A DOG´S LIFE: To be together in different worlds

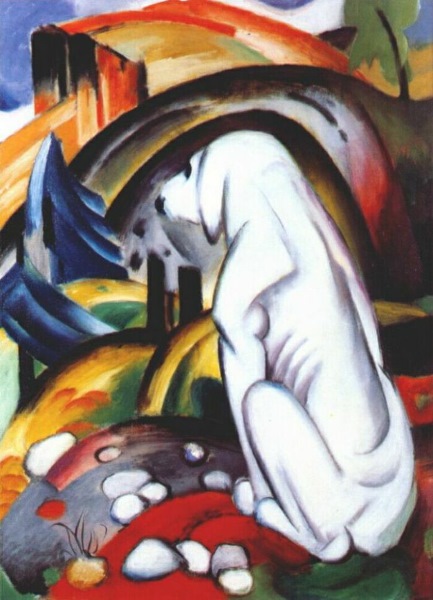

The morning mist has lifted, but remains blue whitish high above the landscape, without an opening towards the bright blue expanse behind it. Water droplets hang on bare branches, the ground is covered by rust brown leaves. Except for a faint sound of dripping water, the forest stands muted, saturated with a scent of decomposing leaves and juicy moss. Between black trunks and tangled branches there are glimpses of the last, lingering leaves. Autumn has passed by, only maple and aspen retain their intense yellow leaves, glowing in a moisture-laden greyness. After a violent storm a few years ago brought down the tall pines, the forest behind my mother's house is tangled and ugly, but on this gloomy morning it is beautiful.

I walk along the usual path with Mio, my mother's aging Labrador, her legs are getting rigid from old age and her hearing is deteriorating. Nevertheless, she is as sprightly as a puppy when we start our walk together, only gradually she slows down and more and more often stay to gravely examine a shrub, or exploratory drill down her nose among wet leaves, then she trots on, either before or after me. Sometimes she makes a halt and looks at me with her wondering dog eyes. They are inscrutable. Something is hidden behind them, but I do not understand what can be, only that her glances are filled with trusting affection, neither evil nor malice.

I stop, she sits down and looks up at me in surprise. When she looks me into the eyes I remember how I several years ago for a couple of days worked as a substitute in a primary class. The children were curious about their temporary replacement, sat quietly and listened intently to what I had to say. I was scheduled to teach religion; specifically how people perceive God and of course there was a well-behaved boy who came up with the worn phrase: "I do not think that God is an old man with a beard sitting on a throne up in Heaven." "How is he then?" "I think he looks like an ordinary person." "What do you mean by “ordinary?" "My parents have told me he looks like that. However, they also said that he does not have a white, long beard. He looks nothing like a Santa Claus." "How could they be so sure about God´s looks?” I wondered and suddenly realized that I had to choose my words carefully and avoid the categorical statements that tend to fall out of my mouth with far too much ease. Much later one of my bosses rebuked me sternly, stating: "You have to edit yourself, Jan!"

The boy shrugged, looked me deep into the eyes and asked: "You ought to know. It is you who are the teacher. You have read more than my Mom and Dad. What do you know about God´s looks? Is he dressed in a suit?" His question sent me straight out into the swamp, I had ended up in a quagmire. Twenty interested pairs of eyes turned towards me. I did not know who the boy was and did not want to tangle up his beliefs. Not make him doubtful about his beliefs, or questioning parental authority. There is always the risk that guardians call the principal and complain about my poor teaching. A teacher's constant fear. I was young and inexperienced, but I could obviously not remain silent. My authority was at stake. I grabbed a straw. Since I had recently passed the undergraduate course in History of Religions, I knew that a Church Father called Clement of Alexandria had quoted a Greek philosopher, named Xenophanes of Colophon, who had written:

But if cattle and horses and lions had hands, or could paint with their hands and create works such as men do, horses like horses and cattle like cattle, also would depict the gods' shapes and make their bodies of such a sort as the form they themselves have. […] Ethiopians say that their gods are snub–nosed and black. Thrachians that they are pale and red-haired.

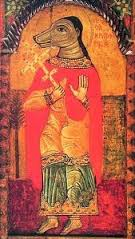

As usual, I had got the quote wrong, bur remembered its meaning and said: "We find it hard to imagine things that we cannot compare with something we already know. Since we do not know what God looks like we imagine that he looks like a man. If dogs believed in a god, they would probably assume that he looked like a dog." A little girl behind the desk right in front of me looked up thoughtfully, then she held up her hand and asked with great seriousness: "Do you think that God might be a Labrador?”

The memory made me smile as I watched Mio where she sat and cocked her head in an attempt to figure out what I was after. If God is good, he might have some similarities with an old Labrador female, at any rate I cannot find any trace of evil in her.

We continued our walk through the woods. I began to plan a new blog entry and thoughts span in my head. I felt a connection, a sympathy with the dog that sauntered a few feet in front of me. She shone white in the gray, dark forest. In the old Viking tale of Ragnar Lodbrok, the chieftain Ragnar wants to test the wits of the beautiful virgin Kraka by asking her to come down to his ships, neither clothed or naked, neither hungry or satisfied, neither alone or in company. Kraka comes to him wearing a fishnet, with an onion in her mouth and only a dog for company.

Perhaps something similar could be said about me while I was walking the woods with Mio. She was a fine company, but nevertheless, I was alone with myself and my thoughts. The dog and I exist in separate realities even if we inbabit the same abode. As in the Swedish poet Lars Gustafsson's Elegy for a dead Labrador:

Our friendship was of course a compromise; we lived

in two different worlds: mine,

mostly letters, a text passing through life,

yours, mostly smells. You had knowledge

I would have given much to possess:

the ability to let a feeling – eagerness, hate, or love -

run like a wave throughout your body,

from nose to tip of tail […]

Why couldn´t I learn from you? And doors.

In front of closed doors you lay down and slept,

sure that sooner or later the one would come,

who´d open the door. You were right.

I was wrong. Now I ask myself, now when

this long mute friendship is forever finished,

if possibly there was ever something I could do

which impressed you. Your firm conviction

that I called up the thunderstorms

doesn´t count. That was a mistake. I think

my certain faith that the ball existed,

even when hidden behind the couch,

somehow gave you an inkling of my world,

in my world most things were hidden behind something else.

I called you ”dog”.

I really wonder if you perceived me

as a larger, noisier ”dog”,

or as something different, forever unknown,

which is what it is, existing in that attribute

it exists in, a whistle

though the nocturnal park one has got used to

returning to without actually knowing

what it is one is returning to. About you

and who you were, I knew no more. [...]

We and the animals are together with one another, yet alone. Strangers learn from one another, Just like Gustafsson believed he could learn something from his Labrador, I assume I can learn something from Mio.

In his his books of thoughts Murene rundt Jeriko (The Walls around Jericho) the Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose walks around sullen, bitter and grumpy in his house and the area around it. After his wife and one of his sons have died of cancer, he is left in an isolated house in the wilderness, with a son, a few chickens, a horse and a dog. Surrounding him is the magnificent Norwegian nature, with its short summers and long winters. Sad, angry and with a strong sense of failure, Sandemose allows his thoughts to wander back and forth.

The surviving son, twin of the dead brother, has like many other writers´ children directed a terrible curse against his dead father. In a more than six hundred pages long biography he portrayed him as a violent drunkard, a drug addict, notorious liar, wife abusing misogynist, a self-centred cheater poisoned by cynicism and of sickly delusions. In spite of all this Aksel Sandemose remains an often brilliant stylist and in his writings plenty of thoughtful formulations are to be found.

The son writes that his father lived within a drunken chaos, neglecting house and animals. He even could shoot their dogs if they, according to him, became too unruly. In The Walls of Jericho Sandemose still writes about his boxer Jasper with appreciation and empathy, as in a description of how they walk through the deep forest to post a letter. A scene I sometimes think of when I am out walking with Mio. It is not much more than a grove of trees we are walking through, though she is a dog, and as such she feels and knows things I cannot imagine. She constitutes a link between me and nature, as when Sandemose´s dog opens up nature and centuries for him:

It was the first hour of a faint dawn. Jasper, who was on a leash, was excited and crossed the trail from side to side. He had to voluptuously draw all the nice, fresh and nocturnal tracks into his brain. The smell of wood mice, hare, deer, moose, fox and certainly also the badger - now when we had been granted spring as a gift - the marten and the neighbor's cat, alien horse and stranger, as well as the capercaillie that often took this path in the evening. Through my dog's nose I felt like a part of creation's enormous flock; a strange relative to other strange beings that crept up in the woodlands, or sat sleeping in the trees. The deep-rooted trees that belonged to the family of the living. Almost imperceptibly the dead also joined the entourage, thousands of animals and people who for millennia had passed along this road within a sparsely populated area, and now were rotting in the soil.

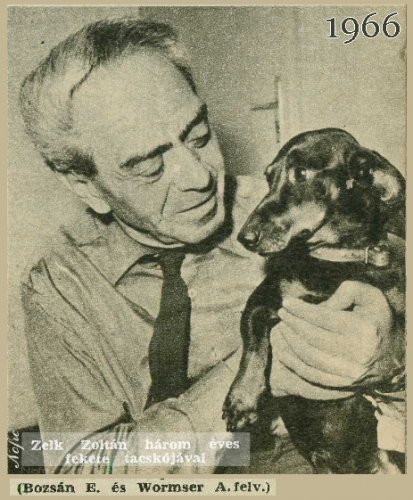

There are novels entirely based on a dog´s perspective. Unforgettable are of course Jack London's Call of the Wild and White Fang, but the best book I´ve read about a dog is Tibor Dérys Niki: The Story of a Dog. As one of Hungary's best and boldest writers Tibor Déry did during the revolt of 1956 join Imry Nagy's Government and also wrote his novel about a mottled, small and wirehaired terrier bitch. After the failed revolt, Déry was sentenced to nine years in prison, but he was released in 1960.

Déry´s tale is a subtle portrayal where life is commented upon through a small dog's fate, while telling about her and her masters´ troublesome existence Déry succeeds in keeping a certain distance to his own tale, but nevertheless manages to make it tender and beautiful. The loyal and playful bitch does through its own accord find a young couple, where the husband is an engineer and his wife works as a volunteer for the Communist Party. After initially having been averse to the little stranger who has chosen them as objects for her steadfast love Niki, as the dog is called, soon becomes the center of the childless couple's affection. Her presence make them even closer than before she made her appearance. Niki considers herself and her masters as members of the same family pack:

When, as very rarely happened, the pair set out together of a Sunday for a walk along the embarkment [...] Niki was was beside herself with joy. When this happened, and when the engineer, ready before his wife, started down the stairs, the terrier would run after him but, arriving at the first landing, would go rushing back to the flat, insistently summoning Mrs Ancsa to hurry, and returning to delay Mr Ancsa by playing about his feet, and so until she saw them together.

Much of the novel´s charm lies in the fact that Déry is a sharp observer of the dog's different moods and behavior. Page after page he succeeds in varying such observations - how Niki is chasing after a rabbit, how she forgets herself while playing with other dogs. How she observes her masters´ and other humans´ incomprehensible behavior; her sadness, joy, pain, boundless faithfulness and love. One of many examples of how Déry applies a "dog perspective" is his description is when he describes how Niki gets a football:

Niki gave this round and unfamiliar object a look of indifference, rose slowly from her cusion and took her time over streching. First she extended her forlegs as far as she could, and with her head on the carpet and her hindquarters in the air, made all her joints crack [...] The engineer waited patiently. When, in her own time, the bitch came towards him. Ancsa threw the ball, which bounced off the floor right under Niki´s nose. For a moment Niki seemed pertified. But in the next moment she was dancing across the flat after the ball in a mad saraband.

The chair beside the hearth went over with a deafining crash. The engineer saw its four legs upwards in the same moment that Niki knocked the vase off the work-table at the other end of the room. The vase had hardly reached the floor, when the standard lamp between the window in the next room went down across the sideboard. Too hard and too smooth for the bitch to get her teeth into it, the ball, like a thing bewitched, constantly got away from her, bouncing wildly all over the flat and always just out of reach, Niki´s slaiva making it more slippery every time she nearly caught it. The whole flat rang with the furious barking of a hunting terrier. […] A few days later only fragments of the ball remained and these, one by one, were lost under this or that artcile of furniture. But the last shred left to her, although no bigger than a man´s thumb, still enabled Niki to fly into a passion of furious action as wild as when the ball was supple and brand new: she bit it and tore it and ripped it up for the hundredth time.

Through this description the reader should not get the idea that Niki was a violent animal. On the contrary, she was an extremely affectionate dog. Déry writes that "she was a sentimental little creature", as when she tried to comfort her mistress:

She cried, with Niki on her lap. Niki, who very rarely saw her mistress cry, was soon affected by this breakdown. She became agitated and began to whine herself, thrusting her cool, black nose gently against her mistress´s face. There was a thing she did when she wanted to ask forgiveness for a peccadillo, or to beg a favour: she would turn back her upper lip, exposing her gums as if she was roaring with laughter, and leaping into the air touch her mistress´s face with her gleaming white teeth and pink tongue. This she did now, when she saw Mrs Ancsa in tears. And then, standing on the unhappy wpman´s knees and unable to reach her face, for she had covered it with her hands, Niki began licking the back of Mrs Ancsa´s neck with her warm tongue.

The young woman is depressed after her husband, without any explanation, has been imprisoned by the Communist regime. She is defenseless, without income and security. Against all odds, she keeps the dog and they become closer and closer to each other. Niki gives her mistress comfort and strength during the five years that her husband is incarcerated, without her knowing where or why.

Niki is a story about the "little life". The reader is not directly informed about the changes, legal uncertainty and misery that befall postwar Hungary, harsh circumstances are only alluded to through the small dog's behavior. The rugged and faithful Niki becomes a symbol for of the Hungarians who through no fault of their own, or maybe due to insufficient understanding, fear, or conformity are subjected to a repressive regime's arbitrariness and terror. It is not difficult to understand why a seemingly simple and harmless portrayal of a confident terrier could be turned into a contributing factor to Dérys long prison sentence. At the end of the novel the unfortunate engineer returns home, worn and aged, with a bouquet of yellow flowers in his hand:

His wife was still holding him in her arms. For the time being she knew nothing, cared for nothing except that her husband had come back. She asked him for the hundreth time, how he had been released, how he had been told of his release, and if he was well, if he wanted anything to eat, or to go to bed and sleep. The engineer held her hands and said nothing.´Were you told why you were arrested?´´No´, the engineer replied, ´I was told nothing`. ´And you don´t know, either, why you were released?´´No´, the engineer replied, ´I wasn´t told.´

Four years before Déry wrote his novel came Vittorio De Sica´s heartbreakingly tragic film about another little, spotted terrier who did anything to help his master - Flike who comforted the luckless Umberto D; a poor pensionerwho after having been evicted from his home plans to kill himself after desperately trying to find a safe haven for his beloved dog. In the final scene, the dog the dog prevents his master from throwing himself under a train and Umberto finally realizes that Flike´s love, after all, might give him the strength he needs to survive. Much later, it is also a small terrier who hinders his hapless master from committing suicide, this time in the Frenchman Hazanavicius´ Oscar-winning silent movie The Artist from 2011.

After I came back home to my mother and we sit and eat together, we throw a glance at Mio who is sitting nearby, watching us with her sad eyes. My mother asks as so often before: "What do you think she would say if she could speak?" I think about my pupils' musings about God´s looks and wonders about how Mio might perceive me and my mother as we sit there and talk about her. She tilts her head and wags her tail.

Déry, Tibor (2009) Niki: The Story of a Dog. New York: New York Review Books. Gustafsson, Lars (1988) The Stillness of the World Before Bach: New Selected Poems.New York: New Directions Books. Xenophon of Colophon (2001) Fragments: A Text and Translation with a Commentary by J.H. Lesher. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.