SRBSKO: Europe's centre and a memory

Any memory is an interpretation, a rectification. Our existence, politics, world history are constructed by our own and others' memories, which find themselves in state of constant change. Not even our thinking is persistent. Things, like the nature, buildings and books are somewhat more persistent, though even they are shaped by memories, our constantly changing interpretations of them.

I recently learned this while reading a book by Matt Masuda, The Memory of the Modern. Through examples from French history the author analyses and interprets the importance of monuments through the resurrection, demolition and reconstruction of the Vendôme Column in Paris. He also investigates how numbers were used on the Paris stock exchange and then impacted the economy as a science. How French linguistics and telegraphy converted words into signs. How human bodies are shaped by memories and events and how this was reflected in French anthropology and Henri Bergson's philosophy. How witness testimonies were evaluated, explored and interpreted by French law. How criminals were identified by statistics, charts and photographs. How French imperialism, prosecution and deportations were influenced by exotic views of “the other”, cultivated by authors and philosophers. How the conservation of events was transformed into entertainment through automates and cinema and finally how dance and music combine influences from different cultural contexts and become interpreted and reformulated by authors and musicians. Masuda's common denominator is to demonstrate how memories both shape the human mind, our environment, history and future. How they give rise to different trends in science, social life and politics. An ever-ongoing dynamic; influential, fluid and changeable just like our own personal memories.

While reading Matsuda I remembered how many of my memories were related to a place, a building and various stories I read or heard. How an edifice encloses a variety of ideas, thoughts and performances, while being in a state of constant flux. How a visit to any place is influenced by the unique memories, associations and meanings it carries and how they shape our memory of our visit

By mid-March last year, I arrived by train to Srbsko, a village a few miles south of Prague with a name that seemed to be taken from a Tintin adventure. Srb is apparently “Serb” in the Czech language, but why an insignificant place like that would be named “Serbia”, remains a mystery to me. It was twilight, and Srbsko seemed to rest in moisture and dreariness, withholding memories of everyday communism. Apparently, I was the only guest at the hotel, which was opposite the station, though on the other side of a river with viscous, brownish water.

The oblong room was small but warm and provided with the essentials for a hotel stay. Unfortunately the restaurant was closed. I went out into the evening mist searching for a place to eat, but the two taverns were closed due to off-season. I had to be content with sitting in a corner with a pint of lager and a kloábasa sausage with rye bread and mustard, while a group of villagers curiously watched me from a table at the opposite end of the room. Feeling like the odd stranger I was, I was nevertheless pleased with my loneliness.

The next morning I went up early and was in the empty restaurant welcomed by a laid out, sumptuous breakfast, a nutritional supplement that lasted all day long. In spite of the drizzle I decided against taking the train and walked on foot to immerse myself in the subtle atmosphere of unrestrained melancholy. During my hour-long walk I did not meet any cars and no people. The landscape along the abandoned road was varied and sometimes even beautiful, with river and fields on one side and woods and rocks on the other.

Settlements were not dense. Occasionally, I passed a deserted small factory or forsaken garage surrounded by rusty car wrecks. Especially fascinating was a tower crowned by black, rotting woodwork. It did not seem to be very old, perhaps it had been raised by some eccentric industrialist a hundred years ago. Now it looked threatening, a likely home for bats, or perhaps a miserable vampire whose presumed presence was a source of exciting horror for the children of the surrounding countryside.

Even the telephone wires that followed the road were imbued with a sinister character, which suggested a not entirely forgotten communism, characterized by secretive oppression and inferior services.

The March winter still kept the landscape in its grip, though a blooming twig lit up the scrubby forest and told me that spring after all was on its way, in the midst of an almost compact greyness.

If the woods were rather sad and forsaken, the cliffs were all the more exciting and colourful. In some places they glittered in red, blue and taupe, while on other surfaces they were covered by meandering patterns formed by ingrained pebbles.

I reached my goal - Hrad Karlštejn, a magnificent, medieval fortress high upon a rock above an old trading town, now transformed into a tourist trap. My first sighting of this fabulous castle, as dreamlike as a Hollywood backdrop, was from a cemetery.

At this early, humid morning there was no trace of tourists, other than barred souvenir shops. With rising expectation, I walked up towards the hovering castle. Of course, I came to think of Kafka´s The Castle and its errant land surveyor - if he really was a land surveyor? Maybe it was a lie of his? – while he went astray in an unfriendly village, in vain seeking access to an impenetrable castle, which threateningly brooded above by the villagers miserable and incomprehensible lives.

Of course, I had read bits and pieces about Karlstein before I went there and since I had seen the castle on pictures I associated it with Kafka's novel. However, in spite of my earnest attempts to discover a connection I did not find much that united Kafka with Karlstein, only a note in a letter to his sister Ottla, which nevertheless was vintage Kafka. From a rainy Prague he wrote in May 1916 that he did not want to accompany his sister on a weekend trip to Karlstein. As a reason for his deviation Kafka stated that he did not know who Ottla, besides himself, had intended to bring with her to Karlstein and that he did not want to bring the misery he felt in in Prague with him on a pleasure trip: mein Unbehagen in Prag gerade groß genug ist, um es nicht noch in Bewegung bringen zu wollen “my discomfort in Prague is big enough for me not wanting to bring it in motion."

The fact that Kafka did not travel to Karlstein with his sister is no proof that he did not visit the castle, or that he was not inspired by it. After extensive restoration work had been completed in 1899, the castle and its trading town became a popular destination for the citizens of Prague, especially since they could easily arrive there by rail. Like most medieval sites the castle had had the time to accumulate a significant amount of legends, often of a quite creepy character. Beneath it were deep, damp dungeons, and during the restoration work a treasure of precious jewellery had been found behind a wall.

Kafka's friend and chronicler, Max Brod, denied that Kafka ever read horror stories and Gothic novels, like those by Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley, Matthew Lewis, Charles Maturin and Bram Stoker, not to mention similar stories, which at the time was mass-produced as dime novels. This is somewhat surprising since Kafka´s writing is lavished with horror-romantic elements. In any case, he read and appreciated E.T.A. Hoffman, Heinrich von Kleist and, not the least Fyodor Dostoevsky, all of whom were consumers of gothic horror and whose works don´t lack resemblances to the genre. Perhaps Max Brod, who had a tendency to gild his author friend, liked to avoid that the afterlife perceived Kafka as an avid reader of the kind of literature that some snobbish, literary circles like to discredit.

Kafka´s The Castle appears to have quite a lot in common with German Schauergeschichte from the Romantic period, in which external events are reflected by the inner worlds of narrators who tell horrific stories, like the slowly dying Franz Kafka who writes about the alienated land surveyor K's experiences in a nightmarish world that reminds us of our own, in spite of being remote from it. The fact that Kafka´s protagonist is a loner designated by a single letter was a common trait of gothic horror literature ever since Friedrich Schiller in 1787 wrote his Der Geisterseher - Aus den Papieren des Grafen von O**, The Ghost-Seer - From Count von 0 ** s Writings.

I wonder if Kafka had not heard of Francis Marion Crawford's horror story The Witch of Prague, published in English in 1891, but not translated into German until 1929. That Kafka might have heard of this once popular novel was not only due to the fact that the events take place in Prague, but that the main character is called Israel Kafka. More likely is it that Kakfka maybe had read another gothic horror novel, which I found in facsimile online - Drahomira mit dem Schlangenringe: oder, die nächtlichen Wanderer in the Schreckensgefängnissen von Karlstein in Prague: Eine Schauergeschichte aus Böhmens Grauer Vorzeit von Ludwig Dellarosa, 1842. The title is undoubtedly enticing - "Drahomira with the Snake Ring: or the Night Wanderer in Karlstein's Horror Dungeons in Prague: A Horror Story from Bohemia´s Grey Past by Ludwig Dellarosa, 1842."

However, I found the German fraktur text irritating and gave up after reading almost half of the book online. After a detailed description of Karlstein's ruined castle, the novel told of a young Bohemian beauty called Drahomira, who in a medieval Bohemian deep forest met a witch who gave her a ring in the form of a snake with emerald eyes. If Drahomira whispered a wish to the ring, and if it would be granted, the snake eyes would glow and sparkle, but if the future had something bad in waiting for her, the shine of the emerald would be matted.

I never came so far in the hard-to-read novel that I could find the connection between Drahomira and Karlstein. Ludwig Dellarosa was one of the many pseudonyms used by an Austrian public servant and the theatre director whose real name was Josef Alois Gleich (1772-1841). He wrote no less than over a hundred novels and two hundred and fifty plays, though he died poor and his numerous books were soon forgotten.

As with all reading, new paths opened up leading into fascinating worlds. Drahomíra? She was born either 877 or 890 and died 935. After marrying Vratislav I, Drahomíra became Duchess of Bohemia and when her husband suddenly died she inherited the Duchy until her son Wenceslas came of age. In Czech, the son of Drahomira is called Dobrý Král Václav, The Good King Wenceslas, and is revered as the founding father of the Czech Nation.

Drahomíra was born as a princess of the Slavic tribe Hevelli and not a Christian. Instead of the Christian God she worshipped Rod, Creator of the Universe. Rod had two aspects, Belobog, The White God and the Chernobog, the Black God. Rod was thus neither evil nor good, but did in his being include everything, which meant that evil could sometimes benefit the good, and the other way around, something that Drahomíra apparently held to be true.

Even if she was baptized at her marriage Drahomíra never abandoned the faith of her ancestors. Her mother-in-law, Ludmila, on the other hand, was a pious Christian lady. Supported by Germanic monks and clerics Ludmila brought up the little Wenceslas in the true Latin faith. Drahomíra became furious when the increasingly powerful German clergy deprived her of the custody of little Wenceslas. As a comfort, she took care of her younger son, Boleslav, who, according to plans, would never become a Bohemian ruler.

With some reason Drahomíra assumed that her mother-in-law was using Bavarian priests in an attempt to brainwash little Wenceslas and thus circumscribe Drahomíra's greater influence over the fate of the Duchy, linking Bohemia closer to the Germanic and Christian Saxons. Drahomíra's increasing aggressions made Ludmila fear for her life and she decided to seek refuge in the Bavarian bishop´s residence in Regensburg. On her way Ludmila there resided for a while in the castle of Tetín, south of Prague.

When Drahomíra learned about the whereabouts of her mother-in-law's, she summoned two "Norsemen", the Vikings Tunna and Gommon, and sent them after Ludmila with orders to kill her. Drahomíra had been foretold that, for the sake of her own and her sons´ wellbeing, she had to have Ludmila killed, though if blood was spilled by her murder God would punish Drahomíra by letting one of her sons bleed to death as well.

Tunna and Gommon managed to enter Ludmila's bedroom at the Tetín castle. When she saw the intruders enter through the window Ludmila rushed to the altar to seek God's protection, but was overpowered and strangled to death. However, when the lifeless Ludmila fell to the floor her forehead hit the edge of the altar and bloodied it, an extremely evil-boding sign meaning that one of Drahomíra's sons eventually would suffer a violent death.

Wenceslas accepted with apparent calm the announcement of his beloved grandmother's death, but as soon as he came of age and finally ruled over the Bohemian Duchy he exiled his mother and sought by the German Duke of Saxony, Henry the Fowler, support and protection against the mostly pagan Magyars, who were threatening Bohemia´s southern border. Henry the Fowler ensured that Bohemia ended up within the sphere of Roman Catholicism. As a sign that Bohemians now were following the Latin rite, and as a bond between Germans and Slavs, Henry the Fowler bestowed Prague the skeleton hand of the Sicilian saint St. Vitus. Over the Holy Hand Wenceslas built the church that would eventually be transformed into Katedrála Svatého Víta, Prague's magnificent cathedral. It is possible that Henry the Fowler chose a relic of St. Vitus as a gift to Bohemia's Czechs since the Saint´s Czech name Svatého Víta reminded of Svetovid, a revered Slavic god who ruled over war, fertility and abundance.

When Wenceslas was assassinated by his younger brother Boleslav, acting at the behest the two brothers own mother Drahomíra, his murderer almost immediately declared that Wenceslas had been a saint and he was soon transformed into the divine guardian of Bohemia and eventually became the Czech Republic's patron saint. Protests during the Prague Spring in 1968 and the Velvet Revolution in 1989 were centred around Wenceslas´s statue in in the Vaclav Square of Prague.

Wencesla´s skull is still kept in St.Vitus Cathedral and is every year on the 27th September during solemn procession brought to Stará Boleslav two miles north of Prague, the place where Wenceslas was murdered by his brother. On the day of the saint's death on the 28th September a mass is celebrated in the church that after a few hundred years after the murder was built on top of the wooden church outside of which Wenceslas had been murdered.

Despite his evil deed Boleslav´s posthumous reputation is not at all bad among the Czechs. During his long reign, Boleslav became an impressive law maker who furthermore tried to bring order in the Bohemian finances. Boleslav I was a minion to the mighty Saxons, though under their authority he managed to create a strong army, which he used defeat the threatening Magyars. Even if Boleslav had ordered the murder of his brother, he nevertheless benefitted from his sainthood and also used his Catholic grandmother Ludmila, who was canonized already in 925, ten years before the murder of Wenceslas, to strengthen the position of the Czechs against the Saxons. Boleslav made Prague the centre of a bishopry, built a system of garrisons along the borders and welcomed merchants from all countries, not the least Spanish Jews and Moors.

Perhaps as part of this policy, Boleslav demonstrated great and public remorse for the murder of his saintly brother. According to legend, Wenceslas was stabbed to death while Boleslav and his court celebrated the day of the curative saints Cosmas and Damian. At the same moment as Wenceslas gave up his breath in front of a barred church gate, Boleslav's wife gave birth to a son. The assassin brother considered the birth of his son to be a sign from God and gave his firstborn the strange name of Strachkvas, Dreadful Feast. Strachkvas was vowed to God, became a monk and died as bishop of Prague.

Apparently, Drahomíra lived until her death at Boleslav´s castle in Prague. However, legends tell another story, here told by an English, illustrated "folk book" from 1729:

Drahomira Queen of Bohemia was an implacable Enemy to the Christians, and caused many of them to be slain; but as she happened to pass over a place, where the Bones of some godly Ministers (who had been martyred) lay unburied, the Earth opened its mouth, and swallowed her up alive, together with the Chariot wherein she was, and all that were in it: which place is to be seen before the Castle of Prague to this day.

What is the connection between Drahomíra and Karlstein's castle? Probably non-existent, except that both the brutal lady and the impressive castle have been linked to several horror stories and the fact that the ruins of the castle Tetín, where Ludmila was murdered, is less than a mile from Karlstein and once was its nearest castle.

Directly connected to Karlstein's castle is however the story of Kateřina Bechyňová, who in 1534 was sentenced to death for 14 murders and locked into Prague's Gunpowder Tower, where she died of starvation. Of course, she and her victims still haunt in Karlstein's dungeons.

Kateřina was married to the margrave Jan Bechyně of Lažany, who due to his responsibilities was forced to spend most of his time in Prague and consequently handed over the care for Karlstein to his wife Kateřina, who was rumoured be mentally unstable. She was an extremely severe mistress of the house and any small mistake committed by her servants was severely punished. She allegedly went so far that several of them were tortured in her presence, some died, while others were crippled for life.

Meanwhile, her husband came in violent conflict with Vaclav Hajek, the Dean of the Chapter of Karlstein. Initially, Jan Bechyně was not accused of any misconduct connected with the care of the castle, something he would actually have been nowledgeable about, since he occasionally stayed there for longer periods. When the disagreement between Jan Bechyně and Vaclav Hajek worsened, Hajek who eventually became a well-known author, presented his complaints to the royal authorities under Ferdinand I, Bohemian satrap under the German-Roman emperor Charles V. The imperial judges considered that the reports of abuse at Karlstein were the most engraving of Hajek´s complaints about Jan Bechyně.

Vaclav Hajek had gathered testimonies from priests in the vicinity of the castle, who had told him how several of Kateřina´s servants had been tortured, or starved to death in Karlsteins dungeons. Jan Bechyně countered the accusations by suing Vaclav Hajek for perjury. However, during the trail Bechyně was proved wrong when several witnesses confirmed that several unexplained deaths had occurred. Bechyně escaped by incriminating his wife, who immediately was arrested for the murders.

At first, terrified witnesses assured that their housewife was a "gentle and friendly lady". However, a wealthy citizen of Prague finally testified that one of his relatives had been tortured in the presence of Kateřina. His testimony made Kateřina extremely upset. Her insecure and confused behaviour made the court recall several of the former witnesses, who now changed their declarations, accusing Kateřina of cruelty and unbridled sadism. At last Kateřina acknowledged that she had caused fourteen deaths, although the court reckoned that at least thirty of the Castle´s servants had disappeared without leaving a trace. Kateřina Bechyňová was sentenced to death by being immured without food or water.

The harsh verdict had no consequences whatsoever for Jan Bechyně, who shortly after his wife´s death was appointed as "provincial scribe", a higher position than the one he had previously enjoyed. The unusual punishment of such an exalted aristocrat as Kateřina Bechyňová received a lot of attention and when her judge, Vojtěch of Pernštejn, unexpectedly died in March 1534, just two days after Kateřina, it was rumoured that she had brought him with her down to Hell.

Karlstein's castle was built between 1348 and 1368, during a time of cultural and economic peak for Bohemia. This was a period of European history that was entirely different from the notion that nowadays use to be expressed by fervent nationalist. As a matter of fact, the concept of “a nation” did not exist, the European states were dynastic and territorial, not national.

Perhaps a small didactic excursion could be in place - there are two national concepts. One is an inheritance from a 19th century German debate about ethnicity, language, culture and history. The other is linked to the concept of "citizenship" and originated during the French Revolution, when French nationality was considered to be shared by all French citizens, regardless of their ethnic background. The German concept, which legacy now plagues us all, arose as a reaction to French imperialism.

During the late Middle Ages, when Karl IV had Karlstein erected, the European reality was completely different from what it is now. Control and power was disputed and fought over by emerging dynasties – the Oldenburgs, Wittelsbachs, Valois, Tudors, Habsburgs, Vaasas and several others, which changed and redraw the boundaries of ever-changing states. One example was the House of Luxembourg.

When the last heir to the Přemyslid dynasty of Bohemia, founded 935 by the above mentioned brother slayer Boleslav I, was murdered in 1306, the House of Habsburg tried to usurp control over Bohemia. A coalition of clergy, nobility and citizens from Prague feared that the House of Habsburg would threaten their wealth and wellbeing and thus sought protection from the German-Roman Emperor Henrik VII of Luxembourg, whose son John married a princess from the House of Přemyslid.

John, who spoke only French and Latin, intended to unite Bohemia and Poland against the House of Habsburg, which ruled over several widely spread European territories and the House of Wessex, which ruled over England. The fiercest battle grounds where in France, where John fought with his Slavonic troops in what eventually became known as the Hundred Years´ War, in which the House of Plantagenet, the House of Wessex and the House of Valois fought over the succession to the French throne. Part of this bloody contest was the battle of Crécy.

Joan, who had been blind for ten years, led his troops in the bloody battle. Jean Froissart tells us in his Chronicle:

… the king said a very brave thing to his knights: “My lords you are my men, my friends and my companions-in-arms. Today I have a special request to make of you. Take me far enough forward for me to strike a blow with my sword.” […] In order to acquit themselves well and not lose the King in the press, they tied all their horses together by the bridles, set their king in front so he might fulfil his wish, and rode towards the enemy. [...] he came so close to the enemy that he was able to use his sword several times and fought most bravely, as did the knights with him. They advanced so far forward that they all remained on the field, not one escaping alive. They were found the next day lying around their leader, their horses still tied to each other.

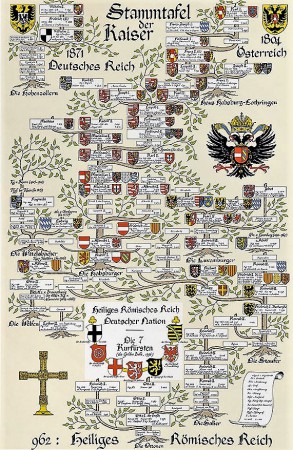

John´s son Charles also participated in the battle of Crécy, but otherwise he lived with his mother in Prague. After his father's death, Charles was elected Emperor over the German-Roman Empire. This Empire may be described as some kind of European federation with a common parliament. Bishops, dukes and kings chose an emperor who would have the highest power over them all. When it was at its greatest, the German-Roman Empire included present Germany, Austria, Slovenia, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, as well as the northern and south-eastern parts of Poland, eastern and southern parts of France and northern Italy.

.jpg)

As a newly elected Emperor of this federation, Charles IV wanted to create a constitutional position for himself and his future Bohemian descendants. They would be foremost among all the princely electors of the German-Roman Empire, and from then on the Emperor would be chosen from members of the House of Luxembourg, which more firmly than ever before would unite "a federation of princely states under the leadership of the Emperor." This and a variety of other imperial laws were established in the so-called Golden Bull from 1356.

Charles IV was a powerful and energetic ruler who spoke a multitude of languages and occasionally travelled to the different corners of his vast empire, for example did he for long periods reside in Nuremberg and northern Italy. A sign that the rulers in those days did not consider themselves circumscribed by any national interests or borders. It was their own, personal power they cared about. This was not the least proven by Charles marriages, he did not at all care about his wives ethnicity, what counted was the political gains he could have by using his marriage bonds. Charles IV married four times, three of his wives died during his reign. His wives were Blanka of Valois from France, Anna of Palatinate from Bavaria, Anna of Schweidnitz from Hungary and Elisabeth of Pomerania, the last survived her husband.

.jpg)

In Prague, Charles IV founded the first university north of the Alps and east of the Rhine. It provided his imperial government with skilled administrators, attracted learned men from all over Europe and gave an intellectual lustre to the Emperor and his court. Magnificent buildings were erected throughout Charles´s empire and he embellished Prague. Several of the mighty edifices remain, among them his master builder Peter Parler´s magnus opus - the mighty St. Vitus Cathedral and legendary Charles Bridge in Prague.

Particular care was also provided to the castle of Karlstein, which was going to be the home of Karl IV and served him as such during the last ten years of his life. In Karlstein's Chapel of the Holy Cross he kept the regalia of the German-Roman Empire. In there, Charles could in contemplative loneliness admire the imperial crown from the 10th century, with which he in Rome, by the Pope himself, had been crowned Emperor in 1355.

Among the regalia was the sword of Charlemagne, the holy lance brought back from the First Crusade, the Imperial Sword from the 12th century, the Imperial Orb from the 13th century, the Norman Coronation Cloak from Palermo, the Imperial Cross with pieces of the cross of Christ and a variety of other relics, including a tooth from John the Baptist and several other treasures that now can be admired in Vienna, since the House of Habsburg brought them there in 1796 after the treasures for centuries had been kept in Nuremberg.

It was Emperor Sigismund who brought the regalia to Nuremberg after being elected Emperor in 1423. Sigismund was the son of Charles IV's fourth wife and when he was elected Emperor, it was in protest against the reigning Emperor Wenceslas IV, son of Charles IV's third wife. Wenceslas IV had unfortunately ended up in a conflict with the Pope and the Catholics. Sigismund, however, was a crusader who was fighting hard against the Turks and therefore was highly esteemed by The Holy See in Rome.

Bohemia's splendour and wealth under Charles IV benefited from the disasters that plagued Western and Southern Europe, which after devastating wars had suffered the terrible Black Death, killing between 30 and 70 percent of Europe's population between 1347 and 1351, depending on the areas affected. Strangely, Prague, as well as large parts of Bohemia and Poland had been saved from the pestilence. Good harvests and mounting prestige increased the power of Charles IV and it appeared as if his reign had been blessed by God.

In the midst of all this well-being Karlstein's castle was completed in 1368 and became the centre of a resurrected, progressive Europe. A splendour that soon would be tarnished by Charles IV's son Wenceslas IV, who was challenged by the almost impossible task to keep his sprawling empire together, a mounting chaos that soon would erupt in the blood-drenched religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Those wars originated in Prague where Jan Hus´s provocative sermons against the German clergy of Bohemia and Pope John XXIII's indulgence trade led to the excommunication of Hus and his Czech followers. Hus protested by allowing his congregation to taste the wine during mass. Finally, Hus was sentenced to death and burned alive in the square of the German town Konstanz, where he had come to defend his cause.

Disaster followed after Sigismund, supported by the Pope and the Catholic nobility, had wrenched the power from his brother Wenceslas. Bohemian nobles refused to swear allegiance to Sigismund and a general resurrection began. A violent civil war raged between 1419 and 1436. The radical Hussites were led by the one-eyed and never-defeated Jan Žižka, who routed Sigismund's crusaders in one battle after the other. After Žižka's death in the plague of 1424, the Hussites became fractured and rulers from other areas entered the fighting in pursuit of the spoils after an eventual victory.

Among them was the Pole Sigismund Korybut, who initially fought on Žižka's side, but when he later saw where the wind was turning joined the Catholic crusaders. While supporting the Hussite cause he did in 1422 besiege Karlstein. The great castle, high on its cliff, with an inexhaustible deep well and an abundant storage of cereals and salted meat, appeared at first to be impregnable. However, Sigismund Korybut succeeded in defeating the defenders through biological warfare. Catapults throw corpses above the walls, along with 2,000 chariot loads of manure. Disease soon spread among the castle´s defenders and they were forced to give up.

In a drizzle I walked between the closed souvenir shops along the steep road up to the castle. Even its courtyard was empty and abandoned, though by the ticket booth I could pay for a guided tour, the only opportunity to visit Karlstein's castle and soon I walked through the big halls in the company of an elderly lady and a guide who in German told us about the different rooms.

The castle was sparsely furnished and much of the furniture and decorations were copies of the original fittings. Possibly was Karl IV's bed the same as the one he had used and he probably also made use of the prayer stool in front of a wooden statue of Virgin Mary, which along with a seemingly freezing Christ, were the only decorations in his bedroom.

Everything must have been more sumptuous during the Emperor´s time at the castle, something an exhibition of his table decorations testified about. After the guided tour, I was free to walk alone around the castle's exteriors, from which I occasionally had a magnificent view of the surrounding landscape.

After a couple of hours at the castle, I crossed a bridge to the other side of the river, from where I planned to take the train back to Srbsko, but I found that it would take a few hours before its arrival. So I went into a tavern and took a pilsner, watching the other guests, who sat in the afternoon grey room quietly conversing over their beer glasses. I decided to walk back to Srbsko along the other river bank. Even if I had seen that it on some places consisted of steep rocky walls, I suspected that there must be a path above the precipices.

I followed the river and soon the road became a narrow path. The rain had ceased and when the sun broke through under a heavy cloud cover, the landscape obtained a mild, golden appearance. I passed some empty houses and a large factory plant that seemed to be abandoned.

The path disappeared, but I managed to get under the railroad through a tunnel and after tearing me through a bushy glade with blackberries and rotting twigs, I came across a strange place that seemed to have been some kind of summer camp for youngsters. Several triangular wooden huts lay scattered in clumps in different places of the wood. In some of them beds and mattresses remained and some of the shelters appeared to have been burned by fire.

Finally, I found, a narrow, paved road leading up to a village, which seemed to be abandoned except a lot of hens that ran around freely everywhere. The road became steeper and finally reached a plateau with extensive fields.

Again, the road had disappeared and I had to climb over a few cliffs until I reached the edge of a steep hill overlooking the river landscape. I had definitely reached the end of passable terrain and did not want to risk my life by free climbing. I had no other choice but to return to the other river bank going back through the terrain I had already traversed.

While I returned, I could in the distance see the towers of Karlstein's castle.

When I tired, but satisfied, in the dusk had returned to Sbrsko, I wondered about what I had seen and experienced during the day. At different levels it had been a journey through time and space, but it was mostly a memory. As Matt Masuda pointed out, memories shape our lives and perceptions, the past, the present and the future. My time in Sbrsko and Karlstein was now a memory, a moment on earth. Salvatore Quasimodo's wrote:

Ognuno sta solo sur cuor della terra

trafitto da un raggio di sole:

Ed è subito sera.

Everyone is alone on the heart of the earth

pierced by a ray of sun:

And suddenly it's evening.

Agnew, Hugh (2004) The Czechs and the Lands of the Bohemian Crown. Stanford: Hoower Press. Bridgwater, Patrick (2003) Kafka, Gothic and Fairytale. Leyden: Brill. Burton, Robert (2010) Wonderful prodigies of judgement and mercy, discovered in near hundred memorable histories (facsimile from A. Bettesworth and J. Batley, London 1729). Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale ECCO. Dellarosa, Ludwig (1842) Drahomira mit dem Schlangenringe: oder, die nächtlichen Wanderer in den Schreckensgefängnissen von Karlstein bei Prag: eine Schauergeschichte aus Böhmens grauer Vorzeit. Facsimile on line, Google Books. Froissart, Jean (1978) Chronicles. Aylesbury: Penguin Classics. Kafka, Franz (1975) Briefe an Ottla und die Familie. Frankfurt am Mein: S. Fischer. Matsuda, Matt K. (1996) The Memory of the Modern. Oxford: Oxford University Press.