THE SLEEPERS: Legends, movies and mental institutions

When I a few days ago indolently watched TV I ended with a rather insane science fiction movie called Pandorum. It was about how 60,000 people in 2174 had been induced to hyper sleep and sent off on a 123-year-long trip to a planet called Tanis, reckoned to be similar to Earth. Every two years two crew members were awakened to watch over their cargo of sleeping people, while their predecessors returned to hyper sleep. The movie became increasingly bizarre when it turned out that a supervillain through gene altering fluids, which he had introduced into some of the sleeper's oxygen supply had transformed them into degenerate, man-eating monsters.

Pandorum is one of several other science fiction films in which people have travelled in deep sleep, far away into unknown spheres of existence. It would suffice to mention 2001, Planet of the Apes and Alien as some of the better contributions to a genre with roots down deep in Antiquity.

In the Middle East there exist age-old traditions about how men have fallen asleep in a cave and been awakened hundreds of years later. One such legend gained a compelling influence during the 400's AD, perhaps in conjunction with the Council of Ephesus in 431 when Virgin Mary was recognized as worthy of veneration and cult throughout Christendom at the same as it was decided that all the temples destined for the cult of Roman emperors were to be destroyed.

Some five kilometres outside of Ephesus, not far from modern Izmir in Turkey, you may if you are lucky, since it is occasionally is sealed off by a fence, visit the Cave of the Seven Sleepers. Several Christians and Muslims believe in the miracle of the Seven Sleepers, especially since it is highlighted in the Qur´an. Since the Qur´an is not telling us where the miracle occurred, several caves are currently venerated as the place where the seven men fell asleep. The most visited cave is under a modern mosque just outside of Amman in Jordan. However, everything indicates that the cave outside Ephesus is the original site of the Christian worship of the Seven Sleepers.

The large cave below a hill called Panayirdag was already in the sixth century the goal of numerous pilgrimages. Between 1927 and 1928 the site was excavated and hundreds of graves from different time periods were found. They had been placed under mosaic and marble floors in various shrines erected at different times. In the seventh century a now vanished, large dome surmounted a mausoleum built on the hill slope. Several graves were from the fifth century and inscriptions in tombs and on the cave walls were referring to the Seven Sleepers. Such inscriptions are actually mentioned in the Qur´an.

The fascinating and for its time incomprehensibly well informed historian Edward Gibbon provides in his The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, written as early as in the 1770s, a comprehensive account of how the story of the Seven Sleepers was written down already fifty years after the event was said to have occurred, i.e. under Theodosius II's reign (408-450). Gibbon tells us how the legend spread throughout the Near East, how it reached the Arabs and Muhammad and soon ended up on the far away northern coasts of Germania, where Paul the Deacon (720-799) places the story, which by him has been turned into a different kind of miracle story, implying that the pagan peoples in the far North might one day become Christians as well:

In the farthest boundaries of Germany toward the west-north-west, on the shore of the ocean itself, a cave is seen under a projecting rock, where for an unknown time seven men repose wrapped in a long sleep, not only their bodies, but also their clothes being so uninjured, that from this fact alone, that they last without decay through the course of so many years, they are held in veneration among those ignorant and barbarous peoples. These then, so far as regards their dress, are perceived to be Romans. When a certain man stirred by cupidity, wanted to strip one of them, straightaway his arm withered, as is said, and his punishment so frightened the others that no one dared touch them further. The future will show for what useful purpose Divine Providence keeps them through so long a period. Perhaps those nations are to be saved some time by the preaching of these men, since they cannot be deemed to be other than Christians.

Paul the Deacon obviously did not know the legend in the form it had obtained within the former Roman Empire, though the bishop of Tours in the Loire Valley of France, knew it quite well and wrote it down two hundred years before Paul the Deacon. In his chronicle of Frankish history Gregory of Tours (538-594) tells the story of the Seven Sleeper in a way that basically is consistent with the version Jacobus Voragine in 1260 presented in his book The Golden Legend, a collection of legends that became one of Christendom's most popular books.

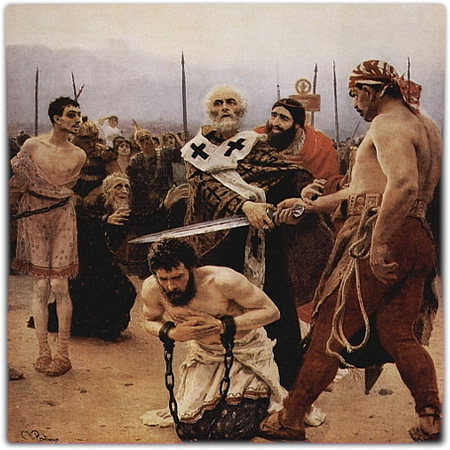

According to the legend, the Seven Sleepers were wealthy, young Christians who lived around the year 250 in Ephesus, their names were Maximian, Malchus, Marcianus, Dionysius, John, Serapyon and Constantine. In that year the Roman Emperor Decius had decreed that all Roman citizens who did not sacrifice for the emperor's wellbeing would be executed. The seven men gave away their possessions to the poor and withdrew to a cave under the mountain of Celion. When the emperor learned about this he ordered the cave to be sealed off by a stone wall while the young men were sound asleep inside, with the intention that they would die of hunger and thirst, after as Gregory of Tours wrote "devouring one another." The day after the erection of the wall, two men wrote down the immured men´s life story and stuck a parchment with it between the stone blocks.

Thirteen years after Emperor Theodosius II had come to power the wall in front of the sleepers cave was torn down, i.e. ten years before the Council of Ephesus. Here Voragine is poorly informed because he writes that it was 372 years after the men had been detained within the cave, in fact it was 180 years. The Qur´an states that "they stayed in their cave for three hundred years, and [some] add nine." It is interesting to note that the Qur´an use solar years, and not lunar years, which otherwise is customary in Islam. The Qur´an states that "some add nine" - 309 lunar years are actually equivalent to 300 solar years.

The wall in front of the cave entrance was torn down because some shepherds wanted to use the cave as a corral for their sheep and thus replaced the wall with a fence. The following morning brought the sunlight to the sleeping men and woke them up. They thought they had slept for just one night and sent Malchus down to Ephesus to buy bread and to check upon the current situation. He became surprised when he saw the newly erected fence outside the cave and a Christian cross above the city gate. When he tried to pay the bread with centuries-old coins, it rose quite a stir in the market place since people assumed that Malchus had found a buried treasure.

Malchus was brought to the bishop and the mayor and explained to them that he and his friends had the day before fled from the persecutions of Emperor Decius, but he could not understand how the city could have changed so thoroughly during one night and not the least that the behaviour and looks of its inhabitants could have been so utterly transformed overnight. The bishop and the mayor followed Malchus up to the cave, where they among the torn down stone blocks found the parchment that affirmed Malchus story.

They authorities sent for Emperor Theodosius, who at once travelled down to Ephesus, expressly to speak to the resurrected men. After the Seven Sleepers had spoken to the emperor they returned to their cave, laid down and died in their sleep. Almost at once the Seven Sleepers became objects of intense worship, not the least since their long sleep came to be regarded as proof that the death of pious men was nothing more than a long sleep before the upcoming Last Judgment.

Stories about awakened sleepers who have overslept is not an unusual theme in fairy tales. Legends of heroes and villains who sleep for hundreds of years are known worldwide, as well as tales of sleeping beauties, or men who end up in worlds beyond time and space, in mountain caves or under lakes, only after long periods of time to return to places changed beyond recognition. The story of the Seven Sleepers is a legend and as legends commonly do it presents us with name of the actors, the place where the extraordinary event took place and also the time when it all happened.

It is true that Ephesus around 200 AD was largely a Christian city. It had since the 90s been a bishop seat and an important centre for the spread of Christianity. When Decius came to power in the year 250 he was in his fifties and had served as senator, consul, governor and a general for Roman troops stationed in the Balkan, thus he had become convinced that Rome's central power must be secured and all tendencies to split it up contested. Decius regarded Christianity as a state within the state and demanded tangible proofs of the Christian faithfulness to the Roman supremacy.

The sign that the Christians considered themselves as loyal Roman subjects was that they took part in public sacrifices to the Roman emperor's welfare. This did not mean that they renounced their faith, it was only considered as a visible act that they accepted that the State was their superior. Romans generally distinguished between personal piety and the state cult, the latter had nothing to do with an individual's relation to various deities. Sacrifices for the emperor´s health were simply considered as a proof of an acceptance of the governing laws of the State and that those who supported the sacrifices were opposed to anarchy and any opposition to the Government.

If Christians refused to sacrifice for the emperor's welfare it was considered as an open revolutionary act and in accordance with Decius decree punishable with death. If Christians participated in the sacrifice for the Emperor´s wellbeing they received a written statement from the officiating priest to be used as a guarantee that they were not at all opposed to the supremacy of Roman government.

Naturally, the decree caused violent disturbances. Many Christians refused to sacrifice and several of them were sentenced to death. Some Christians´ refusal to sacrifice also led to violent anti-Christian pogroms in Carthage and Alexandria, where mobs incited by demagogues who claimed that the Christians had poisoned public wells, which according to them had led to a violent plague that affected the entire Roman Empire. This is reminiscent of how Christians much later massacred Jews during the Black Death, for similar, equally baseless accusations of well poisoning.

Only two years after his enthronement Decius died in a battle against the Goths, though his decree that all Roman citizens had to sacrifice for the wellbeing of the emperor was not withdrawn until ten years later, when Emperor Gallienus realized that the whole empire was falling apart and he needed the Christian support to preserve it.

It is possible that Decius attacked the Christians of Ephesus particularly hard, but it could not have been as violent as Gregory of Tours described it:

When Decius came to Ephesus, he ordered that Christians be persecuted to the elimination, if possible, of their faith. He burned them amidst their pleas and fear. They burned victims and the whole city went dark with fumes.

According to Gregory, Decius spared seven young people because they were so handsome, that the emperor thought it would be a waste to execute such strong men and suggested to them that they would closely consider their refusal to sacrifice. If they had changed their mind, he would spare them when he returned to Ephesus within a year. Nevertheless, when Decius returned, he found that the seven young Christians had disappeared from the city and through threats and violence, he received information from their relatives that they were hiding in a cave and while the seven men were asleep Decius´ soldiers sealed the cave.

In Orhan Pamuk's novel My Name is Red, stories are intertwined, forming an intricate pattern, a complicated structure. One of the different perspectives is provided a dog, who is being able to transmit his thoughts. A free and fairly ferocious creature that both confirms and denies several Muslims´ aversion to dogs. He tracks different conceptions of dogs' value and characteristics and thus mentions the legend of the Seven Sleepers, stating that if a faithful dog was worthy of being mentioned in the Holy Qur´an this fact is a great honour for any dog. Accordingly do creatures like him merit more respect from orthodox Muslims.

The Qur’an’s eighteenth sura is called The Cave and we understand that this protective cave is equated with the doctrine Allah revealed in the Qur'an:

And now, having abandoned them and what they worship other than God, let us take refuge in a cave, and God will spread out his mercy and make it easy for you to find the prudent path to follow in this matter.

The eighteenth sura is one of the Qur´an´s longer chapters and mentions several myths and legends. It seems to suggest that the legend of the Seven Sleepers was well known in the world in which the Holy Scripture was revealed. Like so much else in the Qur´an, there is a concrete touch to the story. It is for example explained how it came about that the sleepers did not obtain any bedsores during their long sleep on the hard rock and that their dog could keep guard over them:

And you would have imagined them to be awake as they slept on. We would turn them from right side to left, as their dog spread its paws across the entrance.

The Qur'an emphasizes that there is no point to argue about a narrative´s irrelevant particulars, such as to discuss whether the sleepers were three, five or seven in number.

They shall say:”They were three in number, their dog a fourth.” Others will say: “They were five in number, their dog a sixth” – predicting the Unseen. Yet others will say: “Seven, their dog an eighth.” Say: “My Lord knows best what their number was, and none knows it but few.” So do not dispute this issue with them except in a superficial manner, and do not solicit the opinion of any of them concerning their number.

Most important is what the story really tells us, its deeper meaning, namely that truth consists regardless of the passage of time, how much we humans might argue about it. The Qur´an states that the truth behind everything is God's permanent presence. His all-encompassing power persists whatever we humans might undertake. The proof is that when the seven sleepers entered their cave, it was uncertain whether the truth would be able to survive the divisive perceptions of what was right or wrong, but when the sleepers woke up after their three-hundred-years long sleep, the found that truth had triumphed.

What Pamuk´s dog is proud of the fact that it was a dog that was chosen to watch over the sleepers, it seems to imply that he, unlike humans with all their acquired knowledge, through his animal instinct is an integral part of nature and thus represents God´s unwavering order. The laws of God remain forever true. Or as Galileo Galilei observed when, after having been forced to admit that the Earth does not revolve around the sun eppur si muove, "yet it does move".

Incidentally, this neatly expressed opinion, as well as many other famous sayings and quotes, has been questioned. The first time it was mentioned in the literature was in 1757, more than a hundred years after Galileo's death. However, in 1911 a wealthy family in Brussels left a painting to a restaurateur for cleaning. It represented Galileo in a prison cell, and he held a nail in his hand. When the painting had been cleaned it was found it was signed in the year 1643, the year after Galileo's death and that on the prison wall behind the Italian mathematician the words Eppur si muove was engraved. It is known that Galileo's friend Ascanio Piccolimini after the great scientist's death ordered a painting from the famous painter Bartolome Esteban Murillo. However, like most good stories the tale about the lost portrait is also being doubted. The painting has disappeared and it only remains as a reproduction in lot of books about Galileo, where the picture is taken from a book published in 1929.

That we humans, unlike the cats and dogs that we live together with, have no intimate contact with the great, marvellous universe that surrounds us, also pops up in a strange and frankly speaking quite difficult novel by José Saramago. It is called The Cave, and when I read about the Seven Sleepers I came to think about it, not the least since it is a dog Achado, “Found”, which has a leading role in the story. Achado shows up in an abandoned dog house in the potter Cipriano Algor´s garden. Cipriano lives in a depopulated village near a giant Centre, which mercilessly devours not only the world of the humans, but also their entire way of thinking. An artificial consumption and residential conglomerate where large, artificial establishments are made to imitate nature - storms, lush vegetation, waterfalls, etc. It is the market forces that govern The Centre. Unceasing control and security measures make residents losing their personality and reduce them to mere consumers.

Even the potter Cipriano is pulled into The Centre's relentless march forward. Though the dog Achado saves him from losing his soul. Achado is part of the reality - nature - that surrounds us all, completely in accordance with Galileo's observation eppur si muove. Like the Seven Sleepers in their cave are protected by their faithful dog, Achado is watching over Cipriano. The dog's secure patience, sincere loyalty, tenderness and tranquillity that Ciproano finds reflected in Achado´s gaze make the redundant potter (The Centre has replaced his earthenware with plastic products) relaize the deep love he has for his daughter and her husband. Achado appeared at Cipriano´s place out of his own free will. Cipriano´s realization that the dog actually chose to live with him and thereby abandoned his previous existence makes it possible for the potter to make the decision to liberate himself and his loved ones from The Centre's ever increasing and immersive parasitism.

All this being said does not mean that I appreciated Saramago's novel in full – the style was far too heavy, too compact and preaching, the parables were too obvious, but in spite of this the story stuck with me. Maybe since its description of different characters was strong and I thus could identify with the poor Cipriano, a loser about the same age as me.

All these stories about sleeping and waking up to strange worlds made me think about how it might feel like to have lost a large part of your life. People who have lost their lives in work, dreams and illusions. Who believed that an attractive, though unrealised future might release them from all their troubles and shortcomings; that money, fame and admiration will finally be bestowed upon them and make them happy. People who have not realized the truth of John Lennon's beautiful words in the song to his son Sean, Beautiful Boy:

Before you cross the street take my hand.

Life is what happens to you while you're busy making other plans

We read and hear about people who have been imprisoned year out and year in, only to be released into an alien world. An essential theme in masterpieces like Chaplin's Modern Times and Döblin's Berlin Alexanderplatz. There are plenty of examples of individuals, both guilty and innocent, who have lost their lives in prisons and labour camps, simply to be thrown headlong into worlds that have changed beyond recognition and where no one seems to know them anymore.

An entertaining story about a sleeper is Washington Irving's short story Rip Van Winkle from his collection The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gen. It tells the story about a charming lazybones who suffered hard after having married a stern lady who constantly, and with good reason, complained about him. Rip stayed as often as possible away from home, roaming in the forests, fishing or helping neighbours and friends with errands and odd jobs that "men avoid doing in their own homes." He was popular with everyone, except his wife who:

… kept continually dinning in his ears about his idleness, his carelessness, and the ruin he was bringing to his family. Morning, noon, and night, her tongue was incessantly going and everything she said or did was sure to produce a torrent of household eloquence. Rip had but one way of replying to all lectures of the kind, and that by frequent use had grown in to a habit. He shrugged his shoulders, shook his head, cast up his eyes, but said nothing. This, however, always provoked a fresh volley from his wife; so that he was fain to draw off his forces, and take to the outside of the house – the only side, which in truth, belongs to a henpecked husband.

A sunny day Rip van Winkle wandered far away, in among the Catskill Mountains, which the Hudson River is winding through. In a glade he surprised a peculiar group of under seized men, who dressed in archaic clothes played nine-pin bowling. They were unusually taciturn and serious, but generously offered Rip a large flagon with a tasty drink reminding him of excellent Dutch ale, before they doggedly return to their skittles. Mug after mug with the tasty ale, mixed with the muffled rumbling of the wooden balls made Rip fall asleep on the deep, cushy grass.

When he woke up, it was a warm and sunny morning. When he came up on his feet he was surprised by how stiff his joints had become and assumed the hard ground had given him a bout of rheumatism. His clothes were worn and torn: "Oh" he thought, "that wicked flagon! What excuse shall I make to Dame Van Winkle?” He was looking for his gun, but in its place there was an old firelock with its barrel incrusted with rust, the lock falling off and the stock worm-eaten. When he called his faithful it refused to appear. On his way home Rip marvelled at how there was a mountain stream where there had been a ditch the day before, and he became even more amazed when he arrived in his home village and found that people were pointing fingers at him. They seemed to be both amazed and worried. He put his hand to his face and found that it was wrinkled and an unkempt beard had grown a foot long.

When Rip faltered to his home, he found a dilapidated, overgrown hovel. Soon, he encountered a couple of old men and under their beards and wrinkles they revealed themselves as his old drinking cronies, telling him that he had been missing for over twenty years. Rip van Winkle´s wife had died long ago, after a vein had ruptured in a fit of passion at a New England peddler. Rip´s children were grown-ups. The boy was the same lazy fellow as Rip once had been, but the daughter wass both beautiful and thrifty and allowed her aged father to stay with her and her family.

An old man explained that Rip Van Winkle had fallen victim to Henry Hudson and his men, who after their death for more than one hundred and fifty years ago every twenty years was having a party while they visited the place where they once had anchored and where their captain gave the river its name. They then drank a beverage that kept them alive, but at the same time caused them to wake up just for one day and night in every twenty years´ time. It was such a drink they had invited Rip Van Winkle to. The villagers assumed that this might be the only explanation to why an aged Rip had appeared in their village after twenty years of deep sleep.

Oddly enough Rip Van Winkle did not regret that he had slept away twenty years of his life. Instead, he was pleased by the fact that his wife had died and that he, as an old man, was not expected to do any hard work but could devote himself to his favourite pastimes - fishing, walking and tell stories to the village children.

For sure, reality is much worse. Rip Van Winkle slept away twenty years of his life, but other men and women have lost year after year in hell, which they every morning were forced to wake up to. As in Primo Levi´s horrifying memories from Auschwitz where shouts of Wstavac! and Aufstehen! were dreaded because they signify a new day of unfathomable suffering. Have you been imprisoned, racked and separated from normal life you cannot become the same person you were before you entered the gates of hell.

Andrzej Wajda's film Landscape After Battle begins with scenes of how concentration camp inmates in striped prison clothes, to the triumphant sounds of Vivaldi's The Spring, comes running towards us in a drab, grey winter landscape A man walks up to the barbed wire fence and gently grasps a wire - there is no deadly current. He and several others tear down the barbed wire and rush out into the empty, snow-covered landscape. Out there, they meet soldiers and embrace them. Though after a while close-ups reveal bewilderment in the once joyous faces, people do not know where to go and slowly return back towards the barracks, where other groups of prisoners are waiting. The music, which for a while has calmed down, again becomes cheerful and sprightly. Liberated inmates smash windows, burn books, gobble down food (but we see that it makes them sick), hunt down and kill camp guards, undress in the snow, while they naked burn their prison clothes. However, the music once more becomes subdued, melancholic. Once again close-ups of confused faces. Men move between barbed wire fences, or across barren fields. Snow, cold, greyness, emptiness.

Wajda´s movie is based on parts of Tadeusz Borowski´s memories from his time in Auschwitz - This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen, a book filled with scenes drilling into your memory. Like Wajda´s movie Borowski´s text swings between close-ups and group shots, activity and reflection, empty landscapes and cramped rooms, portraying Auschwitz, the terrible numbness and emptiness that reigned there and continued to haunt those who survived that hell. Like so many others survived the concentration camps and told as about them, like Primo Levi and Paul Celan, Borowski took his own life.

When I asked my high school pupils, which was their favourite movie they seemed to be almost unanimously in agreement that it was Shawshank Redemption by Frank Darabont. I was surprised, particularly since that film was made in 1994, long before they were born. But their choice was understandable, it is an excellent movie about lost lives and fulfilled dreams, a film about a miracle. It seems that schoolchildren could almost instinctively identify themselves with lifetime prisoners in an inhumane prison. As students they are forced to go to school every work day, while constantly being judged as individuals and according to their efforts. The burden of homework and tests may for some of them be devastating, in particularly if they are constantly monitored by demanding teachers and parents. Most of them certainly dream about a final exemption from the school treadmill, a liberation that might direct them towards money and success.

Darabont´s film is based on a short story by Stephen King Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption, in which he lets an old jailbird, Red (in the movie played by Morgan Freeman) tell the story about a man who with intelligence and infinite patience managed to damage the system and turn himself into free man. When Stephen King is in great form, he is very good. Red tells his story in a dry, cynical and colloquial manner. Listen to him describing his hero Andy Dufresne´s predecessor as prison librarian. An institutionalized man imprisoned for over thirty years, Brooks Hatlen had once in drunken madness killed his wife and daughter, but was finally pardoned:

He was sixty-eight and arthritic when he tottered out of the main gate in his Polish suit and his French shoes, his parole papers in one hand and a Greyhound bus ticket in the other. He was crying when he left. Shawshank was his world. What lay beyond its walls was as terrible to Brooks as the Western Seas had been to superstitious fifteenth-century sailors. In prison, Brooksie had been a person of some importance. He was the librarian, an educated man. If he went to the Kittery library and asked for a job, they wouldn’t even give him a library card. I heard he died in a home for indigent old folks up Freeport way in 1953, and at that he lasted about six months longer than I thought he would. Yeah, I guess the State got its own back on Brooksie, all right. They trained him to like it inside the shithouse and then they threw him out.

In his movie Frank Darabont expands the poor librarian´s pathetic role and deepens it further. In an interview he explained:

I realized that Brooks Hatlen, a character mentioned in passing in one paragraph of the novella, needed to be a main character, and that we needed to see his experience in order to relate to the entire theme of the movie, and to Red’s (Morgan Freeman) experience at the end of the movie.

In the movie the library of the calm and resigned Brooks Hatlen becomes a sanctuary for the abused, beaten and battered Andy Dufresne, a place where he finds strength to slowly and patiently put together his great and complicated escape plan. Like Burt Lancaster in John Frankenheimer´s Birdman of Alcatraz, Brooks Hatlen keeps a tame bird, a crow called Jake. When he finally is pardoned, Brooks releases Jake and takes the bus back to freedom, where he is shocked by the changes - houses, cars, people, all the stress, all the bustle, the terrible loneliness in the middle of a seething life. He ends up in a dreary rehabilitation apartment and works packing merchandize into bags at a supermarket. Finally, Brooks writes a letter to his prison pals, describing his fears, his loneliness and feeling of worthlessness. On a roof beam in his depressing abode, he carves the message "Brooks was here", before he attaches a rope around it and hangs himself. When Red finally comes out of prison, he ends up on the same flophouse and when he sees the words that Brooks carved on the beam Red realizes that he also is doomed to despair and misery, but a miracle delivers him - Redemption in the form of a message from his friend and hero Andy Dufresne.

I read King's short story four years after I during a summer had worked at Saint Lars´ mental hospital in Lund, Sweden. Even then I was impressed by the short and admirably concentrated paragraph about Brooks Hatlen´s fate. I was once again and even stronger reminded of my time at Saint Lars when I ten years later saw the movie.

Just like in Milos Forman's One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest the patients at Sankt Lars regularly received their small plastic cups with differently coloured psychotropic drugs. I believe that those drugs, combined with the stupefying boredom of the day area and the individual rooms, were instrumental in making the inmates severely institutionalized. The day room was bright and quite nicely furnished, with comfortable sofas, potted plants, board games, books and magazines. The patients could come out into the kitchen to get coffee, mineral water and slices of a sweet loaf, which I will never forget and surely will not eat again, though the food was quite decent. They were dressed in their everyday clothes and occasionally I found the patients nicer and more normal than some of the personell.

I got talking to an elderly gentleman who had been detained since his youth, sometime in the late 1930s. He had been an underpaid farmhand and in youthful bravado put fire on the residence of the landlord. I do not remember if anyone had died or been injured due to the fire, but the perpetrator was interned as "mentally unreliable" and had since then been shuffled from institution to institution, until he ended up in the sofa in the day area at Saint Lars, where he sat reading a newspaper or a book. He was somewhat lethargic in his speech, but to me he gave the impression of being quite normal and when I asked the personnel about him they were all agreed that it was not really anything wrong with him, other than that the constant medication had dulled him down and the medical doctors considered it would be irresponsible to release him outside of Saint Lars´ gates.

What surprised me when I spoke with the patients was that they, contrary to what I had assumed, considered themselves to be in need of care. Even the old man, who when I asked him why replied: "I don´t know about anything else and I don´t want to know anything else either."

Borowski, Tadeusz (1992) This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen. London: Penguin Classics. Paul the Deacon (2003) History of the Lombards. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Drake, Stillman (1995) Galileo at Work: His Scientific Biography. New York: Dover Publications. Gibbon, Edward (2005) The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: Abridged Edition. London: Penguin Classics. Gregory of Tours (1974) History of the Franks. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics. Irving, Washington (2012) Legend of Sleepy Hollow and other stories. London: HarperColllins. Khalidi, Tarif (2008) The Qur´an. A New Translation. London: Penguin Classics. King, Stephen (1982) “Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption” in Different Seasons. New York: Viking Press. Saramago, José (2002) The Cave. New York: Harcourt. Pamuk, Orhan (2002) My Name is Red. New York: Vintage Books. Potter, David S. (2002) The Roman Empire at Bay AD 180–395. London and New York: Routledge. Voragine, Jacobo di (1998) The Golden Legend: Selections. London: Penguin Classics.