet nurse breaks and throws the baby out on to the veranda, where it lies lifeless while blood is streaming out of its crushed skull. But one lady witnessing the catastrophe prays to Saint Nicholas, who from his heaven raises the child to life.

Equally dramatic is when a board comes loose from a balcony after a child standing on a stool has leaned against it. He falls helplessly to the ground. But even here San Nikolaus intervenes, he flies down and prevents the boy’s fall. At the same time, he makes with one hand sure that the broken board does not hit the falling child. The unharmed boy is taken care of, saved from a certain death.

This combination of everyday events and miracles is depicted time and time again. We get to see how Maria in her room is visited by Archangel Gabriel, who comes flying in through a window, while her maid unknowingly is sitting spinning just outside the door.

During the wedding in Canaan, a portly cupbearer takes a well-seized sip of the wine while the Virgin with a discreet gesture seems to ask him to save something for her as well.

A stern looking housewife hands to a maid something covered with a patterned linen cloth.

A similar cloth cover some items carried into a room where Mary's mohter is giving birth.

Untouched by the miracles taking place around him, a man sits undisturbed by his fishing rod.

Another man lies down on the ground to drink from a spring that St. Francis just has produced from a rock.

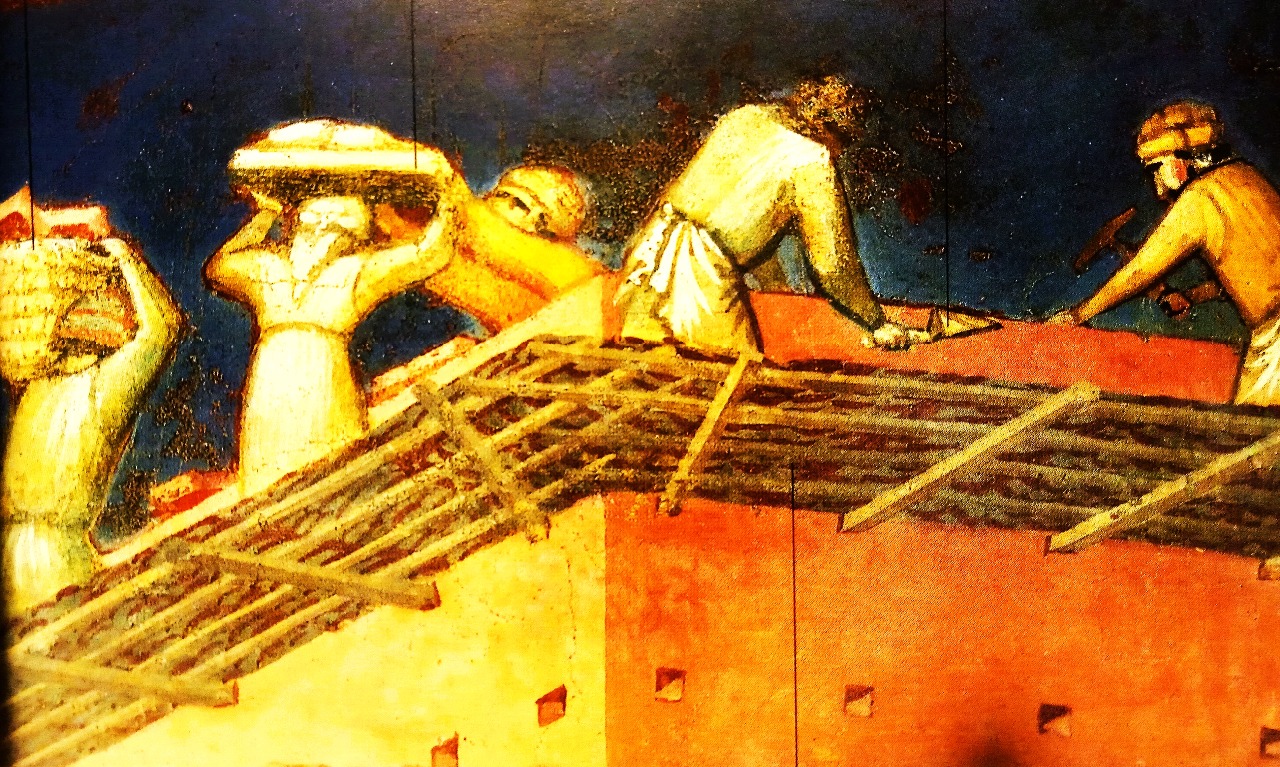

Bricklayers and handymen are busy working on a wooden scaffolding.

Below them, a man with a donkey has stopped in front of a shoemaker’s shop looking at boots that are hung behind the man who hands him a shoe. In the house next door, a group of attentive students are taught to a teacher placed on a lectern above them.

Another sign of the curiosity and thirst for knowledge that is often portrayed with great empathy by Italian thirteenth-century artists, for example on the reliefs at Professor Pietro Cerniti’s sarcophagus in Bologna.

A common subject is bustling ports and distant ships.

We see how pious passengers travel safely across the oceans, while sailors are active around them.

Even in these boats we find people involved in lively discussions.

A city with people building, improving, buying and selling.

In the cities there is also entertainment; dance and music:

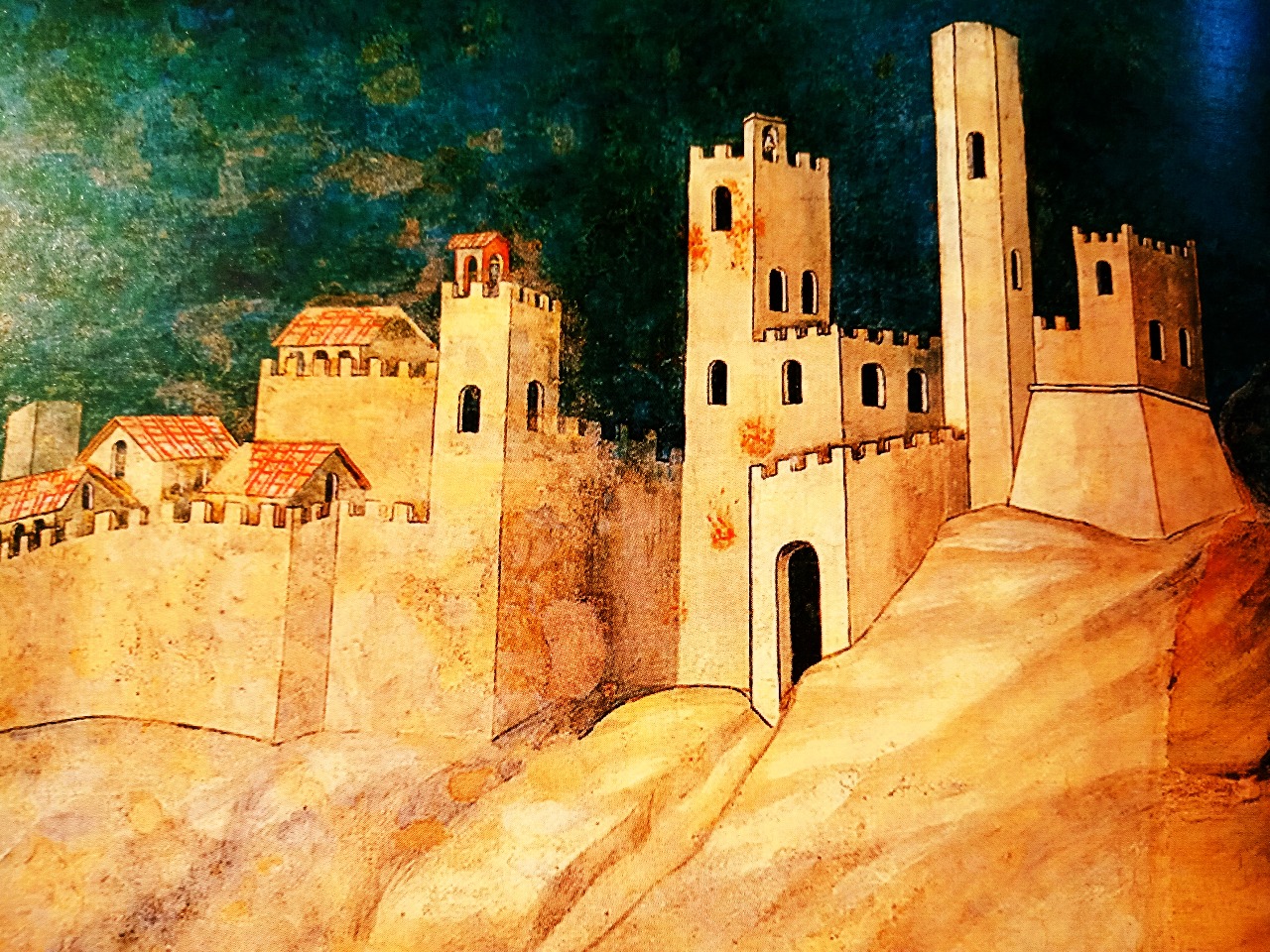

It is a time when cities are emerging in northern Italy, becoming the center of cult and business acumen. The artists seem to be particularly fascinated by these new urban landscapes.

Fresco after fresco depicts cities and castles.

Their abstract character has fascinated modern artists such as Escher and Kanoldt.

My childish mind associates them with the Duckburg that was portrayed in my childhood beloved Donald Duck Comics.

I remember how some of these comic as an appendix had clip charts, which I cut out and joined together into small models of Duckburg. I had one close to my bed.

Not only cities, but also nature is often present in the artists’ pictures. Perhaps for the first time in European art, landscape paintings are beginning to play an increasing role and like images of saints and angels these landscapes are also presented in such a way that they seem to carry a mysterious message, characterized by calm and harmony. They are often empty of people.

However, we also find people surrounded by and influenced by the forces of nature. In Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s depiction of “a bad government and its consequences,” we find a man who walks through a snowstorm.

Hermits can often be depicted as if they part of the surrounding nature. Like Saint Benedict who according to legend, spent much of his life naked in a cave under Subiaco’s cloister, fed by a raven who brought him from the refectory above him.

Pictures might also be about people who look at natural phenomena through which they can sense the presence of God as the men who in a fresco by Andrea Orcagna marvel at a solar eclipse.

In Pietro Lorenzetti’s depiction of Jesus’ capture, the moon rises behind a hill in the olive grove of Gethsemane.

A man collects leafy branches to cover the path leading Jesus into Jerusalem.

In one hand, the baby Jesus hugs a European Goldfinch. A quite common accessory due to a legend that became common at the time – when Jesus was staggering under his cross to Golgotha a finch flew down to pluck off spines from the crown of thorns that had been pressed onto his head. Some of Jesus’ blood dripped onto the finch’s head and do ever since adorn the bird as sign of its empathy, though thorns and thistles are part of its natural diet.

Strong impressions we obtained early in life are probably the ones that stay the longest with us. I remember well some primary school lessons with Maj Ahle. At that time, there was a lot of Lutheranism in the Swedish school. Morning gatherings with organ music and hymn singing, we got to learn several hymns by heart. I had nothing against that. I was fascinated by fairy tales and everything mysterious. Something that makes me remember the story about Robin Redbreast from Selma Lagerlöf’s Christ Legends, which Mrs. Ahle once read to us.

Selma had recently, dazed by her Italian experiences, returned to her beloved Swedish mansion Mårbacka and that was where she wrote charming legends inspired by the rich fairy tale flora of Catholic, Itaialn folklore. With a light hand, she humorously and insightfully retold these legends, which she well knew were a magical manner of expressing truths in a way that no science could do.

The story about Robin Redbreast begins with God creating the animals and it is clear that Selma does not tell her story about a goldfinch because:

It happened one day, when our Lord sat in his paradise painting little birds, that the colours in his paint pots gave out. The goldfinch would have been without colour if our Lord had not wiped all his paint brushes on its feathers.

Towards evening it occurred to Him to create a small gray bird, but then there were no colours left. He named the bird Redbreast, and of course the little creation asked:

– Why should I be called Redbreast, when I am all gray from the bill to the very end of my tail? Why am I called Redbreast, when I do not possess one single red feather?

He received the answer that he would be worthy of his name after he had deserved it. The bird then did everything in its power to get its red breast;. He built his nest among thorn bushes with the hope that his breast would be torned so it turned red, or that the red colour of roses would leave an impint on his chest. He fell in love so violently that he hoped that the glow of love and tenderness would colour him red. He sang high, beautiful, tones in the hope that the marvellous sound of his song would burst his chest and redden it by blood. The little bird had also hoped that his chest would have turned red thorugh his courage and fighting spirit. However, everything was in vain, he remained the same gray little bird.

To his great dismay, the little bird one day saw a tormented man dragging on a cross on his way to his execution, and he became terrified of the evil of men:

– How cruel human beings are! It isn’t enough that they nail these poor creatures to a cross, but they must place a crown of piercing thorns upon the head of one of them. I see that the thorns have wounded his forehead so that the blood flows, and this man is so beautiful and looks about him with such mild glances that everyone ought to love him. I feel as if an arrow were piercing my heart when I see him suffer!

The bird’s emotions oscillated between anger and pity. He would liked to have been an mighty eagle able to drag out the nails from the tormented man’s hands and feet and with his strong claws and pointed beak chase away his tormentors. But, in his helpless weakness, the tiny bird found no other solution than to circle around the dying man’s head while wondering what he could do to alleviate his suffering. He gathered courage and with his beak he pulled out a thorn that had penetrated the crucified man’s forehead, gratefully he lifted his scarred fasce toward the bird and said:

- For the sake of your mercy, you have now won what your family has been striving for since the creation of the world.

The bird sat down on a cross arm and looked down at its on which a drop of blood had fallen, it has dried and the breast feathers now glowed a rust red colour and so they have constinued to do for with all his descendants.

The beautifully told tale is reminiscent of the collcetions of naïve descriptions of the life of St. Francis, Fioretti di San Francesco, The Little Flowers of St. Francis, written by the end of the fourteenth century and where we find ann earlier told story of how San Francisco preaches to the birds.

A story that has inspired a lot of artists, not the least Selma Lagerlöf’s Swedish contemporary, John Bauer.

God’s Little Pauper did in his Laudes creaturarum pay tribute to God’s wonderful creations:

Be praised, my Lord, through all your creatures,

especially through my lord Brother Sun,

who brings the day; and you give light through him.

And he is beautiful and radiant in all his splendour!

Of you, Most High, he bears the likeness.

Praised be You, my Lord, through Sister Moon and the stars,

in heaven you formed them clear and precious and beautiful.

Praised be You, my Lord, through Brother Wind,

and through the air, cloudy and serene,

and every kind of weather through which

You give sustenance to Your creatures.

In spite of their veneration of nature and interest in human emotion the masters of North Italian Gothic were not any not full-fledged realists. Their art often has an elegant level of abstraction, that may seem unusually modern. Consider for example the buildings behind Pope Sylvester as he descends into the cave of the stinking dragon located below the Roman Forum,

or the hand of Jesus on a Crucifixion by Cimabue,

the powerfully stylized, tomented face of Jesus on a crucifix by Coppo da Marcovaldo,

and two elegant horse heads on a fresco by Pietro Lorenzetti.

However, an ability to abstractation did not prevent an artist like Jacopo Avanzi from creating an astonishingly realistic image of a fallen horse.

On a fresco in Cappella degli Scrovegni we find the sleeping Joakim. An angel will soon wake him up and tell him that he will have a daughter who eventually is going to give birth to a god. Here we find the mastery of Italian Gothic; its stillness and presence of nature, paired with a stoic calm that speaks directly to the soul and mind. An art that, in Schlegel's words, unites the past with both the present and the future, beyond and far greater than our earthly existence. An art in which we sense the marvelous greatness of the Universe.

Joakim is sleeping. He is old. Hope is betraying him. But when he wakes up, he is given a promise of a new happiness, of a changed world. Is it the new art of his time, the one that he himself will initiate and perfect by combining the past with the present and the future that Giotto depicts through the sleeping Joakim?

As I look at Giotto’s nocturnal image of a sleeping old man among waking animals, I think of myself. What does my limited future carry in its womb. A happiness like the one that Joakim experienced in the autumn of his age?

I am now sitting in a basement, looking at pictures and writing this essay. Outside, above me, the sky is high and clear. Spring is on it's way. The cherry trees are blooming and the blackbird is singing.

I remember poems by Gunnar Ekelöf, a mystic who also was a great admirer of Trecento's artists, at the same time as he was irritated by most of the High Renaissance artists, whose works he found to be overly “theatrical and distorted”. After a visit to Florence, he stated that “half of the Renaissance in the Uffizi I do not give a damn about.” However, Ekelöf marveled at the northern Italian Gothic, in which he found a kinship with the mysterious piety reflected by Russian icon painters. In his lyrical suite Opus Incertum, he writes about about the Madonnas of Russian icons and the Italian thirteenth century:

Goddess of unknown origin

old as time

as the origin of man.

You change your view:

Turning away from the child

in fear and foreboding,

you look at the worshiper

seeks his compassion,

again you look at your child,

your heart is moved,

your face softened by pain

Meter Tehou! Eléousa!

The last words allude to “The Virgin of Compassion” an icon variant in which the Virgin tenderly rests her cheek on the Child Jesus, a gesture Elelöf also found among Italian artists.

Ekelöf often wrote his poems in the night and then expresses a longing to be united with nature, to become one with Cosmos, the vast greatness of Infinity. Something he could feel in the art what I have been trying to describe. Maybe it is there in Giotto’s depiction of Joakim's sleep.

It's a starry night.

The air is clean and cold.

In all things the moon seeks

its lost legacy.

A window, a flowering branch

and that’s enough:

No flower without soil.

No earth without space.

No space without flowers.

Alighieri, Dante (1983) The Divine Comedy: Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso, translated by Robin Kirkpatrick. London: Penguin Classics. Alighieri, Dante (2002) La Divina Commedia, a cura di Umberto Bosco e Giovanni Reggio. Rome: Gruppo Editoriale L´Espresso. Bakhtin, Mikhail (1984) Rabelais and His World. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Barnes, Julian (2009) Nothing to be Frigthened of. London: Vintage Books. Birgersdotter, Birgitta (2012) The Prophecies and Revelations of Saint Bridget of Sweden. Altenmünster: Jazzybee Verlag. Boccaccio (2002) Vite di Dante. Milano: Mondadori. Eilenberger, Wolfram (2020) Time of the Magicians: The Great Decade of Philosophy, 1919-1929. London: Penguin. Lagerlöf, Selma (2013) Christ Legends. Edinburgh: Floris Books. Bonniers. Marissen; Michael (2018) ”Johann Sebastian Bach Was More Religious Than You Might Think,”The New York Times, April 1. Mishima, Yukio (2001) The Temple of the Golden Pavillion. London: Penguin Modern Classics. Schlegel, Wilhelm (1968) Selected Ideas (1799-1800): Dialogue on Poetry and Literary Aphorisms. Philadelphia PA: Pennsylvania University Press. Stendahl (2013) Rome, Naples et Florence. Paris: Gallimard.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)