NUMINA: Divine presence in Rome and Guatemala

When I was a kid, It happened that an elderly lady moaned and stated: "There´s much ado about earthly worries." Certainly, quite often everyday life seems to be choking us. Family life's wear and tear nibble on the soul. The darkness of duties, worries and mistakes hovers above us, closes in and threatens our wellbeing.

Outside our Roman apartment lies Parco Cafarella. Actually, it can maybe not be called park, rather it is a piece of nature and countryside in the middle of La Cittá Eterna. The stream Almone flows through a valley passing wooded hills and undulating meadows with grazing sheep. There is a rich bird life, an impressive variety of trees and bushes, a farmhouse with horses, donkeys, hens and peacocks, ancient temples and the remains of a nympheum.

Spring has come and passed, the grass is still thick and lush, flowers spread their fragrance, foliage of trees and bushes is dense, fresh smell of greenery and life. In the Cafarella Park, the weight of everyday life vanishes. As I walk along its gravel paths, I forget time. Like so many times before, I rest for a while by the derelict nympheum. A jet of crystal clear water has for more than two thousand years run forward from an overgrown hill, hiding a cave which is the abode of the nymph Egeria and her sisters, eternally young and seductive, fresh and healthy like the affluent nature they watch over. However, even nymphs might die, just like the nature they protect, though people affirm that Egeria and her sisters still live under their hill.

The marble-covered and mosaic-paved refuge from summer´s stifling heat, which Herod Agrippa once had erected and where his young wife, Anna Regilia was booted to death by a slave, has long been ruined and its remains are now covered with juicy mosses. The water of the pool is opaque and light green, its surface covered by watercress and at the edge blossomed some stately lilies. I came to think of the few snippets of Latin I still remember from the Latin lessons that plagued me more than forty-five years ago:

O fons Bandusiae, splendidior vitro,

dulci digne mero non sine floribus,

cras donaberis haedo,

cui frons turgida cornibus.

Spring of Bandusia, whose crystalline

Glitter deserves our garlands and best wine,

You shall be given a kid,

Tomorrow, horns half-hid.

.jpg)

I am amazed by the fact that I still can quote the poem word by word. My high school Latin lessons mostly consisted of a rough cramming of words and expressions under the strict scrutiny of the austere, but under his rigid surface obviously good-hearted, Docent Hemberg, captain in the Royal Swedish cavalry reserve. I spent a lot of time with Latin, but never understood the grammar and after a year almost everything had blown away. However, what Bengt Hemberg managed to do was to implant a subsisting interest in everything Roman.

Maybe it was because I shared Hemberg's interest in the Antiquity that I finally got quite a good grade in Latin. Without difficulty, I could appreciate Horace's depiction of rural pleasure in the aforementioned verses. With its rhythmically, lively and yet compressed language, Quintus Horatius Flaccus creates the atmosphere of his country-house, located nowaday Licenza, a mile north of Tivoli, outside Rome. A place he often visited to get a rest from the heavy duties of representation and the constant cringing by the feet of powerful magnates, as well as from the dust and stress in Rome. Out in the isolated countryside, Horace was able to enjoy a refreshing freedom, wander through his aromatic groves, drink delicious wine from his own crops, relax by the source of Banusia, and through his windows gaze at Soracte's mountain peak, which in the moonlight shone dazzling white under deep snow.

Horace is one of the few ancient Romans who have told us about himself. In his poems, he has described his appearance, opinions, and habits. Self ironically he characterized himself as a pinguis et nitidus Epicuri, a fat and shiny pig in Epicurus's flock. According to himself, Horace was a small and compact man with a hint of pot belly, nurtured by wine and fine food. He was easily burned by the sun and already as a young man he had grey hair. That Horace described himself as an Epicurean becomes obvious from his writing. According to Epicurus's philosophy, you should strive for a happy and calm life. Free from pain and fear, you should, as far as possible, live off your own assets and enjoy the company of good and honest friends.

Horace stayed in bed until nine in the morning, after that he spent three hours by his writing desk. If he was in Rome and the heat was stifling, he went down to the bathhouse, and if he found himself in the countryside he took a walk across his properties. Then he ate a simple lunch, slept siesta, and in the late afternoon he mingled with the people on Rome's streets, conversed with acquaintances he encountered, perhaps had his future told by a fortune teller, or sat down in a tavern for a snack and wine. While in his country house, Horace often had a jar of wine brought up from his cool cellar – Caecuban, Massicum or Falernian. The latter wine was so strong that it could be ignited, but all wine were mixed with fresh spring water and I can trough my inner vision see how Horace enjoyed his well-mixed wine at Bandusia's source.

Horace happily swung his wine cup among good and boisterous friends and often enjoyed himself in the company of various ladies, especially those who did not require any greater commitments and responsibilities from his side, several of them eventually became immortalized through his poems - Lydia, Leuconoë, Glycera and Lalage. Like many of his wealthy contemporaries, Horace had no qualms about easing his sexual desire in the company of a hapless slave.

The remains of Horace´s villa are still around, and so is Bandusia's spring which actually is not a small source within the woodlands, but a quite impressive waterfall cascading into the remains of a Nympheum.

The lush greenery on the slopes of Colle Rotondo and the valley of Aniene were also frequented by another self-proclaimed Epicurian, the in his mother country immensely popular Evert Taube, who figures on Swedish stamps and bank notes. Most Swedes know several of his songs by heart. It is told that it was on the terrace of the tavern Sibillina in Tivoli that Taube sometime in the 1930s created its alter ego - Rönnerdahl. By that time, Evert Taube had probably begun to tire of his increasingly successful role as entertainer. Portraying himself as a singing sailor and adventurer in books, the radio and amusement parks. He now wanted to reach out to more sophisticated circuits.

“Rönnerdahl”, always mentioned without a first name, is in Taube's poetry much older and more established than his other alter ego – the womanizing swashbuckler Fritiof Andersson. Rönnerdahl is a fairly well-established homeowner, living on an island in the Stockholm Archipelago, but at the same time he is a pensive bohemian, who with some regret evokes his youthful exploits, but now engage himself with painting and innocent courting of young ladies. In one of his memoirs, When I was a young caballero, Taube describes his new stand-in:

Rönnerdahl is a Swedish painter and humanist, well at home among roses and ruins in Rome and among lilies in Florence. He is by me studied in accordance with reality.

In a song we find Rönnerdahl by a waterfall in the Aniene valley, not far from Bandusia's spring, probably by another waterfall located a few kilometres further south, in Monte Catillo´s National Park. While Rönnerdahl is painting, the restaurant keeper´s daughter, the beautiful Sylvia, turns up, boldly and light-hearted she undresses and takes a bath in the clear spring water. Maybe, or maybe not, has she noticed the peeking Rönnerdahl and when he suddenly shows up with a suggestion about painting her as a water nymph she coquettishly agrees to his proposal.

Rönnerdahl was certainly not the first artist who painted bathing, naked ladies in Aniene´s leaf-shaded valley. One of them had been the mentally disturbed German artist Carl Blechen, who had done so a hundred years earlier.

In his song Rönnerdahl's polka from 1954, Evert Taube describes the scene:

Rönnerdahl stands painting in Aniene´s myrtle grove,

where gushing currents are shaded, cool and soave.

Descend from scorching mountain sides, road dusted poet

and behold the colour of a waterfall, the way I know it!

“Rönnerdahl, I´ll give you, in Aniene´s myrtle grove,

my hearty evoe, far from stress and shove!

Your painting makes me grasp, in Aniene´s myrtle grove,

my Sylvia, my nymph, who abandoned me like a dove,

but naked now she stands by a glittering stream!

Sun rays glow on her hair, from your palette they gleam!

Sylvia takes her morning bath in Aniene´s myrtle grove,

a tanned naiad, warm and cheerful by a dusky cove.

While you paint, I´ll sing in Aniene´s myrtle grove,

praising Sylvia's beauty, a river´s treasure trove.”

Trough his "evoe" Taube reveals his classic schooling. It was an ecstatic exclamation that drunken Bacchants burst into while they rushed through the forests during their wild Bacchanals, which were part of the frenzied worship of Dionysos, the Roman Bacchus, god of wine, fertility and extasy. In Euripides´s The Bacchae, the choir sings:

From Asia´s land I come, forsaking sacred Tmolus, in my eagerness to perform my joyous labour for the Roaring One, the toil that bring no toil, crying ´Evoe to the lord of Bacchants.

Tmolus is the mountain Bozdağ in today's Turkey. It was believed that Dionysos had been born there. In “his beastly aspect” Dionysos was called The Roaring One and like the God of the Wild, Pan, Dionysus was sometimes depicted with curving ram horns, but generally he was portrayed as a handsome man with a black beard and crowned by a wreath of oak leaves, being dressed in a full-length, orientally coloured, female himation.

Goat kids were commonly sacrificed to Dionysus, maybe Horace´s sacrifice was dedicated to him, or maybe rather Pan. Anyway Horace cut its throat and let its blood colour Bandusia's source, before having its meet grilled and enjoyed with a tasty wine:

[A kid´s horns] in a bulging forehead forecast love and war ̶

a fine destiny, but not the one in store:

The hot goat people´s son

must with his crimson one

dye your cool vein. No Dog-day in intense

August can touch the sweet chill you dispense

to unfenced, wandering flocks

and the plow-weary ox.

My verse shall make you to a famous spring

known for the ilex on the echoing,

cavern beneath whose shade

your garroulous streams cascade.

After all, the poem makes it clear that there is no god but the source itself which is bequeathed the sacrifice. Like Horace, other Roman poets found themselves immersed by a fresh and vibrant nature. At that time there were no noise from cars and busses, no muzak, no exhaust gases and no electric lights that invaded nature's tranquilizing, all-encompassing presence. You could bring with you a jug of wine, cool it in crystalline, drinkable spring water, while you relaxed on lush, green grass in the cool shadow of tall trees, within the fragrance of new-born greenery, looking up towards an endless clear blue sky, while listening to the birds and the wind's singing in tree crowns, the fresh aroma of spring – that´s all, life itself. Like in a poem by Jorge Guillén

Ser, nada más. Y basta.

Es la absoluta dicha.

¡Con la esencia en silencio

Tanto se identifica!

To be, nothing else. Enough.

That is complete happiness.

The essence of silence,

so much to identify with!

For the ancient Romans, nature was anything but dead, it was even more alive than nowadays. You lived within nature, the healthy presence of breathing life, where you could even be seized by an overflowing feeling of goodwill towards the entire creation; plants, animals and not the least –humans. As Suetonius wrote in one of his letters to Lucilius:

In each and every good man a god (what god we are uncertain) dwells. If ever you have come upon a dense wood of ancient trees that have risen to an exceptional height, shutting out all sight of the sky with one thick screen of branches upon another, the loftiness of the forest, the exclusion of the spot, your sense of wonderment at finding so deep and unbroken a gloom out of doors, will persuade you of the presence of a deity. Any cave in which the rocks have been eroded deep into the mountain resting on it, its hollowing out into a cavern of impressive extent not produced by the labours of men but the result of processes of nature, will strike into your soul some kind of inkling of the divine. We venerate the sources of important streams; places where a mighty river bursts suddenly from hiding are provided with altars; hot springs are objects of worship; the darkness of the unfathomable depth of pools has made their waters sacred.

I learned about that presence while I was interviewing peasants along the border between Dominican Republic and Haiti. Like in bygone rural Europe nature had not yet been besieged by noise, electric light and smelly highways. The houses´ plank walls did not shut out the sounds of the night, the sky was studded with stars. The saturated fragrances and sounds of nature were everywhere, people were part of a nature that was only partially tamed and conquered by human presence. Romilio Ventura told me:

– Sometimes I walk up into the mountains, to the cave under the wooded heights of Nalga del Maco. There I meet God.

According to him, and many others like him, he could pass through the different realms of existence, “like a man walking through sunshine and shadow”, the earth was merely a thin cover above an all-time, life-giving power that springs forth in springs and other holy places, not the least caves, where we after descending into the bowls of earth may sense how The Great Power of God lives and breathes down below our everyday life.

Like the Roman landscape, the Dominican countryside is dotted with holy places. Like ancient Romans, Dominican peasants have marked their sacred places; with altars, coloured bands tied to tree branches, clusters of stones, crosses, or mysterious signs, painted on tree trunks, boulders and rock walls.

In Roman frescoes, we encounter atmospheric, strangely tranquil and enchanted landscapes with altars and ruins, which, as in the Cafarella Park, indicate a divine presence. They testify to the Roman faith in Numina. As everything connected with faith and piety the concept is hard to define. The word is usually translated as "gods", but with the disclaimer that it is rather a "personified power", than a god in its common sense. A Numen could be a thing, like a rock or a plant, an animal, or even be found within a human being. If a man has a Numen, it is that force which constitutes his power, his charisma, virility and even his ability to do things in the best possible way. Each Numen had a very specific, limited task.

Numina may adopt their shape and turn into objects or animals, often snakes, slithering themselves out of the life-giving underworld, source of all budding life. In a frieze within a gym in Herculanum, which like Pompeii was buried and preserved after Vesuvius eruption in 79 AD, we see how a naked boy, with a twig in his hand, approaches a snake swirling around an altar to devour a fruit laying there. Next to the snake it is written Genius huius loci montis, The spirit of this part of the mountain. Obviously the boy is a peasant or shepherd who demonstrates his reverence to a local Numen.

As in the old Nordic peasant communities rådare, rulers, guardians protected, or rather supervised certain places, such as forests, lands, watercourses and mountains. In the Nordic landscapes water sprites were called Näcken, Draugen, Sjörået or Bäckahästen. Overseers of a farmstead and its lands were tomtar, lyktgubbar and vättar. In forests we found Skogsrået, Mosekonen, Vittran or Råndan. In the mountains Bergakungen, Bergsrået and Gruvrået. All these creatures could be both dangerous and beneficent, though they were fundamentally alien, instilled with powers far beyond human understanding. They had to be honoured and respected, otherwise they could become extremely dangerous.

The ancient Romans, and perhaps especially the Empire´s rural inhabitants, apparently believed that everything was populated by mysterious supernatural powers. Fornax made ovens heat up properly, Robigo protected grains from ergot. Laverna protected thieves. Pilumnus fermented bakers' dough. Terminus punished those who did not respect property boundaries. Concordia made city dwellers get on with one another. Liber protected the wine and gave it its accurate strength. Pietas made sure the children respected their parents.

Each phase of pregnancy, birth and childhood was monitored by specialised Numina: Alemona protected the foetus, while Nona and Decima watched over the future mother, Partula ensured that the birth transpired without harmful incidents. Lucina, Candelifera and the Caramines were invoked to protect the child from injuries and diseases. After the birth of the child, thanksgiving ceremonies were organised to honour Inrecedona and Deverra. Cuniva watched over the cradle. Vagitano made children scream. Rumina made sure that the breast milk flowed, Edusa and Potina were summoned to make the child eat properly. Fabulino made it speak. Statulino made it walk, while Abeona and Adeona constantly watched over the child.

Thus, long lists of Numina may be compiled, not least those whose power was circumscribed by specific places, such as the nymph Egeria in the Cafarella Park. A headless sculpture of Almone, rests above the jet of water emerging from the abode of Egeria and her sisters. Almone was the Numen of the stream that watered the valley, home of Egeria and many other Numina.

I walk up a slope next to Egeria's nympheum and soon the landscape opens up. A hill top is covered by Bosco Sacro´s sumptuous trees. Such sacred groves could be found all over the Roman Empire. They were sacer, yet another complicated concept, which originally comes from the Latin word for chopping off and was used to denote something that was divorced/different, both in the sense of being inviolable/protected and cursed, meaning it was dangerous/harmful. The English word holy has the same meaning as sacer and the term exists in a variety of cultures; In Polynesia it is referred to as taboo, in Hebrew it is qadosh and ancient Greeks used the word τέμενος, tenemos to denote a piece of land devoted to the worship of a divinity and it could absolutely not be violated.

Within the History of Religions, such places are often designated by the term hierophany, a concept launched by the influential researcher and author Mircea Eliade, who explained it as a place, or any object or living thing, through which a suprahuman force manifests itself. The German philosopher of religions, Rudolf Otto wrote in 1917 a book about the concept of holyness Das Heilige - Über das Irrationale in der Idee des Göttlichen und sein Verhältnis zum Rationalen, The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and its Relation to the Rational. Like most German humanists of his days, Otto had through a strict and authoritarian schooling been stuffed with Latin and he made the concept of Numen his point of departure. Otto explained that the sensation holiness was a "non-rational, non-sensory experience or feeling whose primary and immediate object is outside the self.” While explaining what he meant Otto became both lyrical and dramatic:

The feeling of it may at times come sweeping like a gentle tide, pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship. It may pass over into a more set and lasting attitude of the soul, continuing, as it were, thrillingly vibrant and resonant, until at last it dies away and the soul resumes its “profane” non-religious mood of everyday existence. It may burst in sudden eruption up from the depths of the soul with spasms and convulsions, or lead to the strangest excitements, to intoxicated frenzy to transport, and to ecstasy. It has its wild and demonic forms and can sink to an almost grisly horror and shuddering.

The very word Numen really means "nodding one´s head", an expression explained by the fact that Numen originally denoted a "divine act", a method used by deity to make its presence known. This makes me remember a strange incident that Armando Caceres once told me about. In the early 1990s, we lived in Guatemala, a strange and violent country, characterized by great injustices once committed against and still perpetrated against its indigenous population. When we were there prejudices against the inditos were still common among the country´s more affluent citizens, who proudly declared their “European” ancestry. It was a class society, just like the one of ancient Rome, where Horace and Seneca, lived within a context where slaves were abused and exploited. Many of their peers considered it to be entertaining to watch human beings being tortured to death under aesthetic pretexts, or gladiators fighting to death. Nature-loving aesthetes like Seneca and Horace were not particularly upset if a neighbour whipped one of his slaves to death and did without much scruples use their own slaves for both unpaid work and to quench their own sexual desire.

Armando Caceres's story about a god nodding in agreement has stayed with me. Once, I wrote an article about it, and even if I do not have it with me here in Rome I will try to reconstruct the course of events, with a disclaimer that some details may be incorrect.

Between high mountains and volcanoes, Lake Atitlán, which for centuries has been the centre of battles between conquerors, modern armies and Mayan descendants, who despite ruthless external influences and violence, have managed to retain much of their ancestors´ faith while adapting it to their needs.

By an inlet of the south shore of Lake Atitlán lies the small town of Santiago Atitlán, with dusty, steep streets, nowadays lined with shops selling handicraft to increasingly dense crowds of tourists and hippies. It is located with a backdrop of three impressive volcanoes - Atitlán, Touman and San Pedro. Once upon a time, Santaigo Atitlán was the center of the Tz'utujil kingdom, though in 1524 the Tz'utujiles were forced to surrender to the unscrupulous Pedro de Alvardo's Spanish troops and their allies, the Kaqchikeles, eternal enemies of the Tz'utujiles. Since then, the Tz'utujiles have been compelled to subject themselves to Christianity and serfdom.

I do not know how the state of affairs in Santiago Atitlán is today, but when I and Rose on several occasions visited the city more than twenty-five years ago, many of the traditions of the Tz'utujiles remained. Most women still had their traditional clothes; beautifully embroidered skirts and blouses, as well as their distinctive headdresses, called glorias, which consist of 2.5 centimetres wide and 10 meters long cotton bands worn like a wheel around the head, while the men wore embroidered blouses and pants of the same length as Bermuda-shorts.

What particlarily attracted me to Santiago Atitlán, which at that time could only be reached after an hour's boat trip from the town of Panajachel, on the opposite shore of the lake, was the cult of Maximon. There are several maximones in various Guatemalan Maya towns, though Santiago's Maximón is most famous of them all. There are plenty of stories about Maximon's origins. Most common is to regard him as a modern adaptation of an ancient fertility god, the cigar-smoking Ma'am, though in Santiago Atitlán I was told that sometime by the beginning of the last century it was an aj'kun, Mayan traditional priest, who at Santiago Atitlán´s cemetery found the mask of "a Judas".

It is a Spanish tradition to hang and burn a human seized doll on Good Friday, representing Judas Iscariot, the disciple who betrayed Christ. In Santiago Atitlán, this effigy was made out of straw covered with clothing and equipped with a wooden mask, this was generally cut out from tsaj'tol, a species of wood that, according to the holy scriptures of the Mayan Popul Vuh of the gods, was used to create the people after the second fall of the world. We are now living in the fourth period of humanity.

Tsaj'tol, American Coral Tree (Erythtrina Rubrinervia) is venerated by all ancient Native American cultures. Aj´kunes use its red seeds for divination. Its bark and flowers are cooked and used as medicine for various ailments. The brew has a mild hypnotic effect, which is assumed to make women aroused, in particular if tsaj'tol is cooked together with the fly amanita, from which mycelium the tree is believed to grow. The religious trance that tsaj'tol is believed to produce is probably as reason to why it is called “the talking tree”.

The aj'kun who found Maximón was none other than Francisco Sojuel. Some claim that he was killed in 1907, chopped to pieces by his enemies, but others say that Sojuel never died. During nights he has always been walking through Santiago Atitlán. Admittedly, he found Maximon's mask at the cemetery, but he himself had manufactured it thousands of years ago. In fact, Maximón is Rilaj Ma'am "The Ancient One", who created forgetfulness, hunger, sterility and madness, but he also sustains their opposites - memory, abundance, saturation, unlimited virility and knowledge. Like Francisco Sojuel, Maximon walks at night through Santiago Atitlán, and in the form of a young man he seduces beautiful women. It was to hinder Maximon´s constantly wanderings around the world, that Sojuel cut off his head and legs and then tied them together again so he could not leave Santiago Atitlán anynore. Maximón actually means "The Bundled One".

Maximon's face is oval, with a straight nose, squinting eyes and a sharp, half-open mouth through which he smokes cigars, or cigarettes. Maximon's face mask spoke to Sojuel and asked him to bring to his house. Since that day, Maximón has for a year lived in the residence of a member of his cofradía, brotherhood, until Easter, when he changes domicile

Maximón is about one metre high. He is wears the characteristic cotton trousers of the Tz'utujiles and a variety of colourful ties and shawls covering his entire body. On his head Maximón wears no less than three Stetson hats and he also has brown, well-polished leather shoes. Maximón welcomes his visitors in a room decorated with different coloured crepe festons and is always surrounded by aj'kuner, aguaciles, bodyguards and other cofradía members. Several are often drunk. They drink home-distilled brandy, not for pleasure, but because alcohol and smoke make them "risie up" to the abode of spirits and gods. Once I talked with an aj'kun who claimed that the toughest hardship connected with his calling was the excessive drinking. He called it la carga, the burden. Several times he repeated the word - la carga, la carga and sighed heavily.

Maximón helps us to get in touch with the other sphere. He is both god and man. He is a Judas, a traitor. I asked an aj´kun how it came that he showed respect and reverence to a traitor:

– Because he´s like us. All humans are traitors. Nobody is perfect, neither you, nor me. We are all liars who pretend to be better than we are. Not Maximón ... he's honest. He acknowledges that he is both villain and god. Since he´s neither a saint, nor a mortal, he knows us all and that is the reason for us turn to him in confidence. He is authentic. We can trust him because we know how he is. God also trusts Maximón, because he never pretends to be someone else.

Maximón is neither Tz'utujil nor White. He is married to a Tz'utujil lady and has a white mistress - Yamteh'or, Virginwhore. Maximón likes to take a glass or two and he smokes like a chimney, is completely without morals and constantly looking for women to be laid. He is like us, though much wiser. He knows everything and is a part of the entire world.

Once I visited Maximón together with Víctor, he was a Cuban gentleman and married to Rose´s sister. It was Víctor and Anys who received us when I first came to the Caribbean with Rose. He was the first to listen my broken Spanish and we became friends at once. Víctor was a nice man, more than thirty years older than Anys and he died a couple of years ago, grieved by those who knew him. When we arrived at Maximóns cofradía, one of the aj'kunes recognized me. Gracefully he greeted Víctor and me, but regretted that Maximón was not there to meet us. He was sleeping his siesta in the loft above us, but if we would like to do it, we could always take a look at him. Maximón always slept soundly and was not disturbed by any visitors.

I and Víctor climbed up a steep ladder, and in loft was Maximón. His feet were facing us, pointing upwards in their polished leather shoes. We could not discern his and he slept under heavy a blanket. His Stetson hats hung from the wooden wall.

– He's not breathing. He´s completely immobile, Víctor whispered.

– But, he's not alive. He's a wooden figurine, I whispered back.

Víctor looked surprised. Obviously I had forgotten not explain that Maximón was an effigy.

– But, they´re talking about him as if he´s a living person.

– Maybe they think he is, I told Víctor while we climbed down again.

And Armando Caceres? What about his story? Even before I met Armando, I had read about an incident which occurred in Santiago Atitlán 1950.

At that time, the town did not have priest of its own and that year the Easter celebrations were for the first time organized by a certain Father Godofriedo Recinos from El Salvador. When Father Recinos arrived at the church, he became violently upset by finding Maximón placed on the church´s staircase, where the god received sacrificial gifts from the townspeople. After having kicked down Maximón, the priest was almost lynched by the angry Atitecos, though a couple of "literate boys” managed to calm down the people and declare to the priest that he absolutely could not harm Rilaj Mam, because he was a powerful god and Santiago Atitlán's patron. Infuriated the priest left the square and run to the covent, where he kept his revolver. Armed, Father Recinos returned to the church staircase, where he once again kicked down Maximón, while he shouted:

– I die for the truth, but I will make sure that you follow me [in death] and come to hell as the pack of idolaters and you will be!

Because Recinos fired several shots, though they did not hit anyone and seince he kept aiming his revolver at the crowd, the aj'kuns let him leave their town unharmed. However, six weeks later, Father Recinos returned with a motorboat and in company with two other priests. Late in the night they broke into Maximon's home, they destroyed his effigy with machetes and left with two his wooden masks. One of them disappeared completely, but after a couple of years the other one appeared in the Musée de l'Homme in Paris. Armando Caceres claimed it was Nathaniel Tharn who brought it there.

For a few years in the early fifties, the anthropologist and poet Nathaniel Tharn lived in Santiago Atitlán to write a doctoral thesis on the Maximón cult. Surprisingly, Tharn wrote his studies of Mayan religion and Buddhism under the pseudonym “Michael Mendelson”. Tharn is of French, Romanian, English, Lithuanian origin and born in Paris, where he studied anthropology and for several years occasionally was attached to the Musee de l'Homme. He now lives outside of Santa Fe in the United States.

Armando Caceres is a nice, somewhat bohemian guy, well – he is older than me, who is an ethnobiologist at University of San Carlos of Guatemala and is thus familiar with all sorts of Mayan lore, personally acquainted with several aj'kuns all around Central America and Mexico. Even though he was a respected researcher, Armando was at the time I got to know him something of hippie who happliy moved around within informal circles where he had become acquainted with a certain Martin Pretchel. Pretchel's mother was a Canadian Native American and his father was Swiss palaeontologist. Prechel had grown up among Pueblo Indians in a village in New Mexico, where his mother had worked as a school teacher.

Together with Pretchel, Armando once visited Maximóns cofradía, where one of the aj'kuns unexpected approached Martin Pretchel to impress him. Nicolás Civiliu Tacaxoy, who had been present when Father Recinos destroyed Maximón, began to speak in an enthused manner, grabbed the Yankee by his shoulders while he saw straight him into the eyes:

– I had a dream that a young man who like Maximón, belongs to the two worlds, would come here and become one of us. You are the one who will bring back Maximón's face to him. You will be his telenel [carrier]. The face is somewhere far from here and you're the one who will bring it here.

Armando knew that the mask had been deposited in the Musee de l'Homme and together Pretchel he wrote a letter to Nathaniel Tharn, who promptly responded. After a year, the mask was formally brought to Santiago Atitlán by an attaché of the French embassy and ceremonially handed over to the representatives of Cofradía de Santa Cruz, which is the official name of the Maximón´s cofradià. Below we see Nicolás Civiliu Tacaxoy, Pretchel and Tharn at the ceremony which took place in 1979.

Now we finally arrive at the god's nod. Nicolás Civiliu declared to the surprised French that he could not accept the mask on Maximón's behalf, it was the god himself who had to accept it.

– How would that be possible? wondered the bewildered Frenchman. The aj'kun nodded towards Michael Pretchel:

– It´s him over there whom Maximón himself has chosen to be his telenel. It is he who will give him his face to tonight. If Maximón accepts the, we accept it as well.

During the evening, lots of candles were lit and placed on the floor in front of Maximón. The cofradía members danced their strangely tripping dances and sang their hymns, drinks were passed from man to man while they repeatedly asked the Pretchel to try to hand the mask over to Maximón, but nothing happened. Only just after midnight when the American once again had kneeled down in front of Maximón and once again hold out the mask of him, that Maximón unmistakably nodded three times. The mask had been accepted and the cofradía members laughed and cheered.

– We all saw it, Armando declared. I am fully convinced that Maximón nodded. Though, what should be said as well is that by that time we were all pretty drunk.

When at a later occasion asked an aj'kun if Maximón now was equipped with his original face, he answered:

– No, no, it's a copy, we've hidden the original.

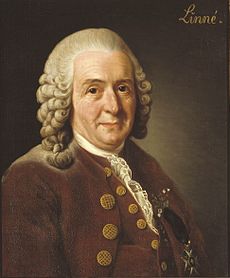

The Numina are apparently everywhere. Carl von Linnaeus (1707 – 1778), the great Swedish naturalist and sharp observer of everything around him, was firmly convinced of God's presence in his creation. Linnaeus could marvel at the unusual waste of offspring from plants and animals, which constantly withered down, were killed and slaughtered, though for Linnaeus all of this was part of the infinite chain of power and life of existence. All living things are dependent on other organisms and God is behind everything turning a constantly evolving cycle.

God Almighty is also present and active in the lives of every human being, he is also an essential part of human morality. In his strange book Nemesis Divina, Linnaeus kept a record of how God punished his enemies. To Linnaeus human ethics equalled the natural laws – God chastises those who violate his rules.

On the door frame to the bedroom on his farm in Hammarby, Linnaeus had set placed a picture of a whale and her calf. Underneath the picture he had written Innocue vivito, numen adest, Live righteously – a Numen is present.

I honestly do not know if I am religious or not. I actually think I am. Otherwise, I would not have experienced so many absurdities. It seem that a higher, benevolent power is watching over me, in spite of the indescribable misery that befalls so many of my fellow beings, many of whom are more deserving, much nicer and better than me. It is there, like in the words of the Beatles´ song:

Do you believe in love at first sight?

I'm certain it happens all the time.

What do you see when you turn out the light?

I can't tell you but it sure feels like mine.

Blunt, Wilfred (2001) Linnaeus: The Compleat Naturalist. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. Euripides (2005) The Bacchae and Other Plays translated by John Davie. London: Penguin Classics. Ferguson, John (1985) The Religions of the Roman Empire. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press. Guillén, Jorge (2013) Cántico. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva. Horace (1967) The Odes of Horace, translated by James Michie. Aylesbury Bucks: Penguin Classics. Kozljanič, Robert Josef (2011) “Genius loci and the numen of a place: A mytho-phenomenological approach to the archaic,” in Bishop, Paul (ed.) The Archaic: The Past in the Present. Hove: Routledge. Mendelson, Michael E. (1965) Los Escándalos de Maximón. Guatemala: Minsterio de Educación. Otto, Rudolf (1958) The Idea of the Holy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rätsch, Christian (2005)The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and Its Applications. New York: Park Street Press. Seneca (1969) Letters from a Stoic: Epistulae Morales ad Luclium. London: Penguin Classics.