BY THE GATE OF POETRY: Child sacrifice and Søren Kierkegaard

Like many other children, I experienced what has been called a "devouring age", a kind a bibliomania that in Sweden is said to affect kids between nine and thirteen years of age. I do not know when I was infected by it, though it never abated. As far back as I can remember, I loved looking at pictures. Most of them I unearthed in my grandfather´s bookshelves, treasures like Alfred Brehm's books about animals, the huge book about birds by the Swedish-Finnish von Wright brothers, a lavishly illustrated German edition of the Arabian Nights, Doré's illustrations for the Divina Commedia and Carl Larsson´s for Topelius´ Tales of a Barber-Surgeon, Gödecke´s Viking saga The Tale About Ragnar Lodbrok and His Sons illustrated by Johan Malmström and in particular – William Brassey Hole´s thrilling illustrations in a Bible for Children and Cornelius de Witt´s in a Golden History of the World, as well as many other images to which I repeatedly returned.

Of course I browsed Donald Duck & Co or Hemmets Journal, The Home´s Journal, which one of my sisters bought due to the comic strip Prince Valiant in the Days of King Arthur. In that magazine there were several other comics and glossy trading cards with wild animals, which my other sister gave to me and I gathered in an album. I can still recall their nice smell.

All this viewing of images made me draw and paint long before I started to read. Much of my childhood was spent on sketching and painting, inspired by pictures in the books and magazines I had carefully stuided, hour after hour.

Several children have learned to read before they started school, something that proud parents use to emphasize, but I did not care much about that. For me it was enough to look at pictures and I do not remember when plodding through lines of letters turned into something quite different, when the letters started to connect with each other and images appeared in my mind's eye - a magical reality was created and I fell headlong into parallel worlds where gate after gate was opened, providng access to hitherto unimagined worlds, reminding me about the covers of the book series Min Skattkammare, ”My Treasury”.

.jpg)

There were lots of exciting book series to devour, for example Bonnier´s Publishing House´s red-spined, magnificent selection of youth classics with exquisite illustrations, but also B. Wahlström´s green-spined boys' novels, of which especially Edward S. Ellis Deerfoot novels were the most amazing. When I now read them again I cannot understand how I could not fail to perceive how stilted and strange their language could be and how prejudiced they were.

Nowadays, I also marvel at the fact that I could not perceive any difference between what many adults considered to be "high" and "low" literature. With the same delight and ease I read dime novels about the exploits the flying ace Biggles, Flash Gordon comics, cheap horror novels, as well as unabridged editions of Moby Dick and The Hunchback of Notre Dame. I read with delight Iris Murdoch´s A Severed Head, Camus's The Plague and Faulkner's As I Lay Dying and other novels I found in my father's bookshelf. Novels that any sapient adult would claim was far above the comprehension of a kid like me, an opinion that probably made sense, but I liked those books anyway. In my father's bookshelf I also found The Temptaion of Saint Anthony by Gustave Flaubert, it was a quite strange piece of art, but I became interested and at a book sale I bought his Salammbô and devoured it with the same ravenous appetite as I read The Three Musketeers and The Last of the Mohicans.

Salammbô must be one of Orientalism´s peaks, filled to the brim as it is with all sorts of exotica. It is as if Flaubert endeavoured to cover every page of his novel with descriptions of smells, colours, cruelty and strong emotions of desire, hatred and hunger. Nevertheless, he overcame the difficult challenges he had created for himself. Despite its overloaded extravagance the novel captivates and the images it is conjuring work quite well. Flaubert is a craftsman, a master of language; his settings are alive and breath, they are even more real and tangible than his characters. The images´ baroque exuberance does, strangely enough, not obstruct the flow and rythm of his story telling, or numb the reader's interest. Like in a painting by Gustave Moreau people remain a part of the entire composition, but their incongruity does not become annoying. While writing about Salammbô I came to remember a poem the Swedish poet Nils Ferlin:

Mankind sits by poetry´s gate,

talking about all that´s great,

the marvels she´s done,

the evil she´s shun.

While the sky is blue and the sun is shining

who can then avoid smiling?

Who wants to mock and disturb,

when such marvels are heard?

With Baal and Moloch she´s familiar,

with rituals, horrid and peculiar,

and all that in the night went astray,

and now cry, whimper and pray.

Baal and Moloch are continously present in Salammbô, a novel which revels in blood and violence. An entire chapter is devoted to the sacrifice of children to the insatiable Baal/Moloch. Carthage is under siege from mutinous mercenaries and in their despair its citizens has no other choice but to make the greatest sacrifice that may be required from any human being – they are asked to offer their own children to their tyrannical deity. Even their leader, Hamilcar Barca, is demanded to give up his firstborn son. The Carthaginians gather in the huge square in front Moloch´s temple and the mighty effigy of Moloch, a monstrosity that also serves as an oven, is rolled out:

Part of a wall in the temple of Moloch was thrown down in order to draw out the brazen god without touching the ashes of the altar. Then as soon as the sun appeared the hierodules pushed it towards the square of Khamon. It moved backwards sliding upon cylinders; its shoulders overlapped the walls.

Page after page provides detailed descriptions of how huge effigies are brought out from other temples, one after the other, engulfed by clouds of incense and accompanied by lavishly attired temple servants are they brought into the central square and placed around the Baal/Moloch:

At last the Baal arrived exactly in the centre of the square. His pontiffs arranged an enclosure with trellis-work to keep of the multitude, and remained around him at his feet.

Groups of priests serving the various deities placed themelves in different groups around the bronze colossus. Flaubert excels in descriptions of their costumes, ornaments, hymns and ceremonies. The mood of the assembled crowd is whipped up, hysteria spreads in waves back and forth through the assembled crowd:

An individual sacrifice was necessary, a perfectly voluntary oblation, which was considered as carrying the others along with it. But no one had appeared up to the present, and the seven passages leading from the barriers to the colossus were completely empty. Then the priests, to encourage the people, drew bodkins from their girdles and gashed their faces. The Devotees, who were stretched on the ground outside, were brought within the enclosure. A bundle of horrible irons was thrown to them, and each chose his own torture. They drove in spits between their breasts; they split their cheeks; they put crowns of thorns upon their heads; then they twined their arms together, and surrounded the children in another large circle which widened and contracted in turns. They reached to the balustrade, they threw themselves back again, and then began once more, attracting the crowd to them by the dizziness of their motion with its accompanying blood and shrieks.

By degrees people came into the end of the passages; they flung into the flames pearls, gold vases, cups, torches, all their wealth; the offerings became constantly more numerous and more splendid. At last a man who tottered, a man pale and hideous with terror, thrust forward a child; then a little black mass was seen between the hands of the colossus, and sank into the dark opening. The priests bent over the edge of the great flagstone, — and a new song burst forth celebrating the joys of death and of new birth into eternity.

The children ascended slowly, and as the smoke formed lofty eddies as it escaped, they seemed at a distance to disappear in a cloud. Not one stirred. Their wrists and ankles were tied, and the dark drapery prevented them from seeing anything and from being recognised.

The children are placed in the enormuos bronze effigy´s hands and its arms are then raised by priests who pull chains to lift them up towards Baal/Moloch´s gaping, gargantuan jaw from which flames fan out:

The brazen arms were working more quickly. They paused no longer. Every time that a child was placed in them the priests of Moloch spread out their hands upon him to burden him with the crimes of the people, vocifering: ”They are not men but oxen!” and the multitude round about repeated: ”Oxen! Oxen!” The devout exclaimed: ”Lord! Eat!” […]

The victims, when scarcely at the edge of the opening, disappeared like a drop of water on a red-hot plate, and white smoke rose amid the great scarlet colour.

Nevertheless, the appetite of the god was not appeased. He ever wished for more. In order to furnish him with a larger supply, the victims were piled up on his hands with a big chain above them which kept them in their place. Some devout persons had at the beginning wished to count them, to see whether their number corresponded with the days of the solar year; but others were brought, and it was impossible to distinguish them in the giddy motion of the horrible arms. This lasted for a long, indefinite time until the evening. Then the partitions inside assumed a darker glow, and burning flesh could be seen. Some even believed that they could discern hair, limbs, and whole bodies.

Baal/Moloch was obviously the most heinous idol imaginable. To bestow well-being and favours on his worshippers he demanded the renunciation of what ought be the most essential duty of every human being on earth, what all living beings appear to be have been destined for, namely to safeguard and protect their offspring. Fearsome creatures protect their children and are ready to die for them. As soon as their progeny come out of their eggs, the female crocodile watches over them. The scorpion mother carries her children on her back, shading them with her uplifted abdomen and protects them with her bulbous sting, inflated with poison. Though, we humans have sacrificed our children to imaginary beings. The Roman writer Diodorus Siculus wrote about the Carthagians:

There was in their city a bronze image of Cronus, extending its hands, palms up and sloping toward the ground, so that each of the children when placed thereon rolled down and fell into a sort of gaping pit filled with fire.

Siculus says that high-born children's relatives were forbidden to weep during the terrible sacrificial ceremonies. Long before had a commentator to Plato's Republic written:

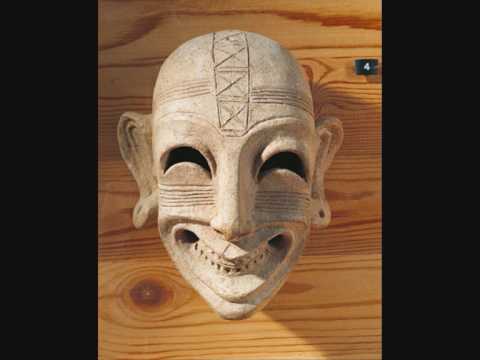

There stands in their midst a bronze statue of Kronos, its hands extended over a bronze brazier, the flames of which engulf the child. When the flames fall upon the body, the limbs contract and the open mouth seems almost to be laughing until the contracted body slips quietly into the brazier. Thus it is that the ”grin” is known as ”sardonic laufghter”, since they die laughing.

The term "sardonic laughter" is mentioned already in the Odyssey and originates from Sardinia. The Carthaginians exercised during Classical times a great influence on the island. The Sardes did during the Punic Wars ally themselves with the Carthaginians against the Romans and throughout time they had taken over some of the Punic customs. The Russian folklorist Vladimir Propp explains the origin of the word "sardonic":

Among the very ancient people of Sardinia, who were called Sardi or Sardoni, it was customary to kill old people. While killing their old people, the Sardi laughed loudly. This is the origin of notorious sardonic laughter, now meaning cruel, malicious laughter. In light of our findings things begin to look different. Laughter accompanies the passage from death to life; it creates life and accompanies birth. Consequently, laughter accompanying killing transforms death into a new birth, nullifies murder as such, and is an act of piety that transforms death into a new life.

It may seem to be a strange coincidence that the sardonically grinning mask above, from the fifth century B.C., is exhibited in the Bardo Museum in Tunis, where three terrorists on the 18th of March 2015 in the name of God massacred 21 people and wounded fifty.

Is the bestial murder of children unusual? Not at all. Only seventy-five years ago, the Nazi regime's faithful servants systematically murdered and burned hundreds of thousands of children. Sacrificed for what? For better harvests, rain and the wellbeing of fellow human beings? Not at all - for conservation of the purity of race! Can a more brain-dead defense of mass murder of children be imagined? A more grotesque denial of human dignity? A more senseless defense defense for criminal acts? In his infamous speech to party officials in Poznan, in occupied Poland, on October 6, 1943, Heinrich Himmler defended the mass murders of Jewish women and children:

I ask of you that which I say to you in this circle be really only heard and not ever discussed. We were faced with the question: what about the women and children? – I decided to find a clear solution to this problem too. I did not consider myself justified to exterminate the men – in other words, to kill them or have them killed and allow the avengers of our sons and grandsons in the form of their children to grow up. The difficult decision had to be made to have this people disappear from the earth. For the organisation which had to execute this task, it was the most difficult which we had ever had.

To the conscious and planned murder of Jewish children can be added the equally well-planned assassinations of Romani children, as well as the executions of German children considered to be retarded. In a few yers time more than one and a half million children were systematically exterminated. What is more natural than becoming saddened and furious about murder, abuse and mistreatment of children? Are we humans worse than scorpions and crocodiles?

A lot of sickening abuse of innocent children and other defenseless people have been, and is currently, commited in the name of religion; to honour and appease phantoms whose existence is, to put it mildly, questionable. A shocking memory of mine is when I a few years ago at Mexico's National Museum saw cages that had enclosed children who at Aztec markets had been sold to be sacrificed to the rain god Tlaloc. Why? For your own or your community´s wellbeing. Is there anything more grotesque than to induce human suffering with an intent to appease something/someone whose existence cannot be proved, something the Islamic State currently is engaged with.

Baal and Molech have been serving as symbols for the crazy, callous exploitation and sacrifice of our fellow human beings. Flaubert's torrid vision of an exotic, lush, seductive and child sacrificing ancient empire became violently appreciated when his novel was published in 1862 and it immediately gave rise to plagiarism, at the same time as it inspired various works of art; paintings, dramas, ballets, operas, and later on - movies like the Italian Cabiria or Griffith's Intolerance, to name but a few.

The human-devouring Moloch would be soon become, as in Fritz Lang's Metropolis, a symbol of the ruthless capitalist system, or its communist counterpart - the totalitarian state. In his admired and indicted, for violating decency, beat poem Howl Allen Ginsberg furiously devoted page after page to depict the US as a huge, man-devouring, soulless Moloch:

Moloch! Solitude! Filth! Ugliness! Ashcans and unobtainable dollars! Children screaming under the stairways! Boys sobbing in armies! Old men weeping in the parks!

Moloch! Moloch! Nightmare of Moloch! Moloch the loveless! Mental Moloch! Moloch the heavy judger of men!

Moloch the incomprehensible prison! Moloch the crossbone soulless jailhouse and Congress of sorrows! Moloch whose buildings are judgment! Moloch the vast stone of war! Moloch the stunned governments!

Moloch whose mind is pure machinery! Moloch whose blood is running money! Moloch whose fingers are ten armies! Moloch whose breast is a cannibal dynamo! Moloch whose ear is a smoking tomb!

Moloch whose eyes are a thousand blind windows! Moloch whose skyscrapers stand in the long streets like endless Jehovahs! Moloch whose factories dream and croak in the fog! Moloch whose smoke-stacks and antennae crown the cities!

Eventually Moloch´s presence in books and film has thinned out, perhaps due to the fact that huge exhaust and fire spewing industries are gradually disappearing from our lives and our minds, or surviving as stinking, pathetic remnants of their ancient glory. Like the Lucchini Group´s steel plant, which produces railway tracks in the Tuscan coastal town of Piombino. An environment depicted in Silvia Avallone´s debut novel Swimming to Elba, which makes its disillusioned workers and their depressing surroundings into a symbol of hopelessness and moral decay in today's Italy. Once the steel plant employed more than 20,000 workers, who worked and toiled with blast furnaces, cranes and trucks, but also attended union meetings, studying Marx and waving red flags. Now most of them fear losing their jobs, while some are stuck with drugs and alcohol.

Aside from legends and symbols - has terrible creations as Baal and Molech really existed? They are several times mentioned in the Old Testament and seem originally to have been Caananite fertility deities. Like the Israelites, Canaanites spoke a Semitic language and it is very possible that the two peoples had a common origin, although Caanaites would later correspond to the Phoenicians and Israelites to Jews. Baal is ”master” in Caananite, while Moloch, or Melech, was eqivalent of ”king”.

It was the Phoenicians who founded Carthage and they took their gods with them. For more than a century (264-146 BC) the Carthaginians, or the Punics as the Romans called them, the Roman Republic's most dangerous opponents. Ancient Romans and Greeks regarded the Punics as religious fanatics who regularly sacrificed child to Baal Hammon and Molech, by Greeks and Romans called Kronos, the ancient god of Greek mythology who devoured his own children.

However, no archaeological remains indicate that in Carthage, or any other place for that matter, there ever existed a huge idol with a bull's head, which was actually an oven, and built to devour and incinerate living children. What archaeological excavations have exhumed in Carthage is a large temple area, only a few meters from the remains of the Carthaginian Cothon, harbor, which consisted of a huge circular and walled, hundred meters wide canal, serving as a berth for both war and merchant ships.

Within the remnants of the temple area were thousands of buried urns containing the burnt residue of children. Many of these graves were marked with simple stone pillars, and from inscriptions on some of them it can be grasped that the cemetery was called Topheth, which the Israelis named a place outside Jerusalem, infamous for in bygone times having been a site for child sacrifices.

In the book of Isaiah there is a curse on the Assyrian king, suggesting that peopl were sacrificed in a place called Topheth:

For a burning place has long been prepared; indeed, for the king it is made ready, its pyre made deep and wide, with fire and wood in abundance; the breath of the LORD, like a stream of sulfur, kindles it.

On several of the pillar found in Carthage the Punic letters MLK were inscrfibed, which apparently in this particular context can be interpreted as "victims". In Hebrew, the MLK "מלך" letter combination only occurs in the sense "to bring children through the fire (lmlk)". A concept that seems to imply a sacrifice which in Hebrew was called (h)olokautoma, burnt offering. The Greek translated it as ὁλόκαυστος (holókaustos) where holos, meant "whole" and kaustós, "burned". This meant that sacrificial animals on an altar were burnt to ashes. It is thus possible that the MLK of the Phoenicians of Carthage was not the name of a god, but just indicated that someone, or something, had been sacrificed, lmlk (brought through fire), to a god, probably Baal, their supreme god who appeared in several of their leaders´ names such as Hannibal, "Favoured by Baal."

In the Bible, Baal is referred to as a "false divinity", a competitor to the Israelite´s Yahweh. For example, in the First Kings of the Bible, the prophets of Baal are challenged to a contest by the Prophet Elijah:

Elijah went before the people and said, “How long will you waver between two opinions? If the Lord is God, follow him; but if Baal is God, follow him.”

But the people said nothing.

Then Elijah said to them, “I am the only one of the Lord’s prophets left, but Baal has four hundred and fifty prophets. Let two bulls for us. Let Baal’s prophets choose one for themselves, and let them cut it into pieces and put it on the wood but not set fire to it. I will prepare the other bull and put it on the wood but not set fire to it. Then you call on the name of your god, and I will call on the name of the Lord. The god who answers by fire—he is God.”

Elijah won the competition; God ignited his sacrifice but not the one of the prophets of Baal.

When all the people saw this, they fell prostrate and cried, “The Lord—he is God! The Lord — he is God!”

Then Elijah commanded them, “Seize the prophets of Baal. Don’t let anyone get away!” They seized them, and Elijah had them brought down to the Kishon Valley and slaughtered them there.

At several places in the Bible, Baal worshippers are accused of being child slayers. Nevertheless, Abraham, whose name means " father of many”, Hebrew patriarch and founder of the three monotheistic religions - Judaism, Christianity and Islam, was once ordered by God to slaughter a his only son (a former son, Ishmael, had by Abraham been exiled into the desert and probably assumed dead). God's command suggests the Canaanite belief in the necessity child victims, a belief that the Israelis once again seem to have shared. One of the laws mentioned in Exodus stated: " “Consecrate to me every firstborn male. The first offspring of every womb among the Israelites belongs to me, whether human or animal.” God´s demand to Abraham indicates that not even the old patriarch was exempted from this harsh rule:

“Take your son, your only son, whom you love—Isaac—and go to the region of Moriah. Sacrifice him there as a burnt offering on a mountain I will show you.”

Early the next morning Abraham got up and loaded his donkey. He took with him two of his servants and his son Isaac. When he had cut enough wood for the burnt offering, he set out for the place God had told him about. On the third day Abraham looked up and saw the place in the distance. He said to his servants, “Stay here with the donkey while I and the boy go over there. We will worship and then we will come back to you.”

Abraham took the wood for the burnt offering and placed it on his son Isaac,and he himself carried the fire and the knife. As the two of them went on together, Isaac spoke up and said to his father Abraham, “Father?”

“Yes, my son?” Abraham replied.

“The fire and wood are here,” Isaac said, “but where is the lamb for the burnt offering?”

Abraham answered, “God himself will provide the lamb for the burnt offering, my son.” And the two of them went on together.

When they reached the place God had told him about, Abraham built an altarthere and arranged the wood on it. He bound his son Isaac and laid him on the altar, on top of the wood. Then he reached out his hand and took the knife to slay his son. But the angel of the Lord called out to him from heaven,“Abraham! Abraham!”

“Here I am,” he replied.

“Do not lay a hand on the boy,” he said. “Do not do anything to him. Now I know that you fear God, because you have not withheld from me your son, your only son.”

The story tells how God from a deeply religious man requires an inexplicable atrocitiy - an infanticide. And it is not any child God is asking for. It was Abraham´s only son, whom he received in his old age, whom he loved above all else and the meaning and goal of his entire existence.

Within Orthodox Judaism there are many believers who do not attach great importance to a personal life after death; they regard their children as threir continued existence, as "a divine trust, the only guarantee for future and survival." In accordance with such a view parents are considered to be preservers on life on earth, God's co-workers in the creation of every single human being. Thus infanticide is a terrible act, a crime against the survival of humanity. Had Abraham, ancestor to all Jews and Arabs, killed his son Judaism would not have existed. Therefore, the command of God to spare Isaac is regarded as the foundation of Judaism as a religion separate from the Canaanite faith. If God was previously all peoples´ God, his sparing of Abraham's son carries a special meaning to the Jews, they became God's "peculiar people" and because of this is the sacrifice of children by them rearded as particularly abominable.

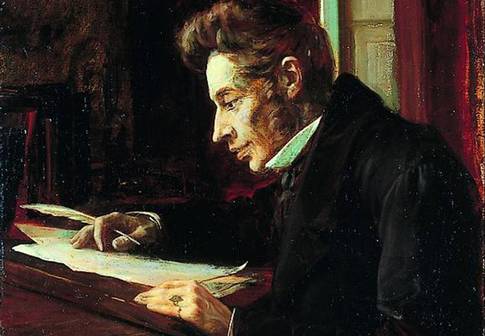

Someone who did not consider Abraham's intended sacrifice in this abstract manner, was the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard. He was upset by the Bible´s tale about Abraham's sacrifice, partly because he regarded his deeply religious and melancholically inclined father to be someone who for his distorted faith had sacrificed his son to God, and thus had aggravated the entire existence of his offspring. Kierkegaard mantained a lifelong struggle against what he considered to be people's mindless acceptance of truths and dogmas. To live a "real life" meant according to Kierkegaard to constantly question our opinions, our own lives and behaviour. Are we raeally thinking? Or are most of us like dumb creatures who are just following the flock, doing what others do? ”Life is not a problem to be solved, but a reality to be experienced.”

Kierkegaard's book on Abraham's sacrifice, Fear And Trembling, is one of the strangest books have I read. It is far from light reading. It reminds me of a very long sermon delivered by an intelligent priest. The more or less one hundred pages long book is well written, exposing humour and thought-provoking ideas. In the middle of it we find a brilliant depiction of the natue of infatuation. However, time after time I became lost and was struck by fatigue and difficulties in following the text, missing the points the author makes and even nod off.

Nevertheless, the beauty of Kierkegaard's sermon is that it is available in book form. When I after a short nap return to the section tha anesthetized me I once again alterted, finding new gems in text.

Fear and Trembling is about life, filled with sharp observations and deep insights and it's amazing that was written by a hermit who experienced only one great love in his life, which he deliberately withdrew from and that came to overshadow his entire existence. Kierkegaard reminds me of Jules Verne, whose life also was marked by an interrupted love story, with a youth overshadowed by a dominant father and who finally, depressed and grumpy, spent most of his time writing detailed and amazing stories about adventures in places he had never visited and experiences he never had. Towards the end of his life, Jules Verne wrote to his brother: "I now live only to work."

Kierkegaard abhorred the philosophy of the popular German philospher Friedrich Hegel, which he considered to be an invention of unwavering rules, valid for all and sundry. A life-lie. That when a herebrained creature accepted all what he heard from the Danish pulpits, or in the writings of dogmatic philosophers, such as Hegel, would be the same as giving up her/his dignity and ability to think independently: ”You may easily imagine a logical system, but you cannot imagine a system behind your own existence.” Kirkegaard was well aware of the fact that any ideological construction of what it means to be human inevitable leads to gross generalizations: ”The more understanding increases, the more it becomes a kind of inhuman understanding”. We are all imperfect human beings.

According to Kierkegaard dedicated philosophers, like Hegel, are building castles in the air, they assume the existence of fixed patterns of existence and induce their readers into the conviction that they are actually describing ”the reality”. Hegel makes his followers believe that his imaginary system is for real. "One question that always eluded Hegel was - how should you live? It is like a reading a cookbook aloud to a hungry man.”

Writing means conjuring up a world to the reader. An author is like an actor performing various roles that the spectator may recognise, or even identify with. Kierkegaard, who was an ardent visitor to the theatres, wrote his philosophical reflections under various pseudonyms. He played roles which he called Constantin Constantinus, Frater Taciturnus, Hilarius Bookbinder, John Climacus, John the Seducer, Nicolaus Nota Bene, Victor Eremita, etc. It is John di silentio, "John of silence", who writes Fear and Trembling in which he calls Abraham a "knight of faith" and thus seems to imply that the old patriarch´s intent to abide to God's command to sacrifice his own son was an admirable decision.

Is Kierkegaard in the guise of John the silentio celebrating religious fanaticism? He claims that religious belief is absurd, that it has nothing to do with science and logic. Faith is according to Kierkegaard, an inexplicable mystery: "Faith begins where thought comes to a standstill." Nevertheless, to sacrifice other people for something that in reality is incomprehensible and absurd, can such acts be justified? Suicide bombers and fanatical warriors poisoned by the braindead ideology of IS. People who slaughter their fellow human beings in the name of a distorted belief, can such people be hailed as "knights of faith"?

After reading Fear and Trembling I have to return to it again, trying to read this strange book in the light of Kierkegaard's expressed standpoint, his interpretation of what he calls objective and subjective thinking. When I endeavour to do just that, the book begins to work for me.

Kierkegaard did not waste many comments on the story's happy ending, namely that God, at the moment when Abraham raises his knife to sacrifice his son, is preventing the slaughter, commanding his loyal minion to sacrifice a ram instead, thus transforming the entire episode to a parable intended to put an end to child sacrifies. God´s heinous command is thus turned into some kind of practical joke designed to test the faith of Abraham.

Instead of concntrating on this rather dubious moral – that God tests us to find out if our faith is sincere or not - Kierkegaard concentrates on depicting Abraham's anguish, his loneliness, ruminations and considerations during his three-day donkey ride towards the mount of Moriah, where Abraham, unknown to his kin and in violation of all that fatherhood implies will slaughter his son. During his jorney Abraham finds himself in a limbo; vulnerable and alone with his doubts, he has ended up outside human society. Life has lost its obviousness. Abraham is no longer a leader of his people, but an "emigrant from the public sphere". Kierkegaard, or rather John the silentio hints att the fact be that behind every action, or failure to act, there is a choice.¨

In something appearing as a state of shock that John de silentio tells the story of Abraham. The patriarch´s behaviour is a mystery to him. Either is Abraham's act an attempt at cold-blooded murder or as it is presented from the Danish church pulpits - a mighty deed reflecting a steadfast belief in the logic and love of God´s decisions. Abraham submits himself to God's command, even if it implies a violation of his innnermost feelings and his duty as a committed father. Furthermore - it is a abominable crime against human laws.

What if God in the last minute had not changed his gory command? John the silentio provides us with the example of how a priest's inspiring and fiery sermon about Abraham's admirable submission to God's will is impressing an attentively listening father, who after church goes home and kills his beloved son. Would such an act not be tantamount to an abominable crime based on the irresponsible behavior of a Danish priest who has sworn allegiance to a State that intends to protect its citizens´ lives?

Kierkegaard avoids any kind of definitive statement, hiding behind the persona of John the silentio, who describes himself as a "faithless poet", i.e. an artist who creates an image while depicting a problem, a truth. Nothing more, nothing less.

The subjective thinker is not a scientist-scholar; he is an artist. To exist is an art. The subjective thinker is esthetic enough for his life to have esthetic content, ethical enough to regulate it, dialectical enough in thinking to master it. The subjective thinker’s task is to understand himself in existence. … To understand oneself in existence is the Christian principle, except that this self has received much richer and much more profound qualifications that are even more difficult to understand together with existing.

Through his woks of art an artist invites viewers to form their own opinion about what is described. An honest arist is, as close as possible to what he perecives to be the reality, trying to account for every detail that may form the basis for an unpredjudiced judgment. John the silentio writes of Shakespeare, stating that the great playwright "says everything, everything, everything exactly as it is", but that does not mean that Shakespeare is identical with what he describes, or share the views he presentss. Shakespeare is like John the silentio a poet.

Another of Kierkegaard´s many aliases, John Climacus, wrote what Kierkegaard called a Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, A Mimical-Pathetic-Dialectical Compilation an Existential Contribution. John Climacus made a difference between "having faith" and "understanding faith". Understanding faith is not the same thing as "coming into it."

As a poet, John the silentio is able to detach himself from his own tale and judgements. For sure, he depicts Abraham's dilemma and even claim to have understood his actions, but that does not mean that Johnnes would be able to act in the same way. At the end of his exposé of Abraham´s act of faith, Johannes de silentio claims that he personally would be utterly unable to act like Abraham. The behaviour of the patriarch might have been the ultimate consequence of a true religious conviction, but it is an incomprehensible way of being - it would mean that a person acting like that would detach himself from the realm of the living.

But before coming to such a conclusion, John di silentio has praised Abraham's behavior as a bold act of surrender to something he believes to be much greater than himself and because this power is infinite, it is also incomprehensible for human imagination and thus it cannot be grasped by our finite mind – Abraham´s behaviour is based on faith, a phenomenon beyond any legal framework and average comprehension. To behave responsibly towards the power we believe to be God demands an abandonment of the law-defined ethics that govern our relationship to fellow citizens. Religious fanaticism will distance us from everyday life, leading us into loneliness and the outrageous demands on any individual who has dared to make such a choice. Here we find, for example, Jesus' anguish in Gethsemane, before he decides to sacrifice himself for his faith. To believe is to make yourself receptive to something completely new, unknown, and quite different from what is demanded by common law and order.

However, and this is important to emphasize, Jesus' actions did not include the sacrifice of another human being for his faith, insted he sacrificed himself. Jesus´ decision was based on compassion and a belief in the saving power of empathy, which is at the very core of Christianity. Abraham´s intended to sacrifice another being, an innocent child - a repulsive act. Thankfully, God finally demonstrated his compassion, otherwise he would have remained the same as in ancient times – a Baal and a Moloch, an incomprehensible being, indescribable in his limitless cruelty. If Abraham had killed his son, he had behaved in the same way as fanatics who sacrifice their loved ones in the service of an insensitive, made-up ideology. It is such an unreasoning faith that Kierkegaard constantly turns against – the acceptance of a system that ignores an individual's ability to make decisons based on hers/his own unique reflections.

In an article dealing with Communism´s hostility towards imagigantion the Nobel laureate Mario Vargas Llosa quotes the French writer and philosopher Georges Bataille:

Apparently, effective activity, raised to the discipline of a systen based on reason, which is Communism, is the solution to every problem. But it cannot either condemn completely, or tolerate in practice, the purely autonomous, sovereign attitude by which the present moment is detached from all the other moments that will come later. This presents a great difficulty for a party which only respects reason, and which cannot see in irrational values – through which the abundant, useless and infantile aspects of life are born – anything beyond the particular interest they comceal. The only soverign attitude admitted within the framework of Communism, albeit in a minor way, is that of a child. It is accpted that children cannot aspire to the seriousness of an adult. But an adult who gives a primoridal meaning to the infantile, who engages with literaature as if he was dealing with a supreme value, has no place in Communist society.

To kill and torture children is a way of denying our own childishness, as well as our fundamental responsibility as living creatures; our duty to protect our offspring and guarantee them a secure future, it is thus a denial of our own humanity.

People were also bringing babies to Jesus for him to place his hands on them. When the disciples saw this, they rebuked them. But Jesus called the children to him and said, “Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these. Truly I tell you, anyone who will not receive the kingdom of God like a little child will never enter it.”

Avallone, Silvia (2012) Swimming to Elba. New York: Viking/Peguin. Costello, Peter (1978) Jules Verne: Inventor of Science Fiction. New York: Scribner. Flaubert, Gustave (1977) Salammbo. London: Penguin Classics. Ginsberg, Allen (2013) Howl, Kaddish and Other Poems. London: Penguin Modern Classics. Kierkegaard, Søren (1992) Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments, A Mimical-Pathetic-Dialectical Compilation an Existential Contribution Volume I, by Johannes Climacus, edited by Soren Kierkegaard. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Kierkegaard, Søren (1985) Fear and Trembling. London: Penguin Classics. Levenson, Jon D. (1975) The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son: The Transformation of Child Sacrifice in Judaism and Christianity. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Longerich, Peter (2012) Heinrich Himmler. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Martin, Jacques (1993) Alix, tome 8: Le Tombeau Étrusque. Tournai: Casterman. Propp, Vladimir (1984) Theory and History of Folklore. Manchester: Manchester University Press. Vargas Llosa, Mario (1996) ”Bataille or the Redemption of Evil", in Making Waves: Essays.New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux. Warmington, Brian Herbert (1960) Carthage. Harmondsworth: Pelican Books.