SPIRIT OF PLACE: Magic Prague

In an earlier blog post, I wrote that my oldest daughter once told me that Rome lives a life of its own. If people disappeared from that town, there would still remain an unexplained presence. I think she was right. In other big cities, like New York, Paris, London and Stockholm, I have not felt such a mysterious presence as I sense in Rome. However, it feel it in town city whert Janna lives for the moment. Prague also breathes and lives. Perhaps that town's power and influence is even greater than what is the case with Rome. When Gustav Meyrink in his novel The Golem wrote about Prague it appears as if the town dominates its inhabitants and not vice versa.

[I turned my attention to the] discoloured houses squatting side by side before me in the rain like a row of morose animals. How eerie and run-down they all looked! Plumped down without thought, they stood there like weeds that had shot up from the ground. They had been propped against a low, yellow, stone wall—the only surviving remains of an earlier, extensive building—two or three hundred years ago, anyhow, taking no account of the other buildings. There was a half house, crooked, with a receding forehead, and beside it was one that stuck out like a tusk. Beneath the dreary sky, they looked as if they were asleep, and you could feel none of the malevolent, hostile life that sometimes emanates from them when the mist fills the street on an autumn evening, partly concealing the changing expressions that flit across their faces.

I have lived here for a generation and in that time I have formed the impression, which I cannot shake off, that there are certain hours of the night, or in the first light of dawn, when they confer together, in mysterious, noiseless agitation. And sometimes a faint, inexplicable quiver goes through their walls, noises scurry across the roof and drop into the gutter, and with our dulled senses we accept them heedlessly, without looking for what causes them.

Often I dreamt I had eavesdropped on these houses in their spectral communion and discovered to my horrified surprise that in secret they are the true masters of the street, that they can divest themselves of their vital force, and suck it back in again at will, lending it to the inhabitants during the day to demand it back at extortionate interest as night returns.

In one of his short stories, Humming in the Ears, written by the beginning of the last century, Meyrink connects the ailment called tinnitus, i.e. that you without external influence hear sounds that may be described either as a constant beeping, a deep bass sound or muffled noise, a phenomenon which, according to Meyrink, in Prague originates from the town´s hidden depths.

In the district known as Kleinseite there stands a gloomy old house "buried up to its belly in the ground." In the basement you will find a dark and narrow shaft covered by an iron trapdoor, if opened you might gaze down into a bottomless pit that oozes with moisture. In the past, people have let down torches tied to on a line. Right down into the darkness, the light becoming darker and smokier, until it goes out altogether. People have said: “There is no more air." However, “he who has eyes to see can see without light, even in the darkness, when others are asleep.” Meyrink knows that before people fall asleep after a hard day´s work, thoughts are born from disappointment, vengeance and greed. When bitter and exhausted people finally fall asleep, snoring and drooling, phantoms of greed are born from such thoughts. They slither and slide trough joints and doors until they end up in the old house where they sink into the dark shaft. At its bottom stands Satan's whetstone, whirling unceasingly, day and night. If you plug your ears, you can hear it, humming away inside you.

The notion that Prague within its buildings breeds and hides forces that might take control of residents and temporary visitors turns up in several books that find their origins in the city. Kafka loved and hated the town that had shaped his identity and influenced his life. Often he could feel as if it limited his horizon and thoughts. In 1902 he wrote to his friend, Oskar Pollak:

Prague doesn´t let go. Either of us. This old crone has claws. One has to yield, or else. We could have set fire on it on two sides, at the Vyšehrad and at the Hradčany; then it would be possible for us to get away. Perhaps you´ll give it some consideration up to Carnival time.

I cannot help but interpret Kafka's recurring depictions of closed rooms, underground passageways and suffocating architecture from arising out of his sense of confinement, produced by Prague's cramped houses and narrow alleys. In the short story Description of a Struggle Kafka's alter ego nightmarishly staggers between named places in and around a nightly Prague. As in a short story by Meyrink the surroundings occasionally invades or coincide with the narrator's inner being. It is as if he intermittently and willfully is controlling his environment, and vice versa - let himself be guided by it. Infrequently he is seized by a liberating feeling, an expansion that lifts him up and out of the city's suffocating presence. Having lost sight of his companion he slips and falls down on a patch of ice in the Crusaders´ Square, where he for several minutes is left lying while he fascinated watches his surroundings. When he vacillating is back on his feet again, he blissfully open his arms as if to embrace the moon, making swimming strokes and with incredible ease moves forward while his head "rests" freely on the cool evening air.

By the mid-seventies, Prague´s oddities entered my own life. At that time I had with my comrades visited the town once or twice, but it was in Malmö I was reached by its strange ghosts. For some now-forgotten reason I found myself in that metropolis of southern Sweden and had in a bookstore bought a translation of Meyrink´s Golem. Several years earlier I had in All Världens Berättare, Storytellers from the Entire World, a magazine that my father subscribed to, with fascination read Meyrink´s short story The Watchmaker. What grabbed me in that tale was its peculiar mixture of realism and fantasy, how inner thoughts influenced and mixed with extrinsic impressions in such a way that a parallel universe was created.

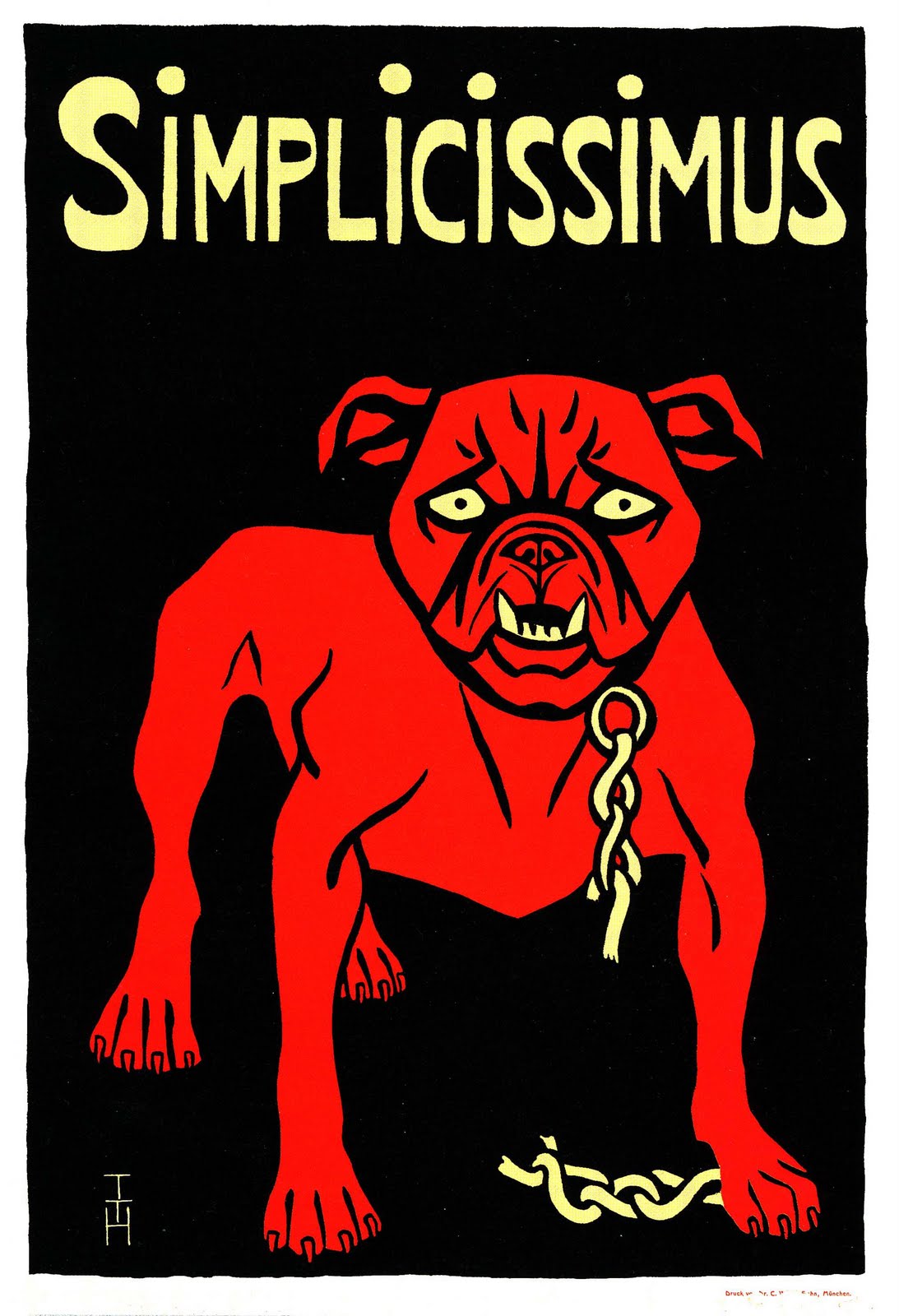

Meyrink was a remarkable man, like many mystics before him he was both a dreamer and a practical man; banker, skilled fencer, a rower among the international elite and an elegant snob, at the same time he was knowledgeable about most things concerning religion and occultism, practiced yoga and meditation daily and was not the least one of the most successful writers of his time. Between 1901 and 1908, he published in the German magazine Simplicissimus 53 short stories, a contribution that was a major reason to an increase in the magazine's circulation. Simplicissimus was read and discussed among German-speaking intellectuals throughout Europe. Perhaps its brash and uninhibited tone, achieved through excellent writers and talented cartoonists, somewhat pointedly can be sopared to the French Charles Hebdo. Though Simplicissimus had a greater international reach and a much higher artistic level than the French satirical magazine.

I began reading my newly purchased Golem sitting alone in a café in Malmö and became so involved that I forgot time and space. In Lund I had made an appointment with my friend Stefan and on my way to the train station I rushed into a phone booth to give him a call excusing myself for my late arrival. Stefan's phone number is one of the few I know by heart and I dialed it without thinking. My surprise was therefore great when I from the handset heard Margarete Hasslow´s voice:

- No, Jan, this is not at Stefan. You've come to the house of pastor Hasslow. Anyway, I may greet you from your father; I just met him now with Göran.

Completely taken aback, I stared at the phone. The Hasslow family lived in Hässleholm and not at all in Lund. I had never phoned to them and when I later looked up their number, I found that it was completely different from Stefan´s. Göran Hasslow was one of my father's best friends and when I called that day he was laying on his death bed. However, I had not thought about pastor Hasslow´s agony when I dialed the number. And even stranger - when I a few days later came for a visit to my childhood home in Hässleholm, my father unexpectedly told me:

- I thought about you a few days ago and bought this book for you.

It was the The Golem by Meyrink.

When I during a weekend a few weeks ago visited my oldest daughter in Prague, we went to museums, the theater and a concert. We saw Jan Schwankmeier´s remarkable creations inspired by Emperor Rudolph II's Wunderkammer with its freaks and other curiosities, and Frantisek Kupka´s amazing Cathedral Paintings inspired by his esoteric notions. We went to the castle of Hradčany, the Alchemists’ Alley and Peter Parler´s Cathedral, but most of the time we wandered the streets.

In the evenings and at night, when the tourists have disappeared into hotels and taverns, while the fog crept in from the Vltava´s gushing waters and muted the light of the streetlamps that glowed in narrow streets, we felt that the old city was breathing and understood why it had captured the souls of so many writers and artists.

The poet Reiner Maria Rilke, who like Kafka was born and raised in Prague, could like him and Meyrink connect Prague residents with inanimate objects; such as furniture and houses. Rilke described the people of Prague as being circumscribed by the heavy, enigmatic furniture that cluttered the city's messy apartments. It was as if their past was kept alive in their chairs, wardrobes and pictures. “Their small rooms, three floors up”, were imbued with their remarkable past. The faces of Prague´s inhabitants had inherited their expressions and emotions from some forgotten ancestors and “their weak hearts” could hardly bear the weight. In a letter to his mistress, Lou Andreas-Salomé, who had been Nietszche´s great, but unconsummated love, Rilke wrote that the people of Prague:

are like corpses who cannot find peace and therefore in the dark of night live their dying again and pass one another by across the hard graves. They have nothing left: the smile has wilted on their lips, and their eyes have drifted off their last crying as if they were floating on twilight rivers. All progress in them amounts only to this: their coffin rots and their clothes disintegrate and they themselves crumble and grow wearier and lose their fingers like old recollections. And they tell each other the story of this in their long-dead voices: that´s how the people of Prague are.

Prague is often associated with its Jewish cemetery, which for 300 years was the only graveyard permissible for Jews. It was established in 1478 and is still not much larger than it was during the Middle Ages. Lack of space forced the Ghetto´s inhabitants to bury their dead on top of each other, up to twelve layers deep. Today there are more than 12 000 gravestones within the limited area and beneath them are more than 100 000 people buried.

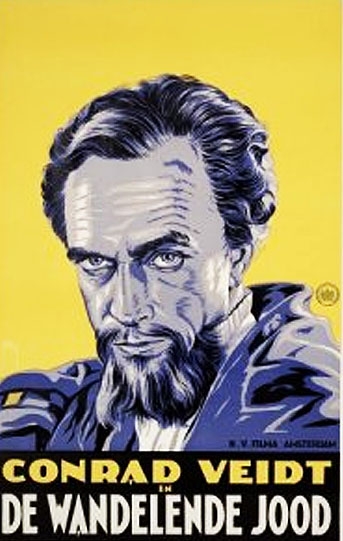

The second-rate author Herrman Goedsche, who after an incident of blatant forgery had been dismissed from the Prussian Post Office in Berlin had become partner in an ultra-conservative newspaper, wrote under the pseudonym Sir John Retcliffe in 1868 a historical novel called Biarritz. A significant part had been plagiarized from a satirical book by the French author Maurice Joly, in which Machiavelli and Montesquieu meet in Hell to discuss various methods to destroy humanity. However, Goedsche added one crucial episode - instead of placing the diabolical plans in the mouths of famous, dead authors, he created the fiction that an anonymous witness, hidden among the gravestones of the Jewish Cemetery in Prague had observed how the Supreme Council for the Twelve Tribes of Israel at midnight had assembled, as they did every hundredth year, to discuss the success of their ongoing takeover of world domination and their future plans to achieve this goal. The meeting was attended by no less than The Wandering Jew. The chairman, a rabbi named Levit, declared that the Jews would almost certainly achieve their goal within the upcoming hundred years.

Members of the Russian secret service in Paris lifted the rabbi's speech from the novel, translated it into Russian and under the impression that it was a reliable report of an international Jewish meeting in Prague they sent it to their employers in Petersburg. The “report” was circulated throughout the Russian Empire. Sergei Nilus, a religious zealot and anti-Semite, translated some French pamphlets and adapted them to the alleged police report, thus he produced a book which he called Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Now all the guise of fiction was gone and the book was sold as the official minutes of the putative cemetery meeting in Prague.

Nilus´ concoction was translated into a variety of languages and was quickly spread across the world. I bought my newly printed Spanish edition in a pharmacy in Santo Domingo and I have since then seen the book in different parts of the world. In countries like Egypt and Iran, it is still a bestseller. Needless to say, this miserable fabrication was a big hit in Nazi Germany, where it often was distributed for free.

The Protocls of the Elders of Sion might be regarded as the most infamous poisonous flower of what would become known as “The Magical Prague.” A mysterious place where alchemists, magicians and Jewish cabbalists communicated with demons and angels, casted horoscopes, mixed poison, made gold and created homunculi, i.e. artificial creatures and people. Especially around the beginning of last century an entire literary genre thrived around ancient Prague, Europe's enigmatic heart.

An interesting, but somewhat confusing representative of this literary specificity is Francis Marion Crawford's The Witch of Prague, written in 1890. Marion Crawford had some similarities with Gustav Meyrink. He was an artistically gifted cosmopolitan, born in Italy to American parents and a connoisseur of oriental mysticism - he had studied Sanskrit, both in India and at Harvard - and not the least, the scope of his literary production consisted of intricate horror stories, some of which are still quite scary.

In The Witch of Prague several odd characters sneak around among the crumbling tomb stones of the Jewish cemetery; including an undersized and extremely talkative Arab, who experiments with mummies and tries to revive corpses, he is sometimes joined by a handsome Jew who spies on the beautiful witch Unorna, who also tend to stick around among the tombs.

At the center of the story is a man only known as ”The Wanderer”. The novel kicks off in an ancient house surrounding a lush orangery, where The Wanderer meets Unorna, "The Witch of Prague", who like him is looking for "true love". While she is courted by Israel Kafka who is madly in love with her, Unorna becomes infatuated with The Wanderer, who nevertheless is on the hunt for his own lost love - Beatrice, who without his knowledge by her cruel father has been relegated to a monastery. The Wanderer is described as endowed with a rather evasive nature, while the young Kafka seems to have an apparition and character quite unlike his more famous namesake, Franz.

In form and feature the youth represented the noblest type of the Jewish race. It was impossible to see him without thinking of a young eagle of the mountains, eager, swift, sure, instinct with elasticity, far-sighted and untiring, strong to grasp and hold, beautiful with the glossy and unruffled beauty of a plumage continually smoothed in the sweep and the rush of high, bright air.

The lofty and flowery style gives an indication of Crawford´s often pesky means of expressing himself, even if the novel can infrequently be quite fascinating it all too often turns into a stringy encyclopedia of history and occultism, or is weighed down by long-winding dialogues. There are however impressive glimpses of an eerie and dilapidated Prague:

The winter of the back city that spans the frozen Moldau is the winter of the grave, grim as the perpetual afternoon, cold with the unspeakable frigid mess of a reeking air that thickens as oil but will not be frozen, melancholy as an island of death in a lifeless sea.

Like so many other authors and poets Crawford imbues Prague with a life of its own life. Like when the Wanderer for the first time approaches Unorna´s residence:

The windows of the first and second stories are flanked by huge figures of saints, standing forth in strangely contorted attitudes, black with the dust of ages, black as all old Prague is black, with the smoke of the brown Bohemian coal, with the dark and unctuous mists of many autumns, with the cruel, petrifying frosts of ten score winters.

The mysterious Prague has received its powerful image in the Golem, which according to the legends was created in 1580 by Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezael. Of clay taken from the brinks of Vltava the rabbi shaped a creature that was much larger and stronger than a common man. Into the mouth of his creation he stuck a piece of parchment on which he had written a shem, a formula consisting of one of God's secret names, when the word emet, truth, was added to God's name the rabbi gave life to his Golem (the Hebrew term for something that is shape- and soulless).

Golem worked as a servant in Rabbi Loew´s household. He is said to have been a nice fellow, somewhat awkward, though always obliging. The creature was unable to speak, but understood everything it was told to do. Every Sabbath, Rabbi Loew removed the patch of paper inscribed with Golem´s shem and the creature was thus transformed back to being a huge, lifeless lump of clay. However, one Sabbath Rabbi Loew forgot to remove the shem and the uncontrollable Golem ran and amok destroying everything in its path, until Rabbi Loew managed to dislodge the shem from the monster's mouth, erase the “e” from the word emet, which thus became met, death. Loew then returned the patch of paper into the Golem´s mouth and together with his Jewish brethren he stored it in the attic of the Old-New Synagogue, where it still remains to be brought back into life it the ghetto inhabitants are threatened with destruction. Golem is namely invulnerable and able, on his master's command, to kill all that comes in his way.

Even if the Golem rarely shows up in Meyrink´s novel with the same name - he is by the way quite different from the huge hulk of the legend - his spirit looms over the story in which he becomes a personification of Josefov, Prague's Jewish ghetto. The elusive figure is in fact the city's spirit and consciousness, inarticulate but always present. The story turns into a vision that affects the protagonist after he has mixed up his hat with the one that thirty years earlier was worn by a certain Athanasius Pernath, thereby Pernath´s previous existence steals into the protagonist's already unstable reality - he has spent a long time locked up, apparently in a mental institution - and, like him, the reader becomes uncertain if what is happening to him is an illusion or reality.

When I read the novel I was reminded of another reading experience - Roland Topor´s The Tenant, in which a man imagines himself to be another person, namely a woman who previously lived in the same apartment, and committed suicide there. I am convinced that Topor must have been inspired by Meyrink´s Golem, both novels share the same eerie suggestive dreamlike atmosphere and deal with how the environment breaks into a person's consciousness. Roman Polanski's film version of The Tenant is very close to the literary original.

However, Paul Wegener's film from 1920, Golem: How He came into the world, is not at all as often has been claimed, a film version of Meyrink´s novel. It is based on the older legends surrounding the Golem. What Wegener's film has in common with Meyrink´s vision is the great importance the surroundings have for creating the atmosphere of the story. The film takes place entirely within the confines of a make-believe landscape created by the visionary architect, painter and stage designer Hans Poelzig and becomes an important protagonist in a story that can hardly be described as eerie, but rather as a multifaceted, aesthetic representation of a condition characterized by alienation and unpredictability.

As mentioned above, it may happen that Golem and Prague break into my life. When I lived in Paris, I once more read Meyrink´s The Golem and his remarkable short stories, I also got hold of Topor´s The Tenant. Since I lived alone in a small apartment in a big city where I only partially understood the language it was not difficult to identify with the protagonists of those stories. During one of my daily walks through the often rainy Paris I entered a second-hand bookstore and at random bought a novella by Guillaume Apollinaire, Le Passant de Prague and found that it was about a strange meeting in Prague. With my bad French I struggled through it and am going to give an account of the content, but before that I shall briefly describe a meeting in Prague that made me think about that particular book and inspired me to write this blog post.

My main reason for visiting my daughter in Prague was that she took her master's degree as set designer at DAMU, The Theatre Faculty of the Academy of Performing Arts. After the festive ceremony, I had dinner with Janna and a couple of her friends at a small restaurant right in front of one of Prague's many Baroque churches. With us was an ethereal and peculiarly dressed lady of thirty-five. She was a Czech artist named Astrid Sourkova, but she had for several years been living in Berlin where she had taken Habima Fuchs as her artistic name. Habima was probably what I by using a Yiddish expression would call a Luftmensch, i.e. a person who with great dedication pursues airy, intellectual pursuits than dedicate herself to more practical tasks like securing a decent income and a stable abode. I wrote that Habima had been "living" in Berlin, but she had rather been devoting most of her time to hike through Europe, with no concern at all for a domicile. "It is always being resolved and I prefer to sleep outdoors" she explained. Like Meyrink and Crawford she proved to be well versed in Oriental art and religion and had in Japan spent time with Zen-inspired people. Despite all this, she gave no impression of adhering to fuzzy new-age notions, but spoke spontaneously and unpretentiously about herself and her art. I have rarely come across such a person and given that Habima in her exhibition catalogues instead of writing, for example, Habima Fuchs (1977, CZ), lives and works in Berlin she writes Habima Fuchs (1977, CZ), lives and walks in Europe made me remember Apollinaire's meeting with another wanderer.

Newly arrived Prague the French poet felt somewhat lost, stopped a passerby and asked him if he could recommend some of the city's attractions. The man replied in excellent French that he also was a stranger in town, but he knew Prague well since before and if Apollinaire did not mind him doing so he would be pleased to accompany him during a day´s walk through the city. Since he seemed to be a serious man Apollinaire accepted his kind offer.

While walking by his side, Apollinaire discreetly scrutinized his companion´s attire. He was wearing a long coat lined with otter skin and had tight trousers, which revealed a pair of unusually muscular calves. Like "German professors" he wore slouch hat. The man´s gait was unusually quiet and smooth, "as someone who is not becoming tired by not knowing his goal“. Suddenly, the man, who could have been in his sixties but nevertheless had a youthful appearance, stopped and pointed to the facades that surrounded them:

- Excuse me, Sir, 'he said. But please consider those ancient houses. How they have retained the symbols that once distinguished them, before street numbers were applied in this town. There is the Virgin's house and over there the Eagle's, which now is a gentleman's residence.

Apollinaire looked at the gateway to the Virgin's house over which a date was engraved. His companion read it aloud and then seemed to become lost in his own thoughts:

- 1721. Where was I when ...? Well, on June the 22nd I arrived at the gates of Munich.

While listening to him Apollinaire became concerned. Had he encountered a madman? The man told him how he had got arrested by Munich´s city guards and taken to the "inquisitors", who nevertheless had freed him from the police. Apollinaire smiled mischievously:

- You were certainly very young at the time. Very young! Not true?

His companion seemed not to notice the irony in the remark and responded with an unperturbed tone of voice:

- Yes, almost two centuries younger than now. But apart from my dress, I looked the same. Incidentally, it was far from my first visit to Munich, I had been there in 1334.

Then he witnessed a procession headed by a Jew equipped with donkey ears and an iron mask, on which a devil's face had been painted. The Jew was hanged and beside him a dog. The man stated:

- I do not like animals and therefore I don´t think it is proper that they should be treated like human beings.

Apollinaire realized who the man was and wondered:

- You´re a Jew, aren´t you?

- Yes, I am "The Wandering Jew". You guessed right. The Eternal Jew - it is in any case, what the Germans call me. My name is Isaac Laquedem.

- So, it was you who were in Paris last year, in April if I´m not mistaken? And for sure it was you who wrote your name in chalk on a wall in London. One day, I read it from the second floor of an omnibus. However, is your name not Ahasverus?

- Oh my God! All of these names! Sure, it's one of the many names they have gifted me with during all those years. I have received many more than that one.

The Wandering Jew began to enumerate names he had been given and places he had visited. Suddenly he stopped again and looked at the surroundings. Apollinaire realized that Prague was some kind of mirror for Isaac - The Eternal Jew. A city that constantly changes, which carry tracks and wounds of the passing time, still it remains the same, forever.

- Look at the church over there, muttered Isaac. It contains the remains of the astronomer Tycho Brahe; Jan Huss used to preach there and its walls carry the marks from both the Thirty Years´ and the Seven Years' Wars.

Though Apollinaire was more interested in Isaac Laquedem.

- I thought you did not exist. It seemed to me as if the legend about you just symbolized your wandering people. I appreciate you Jews and find it very unfortunate that you are treated so badly ... So, by the way, you drove away Jesus from your door?

- Yes, that's right. But, please be so kind not to talk about that

Isaac explained how he had been accustomed to wander without rest, without sleep. No longer did he consider his eternal life to be a nuisance. He had received a mission from God, a meaning with his life. There are few who have been blessed with such a treat. Through the millennia, he had walked back and forth over the earth. Every day he learned something new. At the day of the Last Judgment Day, he would report about his insights and experiences. What an honor! What a delight! To constantly see, hear and experience. At first he he had been tormented by his sins, their curse had weighed heavily upon him, but now he considered his eternal life to be a blessing. It was only fools who believed that he was tormented by it

- Even my loves do not last longer than a moment, compared to my eternal existence. No one can follow me through time. Come on! Laugh and stop fearing your future and death. It's time for dinner, walks generate an appetite. I am a glutton.

Full-bodied beer, goulash and gypsy music made Apollinaire and his new acquaintance feeling good.

- Vive la France! exclaimed Isaac Laquedem.

The night turned out to be orgiastic. Isaac took his French friend to frivolous ladies and Apollinaire's story degenerates into the vulgar pornography he is known for. At dawn they lurched out from a brothel. Isaac had paid the bill and Apollinaire noted:

- You really live the life.

- Sure I do. It´s divine. I feel like Wotan. Never being bored. But, now I have to continue. I've had enough of Prague and you are falling asleep. Go to bed. I never sleep. Adieu!

- Farewell. Wandering Jew. You lucky, erratic traveler! Your optimism is infinite; it's only crazy people who believe you are skinny fellow, haunted by anxiety.

- You´re so right and I have Jesus to thank for it all. He disowned me, made me different, inhuman and thus I learned the value of life.

Isaac walked on, but collapsed further up the street, roaring like a wounded animal. Apollinaire rushed up to him and unbuttoned his shirt. Isaac thanked him:

- Thank you. Time is ripe. A terrible force hit me. My life is over for now, but The Powers will soon provide me with a new one.

For a moment he looked worried and murmured:

- Oj, oj! "which in Hebrew means ´unfortunately´ ".

While police officers and "barely dressed men without hats and girls in starched, white dressing gowns" lifted up the dying Isaac and carried him away, Apollinaire was left standing alone, looking after them. An old Jew opened a door, looked at Apollinaire and muttered in German:

- It was a Jew. They will all die.

Then he unbuttoned his own coat and tore his shirt to pieces.

Magic Prague lives on, maybe not so much in the world of literature, but in the tourist industry and new media. For example, occasionally I read Italian comics, mostly because my scanty knowledge of the language is not quite enough for devouring novels. I generally read Dylan Dog or Dampyr. The latter takes place in the present, but within a mysterious reality where the past changes existence into a concoction of myths and legends.

Prague´s enigmatic city landscape is central to the mythology conjured in Dampyr. In Prague lives Caleb Lost, a pale man with an apparently phlegmatic and cool character. In fact, he is an amesha. Ameshas are benevolent, immortal spirits that Ahura Mazda, supreme god of the Zoroastrian religion, makes use of to communicate with his creation. Caleb lead the ameshas´ struggle against the hostile powers of darkness, His headquarters is in The Theatre of Lost Steps, which only specially invited persons can find at its location by the Verlorene Gasse, The Lost Alley, in Prague's Staré Město, Old City.

The authors of Dampyr, Mauro Boselli and Maurizio Colombo, base every issue of the magazine series on a thorough study of legends, horror stories and mythology. Their stories are set in all ages, all over the world, but Prague is often at the center and the Golem occasionally pops while the main protagonist Harlan Draka and his peculiar friends are chasing monsters and demons in the city's alleys. During their missions they can count upon the assistance of Nicholas, a fallen angel who moves around among the pubs and taverns of Prague. Nicholas is a kind of undercover agent who officially works for Nergal, the leader of the dark powers. Nicholas has a thorough knowledge of Prague's secrets and together with his mistress, Matylda Prusova, he was by Caleb´s side fighting the Nazi invaders as members of the Czech resistance.

Dampyr is filled with literary allusions and in the various Prague episodes a host of authors, artists and composers pops up, like Casanova, Jaroslav Seifert, Dvorak, Smetana, Jaroslav Hašek, Meyrink, Mozart, Kafka, Rabbi Loew, Tycho Brahe, Egon Kisch, Rilke, Wallenstein and Jan Neruda, along with mythical creatures like the Golem, Karkonoš, Rusalka and Libuše, or human monsters like Richard Heydrich. The illustrations are detailed and evocative. Oddly enough does Dampyr, like so many other Prague depictions present the city as co-actor in the stories and the same thing can be said about some computer games that now appear.

One example is the historic environment so central to the very popular Canadian Assassin's Creed, which since its introduction in March 2013 has sold over 55 million copies worldwide. Like Dampyr this computer game evolves around two ancient sects, while their struggle rage in different times and different countries. In Assassin's Creed the opposed forces are the Knights Templar and the Assassins. Contemporary figures, such as the bartender Desmond Miles, mix with mythical, historical figures like the assassin Altaïr Ibn-La'Ahad. The origin for the whole concept may be found in a novel by the Slovenian writer Vladimir Bartol, Alamut written in 1938

It is thus hardly surprising that the Magic Prague, with its alchemists and Golem has appeared in Assassin's Creed, but only as a single-player game on Facebook. The so-called Divine Science Story Pack took place in Prague around the turn of the seventeenth and sixteenth centuries, but it was apparently not a success. It was closed down and was not developed any further.

However, that does not say anything about the survival of Magic Prague. Even if the old ghetto was demolished by the beginning of last century, the streets have been widened and tourist hordes have poured in during the last decades; old, mysterious Prague lives on. Many of the ancient houses, castles, churches, tombs and synagogues are still there, underground run unknown passages, while myths and legends continue their lives in novels, films and new media. The city breathes and lives, its soul seeps into the minds of inhabitants and visitors alike. Like Rome, Prague is a Città Eterna, an Eternal City.

In these days of mindless jingoism, it may be opportune to recall the joy of loving a specific place, without despising other people and their places. Vitĕzslav Nezval, one of Prague's many poets, wrote about his beloved city:

I’ve no illusions about nations which rule the world, or about

foreign settlements

I don’t regard the people whose language I speak as either better

or worse than those of other countries

I’m linked with the fate of the world’s disasters and only have a

little freedom to live or die

Though

To future generations I bequeath my experience and a long sigh

For the unfinished song which wakes me, which lulls me to sleep

Remember me

That I lived and walked about Prague

That I learned to love her in a way no one loved her before

Apollinaire, Guillaume (2010) La Légende du Juif errant suivi de Le Passant de Prague. Paris: Interférences. Cohn, Norman (1967) Warrant for Genocide: The Myth of the Jewish World Conspiracy and the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. Crawford, F. Marion (2008) The Witch of Prague & Other Stories. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. Demetz, Peter (1998) Prague in Black and Gold: The History of a City. London: Penguin Books. Kafka, Franz (1958) Description of a Struggle and Other Stories. New York: Schocken Books. Kafka, Franz (2011) Letters to Friends, Family and Editors. Richmond, Surrey: Oneworld Classics. Meyrink, Gustav (1994) The Opal (and other stories). Sawtry, Cambridgeshire: Dedalus/Ariadne. Meyrink, Gustav (1976) The Golem. New York: Dover Publications. Mitchell, Mike (2008). Vivo. The Life of Gustav Meyrink. Sawtry, Cambridgeshire: Dedalus/Ariadne. Nezval, Vitezslav (2009) Prague with Fingers of Rain.Translated by Ewald Osers. Tarset, Northumberland: Bloodaxe Books. Pfeiffer, Ernst (ed.) (2008) Rilke and Andreas-Salomé: A Love Story in Letters. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. Topor, Roland (1976) The Tenant. New York: Bantam Books. Soukup, Vladimír (1994) Prag (DK Eyewitness Travel Guide). London: Dorling Kindersley.