A RUSSIAN ON MANHATTAN

A few days ago I saw an uneven, funny, sentimental and warm film, filled with clichés about musical, gypsies involved in petty crime, crazy, immensely rich gangster oligarchs, hibernating Communist romantics, Jews interested in making money and vodka guzzling, careless, unkempt Russians, all equally warm hearted and nice people, who had succeeded in surviving the insane Soviet oppression with wits and humor intact. A modern fairy tale, with the naive charm of such a tale. Well-made and well-acted as the film was, in spite of all its burlesque madness, I was charmed by the human warmth it expressed. As I now discovered that it was made by the Romanian-born, nowadays French director, Radu Mihăileanu, who made Train of Life, I understood why I liked it, despite the fact that this film, Le Concert from 2009, was inferior to that masterpiece.

I saw the movie together with Rose and remembered a distant episode in our life, then we are a newlyweds come to New York after my life's second flight, the first had been between Edinburgh and Copenhagen. But, before I get there - let me take you to Russia and Trollhättan of the twenties.

During the chaos that followed the First World War, Russia became the horror and hope of the world. The emerging nation was either feared as the arrival of Antichrist, or as a budding Paradise. In any event, the civil wars and the attack on Poland had come with a high price. The economy was in shambles, industries and fields destroyed, livestock killed, raw material wasted or pillaged, mines blasted or flooded. In 1922, industrial production had shrunk to one-seventh of what it had been in 1913 and agricultural production to a third.

The terrible scale of the disaster is evidenced by the loss of lives, the immense scale of this slaughter is virtually impossible to establish. A conservative estimate sets the number of soldiers killed in action at 300 000 (an estimated 1.8 million had already died during World War I), 450 000 men had died from epidemics and diseases. On top of that was the "Red Terror", which instigated at least 250 000 summary executions. From 300 000 to 500 000 Cossacks were killed or deported. 100 000 Jews had been killed in Ukraine. Crop failures and repressive policies led in 1921 to at least two million dead and additionally recurrent epidemics harvested millions of victims. Only in 1920 three million Russians died in typhoid. In 1922, there were an estimated 7 million street children in Russia, which in December 1922 became Soviet Union.

In early 1920, The Allied Powers´ blockade of Russia was lifted and after two years it was once again possible to trade with the vast country. For the daring and already wealthy, there was big money to earn. However, the Swedish government and most capitalists of this nation wanted to avoid doing business directly with the Bolshevik regime, partly for ideological reasons, partly because it was feared that the Bolshevik regime would fail to hold on to power for a longer time. If the Bolsheviks were toppled, there was no guarantee that their successors would approve of any agreement concluded with their enemies. Therefore, the Russians got no credit. If they wanted to do business, everything had to be paid for in cash. Negotiations between Swedish stakeholders and the Bolshevik regime had to through Swedish lawyers negotiating with Centrosoyuz, the All-Russian Association of Consumer Associations.

If the wheels would begin to roll in the Russian economy, the transport system had to be rehabilitated as soon as possible. Railways and bridges were destroyed and of the about

25 000 locomotives that existed in the country before World War I, there were only 5 000 left, most of them in a poor condition. It was not possible to start a national production within a reasonable time; new locomotives had to be acquired from abroad.

The Swedish locomotive manufacturers Nydqusit & Holm, NOHAB in Trollhättan found themselves on the verge of bankruptcy. European railways were being electrified at a rapid pace and if the company would survive, production must be changed and renovated, especially since the German industry began to get on its feet after the war and soon would constitute a deadly competitor. The son of a well-known Trollhättan-contractor, Gunnar W. Andersson, got through one of his friends, the lawyer Hellberg in Stockholm, information about the Russians' interest in buying locomotives. Andersson had in pre-revolutionary Russia been the representative of a German wool manufacturer and had through his own firm in Stockholm continued to do business with the vast land in the east. After the October Revolution of 1917, he sold large parties scythes, made at a Swedish scythe factory in which he had interests. These transactions were mediated by the lawyer Hellberg and a former fellow student of Andersson, who was a resident of St. Petersburg.

Hellberg and the previous classmate were able to convince the bold Andersson that if he dared to benefit from the Russian desperation, he could make a fortune in the process. Andersson put all his effort into the endeavor and after having managed to convince several banks and other stakeholders, he managed to scrape together enough capital to buy NOHAB in Trollhättan and in Copenhagen begin negotiations with the Russian "communication dictator", Leonid Krassin.

The Russians were eager to order their locomotives and willing to pay cash in advance. In May 1920, an agreement was signed between Centrosoyuz and Gunnar W. Andersson for the delivery of 1 000 large freight locomotives at a price of 230 000Swedish Crowns per piece. The whole affair was would thus amount to 230 million SEK (which at the time was equivalent of), so far the largest single locomotive order in the world. A certain percentage of the price was to be paid in advance and the rest upon delivery. Everything was to be paid in gold, which would be deposited with the vaults of the Swedish National Bank in Stockholm. An advance of 7 million SEK was granted.

On the first in December 1920, ten tons of minted gold, the equivalent of 26 million Swedish Crowns were brought on a Swedish ship from Tallinn to Stockholm. Upon arrival, the coffins were transferred directly to the National Bank. The Russian gold exports caused a sensation. The French protested as they, due to outstanding loans to Russia, claimed to have a greater right to the gold. Even the US Government was angered, but the two governments soon quieted down their protests and much of the gold was sold in Paris and forwarded to the United States.

Soon, the steam engines were loaded onto ships bound for Russia. They were considered as veritable monster locomotives, but were in fact not larger than Swedish locomotives which were used to transport iron ore, though the boilers were placed higher something that made the Russian engines look much bigger. After a little less than two years of uninterrupted delivery the Russians broke the contract with NOHAB. The order was limited to 500 locomotives; the remaining 500 would be manufactured in Germany. The Germans had offered to produce them for half the price.

At a conference in the Italian Rapallo the German and Russian Foreign Ministers, Rathenau and Tjijerin, had agreed that if Russia renounced their claims for war damages, they would instead invest 4 billion Reichsmarks in the German industry. This was a hard blow for NOHAB. The deal had so far given a surplus of 15 million SEK, but earnings had been spent expended on new buildings and acquisitions. After extensive cuts and dismissals NOHAB survived by a whisker.

This story became the origin of a Russian-Swedish idea to create a romantic movie epic, a kind of counterpart to David Lean's blockbuster Doctor Zjivago from 1965, the year that Mikhail Sholokhov had received the Nobel Prize in Literature (exactly one year after Leonid Brezhnev had come to power), possibly as a kind of excuse because the Swedish Academy had angered Soviet authorities by presenting Zjivago´s author Boris Pasternak with the price in 1958. A year after the film Doctor Zjivago had SF, the Swedish Film Industry, signed an agreement with Gorky Film in Moscow to co-produce a film about Lenin´s locomotive deal with NOHAB. The production of The Man from the Oher Side, as the film was to be called, attracted much attention in the press. This was partly due to the unique Russia /Swedish co-operation, and on the film's high production costs of SEK 11 million - the hitherto most expensive Swedish film.

To spice up the story of the locomotive deal a tragic love story was invented, it was to be developing between a beautiful Swedish high society lady called Britt Stagnelius and a handsome, Bolshevik engineer, Viktor Krymov, The Man from the Other Side. Krymov was to be played by the popular heartthrob Slava Tikhonov, while Britt Stagnelius was acted by Bibi Andersson, who after Ingmar Bergman's Persona was admired by cineastes around the world and by many considered as the prototype for Nordic beauty. One who had seen and been impressed by Persona was the Russian director Mikhail Bogin, who recently had received good Russian reviews for Zosya, a film about a tender relationship between a Russian officer and a Polish peasant lady during a short period of tranquility during World War II. Despite his relative youth, he was thirty at the time, Bogin was considered as good choice for providing a human and compassionate dimension to the otherwise difficult task of making a romantic epic around the rather mundane dealings around the purchase of locomotives. It was Bogin who had insisted subcontracting Bibi Andersson. However, the script was delayed, re-written time and time again, passing from hand to hand. The Swedish SF tired and the entire project was at the Swedish transferred to other producers and it eventually was agreed that the imaginatively minded Bogin would be replaced with the more seasoned, but rather inconspicuous Yuri Yegerov, who was lecturer at the Moscow Film College (VGIK) and had twelve films behind him.

The filming took place from September 1969 to February 1970, but the editing proved to be very complicated and took more than a year to complete. The film was an embarrassing failure, "a beautiful but bland film, with a syrupy, clichéd love story." Even if being a passionate movie-goer I had never heard of, or eventually totally forgotten about The Man from the Other Side until my friend, teacher and neighbor Sverker Hällen, showed up with a wrapped present the day before Rose and I got married and went to New York.

When I feel that my students are unhappy with me, or my teaching, I use a lousy self-defense by telling them that even if they suffer from inane teachers they should not give up, but continue to struggle with the school and not let their future be predestined by an idiot. Personally, I think I have had far more incompetent than good teachers, but those who were skilled and engaging have in return meant a lot to me. Among the few good teachers who have changed my destiny I include Sverker, who for a time was my teacher in practical filmmaking.

Sverker Hällen is a tall man with a bushy beard and a usually severe countenance, but he has a very good sense of humor and a warm heart. He is an upright man who does not hide his honest opinions and is prepared to assert his uniqueness. Knowledgeable in many areas, not least in film, art and literature, Sverker has always something interesting and unexpected to say. He is also steadfast in his friendship and although I have not seen him in many years, I know we will get on well when we meet again.

I learned a lot about film from Sverker and the appreciation of the craft I believe I can discern behind the movies I watch, I have largely him to give thanks to. When I moved in with Rose Sverker lived with his family on the other side of the street and at times he dropped in to visit us. It also happened I met Sverker at Spisen on the stove, a tavern in Lund where I often sat in a corner with my friends, especially during my bachelor years. In the same corner, I also used to meet the original Situationist artist Jean Sellem and the eternal student Maxwell Overton. Sellem always drank tea, while Maxwell drank the cheap, white wine Beyaz, in which he dissolved sugar cubes. Maxwell had students as lodgers in his large apartment, in which several rooms from floor to ceiling were filled with newspapers which narrow walkways between them. My friend Mats was for a time a lodger in Maxwell´s strange place.

I met Rose in October 1978 and in the spring of 1980 we prepared ourselves for our first joint trip to her home country, the Dominican Republic. Some time before our departure we received a message from Rose's mother in which she wrote that we were very welcome, but we should get married before we got there. We had not counted on that and I hurried down to bureau of the Cathedral to find out if I and Rose could be married as soon as possible. It turned out to be more complicated than I had thought. The priest must namely during three consecutive Sundays in the church and in front of the congregation announce that two of the parish´s members intend to marry. It was unfortunately only two weeks until had to leave, so Rose and I would not have time to get married in the church.

The priest I spoke with was a kind and understanding man, and on a piece of paper he wrote down a list with various suggestions about what to do. All his advice included the priest Kjell, meaning his own involvement. He wrote: "You have a civil marriage as soon as possible and Kjell joins you in holy matrimony when you come back; you marry within the Catholic Church in the Dominican Republic and Kjell consecrates you marriage with a Lutheran ceremony when you come back; get married in an Swedish embassy abroad and Kjell joins you in holy matrimony as soon as you come back," etc., he gave me at least three more alternatives.

Rose had a good laugh when I came back with the note, and we decided that I as rapidly as possible had to call the City Hall and ask if the mayor, or rather the municipal council´s chairman, could marry us before we left the country. Well, we could get married in time, provided that I presented them with a Certificate of No Impediment. The time for the ceremony could then be set to twelve o'clock on Saturday after two weeks. It was the day of our departure! If the wedding ceremony took place at noon, we would miss the flight. After talking to Rose, I called back to the Town Hall and asked if there was no other solution. Well, the day could not be changed, but the marriage could take place at ten o'clock instead of twelve. Whoa, with small marginal we would be able to catch the plane!

On the Friday before our departure we received a call from the City Hall. They wondered if all was ready for the wedding. Had we contacted the two witnesses? Witnesses? Did we need that? We had planned to make it all very discreet, without telling anyone about our marriage, not even my parents and sisters. After all, we had planned that Kjell was going marry us when we came back. It was now late afternoon and I had no other choice but to call my parents. Of course they were surprised, but certainly - they would drive down from Hässleholm early the next day, to witness the ceremony and then drive us to the hydrofoil to Copenhagen.

Everything was packed and ready when my mother and father rang on the door and we hurried down to the car. However, Rose who was busy with some research, had to go down to the Department to print a few copies which she had to bring with her to the Dominican Republic. While my mother and Rose ran up to the copier, I and my father waited behind in the car. The minutes passed, we were sitting there waiting with ever growing concern. When ten minutes were left until the wedding ceremony would take place, Rose and my mother came back running with the copies in their hands. As expected the copier had jammed and since it was Saturday no one had been around to fix it. Nevertheless, against all odds Rose had finally managed to find another machine that worked.

In haste we drew down to the City Hall. For some reason, the wedding ceremony would take place at a lower level and heading down there my Father hit his head and had to rest a few minutes on a chair to recover from the blow. The Municipal council´s chairman carefully prepared a table and placed himself cautiously behind it. Rose and I sat down in front of him while my parents placed themselves behind us. The minutes passed. Unwieldy the wedding officiant took a matchbox and began to light the candles of two candelabra. We were getting stressed out, Rose asked timidly:

- Is that really necessary? We are in a hurry.

The municipal council´s president nodded, smiled and explained that it was customary. Then he looked seriously at us, opened a book and began to read aloud:

"You want to marry each other. The marriage is based on love and trust. Through marriage you promise to respect and support each other. As spouses, you remain two independent individuals who will ... "

Rose interrupted him in a whisper:

- Do you really have to read all that? Will it take a long time? We thought that a civil marriage would be quick and easy.

The friendly man smiled patiently:

- Unfortunately, I have to do it, but I assure you ... it won´t take long.

And with the same calm voice, he continued to read:

"... who will gain strength from your bond. Since you have declared that you want to enter into marriage with each other, I ask: Do you ... "

When Rose and I had answered yes to his questions, the municipal president told us that it was time exchange rings. Rings? Did we need to bring rings? I didn´t know that. In haste we borrowed parents´ wedding rings and the officiant could finally declare us to be husband and wife. However, he was compelled to add a few more words:

"When you now enter life and go back to your routines, remember your desire for companionship, the love and the respect for each other you felt at the moment that brought you here. Let me wish you happiness and prosperity in your marriage. "

Beautiful words, but we had some trouble perceiving them, as time mercilessly ticked on. We thanked sincerely the friendly, but slightly bewildered man, rushed up the stairs, into the car and drove quickly to Malmö and the hydrofoils. We managed to get to the check-in counter on time and because we obviously looked happy and newlyweds Rose was allowed to bring her bridal bouquet into the aircraft. We have now been married for thirty-five years, but were never wedded by Kjell.

On the flight I took out the parcel Sverker had given me. It was a gift-rapped book I was going to bring Mikhail Bogin. Sverker had told me that he once had worked as assistant and interpreter for Bogin while he was in Sweden and prepared the filming of The Man from the Other Side. What I know Sverker is quite fluent in English, French, Russian and Icelandic, and probably also speaks some other language.

I've never been quite clear about what happened to Bogin after he had been removed as director for The Man from the Other Side. He traveled back to the Soviet Union and in 1972 he made yet another movie Ischu Chelovka, which apparently also was called something like I seek my own and was based on true-life stories about separation and meetings, about Russians seeking for loved ones lost in the war. However, I cannot find other than Russian references to that movie. I understand that it was shown in the US and at that time Bogin chose to seek asylum there. The parcel Sverker had given me had between its gift bands an envelope inserted with Bogin´s address in New York.

We would be a week's time in New York, before we were going to one of Roses sisters who lived in Puerto Rico. Rose had previously lived in New York and knew the city quite well, to me it should be unfamiliar but after all the movies I've seen, it seemed strangely familiar. After one day, we called Mikhail Bogin who invited us home to his apartment on Manhattan. It was high up and had a breathtaking view of nighttime Manhattan. He greeted us cordially and I think he invited us to dinner at home, but I don´t remember. However, I remember how moved he was when I gave him Sverker's gift, which turned out to be a book in Russian. Bogin thanked us effusively and asked:

- How is Sverker doing? Has he enough to survive?

I assured him that was the case and wondered why he was concerned if Sverker would have a difficult time. Bogin replied in his perfect, but heavily accented English:

- Sverker is a unique fellow. Serious and calm, but he has a strong sense of humor. I remember when we were stuck in negotiations, there was a lot of hassle with that movie and emotions ran high. While we raised our voices Sverker sat leafing through a dictionary and apparently found a word. Suddenly he had all attention directed at him and we all fell silent. Sverker looked up from his book, in the unexpected silence he watched as seriously, one by one, before he stated in perfect Russian, slowly and very clearly: "You Russians seem to be very nervous people."

Bogin told me that his time in Sweden had been difficult for him, professionally and personally. However, he had appreciated Sweden, especially the peace and quiet. Poetically, he noted:

- Sweden is the only place where I have heard what it sounds like when the snow is falling.

For me this was a strange assessment, because when I think about Russia I tend to imagine a vast, desolate, snow covered expanse. Bogin told me that after he lost his appointment in Sweden he no longer felt at home in the Soviet Union and began to speculate what he could do to find asylum in the West. He grabbed the opportunity when he came to the United States, probably in connection with the display of his latest movie, Ischu Chelovka.

- They received me with open arms. I was not a well-known director, though some of the movie connoisseurs knew who I was. My first movie had won the FIPRESCI prize at the Moscow Film Festival and had been presented here in New York, where it got great reviews.

Then I did know anything about FIPRESCI, but now I have found out that the acronym stands for Fédération Internationale de la Presse Cinématographique, a prestigious international association of national organizations of professional film critics and journalists. Each year its representatives are present at festivals around the world and grant prizes to young, promising directors. The list of award winners is impressive, with names like Pedro Almódovar, Rainer Maria Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Woody Allen, Aki Kaurismäki, Roman Polanski. Andrei Tarkovsky and Wong Kar-wai.

- After my defection I received a lot of support and encouragement. What surprised me was that those who welcomed me were so happy to point out how much misery there was here in the US; violence, racism and poverty. They drove me around and showed me how miserably poor people lived. When I told them that such misery existed in the Soviet Union as well, they looked at me with surprise.

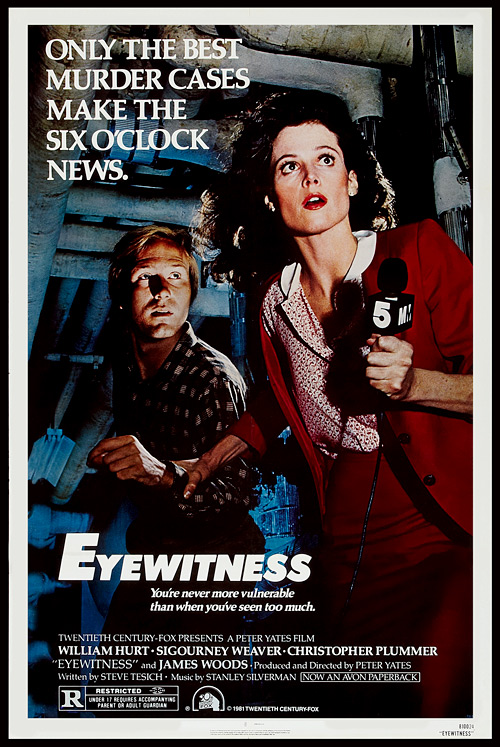

Bogin claimed he was pleased with how things had turned out for him since his arrival in the United States. He had not yet had an opportunity to shoot any movie of his own, but had recently been given a role in a movie with Christopher Plummer. It was called Eyewitness and would soon be premiered. I have not seen it. It was made by Peter Yates, who had become a cult director in the sixties due to Bullitt, mother of all car chases.

As I confessed, I do not remember if we got any dinner, but I remember that Bogin offered us plenty of vodka and pickled cucumbers. Rose, who was tired after the trip and tumultuous events soon fell asleep on a couch, while I and Bogin watched TV, munched cucumbers and toasted one another. The TV presented a program about Line Dancing, people with big cowboy hats jumped coordinated about to country music. Bogin laughed heartily:

- Look at that! It´s wonderful! So American, so care free, so crazy and uniform.

Uniformity was a theme Bogin had raised earlier in the evening and what he told us have stayed with me ever since.

- What amazed me the most when I came here and tried to establish myself after my first feeling of relief and surprise, was how regimented everything was. I began to believe that I have ended up in a socialist utopia. Everything was so unreal, so absurd.

- But the US is hardly socialist?

- Exactly! And that was why I came here. I assumed people would be different. I suspect that each and every one likes to be an independent and free individual. That we all like to form our own and genuine opinions about things. But, I found exactly the opposite - a socialist Utopia.

- In what way?

- At first I lived in a residential neighborhood outside of Manhattan, but I could not stand it there. That's why I moved here. Up there all was the same. The lawns looked alike, all well-kept. Even the houses looked alike, inside and out. People wore the same clothes, had similar cars, similar dogs and identical opinions. At the same time they claimed that they were all different and they felt sorry for me, a poor Russian fellow who had arrived from a Communist country where everyone had to do the same things, consume the same products, eat the same food, drinking the same liquor and think like the State commands. In vain I tried to explain that there are few Russians who have the same opinions, except that they do not like the Government. The Americans told me that they did not like Government, yet they believed that they lived in the best country of the world and had the world's best political system. It would be hard to find a Russian who honestly believes his country has the best political system in the world.

Bogin refilled the vodka glasses:

- My neighbors told me that the US is filled with injustice, yet they believed their nation has the best health care, the world's best scientists and artists. They are best in everything. Would a Russian say that about himself and his country? Not likely, at least not if he is an honest man. The Americans honestly believe themselves to be free and different. No Russian would believe himself to be free - but different? Russians do not have the same wife, the same dog and the same views. They do not read the same newspapers, the same books and would seldom agree about everything. They do not live in the best country in the world and they do not trust one another. You know, the US has not had any war within their borders, at least not since 1865. Sure, Americans have died and been killed in wars, but not common people, only their soldiers. The average American does not know war, starvation and hell and that is the reason to why they believe in themselves and their country. And they may be right. It is quite possible that they live in the best country of the world. But they want you to agree with them, even when you think they are wrong, at the same time as they want you to love their nation in the same way as they do. There is the problem of this nation.

- Are you not exaggerating?

- Of course I am. I am not talking about individuals. I'm talking about the system. I'm generalizing. I´m talking politics, just as we Europeans use to do among ourselves. Americans don´t understand politics, but they are masters of entertainment. Watch New York. Garbage collection does not function in this town. At least not in winter. As soon as it snows a little the entire town is in panic. Refuse trucks are remade into snow-ploughing vehicles and the piles of black garbage bags grow into Chinese walls along the sidewalks. Americans prefer to concentrate on one thing at a time - a celebrity murder, a divorce, a species of owl that´s dying out. They do not like to occupy themselves with two issues at a time. The shop down here on the corner is robbed once a week, but if I have my car standing outside in the street it has a parking ticket glued to it after two minutes.

He laughed and glanced towards the TV:

- What works well is the entertainment industry. Broadway is amazing. What magnificent shows, the coordination, the professionalism! They do brilliant show business of everything. They exterminated the Indians, but have made excellent entertainment out of that genocide. Everyone loves westerns. They lost the Vietnam War, but after the recent action movies young Americans believe that the Marines won the war. They have their superheroes and they seem to believe in them. We Russians have our super workers, but no one believes that they exist. The Americans have frightening violence statistics, but are doing exciting gangster movies of the misery. They are world champions of propaganda. They know that propaganda is show, myth and falsehood, and they are not ashamed of it. The Russians have everything to learn from them. Our propaganda is also an outright lie also, but it is not exciting, funny and entertaining. Sure, Soviet propaganda may be laughable, but then it is due its ridiculous ineptness. Americans are willing to believe in almost anything, but not Russians. Americans believe in success and democracy, not the Russians. Americans are deeply religious, they are basically religious. And frankly - that's why I love America. It's an ideal society for an artist and dreamer.

- But what you said about the US does not sound particularly liberating to me.

- No, no, but it´s the paradox that´s stimulating. The chimera that makes you want to change things, make a difference, show alternatives … and you know it´s possible to do so. Here it is, at least in principle, allowed to be different, to seek change, but at the same time you meet resistance. In a way, it would probably be almost as uncomfortable to go against conventional wisdom here as it is in the USSR.

- How?

Bogin swallowed his vodka and put down his glass:

- When I spoke to my neighbors and suggested what I thought was remarkable about this country ... that people had the same wife, the same poodle, the same car and the same opinions, they could get very annoyed and tell me that I was an incorrigible Communist and had no right to be in this wonderful country and criticize their democracy and freedom. Someone with my views ought go back where I came from and continue to support censorship, inequality and dictatorship. They could not understand when I tried to explain that I admired their democracy, that I loved the US. That I appreciated their country more than my own fatherland. The whole thing was schizophrenic because they often emphasized what they thought was wrong in the US; poverty, violence, racism, taxes and a lot of other things, which I frankly thought was not much worse than what I had experienced while living in the USSR. Wherever you are, it's not easy to be a stranger, a foreigner.

I had become tired and drunk. Words were merging, becoming blurred and I cannot remember everything Bogin told us, though the general feeling remains. I have often thought about what I imagine he said. Meeting with an exiled Russian during one of my first evenings in the United States has for the good and the bad colored my view of the country, and life in general. Several years later, we came to live for several years in New York, where I thrived and I came to love the city.

I do not know how it's been for Bogin. Here in Rome, I have searched for him online. It seems that Ischu Chelovka was his last movie and his supporting role in Eyewitness his last film role. He apparently remained in New York. When I meet Sverker I will ask him if he knows anything about the fate of Bogin.

Online I found the final scene from his film Двое, Two, or as it is also called a Ballad of Love with which he won the FIPRESCI prize in 1965. It is about a young musician who courts a beautiful woman, who refuses to answer anything he tells her, even though they meet several times. It turns out that she is deaf. They fall in love and their love becomes a silent love. New York Times critic Howard Thompson wrote:

See "A Ballad of Love," whatever you do. It was made at the Riga Studios in Latvia, under a young director of uncommon skill and insight named Mikhail Bogin, who wrote the screenplay with Yuri Chulyukin. Ever so simply and sweetly, minus one drop of saccharine, the picture conveys the growing love of the spirited oboist and the beautiful girl in her silent world who studies at a pantomime theater for deaf mutes.

"What is music like?" she scribbles. There is a moment of freezing beauty with the boy watching the girl as the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet is pantomimed on the stage. The picture is most effective when the sound track goes silent, as at the climax when the deaf girl attends a concert.

The film clips off abruptly. If only it could have gone on and on.

I hope to see Bogin´s movies and fear that he is one of the many artists who have been forgotten and not gotten a chance to develop their great talent and received the fame they earn. One of the many who for a short time had their moment of glory. Opportunities came, but in the wrong place, at the wrong time, in the wrong context. Bogin had to deal the shapeless colossus of The Man from the Other Side. He was given compassion and support in the US, got to act in a major movie, yet he slipped out of the competition, his great capacity was not taken care of. It is not often that we end up in a fairy tale like the one Radu Mihăileanu presents us with in his Le Concert – in which human warmth, combined with artistic mastery, overcomes all obstacles and everything comes to a happy ending.

Figes, Orlando (1997) A People´s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891 - 1924. London: Pimlico. Pipes. Richard (1995) Russia under the Bolshevik regime 1919–1924, London: Vintage. Thompson, Howard (1966) "Screen: 2 Soviet Works: ´Father of a Soldier´ is with ´Ballad of Love´," in The New York Times, February 21. The last scene in Bogin´s movie A Ballad of Love: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u5yaOSKKiHI

.jpg)