RUSSIAN FOLK LEGENDS: Koščéj and Putin

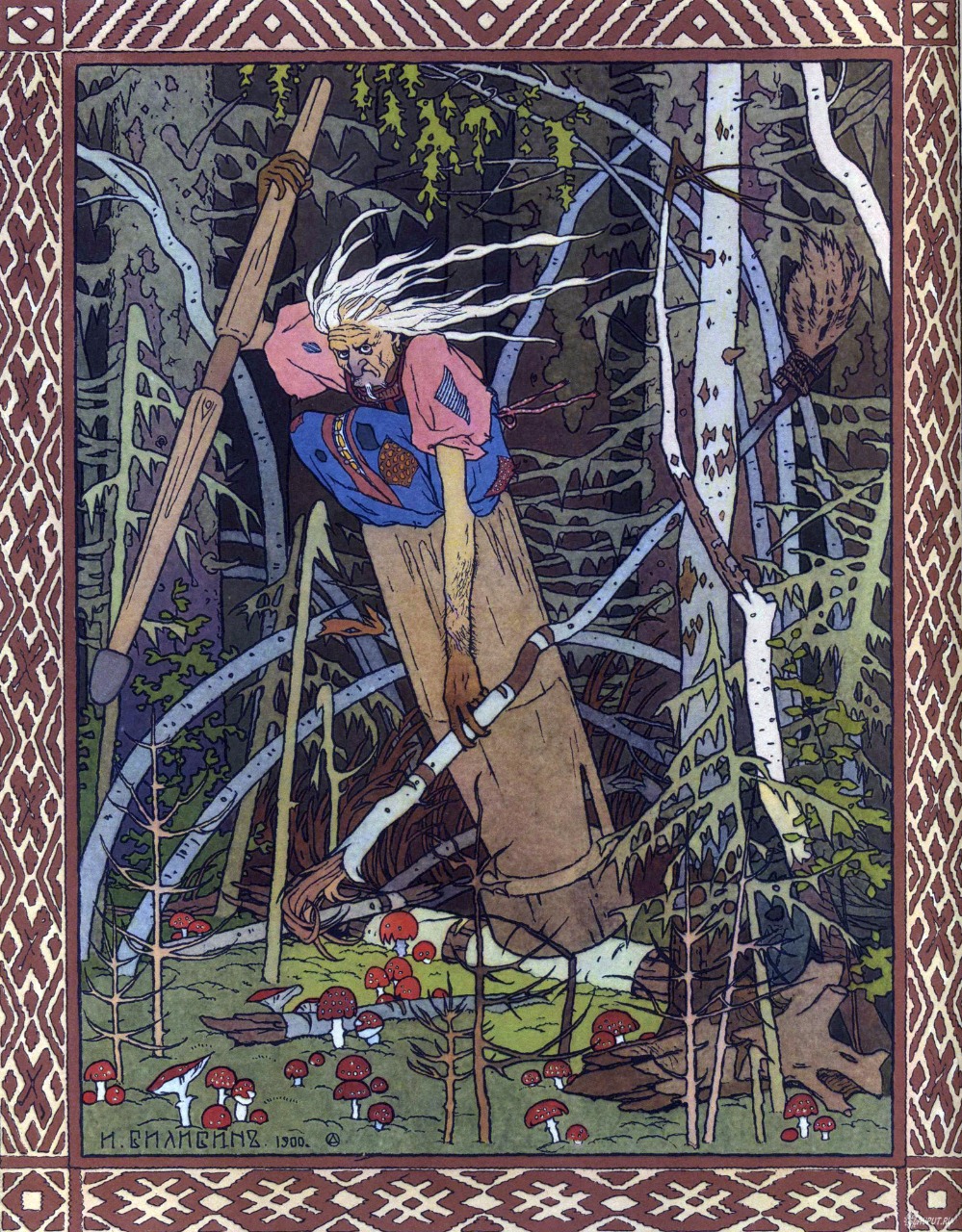

Since ancient times, lies the cottage of mighty witch Baba Yaga close to the heart of Russia's vast forests. For sure it is no gingerbread house, built to attract hungry children lost in the woods, although its owner more often than not has a ravenous hunger for human flesh, in particular succulent meat of well-nourished kids. On the contrary, the fearsome appearance and behavior of the lodge, it has a will of its own, appear to fence off people rather than attract them. The surrounding palisade is made of human bones and the fence poles are adorned with skulls, from whose eye sockets a frosty glow spreads in the dark of winter nights. One sharpened pole is empty, in anticipation of being adorned by an unfortunate visitor's skull. The witch attaches it to her fence after she has feasted on the roasted body of her innocent victim and gnawed its skull clean from flesh.

It may happen that a daring youth, or a banished maiden, voluntarily seek out this eerie abode. The old woman who lives there is brooding on a great wealth and she is the ruler over all forest beings. Predators and birds are governed by her, as well wayward cattle and coveted wild horses. It has been said that Baba Yaga is the first mother of all mankind, that she is identical to Mother Earth. That she can transform herself into a cloud, that even the sun and the moon are governed by her, as well as draught and tempests. Her abode stands close to the gates of Hell; maybe she is Death. In any case, demons and dragons obey her.

As mentioned above, her house appears to have a life of its own. It rests on strong chicken legs and from whatever direction you chose to approach it, the cottage turns its front towards you. If you want to enter you have to restrain the lively house by commanding: "Little house, little cottage, set your face towards me and your butt against the forest", then the house bends forward like a chicken picking up a grain and the front door opens. The brave adventurer who enters the untidy kitchen does not at first discern the old crone who dwells in there. Either she is curled up like a cat on the slab above her huge oven, or she has extended her gawky body along one of the hut´s walls. The visitor may mistake her for a log, gnarled and craggy as she is. However, the vistor will sooner or later hear the witch's scratchy, dry voice when she angrily sputters something about russkim dukhom "stench of a Russian". Like all other beings from the regions of Hell, Baba Yaga knows the difference between a ghost and a living soul. With her pointed nose she sniffs up into the stale air, lifts her head, looks around until she drills the sharp stare of her luminous red, eyes deep into her visitor.

In her authentic appearance Baba Yaga is definitely not a beautiful being, though she sometimes transforms herself into an alluring middle-aged woman. Generally, when she has to make one of her rare metropolitan visits.

At home she prefers her sunken cheeks, sparse stubble and sickly yellow skin that tightly covers her skull. Greasy, gray tufts of hair frame her high forehead and dirty face, bared wild boar tusks protrude from the corners of her shrunken lips.

A peculiarity Baba Yaga shares with many other fairytale villains is a visible and incurable injury. Baba Yaga is lacking a leg, it is replaced by an artificial one, either of wood, or clay. The witch in the fairytale of Hansel and Gretel also has difficulty in walking and is leaning on a cane. Perhaps this suggests that even mighty monsters may be wounded and defeated, or it may also mean that mental deformities are reflected by their appearance; that their wickedness is related to an inner dichotomy - the damage seems to affect body parts that generally occur in pairs; like an eye, a leg, or an arm.

Many believe that there are more than one Baba Yaga, she appears at different locations at the same time and it is said that she has several sisters and daughters, remarkable women who are believed to propagate themselves, no men seem to have been involved in their creation. Others believe that the various Baba Yagas only are different aspects of the same Baba Yaga, like Virgin Mary who appears in different guises, with diverse messages at various locations. Maybe does Baba Yaga out of her own force, like the dark, fertile soil, produce plants and animals, as well as she fertilizes and protects them? In addition to her spindly and damaged legs, which imply her connection with death and torments, she has huge, milk distended breasts.

Baba Yaga is possibly not bad to the bone, not entirely evil, rather injured or poisoned by too much power. It happens that the witch reluctantly develops a liking to a visitor and declines to slay him/her and instead puts the reckless visitor to difficult tests only to ascertain that s/he may be worthy of her trust. If the old hag is outwitted she accepts defeat and may become both generous and protective. However, if she is not in a good mood at the first encounter with a stranger, but rather hungry and ferocious, Baba Yaga hurls herself over the wretched caller who climbs over her doorstep, rips her victim´s throat and turns the corpse into a tasty dish. Her house is mined territory - each thought, every step must be carefully calculated. You must be respectful and let the witch speak before you say something. Powerful creatures hate to be contradicted, taught and admonished. Reply if asked, but watch your words, witches are able to sniff out a mistake and hurl themselves on it as if they were starving wolves.

You cannot escape Baba Yaga. If you rush out the door she throws herself in a flash on top of her huge wooden mortar, using it to pursue her intended victim, rushing forward like a blizzard, punting with the pestle, while she uses a broom to sweep away her tracks. Finally, the pursued cannot keep up the speed, staggers and falls to the ground. The witch leans over her prey and opens up her huge mouth, which can be extended from earth to heaven. It is Hell that opens up to devour the hapless loser, obliterating all traces of her/him.

Baba Yaga has many servants, vilest is Koščéj the Deathless. He may be Baba Yaga´s male aspect, though Koščéj appears to have a life of his own, even if he must obey the mighty Baba Yaga and appear when she calls for him. Koščéj is a powerful Tsar, with a vast kingdom of his own and an almost invincible army. It might be Hell he rules over, the name Koščéj sounds much like the old Slavic name for the place - Koshchnoye.

Like Greek Hades, Koščéj has a weak spot for beautiful ladies and he has throughout the years abducted quite a few lovely maidens from their husbands and relatives. He tries hard to seduce them; oddly enough it happens that the old debauchee succeeds in his intent, something that may seem strange considering the fact that he looks, to put it mildly, hideous. Koščéj does not die, but he is aging. In a few folk tales a fair maiden might choose to abandon her lover for the sake of the wealth, security and power he offers her.

Far back in time Koščéj found a method to separate his body from his soul, since none of them will die if they live separately. At that time, Koščéj was a handsome warrior who wanted to hide his soul in order to remain undefeated in every battle.

The price was high. He now looks like a cadaver. It is feasible that Koščéj through some magical tricks is able to hide his true appearance, or pervert the perception of his female victims. Through his powers and wealth he flatters and pampers his victims and if an abducted lady assures him that he is admired, or even loved by her, he believes the lie. Legends may offer scenes where a captured maiden allows the old monster to rest his head in her lap while she quietly asks questions to him, untangling his matted hair, delivering it from lice. Then Koščéj becomes dazzled by his own excellence, something which is the weak spot that eventually causes his annihilation.

Koščéjs body can only be damaged by age and killed if someone finds his soul - his vulnerable humanity - and crushes it. It is by denying and hiding what his fragility - love and compassion - that Koščéj did manage to transform himself into a powerful and invulnerable being. He has taken the soul out of the body. However, that does not impede a constant search for love, a feeling that nevertheless is unavailable for a soulless man. By abducting young women he may occasionally dampen his sexual urge, though just for a moment. He he can neither give nor receive love, possibly admiration, but such an emotion will be based on fear, mixed with submissiveness. As a powerful man Koščéj does not hesitate to exploit his captives, among other things, he force them to weave him armies and feed the evil demons that serve him in the form of docile doves, though if threatened they turn into hideous creatures like himself.

Maybe due to his advanced age Koščéj feels that he constantly has to prove his vigor and does for example every morning ride out for an exhaustive hunt in his forests. His steeds are wild and famous, some of them have three or seven legs and they can all speak, if they stumble it is a sign of upcoming danger. Koščéj is a bon vivant constantly on the look-out for exclusive conveniences, among other things, he has a fur-lined cloak, which is warm in winter and cool in summer. Though his advanced age sometimes takes its toll and he is often so tired that a servant is forced to stand behind his throne and occasionally lift up his heavy eyelids. It happens that Koščéj´s melancholy engulfs his entire court; the demons and people surrounding him then run the risk of being turned into stone and can only be awakened by the sound of a gusli, a kind of zither. In all his authoritarianism Koščéj is a lonely, insecure and thus dangerous beast.

If anyone would find Koščéj´s soul and unravel him in all his human nakedness and vulnerability, he instantly loses all his powers. Therefore, he has made his soul utterly inaccessible. He has impaled it on the top of a needle placed inside an egg within, which lives in a hare, encased in an iron coffin, over which a mighty oak has grown up. Koščéj´s immortality has made the oak old and strong and it encloses the coffin with its tenacious roots. The mighty tree can be found in the middle of a forest on an island far out on a desolate ocean.

Like any kind of power, Koščéj´s strength is maintained through confirmation. The old demon has committed all imaginable sins and crimes, but what will be his final error is to succumb to his vanity. As the Devil himself has noted: "My favorite sin, through vanity I can manipulate anyone." Koščéj´s most dangerous opponents are thus those women who are able to flatter his vanity, like the beautiful and intelligent Vasilsa Kirbitevna, who when Koščéj came back from his daily hunt:

threw her arms around his neck, caressed and kissed him, all the while whispering to him. "You are my dear friend, I could hardly wait for you to come. I even thought you might not be among the living. I thought some fierce wild beasts had devoured you!” Koshchei laughed: “Oh, you silly woman! Your hair is long, but you are short of wit. Could fierce wild beasts really eat me?” “And where is your death?" "My death is in that besom, it hangs out next to the threshold.” Just as soon as Koschei had flown away, Vasilisa Kirbitevna ran to Ivan Tsarevich and Bulat the Brave asked her. “Well, where is Koshchei´s death?” “In the besom that´s next to the threshold.” “No, he´s intentionally lying. We´ll have to be cleverer to get the truth out of him.” Vasilisa Kirbitevna immediately thought something up: She took the besom and gilded it, and tied various ribbons on it and put it on the table. When Koshchei the Deathless flew in, he saw the gilded besom on the table and asked why it had been done.

Vasilisa replied that she thought it was not appropriate that Koščéj´s death was so carelessly treated. Koščéj became flattered, but nevertheless told her another lie: "Stupid woman, my soul is not there. It is hidden in the goat." Vasilisa coated the goat´s horns with gold paint and adorned the animal with colored ribbons and bells. When he saw it Koščéj thought that the cunning girl was serious about her admiration and finally told her about his soul's hideout. That revelation became Koščéj´s undoing.

Stories about Koščéj are an integrated part of Russian lore. The hero of these tales are always called Ivan, while the name of the strong and cunning maiden varies, her most common apparition is as an exquisitely beautiful warrior woman called Marja Morevna, often appearing in folk tales presented by Afanasiev, who is considered to be Russia's equivalent to the German Brothers Grimm.

Aleksandr Nikolaevich Afanasiev (1826 - 1871) was Russia's greatest collector and publisher of folktales. Many believe that he was far more diligent and better than the Brothers Grimm, in the sense that he wrote down the tales as they were told among peasants, his changes were very cautious. Afanasiev worked as a librarian at the Imperial Archives in Moscow and it was through this profession he came in contact with folk tales and those who collected them. His interest became an obsession. Afanasiev published a collection of more than 600 Russian folktales and then proceeded to write an analysis of them, Slavs´ Poetic View of Nature, published in three volumes, each one with more than 700 pages.

It was Afanasiev´s pursuit of perfection that became his downfall. In his careful editions of folktales, of which the best and most accurate had been collected by his friend, the linguist Vladimir Dal, who wrote them down as phonetically accurate as possible, Afanasiev did not hesitate to publish stories that irritated Russia´s rulers and in particular the powerful authorities of the Russian Orthodox Church. What aroused the greatest offense to the clergy were Russian peasants´ candid tales about rural sex life. When the powerful Philaret, Vasily Mikhaylovich Drozdov, Metropolitan of the Moscow Patriarchate and one-time friend of Pushkin attacked Afanasiev for his publications of obscene stories, the librarian answered him back in a newspaper article and thus brought upon himself the unbridled hatred of the Church. Afanasiev wrote:

There is a million times more morality, truth, and human love in my folk legends than in the sanctimonious sermons delivered by Your Holiness.

.jpg)

After that incident Vladimir Dal had given Afanasiev a large amount of erotically uninhibited stories and told him: "I have in my collection many such stories that cannot be printed - it is a pity since they are so entertaining." Afanasiev, however, could not refrain from editing the salacious stories and gave a copy to his good friend, the renowned freethinker and exiled Russian Alexander Herzen, while visiting him in London. Naturally, the dreaded Russian Ohkranan, "Division of Patronage of Public Safety and Order", found out where and when that visit had taken place and after Afanasiev´s return from his trip abroad the Tsar's secret police showed up and turned his apartment upside down until they found a manuscript of Russkie zavetnye shazki, "Russian secret folk tales". Afanasiev was immediately removed from his post, blacklisted and unable to find a new employment. The degraded librarian sold his own extensive library to get money for food for himself and his family. He lived out his last days like a wretch out of a history by Gogol or Dostoevsky, got tuberculosis and died destitute, only forty-five years old. Ivan Turgenev wrote to an author friend:

Afanasiev died recently, from hunger, but his literary merits will, my dear friend, will be remembered long after both yours and mine are covered by the dark of oblivion.

It is often pointed out that women play a passive role in folktales; they are waiting to be married to a handsome prince or being rescued from nasty captors, at best, they help their liberator by giving him information about their abductor´s weaknesses. If women are smart or powerful they are generally granted a supporting role as wicked stepmothers or fairy good mothers. When I read folk legends, I am often tempted to consider such perceptions as a kind of gender stereotype as well. Admittedly, there are quite a lot of tales reflecting the deplorable views of antiquated patriarchal societies, where women have been considered as simple minded commodities who have to be protected, if not – they are abducted or turn out to be independent, nasty and seemingly powerful witches like Baba Yaga. Nevertheless, I imagine myself to have found an equally large number of evil men and ruthless tyrants, along with quite a number of tough and dynamic women, not the least in The Arabian Nights and Russian folk tales.

Take for example the Tsarevna Marja Morevna in one of Afanasiev´s most popular tales, the Tsarevitj Ivan rides out to find out what became of his three beloved sisters who had been married to princes, all of whom can transform themselves into birds. On his way to the sisters Ivan comes upon a field littered with corpses and remains of a mighty army. "Is anyone alive here?" he shouts, "Let him tell me who defeated this great army!" One of the fatally wounded survivors lifts his upper body and responds: "This mighty army was defeated by the beautiful Queen Marja Morevna." Ivan rides on and arrives at the Queen's army accommodations and is there presented to the exquisitely beautiful tsarevna, who asks him: "What makes you come to me? Do you travel by demand or free will?" Whereupon Ivan replies: "A free-born nobleman cannot be coerced." Intense liking arise between the them and they are soon married.

Ivan does not bring the independent and powerful queen to his own kingdom, but do instead move in with her in her vast castle and when she is forced to embark on a new war expedition he leaves "her kingdom and everything therein in her husband's care." When she hands over the keys to all of the castle´s chambers, she also presents him with a golden one that opens the door to a place he may not enter. Of course Ivan hurries to open that door as soon as his wife has left him alone and in the secret chamber he finds Koščéj the Deathless, an emaciated old man solidly forged to the wall with twelve chains. The old demon complains: "For ten years I have been plagued here, without food and drink - my throat is parched." Ivan cannot understand how his wife could have been so cruel and carries water to the old wretch, who devours no less than three buckets and then blasts his chains with the words: "Thank you, Ivan-tsareveitj, now you'll never see Marja Morevna!" Like a whirlwind the demon hurls himself out of the window, looks up Marja Morevna in the midst of a battlefield and abducts her to his castle. Curiously enough Koščéj does not seek revenge on his former enemy but believes her when she flatters him and he imagines that she has really surrendered to his power and charm.

Unlike other tales about the immortal demon, Ivan does not try to find Koščéj´s soul but instead enters into the service of Baba Yaga. With the help of his friends, the brothers-in-law who can turn themselves into birds and a couple of animals he had shown mercy, Ivan succeeds in taming the witch's wild horses and steals her best stallion, which is even faster than Koščéj´s magic steed. Ivan's miracle horse kicks and tramples Koščéj to death, which is an exception since the monster can usually only be killed if his soul is captured and destroyed, or if he is burned to ashes. The story has a happy ending, Ivan and Marja Morevna return to their kingdom "where they lived in the best of ways, maybe they are still drinking the sweet mead".

The ending of another version of the story is more frightening. Koščéj has defeated Ivan and bound him tightly to hand and foot. In an attempt to spare her husband Marja Morevna lies to Koščéj, convincing the cruel demon that she has come to admire him, yes, even love him. Koščéj brings her with him to a tent, but barely have they entered when Koščéj through the canvas hears how an eagle, which in fact is one of Ivan's brothers-in-law, cries out that Marja does not love Koščéj. Furiously Koščéj rushes out and shoots an arrow at the eagle, but the arrow flips in the air, returns to the archer and pierces Koščéjs heart. To ensure that the monster will not to be resurrected Ivan and Marja burns its corpse to ashes. But ... as a revenge for what he has misunderstood as a betrayal, when Marja Morevna in fact only wanted to save his life, the jealous and furious Ivan cuts his wife to pieces.

The Tales of Koščéj the Immortal are generally more terrifying and remarkable than most other Russian fairy tales. Psychoanalysts have stressed that Koščéj emerges as a kind of alter ego of the "evil father". The eggs that appear in connection with Koščéj could possibly symbolize testicles and when they are crushed they destroy Koščéjs power. Either the hero finds the egg containing the demon's soul and destroys it, generally by stepping on it, or he takes it with him and finally crushes it against Koščéjs forehead, a sure way to annihilate the demon. No matter who he is - Baba Yagas alter ego, brother or servant, Lord of the Hell or a perverted father figure - Koščéj is always associated with seduction, lies, infidelity, secrecy and betrayal. A powerful man, who hides the truth about his true nature, in order to gain personal benefits.

The Russian literary scholar Vladimir Jakolevič Propp (1895 - 1970) who did make a detailed analysis of Afanasievs folktales wrote that fairytale figures should primarily be classified by their deeds and not by their name or appearance. Koščéj may exist under several other names and as a force of nature; a dragon, a devil, a falcon, a vampire or a tsar, but in any of these guises he abducts women, appears as an evil rival to the hero and lacks a soul. Popp equates Koščéj with Death, who in many cultures is personified as a living skeleton abducting people. Propp consistently calls Koščéj The Skeleton. It is clear, however, that in all his guises Koščéj abducts women, emerges as a sinister rival to the hero and lacks a soul.

To abduct relatives is one of Koščéjs activities that occur in each of the stories that introduces him. This has led reserachers who have been searching for the demon's origin to discern similarities between him and the Tsar's role in Russian peasant culture, namely that the Russian ruler selects peasant boys for military service, moves peasants around in their capacity as serfs, or simply deport entire populations, all actions that may be interpreted as abductions. Tsars often occur in folk tales, but what sorts out Koščéj from the rest are his chilly appearance and inhumanity, as well as the fact that his kingdom is separated from people's everyday world.

Several anthropologists have argued that Russian peasants often seemed to share a perception that the Tsar, like God, is far away from them, in another sphere, but that he nevertheless had unlimited power over them. Olga Semyonova, who spent four years by the turn of the last century to a detailed ethnographic study of the peasants living around her family's estate, wrote that several of them felt that "The Tsar is far away from us, by the other end of the Earth." According to Semyonova was the "peasants´ God" a tangible entity that gave rain, drought, health and diseases, while the Tsar defended home and nation, and thereby had the ultimate responsibility for the peasants' well-being, but he was as distant and almighty as God.

Among the mass of peasant, there is nothing mystical about their relationship to the tsar and God, just as there is nothing mystical about their idea of an afterlife, just as they give no thought to the coming year. It is amazing how essentially irreligious they are. Everything is equally evident.

Semyonova assumes that the Tsar's power by most of the peasants is considered to be as eternal, immortal and incomprehensible as God's presence. Hunger and famine strike in the same inexorable manner as war and taxation. If God or the Tsar had a soul or not was an irrelevant question, they were entities far above such notions and were thus linked more to fate than to "humanity"

Several researchers have in Russian folk tales discerned traces of Ivan the Terrible's surviving influence over Russia and have in Koščéj´s character found hints of the legendary Tsar's cruelty, capriciousness and authoritarianism.

Like Koščéj had his demon hordes Ivan the Terrible (1530 - 1584) had his ruthless private army, the so-called opritjniki, who had exclusive social and economic privileges and were loyal only to the Tsar. Ivan used their terror to intimidate those boyars, nobles, he considered to be unreliable. Sickly suspicious of any possible usurper Ivan made his opritjniki torture and murder boyars, as well as bishops, monks and peasants. Opritjniki had unlimited powers over the peasants who lived within the districts they had been granted as rewards for their loyalty and as a source of income. Peasants were killed and bled recklessly, several fled with their families into the forests and agricultural production fell.

Plague worsened the famine, in one year more than 10 000 died only in the wealthy town of Novogrod, where the burghers in their despair turned to Tsar Ivan begging him to at least ease the opritjnikis´ terror. Instead of listening Ivan considered the appeals to be signs of a planned rebellion and ordered his opritjniki to loot and burn the city and its surrounding villages. The mayhem culminated in mass executions outside the walls of the devastated city, where Ivan witnessed the agonizing torture of thousands of victims. The Tsar himself took great pains in finding variations of torture and executions, personally killing several of the accused.

Ivan assaulted a pregnant daughter-in-law, thus causing her miscarriage, and killed one of his sons, waged war against all the neighboring countries, spread terror around him and finally abolished its oprjitnina system in fear that his sworn men would turn against him.

Ivan IV's sadism and total ruthlessness amazed even his unusually thick-skinned contemporaries. It would not be surprising if many of them came to imagine him as a kind of Koščéj, a demonic figure lacking both a soul and ordinary human traits:

He was physically and spiritually one with his realm [...]. He brought together the human and the divine, which authorized him to act to purify the world of sin, using divine violence. He was an incarnation of this union, which gave moral authority for everything he did and placed him on a par with God. It was this self-identification of Ivan with the idea of sacred violence which opened the way for the Tsar´s belief in the purificatory value of his cruelty, and enabled him to accept as divine the sadism which made life a hell for his subjects. [...] It was also the quality of Ivan´s firm conviction in his God-given duty of rewarding and punishing his people that induced in them the acceptance of the duty of obedience to the divinely powerful Tsar, to whose judgment they submitted as though it was the Last Judgment.

While reading about Ivan the Terrible Iosif Vissarionvitj Djugasvili turns up in the mind, the man who in 1913 became Joseph Stalin, Man of Steel, and when he came into power let his senseless terror plague 180 million Soviet citizens. The shadows of these demonic rulers continue to be present in Russia. The film director Pavel Lungin, who in 1990 won the prize as best director in Cannes, later became a firm supporter of Putin. Last year, Lungin signed a letter in support of Putin's military operations in Crimea and the Ukraine. In 2007, Pavel Lungin introduced his film The Tsar, about Ivan the Terrible, with the words:

Some believe that the spirit of Ivan the Terrible is disappeaing further and further away from us, while others dream of a contemporary equivalent to this force that once again will gather everything that has fallen apart and been destroyed by years of reform. Because, as many historians can confirm, it was under Ivan IV that the Principality of Moscow was converted into the Muscovite state, our Nation's predecessor. This is the Russian state secret. All dictators, each one of those who in some way have been connected to the violence that repeatedly has unleashed oceans of blood over our people has been linked to this strange masochist love of a violent past.

Similar reasoning may to some extent be linked to Vladimir Putin, who on numerous occasions has expressed his desire for having today's textbooks rewritten in such a way that they "create a sense of pride in our history, in our nation." This nationalistic vision has meant that both Stalin and Ivan IV are beginning to be revalued in a more positive light.

One such example has been the release in 2007 of Alexander V. Filippov's The Contemporary History of Russia, 1945–2006, intended as a high school book in modern history. It was accompanied by a teachers' manual that among other things stated that “it is important to show that Stalin acted in a concrete historical situation…entirely rationally - as the guardian of a system, as a consistent supporter of reshaping the country into an industrialized state."

In The Contemporary History of Russia Stalin's is considered in relation to Ivan IVs establishment of the Muscovite state that initiated “a 500-year political tradition which demanded that power be concentrated in the hands of a single, autocratic ruler and his centralized administrative system.” Filippov stated that Stalin prioritized the national defense, as well as an economic modernization process supported by a strict administrative command structure. Even Stalin´s most cruel means were in the end justified by their ends – a reunification of the former Russian empire and its transformation into an industrial superpower, after winning a war of epic proportions. While accomplishing this policy Stalin considered himself to be the heir of strongmen like Ivan IV and Peter the Great. He was a connoisseur of Russian history and deemed such leaders to be his mentors.

The latter is apparently true. A Russian historian, Robert Yurevich Vipper (1859 - 1954), wrote in 1920 a book about Ivan the Terrible in which he compared the ongoing Bolshevik revolution with the "military-autocratic communism" which according to Vipper had characterized Ivan IV's regime. Vipper was at that time not a Bolshevik, he left Moscow for the University of in Riga to avoid Communist fanaticism. Nevertheless, Vipper understood that Lithuania sooner or later would succumb to the Soviet power and during the thirties reassessed his views of the Bolsheviks and deemed their state dictatorship as a worthy successor of Ivan the Terrible's endeavors. Vipper chose to ignore Ivan IV's senseless terror and regarded him more as a dedicated nation builder. Soviet leaders ought to demonstrate similar strength and ruthlessness, thereby establishing Russia's power and glory. When Lithuania was annexed in 1940 Vipper became member of the USSR Academy of Sciences and a leading historian whose research supported Stalin's quest to restore Ivan the Terrible as a role model; an able and admirable leader. During a highly acclaimed lecture in the Kremlin, which the radio broadcasted throughout the Soviet Union, Vipper proclaimed that: "Ivan's Muscovite state was the prototype of the USSR's multi-national state."

In this context it may be noted that the epithet "Terrible" in Russian is Grozny, a concept that can be translated as “fearsome", "awesome" or "redoubtable". Afanasiev´s friend, the linguist Vladimir Dal, identified the word as an archaic epithet of powerful leaders and that it back then had the meaning of "brave, magnificent, superb, keeping enemies in fear, but subjects in obedience."

Stalin thus did not mind at all being compared to a sadistic tyrant like Ivan the Terrible, but he did not want be connected with his mythical doppelganger, the abominable Koščéj. It is possible to connect Osip Mandelstam's poem about the Kremlin Mountaineer with myths surrounding fearsome creatures like Koščéj the Immortal, the demon without a soul who reigns over a realm of death filled with smirking sycophants, who suddenly may be ossified by the demon's remarks or bad moods.

Mandelstam was in November 1933 reading his poem to a select group. Those who listened were his poet friends Boris Pasternak, Anna Ahkmatova and Sergei Petrovich, as well as Osip´s wife Nahdezha and, according to Robert Littell in his documentary novel The Stalin Epigram, a certain Zanaida Zaitseva-Antonova, who had been Mandelstam's mistress. According to Littell it was Zanaida who wrote down the poem and brought it to OGPU, the secret police that next year would become the dreaded NKVD. The poem became Mandelstam´s death sentence:

Our lives no longer feel the ground under them.

At ten paces you can´t hear our words.

But whenever there´s a snatch of talk

it turns to the to the Kremlin mountaineer.

the ten thick worms his fingers,

his words like measures of weight,

the huge laughing cockroaches on his top lip,

the glitter of his boot-rims

Ringed with a scum of chicken-necked bosses

He toys with the tributes of half-men

One whistles, another meows, a third snivels.

He pokes out his finger and he alone goes boom.

He forges decrees in a line like horseshoes,

One for the groin, one the forehead, temple, eye.

He rolls the executions on his tongues like berries.

He wishes he could hug them like big friends from home.

Putin does not deny Stalin's terror, though the question remains whether he has a clear idea of what it really meant for the individual Soviet citizen who was severerly affected by it and how it has deeply hurt the Russian nation and its neighboring countries. If he has such an understanding, it is somewhat difficult to understand why he has compared the terrible Stalinist right abuses with other types of crimes, committed by other nations. During the conference that introduced the aforementioned textbook in modern Russian history, Putin said, among other things, in a TV broadcasted speech:

Yes, we had terrible pages in Russia’s history. Let us recall the events since 1937 [the year of Stalin´s "Great Purge"], let us not forget that. But in other countries, it has been said, it was more terrible. No one must be allowed to impose the feeling of guilt on us. Let them think about themselves. But we must not and will not forget about the grim chapters in our history. Though we have not used nuclear weapons against a civilian population. We have not sprayed thousands of kilometres with chemicals, [or] dropped on a small country seven times more bombs than in all the Great Patriotic War.

When I read the Russian journalist Masha Gessen´s disturbing book about Putin's rise to power, The Man Without a Face, I was once again reminded of how the stigma of absolute and ruthless authorities rests heavily upon Russia. In her book Gessen describes, with astounding bravery, how a violent troublemaker and mediocre student from humble beginnings in Leningrad´s half misery through various rackets moved upwards within the ranks of a KGB threatened by democratic reforms and then through contacts with powerful oligarchs, many of whom later became his sworn enemies, ended up among the political leadership of a Russia that increasingly became more corrupt and controlled. How Putin early on realized the potential of media as a means to achieve and maintain power by building up the image of an incorruptible superman able to set everything right. He is accused of having come to power through KGB machinations, which among other things included staging acts of make-believe terrorism that could be blamed on Chechen zealots and thereby support Putin's campaign to extend the dirty war in the Autonomous Chechen Republic and thereby strengthen Putin´s power by associating him with the protection of Russia from terrorism.

Compared to the mentally unstable sadist Ivan IV, who slew a fair amount of his subjects, but "founded the Russian political structure" and the paranoid, psychopath Stalin, who caused death and terror to a degree Ivan the Terrible could not even have dreamt of, but who by some hardcore fans still are venerated as the powerful leader who initiated and headed an era of "unity, strength and national honor," Putin has not wandered off into madness and indiscriminate terror methods, but like his authoritative predecessors Putin is most willing to be hailed by the masses and being considered as the strong leader who brought order to the economy and social system.

Putin seems to have been inspired by the personality cult that developed around Stalin. Recently I watched an episode on Swedish TV of a program called All are photographers, where one of the participants was assigned to make official photographs of bridal couples. His colleague pointed out that a task like that reminded him of the plethora of perfunctory and dreary portrait studies of politicians, who generally were depicted in insipid poses in pulpits, or sitting stiffly posed among colleagues and/or family members. It's completely different in the case Putin, where images taken of him are far more interesting, caught with speed and gusto from intriguing angles allowing Putin to come out as a incessantly active macho who moves around within intriguing settings. Being Putin's official photographer must be much more exciting than stumbling around in the shadow of European politicians.

Gessen and other investigative journalists are moderately amused by such displays, warning about the danger in underestimating the dangerous potential of Putin's character and the endeavor his entourage has embarked on. According to Gessen, Putin´s agenda revolves around tense control of the media, silencing and even murdering vociferous critics, coarse lies and manipulations, and above all inhibited theft committed by a closed circle of old buddies. It is the story of a mafia group whose members through policy, serious crime and economic manipulations have seized control of an entire country and finding themselves in the middle of a process of embezzling anything they can lay their hands on. Putin's KGBpals have ended up as directors of state companies. They are the new oligarchs. After having served the state the secret police is now taking over it, which means that the Organization´s traditional enemies - rights activists, journalists and lawyers - now live dangerously.

Gessen´s book also involves a search for the personality, or why not the soul, of an apparently ruthless careerist who, like Koščéj in Russian folk legends oozes coolness and inaccessibility. A tiny, easily upset and gray man has been turned into a big game hunter and martial arts master. A strong and tough, but deep down OKguy who has everything that is required for controlling a complex empire. An image that is not soiled by vulgar language, as when Putin after the apartment building explosions shortly after his accession to power blamed them on Chechen terrorists, the new Russia´s permanent scapegoats and declared: "We'll follow the terrorists everywhere. We'll blast them out, even in the shit-house. End of story."

To me Putin's true nature remains a mystery. He may be a great statesman, though I unfortunately lean towards a perception that he may be more of a Godfather, a capo di tutti capi that makes me think of Koščéj, the Immortal, the mysterious macho man who hid his soul, but was hunted down and defeated by bold women like Marja Morevna and Vasilisa Kirbitevna. In Putin's case, such women may be equivalent with brave journalists like Masha Gessen, or Anna Politkovskaya, who paid with her life for her disclosures, and Karen Dawisha who in her book Putin's Kleptocracy describes gangster economics promoted by former KGB agent and his collborators.

Putin is the head of state who can disappear for weeks without his subjects knowing where he is. He is a man who rightly says: "I have a personal life in which I do not allow any interference. It must be respected." Putin's good friend Silvio Berlusconi repeatedly makes the same statement, he is like Putin a media controller and a millionaire. Unlike Berlusconi Putin denies that he is a millionaire, according to him, it is a lie spread by his political opponents and nothing more than "bullshit as usual". Despite their opinions about "privacy", neither Putin nor Berlusconi hesitate to give orders to unscrupulous journalists to rummage in the privacy of others and spread scandalous rumors about individuals they regard as being their enemies.

Moreover, I cannot help but wonder about these admired men's personal life, especially after reading the transcripts of Berlusconi phone conversations with the high-end prostitute Patrizia D'Addario: "I'm going to take a shower too. If you finish before me, wait for me on the big bed," the then Italian Prime Minister can be heard saying. "Which bed? Putin's?" queries his companion. Berlusconi answers: “Putin´s”, Patrizia giggles: “Oh, how cute! The one with the curtains.” The exact meaning of this conversation is somewhat unclear, but still reminds me of the aged Koščéj´s escapades, or why not how despicable, powerful old men abuse young women, like Dominique Strauss-Kahn, or our Swedish representatives of this distasteful kind of power drunk personalities, like the former Rector of the Swedish Police Academy.

But it is mainly the common talk about Putin's soul that made me think of Koščéj. It all started when Bush met Putin for the first time in 2001, and the American president declared:

I looked the man in the eye. I found him to be very straight forward and trustworthy and we had a very good dialogue. I was able to get a sense of his soul. He's a man deeply committed to his country and the best interests of his country and I appreciate very much the frank dialogue and that's the beginning of a very constructive relationship.

Apparently Putin seized Bush's romantic, Christian soul by showing him a cross he had received from his mother before an official visit to Israel. "She asked me to get it blessed. I did as she said and then put the cross around my neck. I have never taken it off since.” Is Putin religious? In that case, he should believe in the existence of a soul? He has stated:

First and foremost we should be governed by common sense. But common sense should be based on moral principles first. And it is not possible today to have morality separated from religious values.

That does not sound very spiritual, rather practical and it is possible that Putin´s dealings with the Russian Orthodox Church is mainly motivated by political motives. Nevertheless, Kirill - or Vladimir Mikhailovich Gundyayev (his name as a private person) - who is the current Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, has declared that Putin's regime is "a miracle of God" and has furthermore stated that he and Putin share a vision of the "Russian world" as a sphere of common ideological values, which differ from those prevailing in the "West".

More than 75 percent of all Russians state that they are sympathetic to the Russian Orthodox Church and its close cooperation with the State. The Orthodox Church is not a state church and its funding is therefore dependent on private contributions, including those coming from influential politicians and oligarchs, or other sources of income, such as a recently unveiled scandal involving tax-free cigarette imports. A controversial financier of the Church is the millionaire Konstatin Malofeev, who also finances Russian separatists in Ukraine. Patriarch Kirill has ignored criticism that he is "politicizing" the Russian Orthodox Church and he has also had some trouble with persistent rumors accusing him of being a KGB informer during the 1990s.

Hillary Clinton did during her election campaign against Obama make fun of Bush's statement about seeing Putin's soul, it was when she spoke about Obama's inexperience of international relations and the danger of being too personal while dealing with foreign leaders. She said that Putin was not to be trusted and claimed that she could have told Bush where Putin's soul was because he "has been a KGB agent. By definition, he has therefore no soul ". Putin replied quickly: "The least we can ask is if a head of state has a head or not." Was this opinion directed against Mrs. Clinton, insinuating that she might have a soul but no head, or was it said as a recognition that Putin like Koščéj has hidden his soul and while exercising his powers only makes use of his head?

The discussion about Putin's potential soul continues. Last summer the US Vice President Joe Biden was interviewed in The New Yorker and he told about a meeting he had with Putin in 2011:

“I had an interpreter, and when he was showing me his office I said, ‘It’s amazing what capitalism will do, won’t it? A magnificent office!’ And he laughed. As I turned, I was this close to him.” Biden held his hand a few inches from his nose. “I said, ‘Mr. Prime Minister, I’m looking into your eyes, and I don’t think you have a soul.’ ” “You said that?” I asked. It sounded like a movie line. “Absolutely, positively,” Biden said, and continued, “And he looked back at me, and he smiled, and he said, ‘We understand one another.’ ” Biden sat back, and said, “This is who this guy is!”

Not that I became much wiser when I read Biden's description of his meeting with Putin, but I added it as another example of how much that is written about the Russian leader's personality seems to revolve around his psychic life and icy gaze.

I assume that Putin's soul, like Koščéjs, may actually be hidden away somewhere. The reason for such an assumption is that I have occasionally met with people who have been poisoned by the power they possess, blinded to such a degree that they apparently believed themselves to be flawless and all-knowledgeable, though they oddly enough at the same time felt both threatened and insecure and therefore are ready hurt and attack people they consider to be a threat to their image of excellence. The director Rainer Werner Fassbinder once made a film called Angst essen Seele auf, "Fear devours the soul." I think about the movie title and find it adequate, while I imagine that power also has a tendency to devour the soul.

In most cases, power seems to pose a threat to humanity, something I suspect is revealed in folk legends like those dealing with Baba Yaga and Koščéj. Power creates monsters. Evil is born when a feeling of all-encompassing authoritarianism is allowed to devour the soul.

Afanasiev, Aleksander (2014) The Complete Folktales of A.N. Afanas´ev, Volume 1. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. Brandenberger, David (2009) “A New Short Course?: A. V. Filippov and the Russian State's Search for a ´Usable Past´" in Kritika: Exploration in Russian and Euarasian History, Vol. 10, No. 4. Chandler, Robert (ed.) (2012) Russian Magic Tales from Pushkin to Platonov. London: Penguin Classics. Dawisha, Karen (2014) Putin's Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia? New York: Simon and Schuster. De Madariaga, Isabel (2006) Ivan the Terrible: First tsar of Russia. New Haven CT: Yale University Press. Gessen, Masha (2013) The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin. London: Granta Books. John, Andreas (2004) Baba Yaga: The Ambigous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. Littell, Robert (2009) The Stalin Epigram, New York: Simon and Schuster. Mandelstam, Osip (1989) Against Forgetting, edited by Carolyn Forché, translated by W.S. Merwin and Clarence Brown. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. Osnos, Evan (2014) “The Biden Agenda: Reckoning with Ukraine and Iraq, and keeping an eye on 2016”, in The New Yorker, July 28. Platt, M. F. (2010) “Allegory 's Half-Life: The Specter of a Stalinist Ivan the Terrible in Russia Today” in Penn History Review Volume 17 Issue 2. Politkovskaya, Anna (2004) Putin's Russia. London: Harvill.Propp, Vladímir Jakolevič (1968) Morphology of the Folk Tale. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press. Propp, Vladímir Jakolevič (1992) Le radici storiche dei racconti de magia. Rome: Grandi tascabili economici, Newton.Semyonova Tian-Shanskaia, Olga (1993) Village Life in Late Tsarist Russia (edited by David L. Ransel). Bloomington: University of Indiana University Press. Warner, Elizabeth (1985) Heroes, Monsters, and Other Worlds from Russian Mythology. New York: Schocken Books.