ALIEN OF THE SEAS: The multifaceted octopus

It became a lengthy blog post and a parable is at hand – it seems as if I had been seized by an octopuses’ sucker-covered tentacles and unable to offer any resistance was dragged down into the depths of a sea of stories. It was difficult to get out of it all. When I finally have surfaced again, I realize that down there I found so much more than could be contained within the text below.

A walk through central Rome stimulates the imagination, trapdoors open up, leading down to forgotten history. Shortly after I finished writing my previous blog post about Victor Hugo and The Toilers of the Sea, I ended up in Piazza Navona. Standing by a fountain depicting how Neptune fights an octopus, I came to think about Hugo’s novel and Gilliatt’s fight against with the sucker equipped monster. However, could that story really have been an inspiration for such an old sculpture? I asked an Italian friend of mine if he knew who had created the fountain. Like so many others, he replied that it must have been Bernini, the master who made the magnificent fountain in the middle of the square. It did not sound right, to me. The octopus fight was well done, but it did not “feel” like a Bernini sculpture.

After returning home, I visited Wikipedia and … the so-called Neptune Fountain had been completed in 1878, more than 250 years after Bernini in 1651 had created his obelisk-decorated Fontana dei Quattro Fiumi, Four Rivers Fountain. Since 1570, what is now the Neptune Fountain had been a basin used as a source of drinking water and for washing clothes.

It was not until the beginning of 1870 that the Sicilian sculptor Gregorio Zappalà turned it into a fountain and along the edge created baroque-inspired nereids, cupids and seahorses. In 1878, the fountain was crowned with Neptune’s octopus fight battle, made by the Roman sculptor Antonio della Bitta, about whom I have not been able to find any information. Accordingly, it would not be impossible that this della Bitta had been inspired by Hugo’s portrayal of Gilliatt's struggle with Le Piuevre. After being published in 1866, The Toliers of the Sea immediately became an international success. In Italy as in the rest of the world, the bad reputation of the octopus was permanented as a predatory monster attacking and feeding on humans.

The octopus had long before that, throughout the Mediterranean, been a well-known creature, both admired and feared. Already around 1400 BC we find the strange animal depicted on a number of pots and vases from Knossos and Mycenae. It was for certain considered to be a delicacy and became a model for monsters like Hydra, Scylla and Medusa.

.jpg)

The intelligent mollusk was also a symbol of smart activities and widespread influence. After all, it consisted almost entirely of a head and eight constantly active tentacles. This remarkable constitution made the octopus appear on Greek coins, such as the one below from the Greek colony of Syracuse on Sicily.

A Pompeian floor mosaic accurately depicts the octopus as a predator capable of attacking and cracking the shell of larger and complicated prey, like a lobster. Recent research has found that the strange mollusk, unlike a large number of other creatures, also is capable of using tools, for example stones to break mussel shells. In the Pacific Ocean, the octopus might seek out and carry away broken coconut shells, which that it use to build nests and hide itself from other predators.

.jpg)

Appropriately, the Pompeian octopus adorns the cover of Natural History: A Selection by Pliny the Elder, which I like to botanize in. A delightfully crazy, encyclopedic, all-encompassing “natural” history from the first century AD.

The knowledgeable, well-informed and sometimes wildly fabling Pliny the Elder wrote quite a lot about the marvelous octopus; its great adaptability, ability to change colour and astonishing intelligence. However, just like Victor Hugo, who may of course have been inspired by Pliny, the Roman writer incorrectly describes the great mollusk as a predator that tends to attack humans, kill and eat them:

… no animal is more savage in killing a man in the water: it struggles with him, embracing him with its tentacles, swallows him with its many suckers and pulls him apart, it attacks shipwrecked men or men who are diving.

Even though huge variants of such a monster did not often occur in the Mediterranean, Pliny knew how to tell that there were unusually large octopuses there. According to him, Emperor Augustus' good friend Lucullus had been presented with an octopus which head was the size of a barrel capable of holding 400 litres of water, its tentacles were nearly nine meters long, while the beast weighed 315 kilograms.

After looking at the Fountain of Neptune, I walked down Via dei Lorenesi, turned left onto Largo Febo, and followed a parallel street of Piazza Navona to Santa Maria dell’Anima, the main church for the German Catholic congregation in Rome.

A church, filled with art treasures, even a hint of the short span of European history when the Swedish Baltic Sea Empire was in the spotlight of Italian intelligentsia. Not far from the high altar of Santa Maria dell’Anima we find stately tomb monument of the Swedish brothers Magnus originally named Johan and Olof Månsson), equipped with magnificent baroque decorations and an impressive skeleton which in a bony grip carries Archbishop Olaus’ picture medallion.

All roads lead to Rome. Standing in front of the grave monument, I was a Swede caught by a feeling of slight dizziness. I was, as so often before in Rome, looking down into a historical abyss where by chance, reading fruits and personal thoughts became united into an almost incomprehensible unity. I had not expected to find in the German Church the brothers Magnus memorial, at least after just around the corner watching the fight against an octopus. In a strange way, the Magnus brothers connect Sweden with Rome and not the least with astounding octopus-like monsters.

Let me take the Swedish connection first. How did two Swedish archbishops end up in Rome? In 1512, Sweden was part of union with Denmark and Norway. The common kingdom was generally ruled by a Danish king. However, some Swedish nobles were dissatisfied with the arrangement. They wanted to break away from the pact and elect their own king. Leading member of this group was the Riksföreståndare, satrap, Sten Sture the Younger and it was he who sent the erudite, young priest Johan Månsson to the Pope in Rome. This was done on the advice of the Swedish archbishop Gustav Trolle, who in Rome had been installed in his office by none other than the Pope himself. Since then, Gustav Trolle considered Pope Julius II as a personal acquaintance and this was the reason why Johan Månsson, now with the Latinized name Johannes Magnus, was sent to Rome. Julius II was a adroit and aggressive politician who waged war on several fronts, including against France, while he with an iron fist defended his Church State against any foreign intrusion.

Unfortunately, Kristian, who a year after Johannes Magnus’ arrival in Rome under the name Kristian II, in Sweden called Kristian The Tyrant, had become king of the Nordic Union. Kristian already had better cards on hand than Sten Sture, the Dane had namely close contacts with the Pope’s most powerful ally – the German-Roman emperor and in 1515 Kristian II married Carlos de Habsburg’s sister, Isabella. After his grandfather Maximilian I, Carlos eventually become German-Roman emperor in 1519. Both the emperor and the pope were well aware of the fact they were forging schemes against the emperor and the papacy.

Sten Sture the Younger sent the scholar Johannes Magnus to Rome as part of a PR drive that intended to increase Sweden’s importance while diminishing Denmark’s influence among the papal courtiers. Johannes had through his research found that Sweden was the country of origin of the Goths, a mighty tribe of warriors who once had defeated the mighty Rome, as well as conquering large parts of Europe. Eventually the Goths had become devoted defenders of the True Christian Faith. According to Johannes Magnus the Goths’ Swedish descendants had remained faithful upholders of the pure doctrinal Catholicism of the Papacy and thus worthy of replacing the Danes as the rightful rulers over all the Nordic countries. Unfortunately, Johannes Magnus’ shaky argumentation for Swedish superiority did not convince Julius II, who died the year after Johannes’ arrival, though the Swedish prelate remained in Rome with the intention of trying to convince the new pope, Leo X, with his arguments about the Swedes’ preeminence, at least if compared to their Nordic neighbours.

After Sten Sture’s death three years after Johannes Magnus’ arrival in Rome, Christian II attacked Sweden, subdued his enemies and union breakers and was crowned king in Stockholm. Shortly after the three-day coronation party, Bishop Trolle, who had anointed Christian II, demanded compensation for his castle Stäket, which Sten Sture had attacked and burned down, after he rightly, assumed that Trolle had joined Kristian II’s union party. Under Kristian II's supervision, Bishop Trolle saw to it that rebellious and “untrustworthy” priests and nobles, who had sided with Sten Sture, were sentenced to death for heresy.

One week after the coronation festivities, the executions began at Stortorget, just below the royal palace. Even he nobles’ servants were also executed with sword and gallows. A total of 84 people fell victim to what came to be called Stockholm’s Bloodbath. The corpses were burned at piles on Södermalm, just outside the city gates. Sten Sture the Younger’s grave was dug up and his cadaver thrown into the fire. Johannes Magnus’ brother Olof was witness to all this.

After ten years in Rome, Johannes Magnus dared to return to Stockholm, where Gustav Vasa now had become king after Sweden had broken away from the union with Denmark an Norway. Gustav Vasa had offered Johannes to become Sweden’s new archbishop, but he considered it to be an overly dangerous position, especially considering that a small but influential group of priests, trained by Martin Luther in Wittenberg, now had the king’s ear and recommended a break with the Pope and offered Sweden’s new and autocratic ruler to become dictator of the Church as well.

On a diplomatic mission in Danzig (he was to find a wife in Gustav Vasa) Johannes chose to stay abroad. His two-year-younger brother Olof, who now called himself Olaus Magnus, was soon reunited with him. Like his brother, Olaus was also a learned man. In Sweden he found himself in a vulnerable position after making himself known as a convinced supporter of the papacy. Furthermore, he had on behalf of the Catholic Church traveled all over Scandinavia, selling indulgences. He had even for a time been living the Sami in northern Sweden.

For several years he brothers lived in Danzig, unsure if they could venture down to Rome. Johannes Magnus had not been undivided critical of Lutheranism and had furthermore been a fierce opponent to the introduction of the Inquisition in Sweden. Eventually, the brothers dared to travel up in Rome, where they were warmly welcomed by the Pope, hoping that they could be instrumental in winning Sweden back to the Catholic faith. When Johannes died in 1544, the pope appointed Olaus as archbishop of Sweden. It was a useless maneuver since the Lutherans by now had a strong grip on Gustav Vasa’s kingdom and Olaus never returned to his homeland.

In 1557, Olaus Magnus died in Rome, he had until the day of his death tirelessly been working on creating revolutionary and attractive impression of his previously internationally relatively unknown homeland. In several books he had described a fantastic, mysterious and basically wealthy nation. At first he published letters and pamphlets while propagating for his brother’s extensive volume Historia de omnibus Gothorum Sveonumque regibus, The Story of All the Kings of Gothia and Sweden, written in clear and flawless Latin. The book became a bestseller and Olaus made sure that it ended up with Gustav Vasa’s sons.

Johannes Magnus had created comprehensive lists and detailed descriptions of members of Swedish royalty, all the way back to one of Noah's son, who according to him was called Magog and actually had been king of the Swedes, or Goths as he called them. In a similar vein he continued to tell tall tales composing wild and often quite funny fables, with one or two elements of proper reading fruits. Several of the kings he wrote stories about were of course Johannes’ own inventions. However, Gustav Vasa’s sons became firm believers in Johannes Magnus’ concoction and this belief was the reason to why they, as Erik XIV and Karl IX, adopted such high order numbers.

Olaus Magnus did not content himself only with spreading knowledge about Sweden’s marvelous history, he also spread, in the same fantastically fabulous spirit as his brother, knowledge about Sweden’s geography and wonderful history.

During their exile in Danzig, Johannes and Olaus had by the the Portuguese historian and geographer Damião de Góis been emboldened to write about their homeland and were in this endeavor financially supported by Johannes Dantiscus, a wealthy diplomat and poet, closely associated with Sigismund I, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania. These men assumed that the Magnus brothers in the Nordic countries could contribute to a strengthening of the position of Catholicism. These influential potentates gave them access to books and manuscripts and were very interested in Olaus’ stories about his own travels up in the far North. After ten years in Danzig, the Magnus brothers went to Venice and in 1539 had their great map of Nordic countries published by a famous Venetian master printer.

The map is certainly a masterpiece. It is the earliest reasonably accurate map of the Nordic and Baltic countries, with accurate indications of cities, villages and geographical landmarks. In addition, the map was lavishly illustrated, not the least with imaginative sea monsters, something that made the Italians describe it as Mappa Marina, the Sea Map.

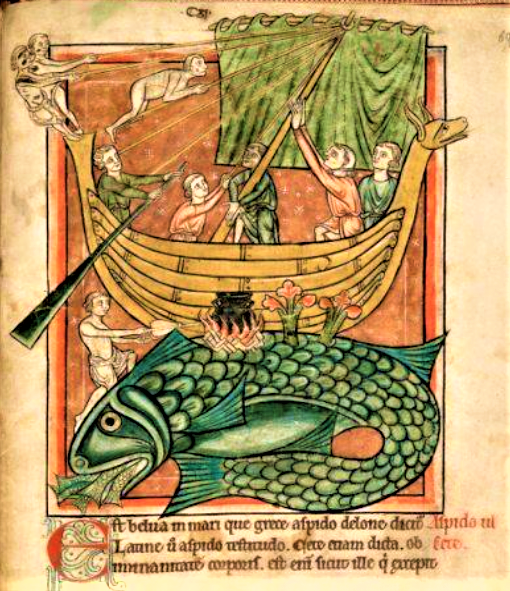

Above Lofoten, we glimpse the monster that became associated with Olaus Magnus – a depiction of the legendary Kraken, a giant octopus wonder capable of devouring entire ships. Two years before his death in 1555, Olaus Magnus was able to publish, in the same flawless Latin as his brother, a huge work which initially had been intended to be a complement to Mappa Marina, though over the years it grew in scope.

In the preface to his work, Olaus Magnus emphasized his purpose of providing the educated readership with a

history about the Nordic peoples, their different conditions, customs, leisure activities, social conditions and their specific way of life. Their wars, buildings and tools, mines and other wonderful things, as well as descriptions of almost every animal living in the Nordic countries, being part of their nature. A work with a variety of knowledge, partly illuminated through foreign examples and partly with depictions of domestic things, to a large extent suitable for entertainment and a pleasure to read, for certain it will amuse and stimulate the reader’s mind.

Magnus’ extensive description of Nordic ways was the result of more than thirty-five years of hard work and is filled with the sheer joy of telling stories. A mixture of short reflections and stories based on his own youthful experiences, tall tales, reading fruits and pure fantasies,which in spite of a lot of nonsense actually contains a core of truth. The whole thing becomes a peculiar reading experience, augmented by strange images which are a mix of everything possible. It is almost impossible to read the work from cover to cover, but it is a pleasure to randomly read a paragraph or two in this remarkable book.

An example, among thousands of others, of the work’s idiosyncratic character is when Olaus Magnus came up with the idea of carefully trying to describe snowflakes. The lack of literary and artistic precursors becomes noticeable when Olaus Magnus draws our attention to hitherto unsubscribed phenomena. He writes about the “changing forms of snow” and then gets involved in a number of attempts to describe what snow really looks like, referring to Aristotle, chemistry and his own observations, and writes among other things:

it is obvious for people everywhere and especially in the Nordic countries, as well as neighbouring areas, to have an opportunity to perceive the variety of wonderful shapes and images of snow […] one may admire these phenomena rather than try to explore the reason to why and in what way so many forms and images might occur. It is beyond any artist’s creative ability to portray such soft and insignificant things. It is actually not uncommon to see 15 or 20, or sometimes even more, different shapes of snow and ice. At times, changing patterns appear on glass panes, which in order to exclude the cold are applied over window openings of heated cabins, and one might thus have the opportunity to appreciate how through the influence of the external cold and the wonderful art of nature, the glass becomes adorned with changing images that an artist, any one, at the sight of it may rather admire the glory of nature than imitate it.

The difficulty of describing something well-known, which nevertheless has never been described before, permeates the entire Olaus book, or rather books – his work about the Nordic peoples was published in thirteen volumes. The difficulties of depicting unknown things to the public are also noticeable in the images of the unknown illustrators, which accompany Magnus’ text. The artists apparently did not know first-hand what they were trying to portray. They were forced to build on what they knew and what Magnus had told them. Accordingly, turned to the work of other artists and took theses depictions as models for what they were trying to convey. For example, when they try to portray Swedish hospitality, which Olaus Magnus of course says is very generous, though according to him it had certain limitations – Russians, Muscovites and Danes generally smelled so bad that you could not keep them in your house for a longer time – so could for example, an artist working for Olaus Magnus make use of a woodcut by Hans Holbein the Younger.

Just as Olaus Magnus constantly combined his descriptions with information taken from the writings of Pliny the Elder and Aristotle, the artists’ imagery also appears as a form of collage reminiscent of those found in contemporary manuscripts. where it occasionally happened that authors cut out pictures from books, pasted them in their manuscripts and occasionally pieced together parts from various other pictures. An approach made possible by how the art of printing had revolutionized art and literature.

When Olaus Magnus described one of his sea monsters, it became a kind of collage. He did for example portray a wondrous “fish”, which on his map is reproduced north of Lofoten, as if it was composed of different parts:

Off the coasts of Norway, or in the sea around it, there are monstrous fish. They have unusual names and reputed to be a kind of whales, who show their cruelty at first sight, and thus make men afraid to see them; and if men look long enough upon them, they will fright and amaze them. Their forms are horrible, their heads square, all set with prickles, and sharp and long horns around them, resembling the roots of an uprooted tree. Such a head is 10 to 12 cubits in circumference. The eye’s pupil is a cubit wide, scarlet in colour. When it is dark, the fishermen can in the distance see how it shines among the waves like a blazing fire. Its hairs resemble goose feathers, are dense and long and look like a drooping beard. The rest of the body, on the other hand, is very small in comparison with the square head, certainly not exceeding 14 – 15 cubits in length. One of these sea-monsters will easily drown many great ships provided with strong mariners.

.jpg)

The illustrator has fairly accurately reproduced Olaus Magnus’ description of the beast. The thorns around the head, the big eyes and the elongated body have led many to assume that this is not a kind of fish or whale, but rather a giant squid.

Several of Magnus’ imaginatively described and illustrated sea creatures have, on closer inspection, turned out to be fairly accurate descriptions of real mammals and fish. Magnus’ Sea Unicorn could thus be a narwhal – Olaus Magnus was well aware of the fact that“unicorn horns” exposed in churches and cabinets of curiosities were in fact narwhal teeth, though he nevertheless called the animal Sea Unicorn. The Pristern is obviously a sperm whale, while The Polyp, which in the picture in Olaus Magnus’ book looks like a lobster, is in the text quite correctly provided with eight arms equipped with suckers and described as feeding on fish and mussels, laying eggs and able to adapt both body and colour to its environment. Completely erroneously, however, Olaus Magnus, like his so often quoted Pliny the Elder, believed that The Polyp, or more correctly the octopus, was a predator attacking and killing humans. Quite correctly, however, both Pliny and Magnus assumed that the whale described as being as large as an island, was in fact a Blue Whale. What Olaus Magnus named as Ziphius is an orca and he refers to the walrus alternately as “Sea Pig”, “Sea Cow” or Rosmarus, while quite correctly mentioning that its tusks are used to carve chess pieces.

Olaus Magnus’ books became a success and Latin editions were printed in several of Europe's major cities. In Amsterdam and Antwerp they were reprinted several times. The famous epic poet Torquato Tasso was in Ferrara one of many who were fascinated by the brothers Magnus’ tales about Nordic peoples and based his verse drama, Galeato Re di Norvega, on the brothers’ stories. The plot was inspired by Johannes Magnus’ tales about Scandinavian kings, while environmental descriptions reflect Olaus Magnus’ fanciful narrative. Tasso later reworked his drama and named it Torrismondo. Tasso's lover, Orazio Ariosto, grandson of the great poet Ludovico Ariosto, wrote in his grandfather’s style an extensive unfinished work about the Icelander Alfeo, a tale which was also based on the writings of the brothers Magnus. Through Olaus Magnus’ books, the mysterious and cold Nordic regions became attractive to romantically inclined poets such as Lasso and Ariosto. Russia’s National Library preserves an edition of Olaus Historia de gentibus septenrionalibus filled with Torquato Tasso's handwritten marginal notes.

However, it was not primarily poets and historians who became fascinated by Olaus Magnus’ books, but zoologists and natural scientists. Ullisse Aldrovandi (1522-1605), a physician and naturalist whom Carl von Linné considered as originator of the scientific exploration of nature, published several books on healing herbs, birds, insects and fish, much more skillfully and realistically illustrated than Olaus Magnus’ books.

In his old age, Aldrovandi wrote a book he called Monstrorum historia cum Paralipomenis historiae omnium animalium, a description of monsters illustrated with examples from the entire animal kingdom, in which he, after being inspired by his studies of freaks of nature and fish, listed and depicted monstrous creatures from the animal as well as legendary tales about misshapen humans. The excellent illustrations provide detailed representations of animals that Aldrovandi and others had seen and were able to describe in a fairly correct manner. However, for more rare or legendary creatures he occasionally used images inspired by Olaus Magnus, like the narwhal that can be viewed under a realistically rendered shark.

Like Olaus Magnus and his illustrators, Aldrovandi created monsters by combining different models and creatures.

Contemporary with Aldrovandi was the Swiss Conrad Gessner (1516-1565) who published an equally lavishly illustrated Historia animalium, The History of Animals, in five volumes with more than 4,500 illustrated pages. His octopus is for example as true to nature and as skillfully depicted as the one found by Aldrovandi.

But, when Gessner ventured to describe and depict wondrous sea creatures, he was like Aldrovandi inspired by Olaus Magnus.

By the middle of the 17th century, a priest, Francesco Negri (1623-1698), became in Ravenna immersed in Olaus Magnus’ books about the Nordic countries and seized by an urge to visit the strange places that the Swedish bishop had described in such a vivid manner. Between 1663 and 1666 Negri traveled alone through Sweden, Finland and Norway. Negri’s Viaggio Settentrionale, Nordic Journey, was published just after his death. The book relates what he has seen, heard and experienced in the distant north. During his travels, Francesco Negri could confirm some of Olaus Magnus’ tales and observations, though he admits that much of what the Swede wrote was exaggerated of distorted.

Like Olaus, Negri also had difficulties in finding the right words and comparisons to describe what he had witnessed, like the northern lights and strange animals, including a stranded, rotting whale he was confronted with on the Norwegian coast. Like Olaus Magnus, Negri spent some time with the Sami, whom he considered to be the “happiest people on earth”, liberated as they were from other needs and values than those they encountered during their ”perfect nomadic life”. Despite his priesthood, there is no preaching nor any intents of proselytizing in Negri’s book, he demonstrates an open curiosity about everything and everyone he encounters. Negri’s book is not illustrated, though his preserved notebooks have several drawings, quite peculiar is for example his inability to draw spruces, even if he had them right in front of him they became a kind of strange palm trees.

Negri is the first one to mention Kraken by name, he calls it Sciu-crak and writes that he has heard Norwegian fishermen tell him about

a fish of immeasurable size, with a flat, round figure, with many horns or arms at its ends, with which it hugs the fishermen's boats from all sides... very slowly he rises from the depths of the sea and with his backside he touches the boat, which he soon afterwards squeezes to smithereens.

By Negri, Kraken definitely appears as some kind of octopus and even more so by Erik Pontoppidan the Younger (1698-1764) He was a Danish theologian, historian, fiction writer, entomologist and ornithologist who from 1746 to 1754 served as bishop in the Norwegian seaside town Bergen, where he wrote Forste Forsorg paa Norges Naturlige Historie, A First Attempt to Describe Norway’s Natural History, which in 1753 was published in Copenhagen.

.jpg)

.jpg)

In his extensive work, Pontoppidan devoted several pages to the Kraken, which he had heard described by fishermen and other seafarers. According to Pontoppidan, the Kraken is “the largest sea monster in the world. It is round and flat and full of arms or branches.” He adds that the beast seems to have been endowed with a capacity to colour the water around it with a black secretion. Large as a floating island, its huge arms can reach the tops of a warship’s masts and drag it into the depths. It lives several hundred metres below the sea surface, but may occasionally rise up from the depths. When fishermen became aware of a slowly ascending, enormous shadow under the waves, they knew that the Kraken was surfacing and had to hurry away from the place, because the enormous size of the animal might make boats capsize by causing huge wide vortices able to carry ships down deep into the depths.

.jpg)

A jocular summary of Kraken lore, spiced with some new information, is provided in Jacob Wallenberg’s cheerful travelogue Min son på galejan, or more exactly My Son on the Galley, An East Indian Voyage Containing All Kinds of Ink-horn Fancies, Collected Onboard the Ship Finland, Which Sailed from Gothenburg sometime in December 1769, and Returned There in June 1771. The voyage described by Wallenberg began rather unfortunate when the Swedish East India Company’s three-masted barque was forced to seek a port in Norway only after a day of sailing through a violent storm on the North Sea. In the Norwegian port it was decided to stock up the ship further and load additional timber for repairs. In the port, Jacob Wallenberg was by the Norwegian pilot told stories about the dreadful Kraken:

Kraken, also called the Crab-fish, which is not that huge, for heads and tails counted, he is no larger than our Öland [the second largest Swedish island - less than 16km]. He stays at the sea floor, constantly surrounded by innumerable small fishes, who serve as his food and are fed by him in return: for his meal, (if I remember correctly what E. Pontopiddan writes,) lasts no longer than three months, and another three months are then needed to digest it. His excrements nurture in the following an army of lesser fish, and for this reason, fishermen plumb after his resting place. Gradually, Kraken ascends to the surface, and when he is at ten to twelve fathoms, the boats had better move out of his vicinity, as he will shortly thereafter burst up, like a floating island, spurting water from his dreadful nostrils and making ring waves around him, which can reach many miles.

By Wallenberg we encounter a confusion between Kraken and ancient yarns about how sailors went ashore on what they thought was an island, but which eventually turns out to be the back of a huge whale. The earliest surviving evidence of this history is the Voyage of Saint Brendan the Abbot, journey of Abbot Saint Brendan, which was written down sometime in the seventh century, though the tale is earlier than that. It tells the story of how Brendan and his comrades dock at a barren, small island. They make a fire to grill their mutton,. Suddenly the ground begin yo shake beneath them. An earthquake! Terrified, the monks rush back to their ship and to their great surprise they watch how the whole island sail away with the fire still burning. Only the wise, old Saint Brendan remained calm, explaining that the island must have been a Jasconius, the Ocean’s biggest whale.

It is a well-known folk tale and is for example found in the popular Russian tale of Ivan and the humpbacked horse. In Arabian Nights, it appears in the story of Sinbad the Seafarer, where in several versions the mysterious island seems to turn into a giant octopus, rather than a whale.

.jpg)

As I now read these stories, I remember that Ivan and the Humpbacked Horse was one of my oldest daughter’s favorite fairy takes and I once decorated her birthday cake with pictures from the story.

When Janna was ten years old, she had a horrifying experience in New York that for several nights gave her nightmares. She and I had in New York visited The Irma and Paul Milstein’s Family Hall of Ocean Life at the American Museum of Natural History where a large diorama that shows how a sperm whale in the darkness of the depth of an ocean fights a squid made an indelible blow to the mind of my unusually imaginative daughter.

.jpg)

Possibly did Pierre Dénys de Monfort (1766-?) experience something similar when he had ended up standing in front of a votive plaque in Saint Thomas’ chapel in Saint-Malo, sometime by the end of the eighteenth century. With a commentary text, the votive painting had been placed in the chapel by grateful sailors after they had been miraculously rescued off the coast of Angola:

a sea monster of frightening size rose from the waves. It had already been seen gurgling in the distance and it now came up above the bridge deck, clinging to the ship, surrounding it with its long arms, agile and terrifying, reaching both sails and masts up to their full height.

At last, Monfort assumed he had found crucial evidence of his theory that huge squid lived in the depths of the sea and that these creatures were capable of sinking a ship. Skilled draftsman as he was, Monfort made a copy of the votive image, which since has become the epitome of the terrifying Kraken.

.jpg)

Monfort included the picture with several others in his work Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière des Mollusques, General and Detailed Account of the Mollusks, which was published in 1802 as an annex to a new edition by the great naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon’s Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière.

.jpg)

Monfort, who was born in the port city of Dunkirk had in a book by the linguist and medical doctor Franz Xavier Swediauer (1748-1824) read about how a captain of a whaling ship, “a sober and worthy man with common sense and known for his honesty” had told Swediauer that he in a sperm whale had found a partially gnawed, eight-meter-long tentacle. Eight meters! Monfort, who was known as a “shell researcher” and expert on mollusks, became immediately fired up and for a number of years he interviewed whalers who originating from the American ports of Nantucket and New Bedford used to dock in Dunkirk. Among others, captains “Ben Johnson” and a certain “Reynolds” assured Monfort several sperm whales killed by them had been marked by the tentacles of giant octopuses, and that half-rotten tentacles often had been found in their entrails. Monfort was also told that people traveling in canoes along the coasts of West Africa could be attacked by giant octopuses, which were called “demon fish” or “evil spirits” – ambazombi.

Monfort's enthusiasm and hasty conclusions became his downfall. In one of his writings, he claimed that ten English warships which had disappeared in the early 1780s for certain had been ensnared by giant octopuses and dragged down into the depths. It is somewhat strange that the otherwise well-informed Monfort appears to have been ignorant of the consequences of Hurricane San Calixto, which in 1780 swept across the Caribbean Antilles and caused the deaths of at least 22,000 people.

Due to unrest and fighting in connection with the American Revolutionary War, a number of British warships had been within and around the Caribbean Sea. During the hurricane that struck the area on October 9, 1780 and finally ebbed out on the twentieth of the same month, the HMS Phoenix and HMS Blanche frigates were sunk off the coast of Cuba. The frigates HMS Andromeda and HMS Laurel sank by Martinique, while the HMS Sandwich went under by Jamaica sank and HMS Egmont was wrecked on cliffs by St. Lucia. Further out to sea HMS Thunderer, HMS Stirling Castle, HMS Scarbourough, HMS Barbados, HMS Deal Castle, HMS Victor and HMS Endeavor disappeared leaving few survivors behind; Vice Admiral Peter Parker and Rear Admiral Joshua Rowley were drowned during the disaster.

For some reason, Monfort’s book ended up with the mighty British Admiralty, in charge of The Royal Navy. Its reaction was violent, how could an unnoticed little French snail scientist have the guts to claim that one of the worst disasters in the history of the mighty British Navy had been caused by enormous octopuses? How utterly ridiculous. The Admiralty’s angry dismissal of Monfort’s theory was spitefully quoted in Parisian newspapers and a generally scorned Montfort disappeared from sight, himself an obvious victim of giant octopuses.

When the mollusk researcher and geologist Gérard Paul Deshayes (1795-1875) as a young man in Paris visited a shell dealer, a drunk and miserably dressed man appeared carrying a bag filled with shell telling the shop owner that he thoroughly had studied, named and cataloged them. The shell dealer gave the ragamuffin a couple of banknotes and he disappeared. When Deshayes wondered who the strange man was, the trader had to his to his great surprise replied that it was the once highly respected Pierre Dénys de Monfort. The only other trace of Monfort’s sorry fate comes from the famous zoologist and paleontologist Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) who in a list of naturalists wrote that the “eccentric” Monfort had “on a street in Paris died of misery sometime around 1820 or 1821.”

A couple of years ago, when I had ended up in Saint-Malo, I searched in vain for Monfort’s votive image, but apparently there was no Saint Thomas’ chapel in the city. It was only afterwards that I found out that the chapel had been ruined during American bombings in August 1944, when 300 so-called Medium Bombers caused great damage to the old town during an attempt to drive out 70 German soldiers who stubbornly had put up a fierce resistance inside Saint-Malo.

Monfort had been quite right in his assumption that those who actually could provide valuable information about the mysterious giant squids were the American whalers. In his Moby Dick from 1851 Melville describes that while the hunting rowing boats had left the main ship and on the open sea was on the outlook for the giant White Whale, something strange and wondrous slowly emerges from the depths of the sea:

Almost forgetting for the moment all thoughts of Moby Dick, we now gazed at the most wondrous phenomenon which the secret seas have hitherto revealed to mankind. A vast pulpy mass, furlongs in length and breadth, of a glancing cream-color, lay floating on the water, innumerable long arms radiating from its centre, and curling and twisting like a nest of anacondas, as if blindly to catch at any hapless object within reach. No perceptible face or front did it have; no conceivable token of either sensation or instinct; but undulated there on the billows, an unearthly, formless, chance-like apparition of life.

As with a low sucking sound it slowly disappeared again, Starbuck still gazing at the agitated waters where it had sunk, with a wild voice exclaimed- “Almost rather had I seen Moby Dick and fought him, than to have seen thee, thou white ghost!”

“What was it, Sir?” said Flask.

“The great live squid, which, they say, few whale-ships ever beheld, and returned to their ports to tell of it.”

The almost aphasic and devotional scene in Moby Dick made remember an illustration in the comic magazine Prince Valiant, in which a craft with the same shape as a whaling boat, meaning that both the fore and aft are identical, encounters a giant squid:

.jpg)

Strangely mute, but nonetheless dramatic, is the fight between a sperm whale and a giant squid that which Frank T. Bullen describes in his autobiographical The Cruise of the “Cachalot” from 1898, which in my youth was one of my favourite books. As Bullen is on deck during a moonlit night-watch outside the coast of Sumatra, he witnesses a strange scene. Suddenly the still surface of the water became agitated:

Getting the night-glasses out of the cabin scuttle, where they were always hung in readiness, I focused them on the troubled spot, perfectly satisfied by a short examination that neither volcano nor earthquake had anything to do with what was going on; yet so vast were the forces engaged that I might well have been excused for my first supposition. A very large sperm whale was locked in deadly conflict with a cuttle-fish or squid, almost as large as himself, whose interminable tentacles seemed to enlace the whole of his great body. The head of the whale especially seemed a perfect net-work of writhing arms … naturally I suppose, for it appeared as if the whale had the tail part of the mollusk in his jaws, and, in a business-like, methodical way, was sawing through it. By the side of the black columnar head of the whale appeared the head of the great squid, as awful an object as one could well imagine even in a fevered dream. Judging as carefully as possible, I estimated it to be at least as large as one of our pipes, which contained three hundred and fifty gallons; but it may have been, and probably was, a good deal larger. The eyes were very remarkable from their size and blackness, which, contrasted with the livid whiteness of the head, made their appearance all the more striking. They were, at least, a foot I diameter, and, seen under such conditions, looked decidedly eerie and hobgoblin-like. All around the combatants were numerous sharks, like jackals round a lion, ready to share the feast, and apparently assisting in the destruction of the huge cephalopod. So the titanic struggle went on, in perfect silence as far as we were concerned, because, even had there been any noise, our distance from the scene of conflict would not have permitted us to hear it.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Eventually, science proved Monfort to be right – there were actually giant octopuses in the unknown depths of the oceans, although it was doubtful whether they were able to sink entire ships. In 1861, the two-masted, wheeled steamer Alecton was on its way across the Atlantic to French Guiana. Outside the Canary Islands, a large animal seemed to be floating on the sea surface. Several cannon shots were fired at what the captain assumed could be a giant squid, however the bullets did not seem to have any impact and the beast approached the ship. When the squid was right next to the ship’s hull, one of the crewmen managed to throw a harpoon at the monster. The harpoon entered deep into the back of the body and was attached to a strong rope. Despite the injured animal’s violent wringing back and forth, they began to winch it up and were able to attach a rope loop just under the tip of its spearhead-like tail. However, since the huge squid was twisting around so violently Commander Bouger ordered that the entire operation had to be aborted, fearing that the animal ”would damage the ship and injure the crew.” At that moment the squid was torn into two pieces and its lower part could be salvaged aboard the. When Alecton cocked at the port of Tenerife, the remains of the octopus could be thoroughly documented. It was a scientific sensation.

This event inspired Jules Verne to include a dramatic battle with a shoal of giant squids in his 1870 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas:

The Nautilus had then risen to the surface. One of the sailors, posted on the top ladderstep, unscrewed the bolts of the panels. But hardly were the screws loosened, when the panel rose with great violence, evidently drawn by the suckers of a pulp's arm. Immediately one of these arms slid like a serpent down the opening and twenty others were above. With one blow of the axe, Captain Nemo cut this formidable tentacle, that slid wriggling down the ladder. Just as we were pressing one on the other to reach the platform, two other arms, lashing the air, came down on the seaman placed before Captain Nemo and lifted him up with irresistible power […] The unhappy man, seized by the tentacle and fixed to the suckers, was balanced in the air at the caprice of this enormous trunk. He rattled in his throat, he was stifled, he cried, “Help! Help!” […] That heart-rendering cry! I shall hear it all my life. The unfortunate man was lost.

.jpg)

Just as Gilliatt's fight against the octopus raised concerns about how octopuses could attack individuals, Verne’s octopus fight inspired tales about even more extensive attacks of ever-larger sea monsters, a trend that reached its peak in the 1950s when nuclear fear created a multitude of mutated monsters, for example in the film It Came from Beneath the Sea from 1955, possibly inspired by a famous octopus fight in Disney’s film 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea which had premiered the year before.

.jpg)

Through extensive hydrogen bomb tests in its immediate habitat, a huge octopus had been driven out of its haunt in the almost 10,000 meter deep Mindanao Deep in addition it had become radioactive, something which made its natural prey avoid the enormous polyp, which through the radioactive radiation had become monstrously big. This colossal natural freak wonder instead began to attack ships to devour humans. Finally, the monster seeks refuge in San Francisco, after paralyzing the city in fear it is finally driven back into the ocean with the help of flamethrowers. Eventually is confronted with the film’s hero who from a submarine with a torpedo manages make a direct hit on one of the octopus’ eyes, the missile penetrates the beast, explodes and blows it to pieces.

.jpg)

It is quite possible thar It Came from Beneath the Sea also might have been inspired by the American author Howard Phillips Lovecraft's short story The Call of Cthulhu, from 1928, in which a huge aquatic creature that during millennia has slept on the bottom of the sea is awakened by an apocalyptic phenomenon caused by different celestial bodies placing themselves in a specific sequence. A similar event had long before humans appeared on earth made it possible for The Great Old Ones, enormous god-like forces from the depths of the Universe, to reach our planet. These primordial forces took no account of other creatures other than demanding worship from them so that the The Great Old Ones could be kept alive through dreams, human sacrifices and orgiastic rituals. Due to some unknown reason they had fallen asleep, though their hidden power over the evil urges continued to influence the brutish religions of “savages”.

A worldwide cult ensured that The Great Old Ones would one day be resurrected. A faith promoted by

low mix-blooded and mentally abhorrent types, who throughout animal fury and orgiastic license whipped themselves to daemonic heights by howls and squeaking ecstasies that tore and reverberated through those nightly woods like pestilential tempests from the gulfs of Hell.

Lovecraft (1890-1937) was for sure a tenacious racist and his descriptions” uncivilized” rites might be considered as a reflection of the lurid and contemptuous descriptions of the” barbaric” rites of fierce” savages” that European/American popular culture was soaked in at the time. A depiction of” undeveloped brutes” which was allowed to tinge mass media well into the 1960s and which and which harmful influence is far from obliterated from the minds of ”Westerners”.

In Lovecraft's short story, which takes place during his time, there are signs that the heavenly constellations are becoming arranged in such a way that soon will be awakened. Forced by recurrent nightmares, artistically gifted people begin to create images of ancient monsters, some of these artists eventually become insane, while in the bayous of Louisiana, in Haiti´s barren valleys, on the atolls in the South Seas and inaccessible hinterlands of Asia, idolaters are calling upon their cruel and ancient deities. Down by Antarctica, the Kingdom of The Great Old Ones – R’lyeh rising from the depths of the sea. In one of its vast burial chambers, the ruler of The Great Old Ones, Cthulhu, awakes from his multi-millennial slumber. A huge creature with a scaly humanoid body equipped with huge bat wings and an octopus-like head.

.jpg)

It is impossible to miss where Lovecraft took inspiration for its creation. He states that it is a contemporary tribe of ”degenerate Eskimos” which are praising Cthulhu as a god, something that has been discovered a ”rune researcher”. Runes do actually play a major role in Olaus Magnus’ history of the Nordic peoples. The one who eventually succeeds in destroying Cthulhu (temporarily, because the monster cannot die) is the Norwegian Gustaf Johanson, ”a sober and dignified man” who the narrator has been looking for in Oslo and Gothenburg, though his search was in vain because after his heroic deed Gustaf Johanson had been murdered by evil forces. This Nordic setting implies that Cthulhu is another variant of the Kraken, as the monster was depicted by Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892), a poet whose oeuvre Lovecraft was familiar with:

Below the thunders of the upper deep,

Far, far beneath in the abysmal sea,

His ancient, dreamless, uninvaded sleep

The Kraken sleepeth: faintest sunlights flee

About his shadowy sides; above him swell

Huge sponges of millennial growth and height;

And far away into the sickly light,

From many a wondrous grot and secret cell

Unnumbered and enormous polypi

Winnow with giant arms the slumbering green.

.jpg)

Cthulhus’ tentacled face may also have been inspired by works of art made by Lovecraft’s good friend Clark Ashton Smith (1893-1961). Ashton Smith wrote a number of short stories and novels based on Lovecroft's Cthulhu myths. Like Lovecraft, Ashton was fascinated by the dark, cold and mythical Nordic countries and wrote a series of novels set in Hyperborea, a legendary, Arctic continent which warmth and rich vegetation during the Pleistocene ice age are increasingly threatened by emerging ice masses. Several Cthulhu-like monsters live in Ashton’s Hyperborea, such as Abhoth, The Source of all Uncleanness, an abominable, dark gray, almost shapeless organism which constantly breeds ”malformations and abomination”. All sorts of obscene monsters crawl out of Ahoth's den. Several wander far and wide, but if any of them approaches their origin , Abhoth seizes it with his tentacles and devours it, as does the beast with every other creature that approaches its repugnant nest.

Like Cthulhu, the pirate ghost Davy Jones in the film Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest from 2006, has a horrifying, tentacled face. It is Davy Jones who in the film’s final scenes urges Kraken to rise up from the Sea and devour the film's hero – Jack Sparrow.

.jpg)

Someone who also evoked Kraken was the English author John Wyndham, who in 1953 wrote The Kraken Wakes. A novel that might appear as prophetic with its descriptions of advanced, technological warfare and global warming. The novel's main characters witness how five ”fireballs” fall from the sky into the sea. It takes years before people become aware that this was an invasion of aliens. The spacecrafts ended up in the deepest depths of the oceans. The creatures that emerged from them could only survive under the great pressure that exists in the most profound ocean depths. In principle, humans and aliens could thus coexist on earth. However, the human feel threatened by the alien presence. An English bathysphere is lowered to explore the giant Kraken-like creatures, but the aliens perceives the deep-sea submersible as a threat and attacks it and the death of the two Englishmen who manned is considered a declaration of war. Americans and Britons attack the aliens with nuclear weapons, with catastrophic consequences. The aliens are intelligent creatures and with the help of sophisticated weaponry ships are sunk all over the world and the global economy collapses. For unclear reasons, humans by ”naval tanks” snatched away from coastal areas, while the extraterrestrial technology melts the ice cap of the polar regions, to expand the habitat of the invading creatures, at the expense of humans. Huge crowds flee from low-lying areas and higher-lying countries are invaded y terrified migrants.

.jpg)

Finally, Japanese scientists manage to develop a weapon which through the use of ultrasound destroys the alien invaders, but by then one-eighth of the world's population has been wiped out, the climate has changed and the global sea levels are 40 meters higher than they were before the alien invasion.

.jpg)

For certain, Wyndham was inspired a H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, written in 1898. In this novel, the earth is hit by a number of meteorites, which turn out not to be of stone but being metal capsules containing octopus-like creatures from Mars. Their planet has become uninhabitable and the aliens had begun to look around in the solar system to find a new planet to settle. They are not at all willing to share the earth with any human midges and when a desperate defense is activated by the inhabitants of the world, it turns out that their military capacity does not at all affect the space creatures’ sophisticated weapon arsenal. Their main instruments of destruction are giant, tentacle-equipped tripods that with directed heat rays can shoot everything to smithereens, the killing machines is furthermore equipped with a deadly gas. With mechanical tentacles, the tripods capture humans, who they probably use them as food, or for fueling their machinery.

.jpg)

An artillery officer shares his opinions with the main character telling him that we humans have become like ants: like these insects we build our own cities, like ants we live our lives in them, but the ants have needs and habits completely separate from ours.

”There’s the ants builds their cities, live their lives, have wars, revolutions, until the men want them out of the way, and then they go out of the way. That's what we are now—just ants. Only—”

“Yes,” I said.

“We're eatable ants.”

In Spielberg's skillfully made version of The War of the Worlds from 2005, the main character and his little daughter are in an eerily intense scene threatened by a mechanical, sophisticated high-tech, efficient and flexible tentacle.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kytDzjuBGJI&ab_channel=Movieclips

The monster movies of the 1950s made octopuses return to popular comic books where they once had been quite common, though then as smaller creatures, now they more often appeared as huge, mutated monsters – like in the Marvel Comics. Somewhat later octopuses are even humanized, like like the diabolical Dr. Oc in Stan Lee’s The Amazing Spider-Man, who like the tripods in The War of the Worlds is equipped with deadly efficient, mechanical tentacles.

.jpg)

During the 1950s octopuses appeared in many so-called pulp fiction books:

and of course in a variety of comic books.

Earlier on, diabolical octopuses had also appeared in comics, which I devoured when they were reissued, such as Hal Foster’s well-drawn Prince Valiant, where the hero in an episode from 1938 is thrown into a well with a man-eating octopus, which he of course escapes from.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Octopuses were also frequent in Frank Frazetta’s Buck Rogers series from 1930s.

In the 1970s, Marvel Comics introduced a comic series about Conan the Barbarian based on Lovecraft´s friend Robert Ervin Howard's (1906-1936) 28 stories about the ancient superhero Conan. They had for the most part been published in the early 1930s in the U.S. science fiction-, horror- and fantasy magazine Weird Tales. Marvel Comics’ muscle-swelling Conan was a replica of Frank Frazetta’s muscle men, and in both books and comic magazines Conan, is involved in several fights with life-threatening octopuses.

A quite magnificent sequel to all these evil polyps is the humanized, deceitful and self-pitying manipulator Ursula, the sea witch in Disney's film The Little Mermaid from 1989. Ursula is endowed with an impressive body language and cynical words of wisdom, like:

Life's full of tough choices, isn't it?

"If you want to cross the bridge, my sweet, you've got to pay the toll.”

“They weren’t kidding when they called me, well, a witch.”

"Don’t underestimate the point of body language!”

.jpg)

During bygone days, octopuses were generally considered as insensitive, but strangely intelligent strangers, elusive to human intellect. Terrifying parasites capable of attacking and killing humans. So-called men’s magazines, or as they were called in the USA – Men’s Adventure Magazines offered descriptions of how testosterone-fueled men fought to the death with life-threatening, huge polyps, which with their nasty sucker equipped tentacles could squeeze the life out of their antagonists, or quite often – seductively shaped, scantily dressed ladies.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The tradition of the evil octopuses that had been revived by Victor Hugo in his Toilers of the Sea was constantly revised and evolving. The large mollusks could, as in Jean Delville’s 1894 painting Satan’s Treasures even be associated with the Devil himself.

.jpg)

A nasty octopus appears in William Hope Hodgson’s remarkable sea novel The Boats of the “Glen Carrig”, which was admired by Lovecraft and like his The Call of Cthulhu Hope Hodgson´s novel was apparently inspired by Edgar Allan Poe’s only novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket from 1838. In Hodgson’s novel from 1907, a huge octopus lurks under the Sargasso Sea, from where it attacks and devours the crews of every ship that happens to drift into these treacherous, algae-covered waters.

'.jpg)

.jpg)

In the 1880s, octopuses began to emerge as a symbol for ruthless capitalist forces that, for their own gain, sucked out life and well-being from innocent, unsuspecting and hard-working people. Each of the capitalist’s tentacles acted as an independent element, but they were all connected to the brain of a sinister capitalist, or an entire conglomerate of greedy parasites, sitting awaiting for their victims like spiders close to their huge, sticky webs. In 1882, the artist Frederick Keller published a satirical cartoon in which he likened the Southern Pacific Railroad monopoly to a giant octopus that controlled everything, while sucking the life blood out of California.

The author Frank Norris took Keller’s drawing as the starting point for his 1901 novel The Octopus: A Story of California. In the form of a thrilling Western the novel tells the story of a bloody conflict between ranchers and agents who work for the land-expropriating Southern Pacific Railroad.

.jpg)

The octopus eventually became a powerful symbol for all forms of syndicates and monopolies that devoured and extorted money from innocent people, such as Standard Oil in this satirical drawing from 1904.

.jpg)

The Italian mafia has often been likened to a vicious octopus, which tentacles enters and meanders everywhere, re-emerging as soon as they are chopped and whose head it is virtually impossible to access. For example, the mafia depicted in La Piovra, The Octopus, an excellent Italian TV series broadcasted between 1984 and 2001 as ten miniseries, exciting and with astonishing candor and accuracy it depicted the complicated interplay between State and mafia.

.jpg)

Since the second half of the nineteenth century, the octopus began to symbolize imperialism and could then be used as illustrating the greediness of England, Prussia or Russia.

.jpg)

Somewhat later, it was Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini who were portrayed as octopuses:

By the beginning of the last century, and onwards, the octopus metaphor was linked to conspiracy theories and nasty racism.

I have always been attracted by comic books, and as a boy I did with fascination in Hemmets Journal read in the comics about Prince Valiant and at the age of thirteen a classmate drew my attention to the comic book Flash Gordon, which like Prince Valiant was well-drawn and exotically interesting, with his evil Emperor Ming the Merciless who with iron hand ruled the planet Mongo and occasionally hissed: “Pathetic earthlings! Who can save you now?”

This was one of Max von Sydow’s recurrent utterances when he portrayed Emperor Ming in a unusually kitschy lousy film version made in 1980. When I now once again saw the film, I wondered if Stanley Kubrick had not been inspired by the scene where Flash Gordon is going to be executed and the eerily masked participants remind of the, of course, superior masquerade scene in Eyes Wide Shut.

In Flash Gordon, there were lots of episodes in which the superhero was attacked by various octopus-like monsters.

.jpg)

The demonic Ming with his oriental appearance and aptitude for exotic torture methods fits well into a genre of intelligent, but malicious, Chinese masterminds, often linked to criminal syndicates, all of whom striving after evil world domination. The master of this suspicious genre was the Englishman Rex Rohmer (Arthur Henry “Sarsfield” Ward) who created the super-villain Fu-Manchu, who also was the main character in a number of popular movies.

Fu-Manchu was n 1915 introduced i in the novel The Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu, in which his constant nemesis, Sir Denis Nayland Smith, stated:

Dr. Fu-Manchu rarely had been absent from my dreams day or night. The millions might sleep in peace – the millions in whose cause we laboured! - but we who knew the reality of the danger knew that a veritable octopus had fastened upon England – a yellow octopus whose head was that of Dr. Fu-Manchu, whose tentacles were dacoity, thuggee, modes of death, secret and swift, which in the darkness plucked men from life and left no clue behind.

Later he gives a lurid description of his arch-enemy:

Imagine a person, tall, lean and feline, high-shouldered, with a brow like Shakespeare and a face like Satan, a close-shaven skull, and long, magnetic eyes of the true cat-green. Invest him with all the cruel cunning of an entire Eastern race, accumulated in one giant intellect, with all the resources of science past and present... Imagine that awful being, and you have a mental picture of Dr. Fu-Manchu, the yellow peril incarnate in one man.

One of Fu-Manchu’s literary heirs is found in Ian Fleming’s misogynous and often openly racist novels about James Bond. Dr. No was written in 1958 as the sixth in a series of novels about the Secret Agent 007 “with license to kill”. The novel is clearly inspired by Fu-Manchu, with its wealthy oriental villain, a member of an international organization that, with the help of advanced technology, aims to destroy Western democracy through crime and corruption. In Dr. No and several other Fleming novels, the organization is called SPECTER, a crime syndicate directed by the world’s worst villains - surviving members of the Gestapo, the Soviet SMERSH, the Yugoslav OZNA, the Italian mafia, the Corsican Unione Corse, the Chinese Tong and the Triads, as well as the Japanese Yakusa and Black Dragon Society. SPECTER has an octopus as logo.

Dr. Julius No, with a German father and Chinese mother, was expelled from the Chinese Tong Syndicate after a theft and to punish him further the Organization had his hands cut off (thus Dr. No is like so many of Fleming’s villains – disabled). Dr. No succeeds, despite his lack of hands (he is equipped with technically advanced prostheses), in pursuing a sophisticated scientific career and at the same time create a fortune based on guano production on an island off the coast of Jamaica, which is largely his private property. After trying in vain to join the secret services of both the US and Soviet Union, Dr. No is finally recruited by SCEPTER, within which he reached a high position.

.jpeg)

James Bond is commissioned to examine Dr. No’s island facilities from which he is suspected of sabotaging the launching of long-range missiles from Cape Canaveral in Florida. However, Bond is captured by the sadistic Dr. No, who has a great interest in the human body’s ability to endure pain. Bond is thus forced to, under observation, travel through an obstacle track constructed in Dr. Nos underground ventilation system. After enduring painful trials, including almost lethal electric shocks and encounters with large poisonous spiders, Bond finally ends up in a pool separated from the sea by a high metal fence. There he is surprised by a giant squid. To escape the beast, Bond is forced to climb up the fence, from where he looks down into the water below him where “a forest of tentacles” swings back and forth like thick snakes. The animal is as big as a steam engine:

The eyes watched him, coldly, patiently. Delicately, like the questing trunk of an elephant, one of the long seizing tentacles broke the surface and palpated its way up the wire towards his leg. It reached his foot. Bond felt the hard kiss of the suckers. … Like a huge slimy caterpillar, the tentacle walked slowly on up the leg. It got to the bloody blistered kneecap and stopped there, interested. Bond's teeth gritted with the pain. He could imagine the message going back down the thick tentacle to the brain: Yes, it's good to eat! And the brain signaling back: then get it! Bring it to me! Bond took a quick glance into the two football eyes, so patient, so incurious.

.jpg)

Bond has wedged his arms between the metal wires of the fence and hang from his armpits while the octopus winds his tentacles along Bond's body, trying to drag him into the water. At first Bond does not manage to free his arms from the fence and it feels as if he is going to be torn pieces. However, with one hand he succeeds to break off a piece of steel wire and eventually release his arms from the fence. He allows the monster’s tentacles to drag him towards its head and the menacing beak at the center of the vigorous feelers. On the brink of being torn to pieces by the hardy beak, Bond manages to wedge his legs into the fence and suspended by his knees he ends up hanging upside down while facing the sinister octopus. With one hand Bond plunges the steel wire straight into one of the monster’s eyes. Suddenly, everything around Bond turns black. The octopus has released its sticky, ink-like protective substance, with a scent of ammonia and rotten fish. When Bond regains his senses, he finds himself surrounded by pitch black water, though the octopus has disappeared, hopefully it has died and sunk to the bottom of the pond. James Bond manages to find a way out, gets hold of Dr. No and succeeds, by changing the direction of a loader in the harbor, burying him alive under a stream of stinking guano.

Dr. No’s affinity with its octopus is obvious. Both creatures, like all of Ian Fleming's villains, are strangers; abnormalities, exceptions proving the perfection of Creation. In a contribution to a collection volume about the Bond phenomenon, Umberto Eco (1932-2016) put his finger on this distinctive feature of Ian Fleming's books:

The Villain is born in an ethnic area that stretches from central Europe to the Slav countries and to the Mediterranean basin: as a rule he is of mixed blood and his origins are complex and obscure; he is asexual or homosexual, or at any rate is not sexually normal: he has exceptional inventive and organisational qualities which help him acquire immense wealth and by means of which he usually works to help Russia: to this end he conceives a plan of fantastic character and dimensions, worked out to the smallest detail, intended to create serious difficulties either for England or the Free World in general. In the figure of the Villain, in fact, there are gathered the negative values which we have distinguished in some pairs of opposites, the Soviet Union and countries which are not Anglo-Saxon (the racial convention blames particularly the Jews, the Germans, the Slavs and the Italians, always depicted as half- breeds), Cupidity elevated to the dignity of paranoia, Planning as technological methodology, satrapic luxury, physical and psychical Excess, physical and moral Perversion, radical Disloyalty.

Dr. No is not the only Bond villain with an affinity for octopuses. In Ian Fleming’s last Bond story, Octopussy, which was published posthumously, villain and octopus are united in an almost erotic, deadly embrace.

Major Dexter Smythe an elegant, retired marine biologist and former spy, has withdrawn to Jamaica. During the war, Smythe murdered Bond's friend Hannes Oberhauser, after they together had found a treasure trove of hidden Nazi gold. Since then, Smythe had sold the gold bars, one by one, to the Chinese Foo brothers, who smuggled them on to Macao. After Bond reveals him, Smythe takes his daily swim to feed his beloved pet – an octopus he has named Pussy. However, Smythe is stung by a scorpion-fish and lethally poisoned he seeks out his beloved Pussy:

Yes! The brown mass was till there. It was stirring excitedly. He heard himself babbling deliriously into his mask Pull yourself together, old boy! You’ve got to give Pussy her lunch! […] And then the tentacles leaped! But not at the fish! At Major Smythe's hand and arm. Major Smythe's torn mouth stretched in a grimace of pleasure. Now he and Pussy had shaken hands! How exciting! How truly wonderful! But then the octopus, quietly, relentlessly pulled downward, and terrible realization came to Major Smythe. […] The tentacles snaked upward and pulled more relentlessly. Too late, Major Smythe scrabbled away his mask. One bottled scream burst out across the empty bay, then his head went under and down, and there was an explosion of bubbles to the surface. Then Major Smythe's legs came up and the small waves washed his body to and fro while the octopus explored his right hand with its buccal orifice and took a first tentative bite at a finger with its beaklike jaws.

The Bond film Octopussy from 1983 is completely different from the short story. Admittedly, Dexter Smythe also appears in it, but it is his attractive daughter Octavia, in the film played by Swedish Maud Wikström from Luleå, who keeps an octopus as a pet. In her case it is a small blue-ringed variant, which bite is fatal. All octopuses are poisonous, but only the blue ringed one can kill. Octavia, who is called Octopussy by her father, does not appear in Fleming’s short story, though hers and the octopus’ deadly connection is, as so often by Fleming, spelled out.

.jpg)

The erotic attraction of octopuses is yet another of the strange aspects that the animals seem to fascinate people with. In Japanese folklore, octopuses often have terrifying properties. Then in the form of Akkorokamui which apparition, like that of the Kraken, can be rather indeterminate and it is this included in the group of Ayakashi, a collective name of all yōkai – monstrous sea creatures creatures with an appetite for human flesh.

.jpg)

.png)

However, yōkai also has another aspect well known through their manifestation in one of Hokusai’s woodcuts – The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife from 1814. The image is an example of the so-called tentacle eroticism, shokushu goukan, a pornographic genre depicting women’s intercourse with octopuses and fictional monsters.

.jpg)

However, it is as a blood-sucking monster that the octopus retains its lugubrious character during most of the last century. Especially Nazi propaganda linked its xenophobia with octopuses. The so called “World Jewry” was portrayed as a monstrous octopus in the process of sucking strength and wealth from the world's population, an image that could easily be exchanged for another monster, not equipped with eight arms, but eight legs instead, though just as disgusting – the poisonous spider.

.jpg)

Dictators such as Hitler and Stalin could then be portrayed as fighting octopuses in the form of Judaism or communism, which in the drawing below by Arthur Johnson is described as "Marxism".

.jpg)

Arthur Johnsson (1874-1954) was the son of the German consul in Hamburg and as an early and fanatical Nazi he became a popular cartoonist who in several illustrations in German “satirical media” in various ways praised Adolf Hitler as a defender of German values, or as here as the destroyer/transformer of degenerate German art.

.jpg)

The nasty connection between Judaism, conspiracy theories and octopuses has continued into our time, for example when supporters of Victor Orbán in Hungary portray philanthropist George Soros about a manipulative, world-controlling octopus

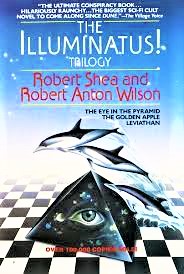

Wilson’s and Shea’s The Illuminatus Triology from 1975 is an outlandish parody of all sorts of nutty conspiracy theories. An absurd, but occasionally quite amusing concoction where the action takes place in alternative universes where quantum physics mixes with New Age, conspiracy theories, pseudo-history, mythology, religion, fantasy, sciencie fiction, B movies, comic books and rock music. It appears as if the authors were under the influence of drugs while writing most of the confusing text and it is no wonder that the LSD guru Timothy Leary, “turn on, tune in, drop out”, praised the novel trilogy as a masterpiece.

A bunch of police detectives and journalists who call themselves The Discordians are opposing the sinister Illuminati , well-organized criminals who obviously are trying to make the entire world order collapse. Somehow an octopus-like monster, Leviathan, which pyramid-shaped and amoeba-like is resting on the ocean floor, seems to have something to do with it all. But, when the heroes onboard the millionaire Hagbard’s golden submarine finally confront the monster and through the submarine’s computer system manage to synchronize its thoughts with other beings, Leviathan’s evil aversion to humanity comes to an end when it understands that it was all the result of a boundless sense of loneliness. The Illuminati can finally be defeated and disappear into the unfathomable eternity of the Universe.

.jpg)

Of course is the golden submarine related to The Beatles’ yellow submarine and thus also to Ringo Starr’s charming Octopus's Garden. He wrote it when he left The Beatles after a crisis in the late summer of 1968. Ringo vacationed in Sardegna where he from fishermen learned that octopuses create small gardens on the seabed. Perhaps his song expressed a desire for liberation from all the madness that had been built up around The Beatles. However, Ringo eventually returned to the famed rock group and his garden song was included in their album Abbey Road.

It is possible that Ringo’s song was part of a trend that was changing octopuses from being cruel monsters into appreciated and sensitive creatures. Nevertheless, you still eat them with good appetite. I must admit that I with great appreciation feast on fried squid and octopuses together with a well-chilled, tasty and healthy, white wine, though a light, cool red one also goes well with frutti di mare, especially if I can enjoy it all with a sea view.

Sympathetic octopuses began to appear in children's programs, such as Squiddly who made his debut already in 1965. With a sailor’s cap and always in a good mood, Squiddly worked in Chief Winsley’s aquatic park Bubbleland, which he constantly tried to escape from while intending to intitiate a musical career on his own. Squiddly could with his many tentacles play a wide variety of instruments However, the cheerful octopus became saddened when people were frightened by him, assuming he was a dangerous creature.

.jpg)

Perhaps after having a bad conscience for presenting the magnificent but vicious sea witch Ursula as a malicious octopus in The Little Mermaid, the Disney Company did in its sequels introduce the sympathetic little Ollie Octopus, good friend of the mute mermaid Gabriella.

.jpg)

In the Disney film Searching for Dory, a somewhat grumpy, though nevertheless warm-hearted octopus appears. In fact Hank has like other octopuses no less than three hearts. Like them, Hank is also a master of disguise and can, by changing his appearance in relation to the environment, become almost invisible. When Hank gets upset, he also secretes an ink-like substance. By the end of the movie, Hank becomes a hero while helping his aquatic friends escape from captivity and survive in the vast ocean.

.jpg)

With properties such as changing the colour and texture of his skin, the strange suckers, his agility and adaptability, his ability of compressing his body in such a way that he can pass through tight spaces, his three hearts and intelligence, it may seem as if Hank belongs in the realm of fantasy. However, the reality is even more astonishing—octopuses can cause make wounded or even disappeared tentacles to grow back again. They can open the lids of closed glass cans, both from the outside and the inside, by gaining experience they are also able learn to open childproof cans. Their sight and memory are excellent. They live solitary lives and without parents, but nevertheless appear to have different and well-developed personalities. They learn new skills and can even move across land. Their central brain is coordinated with the nervous system of the tentacles, which obviously are endowed with a faculty of acting partially on their own.

.jpg)

Octopuses use 168 different protocadherins, humans have 58. Cadherins are a type of cell adhesion molecules and are crucial for the formation of so called adhesion-crossings causing cells to attach to each other, a function that regulates tissue growth. Cadherins allow cells to repair damage. When, for example, a wound occurs, cahderin makes skin cells feel that there are no cells next to them and begins to repair the dent. An ability that in octopuses is highly developed. Perhaps most remarkable of all is that all these abilities and qualities are allowed to work and develop for such a short time. An octopus lives on average only three years. Males die after mating and females after their eggs have hatched.

Despite their short lifespan, octopuses have had a long time to develop. Their evolution has been incredibly much more time-consuming than that of Homo Sapiens and this impressive evolution span seems to have taken place in parallel with humans. The strange creatures were almost fully developed even before human beings appeared. Below is an octopus fossil from the Jurassic era. The fossil is more than 183 million years old and was created long, long before man appeared on earth.

In his 2016 study Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness, Peter Godfrey-Smith, Professor of History and Philosophy at the University of Sydney, takes as his starting point the fact that intelligence has developed separately in two groups of animals – in cephalopods, ieoctopuses and ten-armed squid, as well as sepia squid, and in vertebrates, such as birds and humans. Godfrey-Smith notes that an octopus is probably the closest we can get when it comes to meeting and studying an “intelligent alien”. According to Godfrey-Smith, an octopus’s mind is the one most “different” from the human mind.

.jpg)

A popular feature of this benevolent change in the view of octopuses is the documentary My Octopus Teacher. It tells the story of how a documentary filmmaker named Craig Foster retreats to False Bay, not far from Cape Town, where he spends his days dives into the dense kelp forests. In there he meets a females octopus, which for a year lets him follow her daily life; playing with him, hunting, eating and sleeping. She is constantly fighting pajama sharks which at one point tear off one of her tentacles. The octopus isolates herself until her tentacle has grown back after three months. By then, she had learned to escape the pajama sharks, among other things by swimming up over their backs and thus coming out of reach for them. After she mates and her eggs have hatched, the octopus swims away and dies.

.jpg)