ART'S INNER SPACE

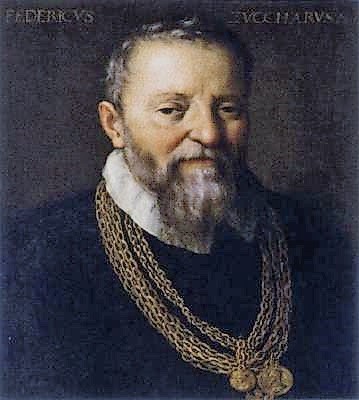

When my friend Örjan asked me if I knew of any artists who had written about art and then specifically dealt with their own artistry, I couldn't find any names that he didn't already know. However, when I a few weeks ago rummaged through the books in an antiquarian bookshop I found a book with texts by Federico Zuccari (1539 –1609).

.jpeg)

Zuccari and his older brother Taddeo were in their time well-known artists. In Rome, their paintings can be found in many palaces and churches. In my opinion, Federico is the more versatile of the two, while Taddeo comes off as rather awkward.

.jpg)

Federico shifts between different styles, often elegant, although rather inconspicuous, at least compared to great masters like Titian and Raphael. Despite this, by Titian’s death in 1576 Federico Zuccari was by several art connoisseurs regarded as Italy's foremost artist.

.jpg)

Federico worked for Italy’s leading princely houses, for the Pope in Rome, Philip II in Spain and Queen Elisabeth I in England. Wealthy and influential, he built a palace in Rome next to the Church of SantissimaTrinità dei Monti located by the crest of the Spanish Steps. Due to its bizarre frescoes, windows and portals, Zuccari's residence was called Casa dei Mostri, the House of the Monsters.

.jpg)

Federico Zuccari was a controversial and easily hurt man, who constantly managed to make himself uncomfortable. However, impetuousness, diligence and zeal for work made him sought after by a variety of employers. Furthermore, he was a tireless self-promoter and diligent writer. A drawing by Federico shows him and his brother working on a fresco at a Roman wall, while an admiring Michelangelo holds his horse to have an appreciative look at their work.

Michelangelo was Federico’s great role model and he was eventually by Pope Gregorio given the honorary commission to complete Michelangelo’s work in the Pauline Chapel, where cardinals gathered to elect a new pope and where, twenty years earlier Michelangelo had in 1549 completed his last paintings - The Conversion of Saul and St . Peter's Crucifixion.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Another task Federico carried out in the shadow of a great genius was the frescoes under the famous dome which Brunel1eschi in 1436 had struck over the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. After its completion its interior had been left whitewashed in anticipation of its 3,600 square meters becomimng adorned with a fresco. It was first in 1571 that this assignment was awarded to Giorgio Vasari, though he died after two years. Vasari had by then covered a third of the surface with his paintings. A year later, Francesco Medici decided that the thirty-five-year-old Federico Zuccari would complete the work, something which he achieved in less than five years.

The result was not at all appreciated by the Florentines. They were shocked by the glaring obscenities of the infernal scenes where rammish sinners by grotesque devils were sodomized with burning torches.

.jpg)

It was also considered something of a gross sacrilege when Zuccari, with a startling headdress and a palette in one hand prominently , portrayed himself and members of his family among the celestial hosts.

Lampoons were written and many argued that the demonic scenes should be painted over. Zuccari feigned unconcern and through his arrogance and wicked sense of humour he attracted even more scorn upon himself A contributing reason for the Florentines’ dislike of Federico Zuccaro may also have been that het often expressed his disdain for what he called the “Florentine manner”. He came from the small, provincial town of Sant'Angelo in Vado in Marche. The Florentines in particular, but also the Romans, were also annoyed by Zuccari's sleight of hand and the scattered presence of his diverse works. It became a saying that when someone dismissed a mediocre work, which master they did not know, they did so with the words: “Surely made by a Zuccari”

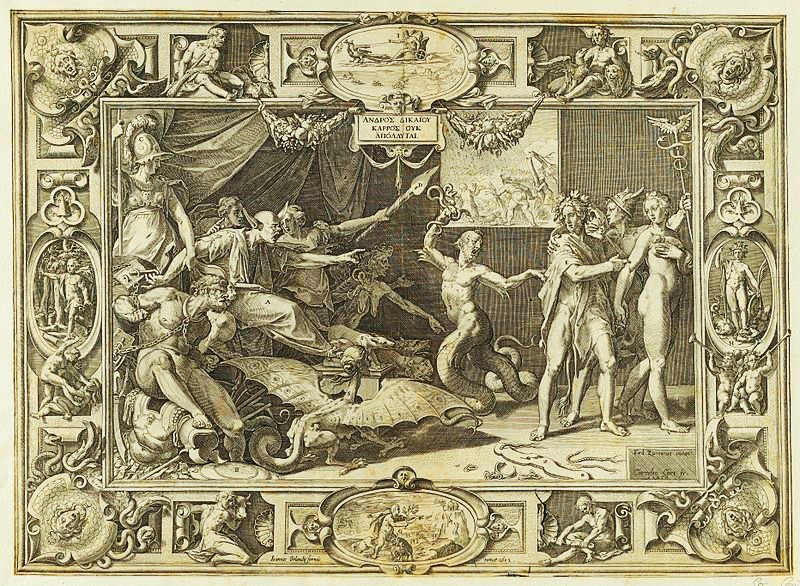

Federico liked to excel with his literary culture and knowledgeable references to classical writers. When Cardinal Alessandro Farnese in 1569 fired him from the construction site of his palace in Caprarola, Zuccari spread a number of engravings alluding to the ancient story about The Calumny of Apelles (which earlier had been famously depicted by Botticelli). The depiction of this incident alludes to an artist being judged by an ignorant prince with donkey ears, an allusion to Midas who preferred the art of Marsyas to that of Apollo. In Zuccari’s etching Midas has the appearance of and Alessandro, who acts on the advice of personifications representing Calumny , Ignorance, Suspicion, Fraud and Conspiracy. The motif was originally described by Luciano of Samosata (120-180 AD) and was one of Federico's great favourites and he made several versions of it.

During his time in Rome, following the completion of the Florentine frescoes, Federico was commissioned by Paolo Ghiselli, papal scalco, i.e. a high-level chef in charge of the papal kitchen. Ghiselli was eager to announce his elevated social position by paying for a fresco intended to adorn a chapel in Santa Maria del Baraccano, situated in his and the Pope’s hometown, Bologna. The subject was San Gregorio's Procession to Prevent the Plague in Rome. The Pope, Ugo Boncompagni, had chosen Gregorio as his papal name.

Zuccari devoted great effort to the realization of this prestigious work of art, evident from the many drawings that have been preserved. However, his proposal was not liked, probably because it was fiercely criticized by Bolognese painters who wanted to protect their city’s art market from “alien” encroachment.

Zuccari was not paid for his work. An unsigned note declared that his proposal was “fuzzy” and “undignified”. The artist became enraged and on the annual feast of Saint Luke, patron saint of Rome’s artists, he unveiled a large canvas in Chiesa dei Santi Luca e Martina in Rome’s Forum. Zuccari called his work Porta Virtutis, Gate of Virtue.

To his fellow artists and a general public, Zuccari explained the painting's allegorical allusions. However, the intention was obvious to everyone, not least because the ambitious chef, Paolo Ghiselli, was shown in the foreground of the painting, naked and accurately portrayed, wearing the unflattering donkey ears of King Midas and surrounded by malicious, cunning animals, such as aq wild boar and a fox, as well as ominous and repulsive figures, such as Envy, represented as a terrifying and ugly witch, who with sagging breast and entwined by poisonous snakes is lying on the ground while she clings to Ghiselli's leg, in the company of other deformed characters, such as Malice and Defamation. In the centre, Zuccari's work is defended by an imposing Minerva, who advances towards the viewer while blocking the entrance to the Garden of Virtue.

.jpg)

Ghiselli, deeply offended by the insult, succeeded in having the painting confiscated. Scandalized, the chef then turned to his employer Gregory XIII and Zuccari was sentenced to lifelong banishment from Rome. He moved first to Florence and then to Venice. However, at the insistence of prominent Roman artists, Zuccari was pardoned five years later and was then able to return to Rome in triumph.

In 1591, The Roman Senate gave him the hereditary title of Roman Patrician, proclaiming that it would be inherited by his descendants. In 1595 Zuccari was appointed leader for life of the Academy he had founded in Rome and shortly before his death in 1609 Zuccari was ennobled.

Vulnerable and ambitious, Zuccari was a master of self-promotion. By publicly exhibiting his works and ensuring that any criticism directed at him could be inflated and remade as artistic spectacles, he ensured that his name was on the lips of art connoisseurs and patrons. He knew that through an intellectual appearance as an art historian and classicist he could contribute to raising the social position and general status of artists. It was to that end that he founded Rome’s Academy of Art, so young artists could not only be taught advanced artistic skills but also be endowed with an excellent literary and philosophical education. In time, Zuccari became famous not only for his artistic skills but also as an influential writer and sophisticated philosopher of art, in the wake of Aristotle and Plato.

His books were constantly reprinted – Lettere ai Principi e Signori Dilettanti di Disegno, Pittura, Scultura e Architettura, scritte dal cavalier Federico Zuccaro, all'Accademia Insensata con un lamento per la Pittura, opera di lui stesso and Idea de Pittori, Scultori e Architetti, i.e "Letter to Princes and Art Lovers Concerning Drawing, Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, Written by Cavalier Federico Zuccaro, to an Insensitive Academy, with a Complaint on the State of Painting, a Work of His Own" and "An Idea of Painters, Sculptors and Architects."

It was extracts from these books I found in the antiquarian bookshop. As a point of departure Zuccari applied theories that flourished through Neo-platonic findings among contemporary humanists and introduced what he called his concetto formula. According to Zuccari, il concetto was an inner “drawing” created in the mind of an artist. A “mirror image”, which in both dreams and consciousness reflects the objects that our vision carries into our interior, where they are embellished and “deepened” by our imagination. .

God does not reflect anything - he creates. Nature is and remains exactly as God created it. It is real, tangible, but what man creates are “artificial” mirror images, rendered with more or less great “artistic skills”. Art is thus “a copy of nature”, though not das Ding an sich, the thing in itself. All art is an interpretation.

There are several manners in which nature might be interpreted/depicted. One is the exact representation, what Zuccari calls “a reproduction of an external image”, i.e. God's creation/nature. As an imitation of an already existing reality, such an “interpretation” becomes nothing more than an “imitation”, the art of a monkey, which only presents what God has already created. Man is not God and therefore his art should be no more than “human” art, it cannot pretend to be at the same level as God’s creativity..

.jpg)

Zuccari distinguishes three stages of human concetti – an image of reality that a skilled artist has been able to create within himself and present to his audience. An art that radiates a detailed, perfectly produced/designed mirror image of the reality it he depicts - people, landscapes, animals and nature. This skill is nonetheless inferior to what Zuccari terms as an “artistic image” through which the soul has transformed a painters impressions into "a rare, artistic image" that reshapes and deepens our view of God’s Nature.

However, the greatest, most truly human art is La bella pittura – something that is more than just “a craft”. It is through La bella pittura that an artist’s true greatness becomes evident, when he, like Michelangelo, is able to creates an art that is far more than an ”imitator, or flatterer of nature", when art becomes something completely new, something never seen before. Enriched, transformed by astonishing inventions, fantasies and ghiribizzi, rarities.

.jpg)

Of course, Zuccari counted himself as one of those divinely blessed artists, something he proved through his Florentine frescoes and numerous illustrations for Dante’'s Commedia.

.jpeg)

.jpg)

A true artist is able to look into the depths of his own soul, the place where God’s true spirit reside. His Creative Power. Inside his own mind, a sincerely searching artist is dazzled by the divine spark we all carry within us. The source of life. If such an artist manages to capture even a fraction of the creative ligh,t and reflect it in his art, he thereby becomes more praiseworthy than his less talented colleagues. Such an artist creates tastico, the highest stage of art—the external, innovative, eloquent, rare image that perfects all that an unbridled imagination can envisage. In such Bella Pittura, the three concetti of the soul are united – craftsmanship, originality and the God-given creative spark. This, according to Zuccari, is the at the core of true humanism, the one which makes us humans unique – the fact that we are created in the image of God.

A forma spirituale which, through colour and line, unites the universal with the personal/the particular and thus expresses the divine spark with human nature. Angels cannot accomplish this, they are part of God’s Nature. They lack sensitivity, a nature of their own and thus also concetti.

By being able to create artistic images within oneself, man differs from God. God is perfect. In His existence, through His substance, He includes everything. All that is in God – is God. Man, on the other hand, carries within himself a multitude of unrealised possibilities; images, comparisons, creative elements. A kind of confusing chaos that constantly strives towards perfection, but never achieves it. A curse, but also a joy. The happiness of being. A contentment that actually is the greatest delight within human creation. God’s gift to us humans.

In art, natural forms are transformed into matter, revealing human indeterminacy and the confusion that different sensory experiences give rise to. We can never achieve, never experience the clear order of nature/God, but we might discern something of the idea behind it all, how the immensity of God’s might be conveyed through an art able to make our lives, our waiting for perfection, bearable.

Enough of theory – now let me leave all that behind and get down to the essentials … the viewing of art. That I became by Zuccari’s speculations was probably because he hinted at something that had always captivated when it comes to art - its distinctiveness, the sense of alienation it provides. How its special position alongside everyday life opens gates to a parallel reality. A subtle presence where terror and safety exist side by side in a flamboyant, strangely joyful world that both is present and non-existent, talking to something that lives in my interior, to my concetto.

For as long as I can remember, there has existed images within me, things I have seen in books and on walls. They have grown within me and become part of my dreams and fantasies. Often they are both terrifying and exciting. There are, of course, Disney's queens of hell.

.jpg)

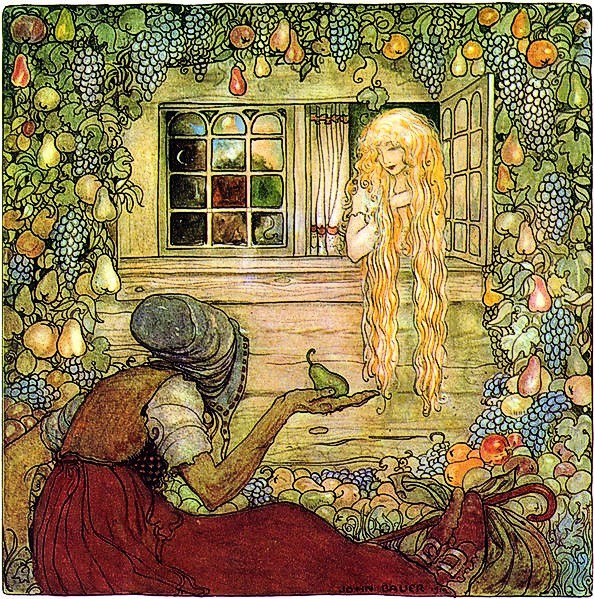

However, the image that most clearly reflects my childish entry into the world of art was a reproduction of John Bauer’s Out into the Wide World, which hung in my mother's girl's room in her childhood home. The little boy who, on his impressive runner, looks out over the enchanted world of fairy tales carried with him everything I loved about art.

.jpg)

My grandparents were fond of the Finnish-Swedish Zachris Topelius's (1818-1898 poems and stories and it was in their large house in Stockhom’s lush suburb Enskede that I became familiar with Topelius’s saga Sampo Lappelill, a delightfully eerie story about how a small Sami boy during the longest night of the midwinter witnesses how the mighty Mountain King Rastekai gathers all the animals of the North to announce his intention to extinguish the sun. Rastekai wants to kill Sampo Lappelill, supported by his fierce trolls and predators he tries to annihilate the troublesome witness and a wild chase over snow-glittering mountains begins. However, on the back of the golden-horned reindeer Hiisi, Sampo manages to escape the terrifying Rastekais. Time and again I returned to the fascinating illustrations of this thrilling story.

.jpg)

They reminded me of the eerie ghost hunt in Goethe’s Erlkönig that Grandfather told me about and showed pictures illustrating the gruesome poem:

My father, my father, he seizes me fast,

For sorely, the Erl-King has hurt me at last.

The father now gallops, with terror half wild,

He grasps in his arms the poor shuddering child;

He reaches his courtyard with toil and with dread,

The child in his arms finds he motionless, dead.

He also told me about Faust and the mysterious tale of Undine, the Water Spirit.

Shakespeare's stories

and Arabian Nights:

If the Arabian Nights shimmered with all the lures of the Orient, Finland became through Topelius, but mainly through the Moomin trolls and the Kalevala, home to all kinds of exciting natural mysteries.

The fairy-tale forests extended east into Alexander Afanasye’'s fairy tales, evocatively illustrated by Ivan Bilibin (1876-1942)

and south to the black, German forests of the Brothers Grimm, in the depths of which the man-eating witch from Hansel and Gretel had her abode.

Doré and Perrrault brought me to the forests and medieval castles of France

.png)

and its Parisian salons, peopled by Grandville’'s insect people.

.jpg)

In Enskede, there were also the drawings in Åhlén and Åkerlund’s story collections Bland tomtar och troll, Among Gnomes and Trolls. They came out at Christmas time and I read them with great fascination. First of all, the earlier editions with illustrations by John Bauer (1882-1918), which I found in Grandfather’s bookshelves.

But I was also charmed by Einar Norelius’s (1900-1985) pictures in later editions. In particular, I was drawn to a strange image of his depicting mysterious forest demons performing a nocturnal ring dance around a lugubrious tower in the depth of the Nordic forests.

I also read the later stories and was then captivated by Hans Arnold's (1925-2010) illustrations,

which then appeared in several of the horror stories that I have read since then,

often attracted by more or less suggestive illustrations.

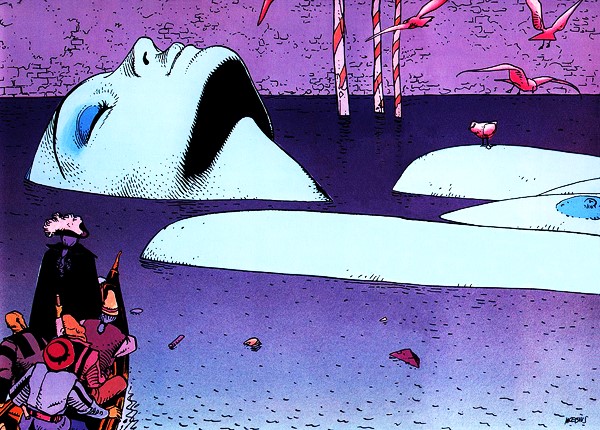

Science fiction:

.jpg)

Fantasy:

and of course exotic horror stories, as in the collection of stories below, otherwise unknown to me, in which I was particularly fascinated by a story about how a captain on a slave ship was bitten in the throat by a female slave. The wound became infected, rotted, grew and eventually turned into teeth, lips and tongue, which through demonic whispering drove the captain into insanity.

That my great interest in fairy tales, eventually attracted me to depictions of horror was probably a completely natural development. Fairy tales are generally filled with subtle horror and I didn't mind that at all. I was fascinated by dreadfulness.

Thrilled and chocked when Knight Bluebeard’'s wife finds the room with her murdered predecessors. I couldn’t explain why when my school teacher angrily wondered why I had made a drawing of hanged women whose blood dripped onto the basement floor..

It was not until Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales aooeared in 1975 that I found a rasonable explanation to my fascination with horror. Bettelheim explained that it was wrong to gloss over and correct the horror ingredients of folktales. They actually help children to confront difficult existential problems, such as separation anxiety, Oedipal conflicts and sibling rivalry. The extreme violence and nasty feelings in many fairy tales serve to deflect anxieties that often harass children, breeding their fantasy and imaginations,

Bettelheim turned out to be a fabulist as well. Someone who created a fairy tale of his own life - it turned out that it was not true that he acted as an "educator and therapist for severely disturbed children", neither had he been a friend and disciple of Freud. In fact, Bettelheim was not even a psychologist. He had only taken three introductory courses in psychology. As he wrote himself:

We must live by fictions – not just to find meaning in lifer but to make it bearable.

Nevertheless, I found Bettelheim’s book to be interesting, even if he had plagiarized much if it from a certain Julius Heuscher.

After Bettelheim it was not entirely wrong to appreciate horror stories and, like several of my generational comrades, I was both attracted and frightened by Disney's masterpiece. The nasty queens in Snow White and Sleeping Beauty were present in my dreams.

and so were evocative images from, for example, Disney’s Pinocchio. When I in the middle of the night woke up alone in a deserted house, memories remained from when Pinocchio woke up in Mangiafuoco's circus wagon and found the marionettes swaying back and forth like Bluebeard’s hanged and bloodied ladies.

Incidentally, I have read Carlo Collodi’s Le aventure di Pinocchio. Storia di un burattino, several times. A picaresque novel that never ceases to fascinate, not least through its eerie atmosphere. Like when the confused abd lonely Pinocchio in a dark forest finds himself in front of the Blue Fairy’s house:

At the noise, a window opened and a lovely maiden looked out. She had azure hair and a face white as wax. Her eyes were closed and her hands crossed on her breast. With a voice so weak that it hardly could be heard, she whispered:

"No one lives in this house. Everyone is dead."

"Won't you, at least, open the door for me?" cried Pinocchio in a beseeching voice.

"I also am dead."

"Dead? What are you doing at the window, then?"

"I am waiting for the coffin to take me away."

Someone who captured the disturbing moods of Pinocchio; the poverty, the cold and oddities, is the Italian illustrator Roberto Innocenti (1940-)

Pinoccichio has over the years attracted a large number of artistsm, among several film directors (there are at least thirty Pinocchio films). In addition to Innocenti, I should perhaps mention another Italian master illustrator - Lorenzo Mattotti, who, in addition to Pinocchio, has illustrated a number of classics.

His interpretation of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is characterized by a kind of maddening dynamic.

This is far from the creepy, menacing darkness of Corrado Roi’s (1958-) depictions of the Apocalypse and the terrors of modern Italian horror magazines.

.jpeg)

Italian art history presents many examples of what Zuccari named La Bella Pittura, in the sense of a sublime horror sprung from an artist´s concetti. Zucarelli's contemporary, the Sienese Domenico Beccafumi (1486-1551), did for example frighten me when, in his painting The Fall of the Rebellious Angels, which I was confronted with in Siena’s Pinacotheca. In it I discovered the cellars of Hell and in one of the corridors a demonic flame appeared to move rapidly towards the viewer. I don't really know why I felt a cold chill down my spine, but assume I had seen something similar in a nightmare.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Another nightmarish sensation seized me when I in Girolamo Savoldo's (1480-1548) The Temptation of St. Anthony discovered a naked, corpulent man carrying a terrifying monster on his back.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The eccentric Neapolitan Salvator Rosa (1615-1673) tried to survive as an independent artist, freed from the demands of patrons, the Church and other controlling purchasers, ti that end he occasionally exhibited his works of art along the streets of Rome and Naples, at the same time as he made himself known as author of several socially critical writings. Perhaps to appeal to a sensationalist public, Rosa excelled in horror depictions with witches and monsters appearing within in a dark and threatening universe.

.jpg)

Rosa's gloomy landscapes might be considered as a world seen through a temperament and may the landscapes of the Dutch Jacob van Ruisdal (1629-1682).

.jpg)

Rosa’s and van Rusidaì's pictorial worlds are images of God's nature, depicted as in the fresh air, quite different from Piranesi’s (1720-1758) dungeons. They are, far from cramped and suffocating, rather intricate and endless, like labyrinths encountered in dreams, without openings and exits they seemed to include the edntire world, places of torture and despair.

Like Rosa’s paintings, Piranesi’s carceri were part of an evil world without mercy and to that extent they were also images of their own cruel times with their wars, famine and governmental abuse, like Alessandro Magnasco’s (1667-1749) sepia brown worlds of cemeteries, monasteries , torture chambers and slaughter.

.jpg)

The worlds of Grimmelhausen (1621-1676) and Jaques Callot, (1592-1635) were also grotesque dream worlds mixed with icy depictions from a merciless era of religious wars and unjustified violence.

.jpg)

A world that was also Goya’s world, filled as it was with witches and demons.

A mute but still roaring, oppressive nightmarish world where Reason sleeps, leaving the field open to demon the mind mixing with an all-too-tangible reality, without grace, salvation, or pity.

.jpeg)

A hell far worse than what a visionary Dante could dream up and express, but cruelly present to a front-line soldier or holocaust victim.

.jpg)

.jpg)

A place where the entire world is a prison, a torturing chamber, that, like Piarnesi’s dungeons, but a nauseating reality, which, unlike them is cramped and deadly.

.jpg)

A world harsh, merciless and demonized like those of Magnasco, Callot and Goya are depicted by artists such as the Polish Zdzislaw Beksinski (1929-2005),

or the Slovenian Marko Jakše (1959-)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Such works of art seem to arise from Zuccari's cocetti and constitute a part of what he calls La Bella Pittura, There we find in Ferrara San Giorgio fighting the dragon in Cosme Tura's (1403-1485) marvelously sharp, unforced,

winding movement.

.jpg)

The Danish Christoffer Eckersberg's (1783 -1853) moonlit night in Copenhagen where a man runs along Långebro to rescue someone we cannot see.

Rerthel's Death inspects its victims at a barricade from 1848.

.jpg)

A gloomy, misanthropic and misunderstood Alberto Martini (1876-1954) digs in Milan among his peers from literary history and depicts their anguish through the lens of his own agony.

.jpg)

.jpg)

All the while Leon Splilliart (1881-1946) sleeplessly wanders along Ostend's empty streets, quays, piers and beaches.

.jpg)

At night it is desolate and empty in Belgium's cities and parks, where we find Degouve Nunqes (1867-1935)

.jpg)

Xavier Mellery (1845-1921)

Ferdinand Knopff (1858-1921)

.jpg)

Carel Willink (1900-1983)

.jpg)

Paul Delvaux (1897-1994)

and René Magritte (1898-1967):

When the day dawns, Johannes Moesmans (1909-1988) The Rumour cycles in naked with a violin on the luggage rack

.jpg)

And the struggle for existence can begin again, as when James Ensor's (1860-1949) skeletons fight over a smoked herring.

.jpg)

Anxiety and loneliness also thrive in the East, for example with Alfred Kubin (1877-1959)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

and František Kupka (1871 -1957) in Prague.

Artists who seem to walk along the Germans’ trodden paths

One of Swiss Johann Henri Füssli's (1741-1825) four versions of his expressive Nightmare now hangs in Goethe’s house in Frankfurt, though it never belonged to the great author. Had he had it one been in his bedroom, perhaps it would have given rise to nightmares like those that Max Klinger (1857-1920) so skilfully depicted in his absurd series of etchings Paraphrase über den Fund eines Handschuhs.

.jpg)

.jpg)

or Franz von Stuck's (1863-1928 visions of hell and war.

.jpg)

A senseless devastation Germany was repeated time and time again, during so called religious wars, which the East German Werner Tübke's (1929-2004 has depicted through a an immense panorama in Bad Frankenhausen , sometimes referred to as the Sistine Chapel of the North.

or the merciless misery of the post-war period depicted by Otto Dix (1891-1969)

Then the war came back with a vengeance. Worse than ever, with such desperate ferocity that art was no longer sufficient to depict it, although much like Ferlix Nussbaum's art in the Shadow of Death reeks of horror and anguish. He was murdered in 1944 in Auschwitz.

.jpg)

Nussbaum was a helpless victim of Nazism’s brutal mass slaughter. Even before he was wiped out, his art had hinted at what was to come. It is curious that even an artist who eventually joined the Nazi Party practiced a dark, lugubrious art, filled with premonitions of coming disasters.

The Austrian Franz Sedlacek (1891-1945) was connected to an art direction called the New Objectivity. A sharp, detailed art, which through its detached coldness, portrayed a cynically harsh view of humanity. As writtens in Christopher Isherwood’s introduction to his Farewell to Berlin: “ I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking.”

On June 30, 1938, Sedlacek joined the NSDAP and the following year he volunteered in the Second World War. He distinguished himself as a bold front fighter in Norway, as well as in Stalimgrad. Sedlacek escaped unscathed from the Russian hell and re/appeared during the final Polish battles, although he disappeared without a trace during the last months of the war.

.jpg)

In its menacing, compact darkness, Sedlacek’s gloomy art is undeniably fascinating

.jpg)

There is with Sedlacwek a threatening, constant waiting for something – a foreboding of war and misfortune, a gloomy preparation that I also found in some paintinbgs of the Swede Ola Billgren (1940-2001)

.jpg)

and the German Richard Oelze (1900-1980).

.jpg)

The shadows of the war hover compactly above much European art. For example among members of the so-called Vienna School of Fantastic Realism with artists such as Anton Lehmden (1929-2018)

.jpg)

Rudolf Hausner (1914-1995)

.jpeg)

and Arik Brauer (1929-2021)

.jpg)

The decay of Germany's bombed-out cities seems to have been predicted in Monsu Desiderio's (François de Nomé 1593-1620 and Didier Barra 1590-1656) enigmatic cityscapes

.jpg)

and Félicien Rops’s, (1833-1898) syphilis-infected prostitutes.

.jpg)

.jpg)

The concetti of Zuccari’s inner space contains a lot of madness as well.

Several artists have entered there never to return again. Thinking of the Swedish artist Carl Fredrik Hill's (1849-1911) torments.

.jpg)

.jpg)

How he, who was once one of the foremost landscape painters of his time and country, when he was diagnosed with a severer mental illness and began to paint and draw "in his defence" and seemed to want to protect his landscapes in the interior of La Bella Pittura. Her made least four drawings a day and more than 3 000 of them are preserved.

.jpg)

At the same time, the Norwegian landscape painter Lars Herterveg’s (1830-1902) mind darkened and his landscape depictions became increasingly strange.

.jpg)

.jpg)

There are still artists around the world whose perception of reality has been broken and changed after they have stepped into the inner room of their imaginationand often ended locked up within mental hospitals. This happened, for example, to the Norwegian painter Bendik Riss (1911-1988)

.jpg)

.jpg)

and the Dane Luis Marussen (Ovartaci) (1894-1985).

.jpg)

.jpg)

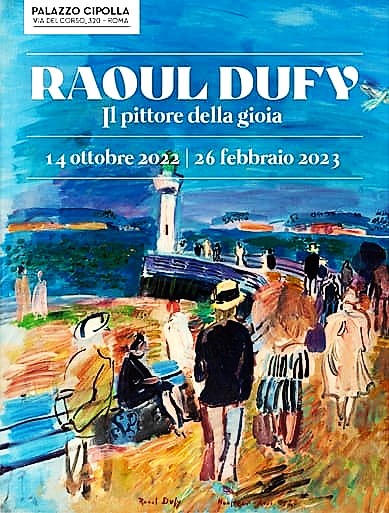

Now let's leave the inner rooms of these broken geniuses and enjoy an example of Raul Dufy's (1877-1953) art. A few days ago I passed a gallery that presented Dufy as Il pittore della gioia. The artist of joy.

I found this to be a true statement. When I got to see Dufy's paintings, I became enlivened and remembered a poster that I had for several years had pinned on the wall in one of my boyhood rooms. It was an advertisement for SNCF, The Société nationale des chemins de fer français, France's national state-owned railway company. It is a dream image of Normandy. How often had I not looked at this summer picture,e with its old house, overgrown garden with inviting garden furniture and a grazing cow. A cyclist passes on a quiet road and along the river steamboats can be glimpsed. Summer peace, warmth and greenery. How many times had I not dreamed myself into that painting?

.jpg)

Bettelheim, Bruno (1975) The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. New York: Vintage Books. Cleri, Bonita (1997) Federico Zuccari: le idee, gli scritti: atti del Convegno di Sant' Angelo in Vado. Milan: Electa.