SOLARIS: A dreamed reality

After more than forty-five years, I once more watched Tarkovsky's film Solaris and was astonished to find that I still remembered several scenes. Actually, it may not be so remarkable. The film is about memories and I have some of my own linked to that particular movie.

To me, Solaris, like Tarkovsky's other works, is a multifaceted poem. I have difficulties with poetry. Most poems I have read do not fascinate me at all. I find many to be annoying, pretentious and self-explanatory. Verses describing the obvious, revealing trivial truths. Others are incomprehensible and thus useless, at least to me. They may have been hailed as masterpieces by an unanimous corps of reviewers, admiringly been quoted by friends of mine, read on the radio as Poem of the Day, or with a voice trembling with emotion been recited by connoisseurs sitting in one of the numerous sofas appearing in various TV shows. Nevertheless, most such poems leave me cold and unaffected.

Yes, I know – a genuine appreciation of true art often requires a carefully groomed sensitivity. Appreciation of complicated poems is frequently an acquired taste. Re-reading a poem a couple of years after the first encounter may reveal depths I did not discern during my first exposure to it. I recently read a collection of poems by the admired poet Katarina Frostenson, member of the Swedish Royal Academy

Tigris like night in the liquid that burns oil as threat

the mouth´s anus wreath transmits waves, promising rivers of blood

running across foreheads, worrying your entire body drives all heat from the room,

chasing out all sense sword crossing the air black participle

The poem is probably not bad. Perhaps it is masterful, maybe not at all. I do not know. De gustibus non disputandum est, in matters of taste there can be no disputes, though that truth does not hinder me from exposing my opinions, regardless of how stupid they might appear to be.

Perhaps it was somewhat unfair to quote Frostenson. I did it not as an example of how a poem´s rhythm and imagery do not work for me. They may impress another reader, with a life experience and sensitivity completely different from mine. Frostenson came to my mind since I recently read her collection of poems called Flodtid, “Time of the Flood”. Water flows through the entire collection, just as it does in Tarkovsky´s movies, though there the similarities cease. I cannot enter Frostenson's languages and pictures, they end up as stagnant water, failing to impress me.

What do then take hold of me? By a Swedish poet like Wilhelm Ekelund Ekelöf I find rhythms and thoughts speaking directly to my innermost being, opening doors to inner spaces where memories are kept. Images illuminating memories tinged with the colour and diversity of nature, producing not only joy but also melancholy, nurtured by worries and loneliness of moments long gone. An instant in life; a train journey, a monetary halt that making a lost world shining through the mist of the past, followed by evocative and crystal clear memories:

Then were the beeches bright, then was the stream

strewn with white buttercup islands, swimming;

bright its crown the bird cherry swung where as a boy I wandered —

Silently it rains. The sky hangs low on

thin crowns. A whistling; the train sets off

again. Into a slowly darkening evening, I travel friendless.

Thus writes a master. Here I find the picture flow, rhythm and musicality, just as they may appear in Andrej Tarkovsky´s movies. Good movies are often characterized by their rhythmic flow and the music they contain, here we find champions like Kubrick, Fellini and Tarantino. Movies may be likened to a chimera, a dream theatre, a fata morgana enclosed by dark rooms. In The Magic Latern Ingmar Bergman describes the mystery:

Film as dream, film as music. No form of art goes beyond ordinary consciousness as film does, straight to our emotions, deep into the twilight room of the soul. A little twitch in our optic nerve, a shock effect: twenty-four illuminated frames a second, darkness in between, the optic nerve incapable of registering darkness.

Peace and quiet, maybe even loneliness, are required to make me seriously become engaged with a novel, a poem, a piece of music. Solaris induced me to such a state of mind and I appreciate how Tarkovsky has pointed out the importance of dreams and memories. For me his film became a peep-hole to a universe of imagination. Ingmar Bergman has stated that film reflects the world in a manner similar to that of dreams.

According to Bergman, a great film's attraction is due to tricks performed by master magicians who have managed to create a parallel reality, the greatest of them all being Fellini, Bresson and Tarkovsky:

When film is not a document, it is dream. That is why Tarkovsky is the greatest of them all. He moves with such naturalness in the room of dreams. He doesn't explain. What should he explain anyhow? He is a spectator, capable of staging his visions in the most unwieldy but, in a way, the most willing of media. All my life I have hammered on the doors of the rooms in which he moves so naturally. Only a few times have I managed to creep inside.

In Solaris images flow, shift from black to white to colour, and back again. Pictures of running water over swaying weed, misty groves, rain showers are accompanied by the changing sounds of nature, while in a space station we hear the dull murmur of spinning electronics. Tarkovsky works as much with sounds as with pictures, action may occasionally be silent, while a dream sequence can be played against the background of a choral by Bach.

Time is an important actors in this dreamlike drama. We are sleeping and dreaming during one third of our lives. Dreams are some kind of transmuted memories. While we think and act, our minds produce thoughts that are not manifested in action or speech. Our senses, our eyesight and hearing do uninterrupted register impressions we hardly notice. During our hectic existence we usually lack time and opportunity to dwell in this unseen world, tossed around as we are by digital manipulations. In spite of this it is an undeniable fact that each and every one of us behind our skulls carry with her/him a universe of thoughts, memories, and ceaseless impressions. Above all we need concentration and patience to enter into these inner realms.

In the cold silence of infinite space we may be left to ourselves to a higher degree than when we are being immersed in the hectic whirl of earthly existence. At least that seems to be the case for the psychologist Kris Kelvin, who was sent on a mission to find out what was happening on a space station, which in a state of decay circles around a planet called Solaris, "From the Sun".

Kris finds the station to be largely abandoned. By its founding it was inhabited by crew of more than sixty men, though now all what is left is a skeleton crew consisting of two scientists, the third one, who had been a friend of Kelvin and whom he expected to meet, have taken his own life. The two remaining scientists are Dr. Snaut, an expert in cybernetics and Dr. Sartorius, astrobiologist. Both seem to be quite mad. Dr. Snaut turns out to be more friendly and accessible than the cynical Sartorius. When Kris repeatedly asks Dr. Snaut about what appears to be the presence of other creatures on board the station, the scientist stubbornly avoids to provide him with a straight answer. Kris assures him:

̶ Don't worry, I won't think you're insane.

Snaut answers:

̶ Insane? God, you know absolutely nothing. Insane... that would be a blessing.

What is really happening around them? It appears as if the minds of the two scientists have been “scanned” by the Solaris, which uses the information to create exact replicas of people populating the memories of Snaut and Sartorius.

From the space station´s observation deck, the two scientists and Kris are observing Solaris´s constantly changing surface; an ocean of a viscous, glutinous substance in perpetual motion, ceaselessly changing colour. The planet lives, but it is a form of life which is incomprehensible to the human mind. Solaris appears to be a giant organism, a kind of brain capable of materializing thoughts and memories. Currently it seems to use this capacity as some kind of defence fter the space station's scientists recklessly have bombarded the planet with harmful, radioactive particles. This unfortunate provocation gave rise to the appearance of the creatures who now share the crew's daily existence.

Memories and impressions they have of other individuals, being stored somewhere in their brains, are turning into “real” people of flesh and blood, with their own thoughts and a distinct emotional life. Perhaps Solaris aims to push the crew into madness. The individuals who are materialized from the scientists´ memories are all dead. What is even worse is that their demise may have been caused by the same people who now remember them and thus bring them back to “life”. The memory of people who have been lost to us in this manner remains stronger than all other recollections we nurture within us. Our selfishness, our strong and uncontrollable emotions, or our neglect, maybe even our ruthless cruelty plague us and for the space station´s crew members all these feelings are vividly returning to the in the form of the guests.

The cynical Dr. Sartorius, explains to Kris that the guests are no "real" people, even though they have an independent and solid appearance. Like our memories, they are timeless. They do not age, but remain as they are preserved in our memories. Howvere, they are not dreamlike. They are constituted by some kind of matter: "If we are atoms, then they are neutrons." The only way to get rid of them is to dissolve them in a "wrecker" that Sartorius have invented, capable of disintegrating the guests´ molecular composition. If you try to destroy the guests by killing them; poison them, send them into space, exterminate them by acid, this will only enable your thoughts, your memories, to replicate them again.

This appears far too absurd to be taken seriously, though both Tarkovsky's film and Stanislav Lem's novel, on which it builds, succeeds in making viewers and readers alike to accept the absurdism, just as we cannot protect ourselves from a dream. We enter into their world and if involved in the story our own our brain may be affected. However, for this to happen, patience and openness are required. Furthermore, we have to acknowledge that our memories exist, that they are capable of affecting us and our environment. They are an integral part of our lives, our reality. They are within us and cannot be eradicated. Especially not those memories that bother us the most. Memories of our own inadequacy, our greatest mistakes, the wrong decisions we have made, how we have been hurting our fellow beings.

The film progresses slowly. It takes time. A footage of a motorway in Osaka and Tokyo, seen through a car window, takes more than ten minutes. The movement of seaweed under a transparent water flow is patiently recorded, as well as a woman's gaze and changing facial expressions.

Calm and patience, without them the viewer cannot cope with the film, which, according to Tarkovsky's recipe for all his movies is "sculpted in time". He has described his craftsmanship as cutting away everything he found unnecessary from a huge block of time. What is left are sublime scenes filled with meaning and suggestions. They open up like Chinese boxes, each revealing details that bring us deeper into Tarkovsky's and hence our own dream world.

In a scene we find Kris, Dr. Snaut, Dr.Sartorius and Hari, Kris´s Dream Woman, his guest, in the space station's secluded library. A large room that has no windows and contains a lot of books and objects from times gone by; a large chandelier, Brueghel's paintings, busts of philosophers, globes, small statues ̶ a memory palace where each object has a meaning, a purpose. Here art and literature become replicas, just like the guests they constitute materialized memories. We look at objects, read books and enter our own memory worlds.

Dr. Snaut opens a large volume, Don Quijote, and finds a page telling how the usually confused and fanatical Don Quixote wakes Sancho Panza in the middle of the night, suggesting to his squire that he could make him the service to scourge himself as a favour to his good master and furthermore thus be helpful in delivering his beloved Dulcinea from the evil spell she is suffering under. The down-to-earth Sancho sighs: ”Señor, I'm no monk to get up out of the middle of my sleep and scourge myself.” As usual Don Quijote responds with a bewildering tirade of how grateful Sancho should be since Don Quijote, as promised, has succeeded in making his appreciated squire governor of an island and that he will soon make sure that his faithful servant will be ennobled and become a count. Does not Sancho think that a demonstration of a certain measure of gratitude would be worthwhile? Don Quijote interlards his speech with sounding words and Latin. Kris reads aloud how Sancho counters this tirade:

I don't know what that is, all I know is that so long as I am asleep I have neither fear nor hope, trouble nor glory; and good luck betide him that invented sleep, the cloak that covers over all a man's thoughts, the food that removes hunger, the drink that drives away thirst, the fire that warms the cold, the cold that tempers the heat, and, to wind up with, the universal coin wherewith everything is bought, the weight and balance that makes the shepherd equal with the king and the fool with the wise man. Sleep, I have heard say, has only one fault, that it is like death; for between a sleeping man and a dead man there is very little difference.

Don Quijote answers Sancho by stating that he has never heard him express himself so "elegantly".

The section from Don Quijote made me understand that the confused knight; the fantast, the dreamer, is a mouthpiece for the virtuoso Cervantes, as he throughout his novel demonstrates that the dream, the ideal, is more persistent than reason and science. Don Quijote, this mad idealist who perceives giants in windmills and princesses in robust maids, succeeds in bringing with him the practical Sancho Panza on their crazy adventures. Likewise, Tarkovsky and Cervantes make us believe in the seriousness of their creations. They make us understand that El Caballero de la Triste Figura, the Knight of the Rueful Countenance, in reality is a good man and why the psychologist Kris chooses to stay in the presence of Solaris to experience the painful presence of his dead wife.

Kris is lost in his memories, in his imagination. The art as a reflection of reality is after the reading of Cervantes illustrated by the camera´s absorption in a painting on the library wall - Breughel's Hunters in the snow. Accompanied by the space station's mumbling, electronic sounds, the camera sweeps across and occasionally lingers on the painting´s details. Images interspersed with Kris's childhood memories within a winter landscape. There he is a child in company with his young parents. After these excursions into memory and art, the camera returns to the space station's library. The muffled sound of engines is replaced by silence, broken by the clinking, clanking sound of the chandelier´s crystal pendants, followed by Bach's supernatural choral prelude (BWV 639) in F minor. We see how Kris and Hari weightlessly float around in the library.

Solaris is science fiction, but it denies science in favour of a dream world's brazen uncertainty. Dr. Snaut notes:

Science? Nonsense! In this situation mediocrity and genius are equally useless! I must tell you that we really have no desire to conquer any cosmos. We want to extend the Earth up to its borders. We don't know what to do with other worlds. We don't need other worlds. We need a mirror. We struggle to make contact, but we'll never achieve it. We are in a ridiculous predicament of man pursuing a goal that he fears and that he really does not need. Man needs man!

Solaris deals with the "little life", opposed to the infinity of the universe. It is about human relations. What we people do with and against each other. How we seek love and security with those we want to be with, but how this endeavour may hurt those we should love.

Kris Kelvin's guest at the space station is his dead wife Hari, who died ten years earlier by a self-administrated poisonous injection. On her left upper arm she still carries the small mark after the syringe needle´s puncture. It was her everyday anguish about the sincerity of Kris´s love and his prioritization his own career that finally broke down their relationship and drove Hari to bottomless despair. Of course does the experience of his wife's suicide constitute Kris´s strongest and most painful memory.

Nevertheless, what he remembers even better than his sorrow and despair is the love that once enchanted him, Hari´s beauty, her vulnerability and compassion. At the space station his ideal image of his beloved and lost Hari is displayed. Dreamy, beautiful and gentle, yet delicate and uncertain about who, or what, she really is, the guest Hari beguiles Kris even more than the living Hari could ever be capable of.

Kris´s memories are gradually restoring Hari´s lost character and through associations and her co-existence with Kris and his colleagues she is becoming an increasingly complete human being. Eventually, Hari is even able to recreate memories that Kris has forgotten. For every day, Hari becomes more and more alive, increasingly independent. Because Hari is not driven by any sense of self-assertion or prestige and solely wishes to deserve the love of Kris, she eventually becomes the wisest, most sensitive and hence the most human being of the space station.

Kris's love for his guest Hari becomes even greater than the one he had for the real Hari. He confesses: "To me, you mean much more than any scientific truth." By the beginning of their relationship Kris had been unable to accept that this dream woman was "real". That she could be identical to his lost Hari. He tried to isolate and destroy out his guest. Kris tricked the loyal Hari into a spacecraft and then expelled her into the emptiness of space. However, she returns. When Kris isolates Hari or tries to hurt her, she suffers, but when she returned after his attempt to get rid of her, she is like a new Hari, without memories of how Kris earlier on had tried to eliminate her.

Kris´s and Hari's anguished relationship; her steadfast and uncomplaining love, paired with Kris´s inconsiderate cruelty, his assumption that he could never be able to love a projection of a dream and he thus treats her like an insensitive creature, made me think of a hit song by Allan Roberts and Doris Fisher, which Mills Brothers sang in their mellow manner:

You always hurt the ones you love,

The one you shouldn't hurt at all.

You always take the sweetest rose

And crush it until the petals fall.

You always break the kindest hearts

With a hasty word you can't recall.

And if I broke your heart last night

It's because I love you most of all.

I read the novel before I saw the movie. At that time I studied in Lund and lived in a student corridor, which meant that twelve students lived in a room of their own with a toilet, while sharing shower, telephone cabinet and a kitchen. I enjoyed the corridor life and made several good friends there. By the time I read Solaris, I had met a young lady from one of the coastal towns of my home region, Skåne, she was a nurse. We met quite often, but did not live together. It was a rather intense, sensual relationship. We enjoyed being together, but I was painfully aware of the fact that I did not love her enough and even though I did not tell her the truth, she realized it and tried to tie me closer to her, something that gave me an even worse conscience. I wanted to love her, but I could not. To make things worse we were too close to each other to be just friends. Before it went too far I had to put an end to the relationship. But how? I liked her and did not want to hurt her.

At times I was with her in her hometown and she with me in Lund. For me it was a rather confusing, even aggravating existence. My time schedule was highly irregular. Simultaneously, I studied History of Religions and Drama, Theatre, Film, worked as a waiter on the train restaurants between Malmö and Stockholm, which meant that I slept over in Stockholm a couple of days in the week and during the weekends I visited my friend, or she came over to me.

While I was reading Stanislaw Lem's Solaris, I was struck by two strange episodes. The corridor was like the hallway of a space station by which the astronauts slept in their own rooms, decorated to their liking and taste. Like them, I and my corridor friends shared common spaces and interacted daily. Like the crew in Solaris´s Space Station, each of us lived both common and different lives, and like them we also had guests, often from the past; relatives and old friends. However, the great difference was that in their space station the crew members received visits from guests who were materialized memories of people they had hurt and who had died due to the misery they had created.

One night I woke up with a jolt and found that in the darkness a creature sat in the armchair opposite me, staring intently at me. It was not a human being, rather a demon. I hurried up to the armchair, just to find the pile of the bedspread and my clothes. I assumed that it was my reading of Solaris that had influenced me and during the seconds between sleep and awakening my consciousness had been lingering at the threshold between dream and reality, creating the image of an unwelcome guest.

A few nights later I suddenly woke up again. Next to me lay my friend. She opened her eyes and smiled at me. I smiled back and tenderly stroked her across the cheek. It was soft and tangible, yet I thought, "What if she's not real? Perhaps she's just a guest." When she had fallen asleep again, I carefully studied her relaxed face. She was sleeping safely beside me. She was not a guest. I lay with my back against the wall and to get down on the floor I have to gently step over her, careful not to wake her up.

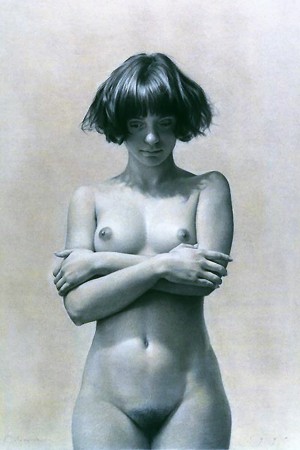

I tip-toed to the toilet, opened the door and switched on the light. To my great astonishment she was inside the toilet. Naked, facing me. At first she stood with her arms crossed under her breasts, looking down towards the floor, but then rose her head, looking straight into my face, smiling at me at the same time as she lowered her hands and said: "Jan, here I am." The strangest thing was that she stood with her feet in the lavatory pan. Somewhat terrified I realized: "Then she was a guest after all!" I shook my head, shut my eyes and when I opened them again I saw that she was no longer there. I rushed back into the room, the bed was empty.

I watched Tarkovsky´s movie a few years later. My friend had left then, it was somewhat sad, but the regret was soon forgotten. We left each other friends. I watched Tarkovsky's movie on the TV in my parents' home, together with my father and we both became quite fascinated. When we talked about the film afterwards, we agreed that, like dreams and memories, it had radiated both proximity and alienation. The same feeling as when we watched the Super 8 movies that my father used to shoot during my childhood.

Several years later we sat on the second floor wind of my parents' house; Mom, me, Rose and our girls. My youngest suddenly became sad and I when I wondered why she answered: "It's so weird and sad. There you are younger than me and at the same time you sit beside me and are much older than I am."

In Tarkovsky's movie there are recurrent flashbacks depicting images from Kris Kelvin's childhood. We see his father and mother and himself at the same age as we have seen him before, but he also appears as a little boy. Is it really flashbacks we are confronted with, or just projections of Kevin´s distorted memories? There is a short beautiful, scene with a girl smiling at a boy. The same loveable, maybe even mysterious smile that Hali (interpreted by the mystifyingly stunning Natalja Bondarĉuk) occasionally reveals when she is together with Kevin in the space station. Is the girl in Kris's memory an image of Hari as a small girl?

My father's family films contain long sections of nature images; leaves, forests, streams, garden flowers. Tarkovsky's Solaris also allows the camera to linger on clear water flowing above swaying water plants, flower meadows, misty oak groves. Thus we perceive the poetry of Tarkovsky's workmanship and over and over again water appear in its different shapes; like a flowing stream, a calm water surface, rain ̶ just as in Ekelund's short poems I quoted above, " the stream strewn with white buttercup islands, swimming" and water appears again a row further down "silently it rains.” Tarkovsky stated:

There is always water in my films. I like water, especially brooks. The sea is too vast. I don't fear it; it is just monotonous. In nature I like smaller things. Microcosm, not macrocosm; limited surfaces. I love the Japanese attitude to nature. They concentrate on a confined space reflecting the infinite. Water is a mysterious element -- because of its structure. And it is very cinegenic; it transmits movement, depth, changes. Nothing is more beautiful than water.

Everything flows, you cannot step into the same river twice, yet water is permanent, it only changes shape, we drink the same water as people drank thousands of years before us.

The rain pours down during Kris Kelvin's visits to his childhood home. During his meetings with his father. As I remember, there are no childhood memories in Stanislaw Lem's Solaris. It deals more with the impossibility of understanding what is strange to us, like the planet Solaris and its ability to influence our thinking, how it makes use of of our inner selves to create a reality that might benefit its own purposes.

Tarkovsky, who was deeply religious and has in an interview recalled:

When I was very young I asked my father, ‘Does God exist—yes or no?’ And he answered me brilliantly: ‘for the unbeliever, no, for the believer, yes!

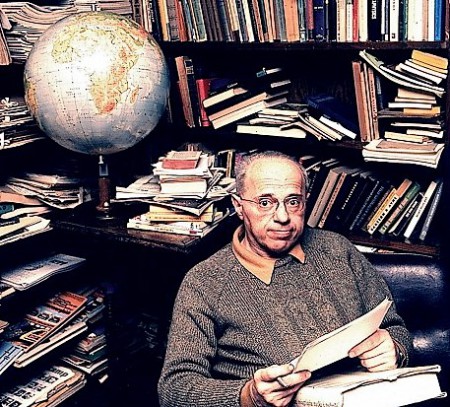

Perhaps Lem´s Solaris and Tarkovkijs´s Solaris tackle the same problem from two very different angles, where Lem might possibly be the non-believer and Tarkovsky the believer. Lem was a seeker who had lost his faith in a God who cares about each and every one of us. His family had survived the inferno of Nazi oppression in Poland, something that certainly had left deep wounds in Lem:

During that period, I learned in a very personal, practical way that I was no "Aryan". I knew that my ancestors were Jews, but I knew nothing of the Mosaic faith and, regrettably, nothing at all of Jewish culture. So it was, strictly speaking, only the Nazi legislation that brought home to me the realization that I had Jewish blood in my veins.

During the war, Lem worked as a mechanic with fake papers, after the war he studied medicine, but did not graduate to avoid being drafted into the Polish army. All medical doctors had to do military service. By that time, his experiences of repressions, combined with scientific studies had made him loose his faith in God:

for moral reasons ... the world appears to me to be put together in such a painful way that I prefer to believe that it was not created ... intentionally.

In his novel Lem allows scientific research of Solaris, solaristics, to change into something that may be interpreted as an almost religious search for an explanation of the unimaginable, the incomprehensible. Human existence as a pursuit of a goal that can never be reached:

It is faith wrapped in the cloak of science; contact, the goal for which we are striving, is as vague and obscure as communion with the saints or the coming of the Messiah. Exploration is a liturgy couched in methodological formulas; the humble work of researchers is the expectation of consummation, of Annunciation, for there are not nor can there be any bridges between Solaris and Earth.

Lem mulls over the incomprehensible. He regards the limited existence of man in relation to the infinity of the universe, its incomprehensible greatness. Stanislaw Lem ponders about at the sea and does not find it to be, as Tarkovsky does - monotonous. For Lem, the sea is deep, large and unfathomable - like the universe. While facing the staggering incomprehension of the Universe, faith in a personal God becomes trivial, absurd.

Lem criticized Tarkovsky's interpretation of his Solaris, perceiving the film as a misconception of his intentions. Stanislaw Lem writes about Kant, who assumed that we humans are limited by our own thinking, the "categories" we use to understand our world and existence. Therefore, we cannot find the answer to the mystery of life, the Thing-in-itself, which is far beyond all human understanding. Our thinking can only circle around a concept like the Thing-for-me, our own little microcosm:

Because there exists the Ding an sich, the Unreachable, the Thing-in-Itself, the Other Side which cannot be penetrated. But in my prose this was made apparent and orchestrated completely differently.

What made Lem annoyed was that Tarkovsky brought in his parents into the story, "even an old aunt he had," especially Tarkovsky's introduction of the Mother Figure made Lem disheartened. He had not intended his novel to be “a family” story and considered Tarkovsky´s movie to be a movie a film about "erotic problems of people in outer space". What Lem had tried to portray was what makes a human to a human, suggesting that there may be something infinitely greater than our limited consciousness, completely incomprehensible for our intellect.

All that has for me a religious tinge. It seems to me that Lem almost unknowingly approaches Tarkovsky's appreciation of Solaris as a religious epic. Lem's description of how he wrote the book in 1961 makes it appear that he wrote the novel in some sort of trance, like medieval saints claiming that they wrote their books under divine inspiration: "The novel poured out of me."

Tarkovsky approaches Solaris's mystery from another direction than Lem. It is not the ocean he perceives, but his own history of sorrow and happiness. He appreciates the mystery from a human point of view. How each of us perceives her/his own, personal life, our limited existence. The film's introduction is puzzling in all its diversity.

First, we see a brook with gushing, crystal clear water and then a man we later understand is Kris Kelvin, who walks through a blooming, though misty, meadow. In one hand he clutches an electronic device, which he puts away as he approaches his parents' home. From a distance he notices how a car stops, a man and a little girl get out and are welcomed by Kris's father, a little boy runs towards the visitors. The man, who is enthusiatically greated by Kris´s father, is Berton, an astronaut who has visited the space station by Solaris. Already here we find some reasons for confusion. Kris appears to be somewhat detached from what is happening around him and we wonder who the little boy and girl are. They seem to be important for the story, but only moves around its fringes.

Soon a movie appears within the movie. Berton has brought with him a tape recording, some kind of DVD, which in a black and white presents how he, as a significantly younger man, is being questioned by an international expert committee. We are supposedly watching happenings in the future, but the movie is black and white and the men are dressed in tie and suit, customary in the early seventies. In the film recording, which has a documentary character, Berton tells about what he has seen and experienced at Solaris´s Space Station. Causing disbelief among the experts, he asserts that above Solaris's ever changing surface, he has seen a three-meter-long new-born infant. What he claims to be his documentation of the event is displayed. However, what we perceive of Berton´s film is nothing else but Solaris's remarkable, swirling surface. By all, except a foreign expert, Berton's experiences are rejected as hallucinations. The foreigner claims that, even if Berton´s film did not show his vision of a huge child, what he has experienced can nevertheless not be dismissed and may actually have been caused by external phenomena worthy of further scientific examination.

Tarkovsky´s pictures move back and forth from the black and white of Berton´s DVD to the spectators' reactions within a living room filmed in colour. We see how an annoyed Berton restlessly wanders around, occasionally pausing to watch himself as he appeared twenty years earlier. Kris's father does not watch the DVD, Kris is sitting in his place. After the documentary Kris and Berton walks outside, where Kris claims that Berton's experiences lack scientific proof. Utterly upset Berton leaves the house and drives away with his daughter, who now looks completely different than before.

After a while, Berton calls from his car through some kind of mobile phone camera. He explains that the big infant he had seen materialized above Solaris´s surface actually was the decesed son of one of the crew members. Berton did not know this until recently when he visited the crew member´s wife, who now was a widow and showed him a photo of her dead child, of the same age and the same looks as the child he twenty years earlier had seen above the surface of Solaris. Berton turns silent, looking absentmindedly ahead, though we still see him and his daughter in what appears to be an ordinary car. After a while we realize that Berton is sitting with his arms crossed and that the car apparently is driverless.

A long sequence follows, accompanied by motor noise, through the car window we follow a motorway across Japanese cities. The effect is similar to the one conveyed in the introductory images of flowing water, but now we are in a completely artificial environment. However, both settings have an almost hypnotic effect on the viewer and the transition from a highway to a spacecraft docking into a space station appears to be completely consistent and natural.

My somewhat bewildering description of the film's introduction was intended to serve as an indication of Tarkovsky´s technique; his use of sound, angles, filters and other artifices of his trade. Film is both technology and message, intimately depending on each other. Image follow upon image in a specific rhythm, dream and reality mix, the familiar and the unknown exist side by side. Describing Tarkovsky´s approach to film making feels quite futile. A description of something that ought to be experienced instead.

His dreamy, multifaceted film seems to be about entering and immersing oneself in different worlds - space, art, music, the future, the past, but mostly in yourself, your inner sphere where your memories mix with reality, where your limited existence becomes part of something much greater. This is poetry to me. But, maybe not for you. It depends on who you are. Your experiences, your specific background. Like Katarina Frostenson's poem that may speak to others, but remains silent for me.

Solaris, the novel and the film, have become part of my memories, and there they live, like Gunnar Ekelöf's poem Euphoria:

As if were the last evening before a long, long journey:

You have the ticket in your pocket and finally everything is packed.

And you can sit and sense the nearness of the distant land,

sense how all is in all, both its end and its beginning,

sense that here and now is both your departure and return

sense how death and life are as strong as wine inside you!

Bergman, Ingmar (2007) The Magic Lantern: An Autobiography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Cervantes, Miguel de (1981) Don Quixote: The Ormsby Translation, Revised Backgrounds and Sources Criticism. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. Ekelund, Wilhelm (2004) The Second Light, translated by Lennart Bruce. New York: North Point Press. Ekelöf, Gunnar (1982) Songs of something else: Selected poems by Gunnar Ekelöf translated by James Larson and Leoard Nathan. Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press. Gianvito, John (2006) Andrei Tarkovsky: Inteviews. Jackson MS: University Press of Mississippi. Green, Peter (1993) Andrei Tarkovsky: The Winding Quest. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Lem, Stanislaw (2002) Solaris. Wilmington MA: Mariner Books. Lem, Stanislaw (2018) Stanislaw Lem – The Official Site, https://english.lem.pl

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)