ECCO LA PRIMAVERA; Meeting the spring and Machiavell

During Easter holidays I, Rose and Esmeralda spent a few days in a picturesque stone house situated on a wooded hillside within a village of a dozen houses. The place was called Mezzanelli and was set amongst the Umbrian hills south of Perugia. Good friends had lent us their centuries-old house, which provided an archaic impression, even if it had been completely renovated. It was intimate and comfortable, with small rooms though with three stories and a large fireplace. It had been constructed with sturdy stone blocks, the floors were of polished stone, while rough-hewn oak beams were holding up the ceilings and the roof, with its panheaded tiles. A terraced garden flaunted a host of blue fleures-de-lis under grey crowns of twisted olive trees.

Above the house were a church and the ruins of a castle with a huge, crumbling tower that still dominated the landscape. Among thorns and boulders I and Esmerakda climbed the steep hill up to the tower. The castle had first been mentioned in a document from the 1100s and had apparently once guarded a now vanished road between Todi and Spoleto, something that had meant that it had repeatedly been besieged by ever-changing enemy forces. Eventually the entire castle had been demolished in the year 1500 after a local count had been defeated by troops that served under the infamous Pope Alexander VI.

Data about the castle were not easily found - the village of Mezzanelli and its castle are hardly known outside their community and rarely found on any map.

From the garden we could look out over the rolling hills of the Umbrian countryside; with forests, wine covered slopes and spiky cypresses, far away blending into bluish mountain ranges. Swallows whooshed through the air and since the house was high up we could see lots of small birds, thrushes and doves among the tree tops below us.

We had breakfast and lunch with olives, wine, cheese and prosciutto in a rose arbor overlooking the spring fresh Umbrian greenery. As in Francesco Landini´s charming madrigal written in the 1370s:

Ecco la primavera,

Che'l cor fa rallegrare,

Temp'è d'annamorare

E stands con lieta Cera.

Noi vegiam l'aria e'l tempo

Che pur Chiam 'allegria

In questo Vago tempo

Ogni cosa vagheça.

L'Erbe con spruce frescheça

E fior 'coprono in Prati,

E gli Albori adornati

Sono into Simil manera.

Ecco la primavera

Che'l cor fa rallegrare

Temp'è d'annamorare

E stands con lieta Cera.

Behold the spring

Bringing joy to the heart

Time to fall in love

And be happy.

The air and mild weather

Beckon pure and simple joy

During this lively time

When everything wakes up.

When cool freshness of green grass

And flowers cover the meadows

Adorning the trees

In a similar manner.

Behold the spring

Bringing joy to the heart.

Time to fall in love

And be happy.

One evening we went down to a trattoria housed in an old water mill - Il Vecchio Molino. A rustic place where a huge fire blazed. We were the only guests, except for some old men playing cards at one table and at another were two friends enjoying a three meal course meal in comapany with a little girl, who was the granddaughter of the inn keeper. We drank full-bodied, tasty wine, while I ate a delicious pappardelle al ragù di cinghiale, pasta with wild boar ragout. Rose and Esmeralda were content with a lighter dish.

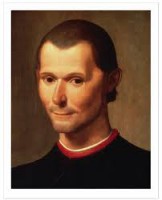

Sometimes it may seem as if books are finding you and not the other way around. When I had come back to Hässleholm after my delightful visit to Italy I did as usual pay a visit to the public library, something I do almost every day, since it is not far from school, there I found a book with Niccolò Machiavelli's letters to his friends. Back home I read a letter that Machiavelli on November 23, 1513 wrote to his friend Francesco Vettori, the Florentine ambassador at Rome´s papal court.

Machiavelli was deeply depressed. After fourteen years as Vice Chancellor of the Florentine State Administration, with primary responsibility for the army's financing, as well as being the Republic's foremost ambassador, Machiavelli had been deposed from office. Not only that - he was forbidden to leave the city, at the same time as he was denied access to Pallazzo Vecchio, the political power center. The ousted chancellor who had thrived in the political hot air now walked the streets of his beloved Florence, feeling like an exhausted failure. In another of his letters he quoted a sonnet by Petrarch:

Therefore if sometimes I should laugh or sing,

It is because there is no other way

My eyes can let go of these tears that sting.

And worse is to come. By former colleagues in the civil service, several of whom he had supported and taught, Machiavelli was summoned to Pallazzo Vecchio to account for every single florin he had managed and spent during his long tenure as chancellor. The thorough investigation went on for months, but in the end it had to be admitted that the eminent bureaucrat had served the Republic with impeccable integrity.

Machiavelli had been ruthlessly attacked since he had with heart and soul supported the overthrown Gonfaloniere of the Republic, i.e. the head of the Signoria, Florence´s Government - Pier Soderini. According to Machiavelli, Soderini was a patient and kind-hearted man, but thereby also too weak and indecisive to be the strong leader Florence needed. From being admired, even loved, Soderini finally ended up as a "lonely and frightened" man. His vacillations had triggered the ruthless sack of the town of Prato, when starving Spanish and Swiss mercenaries massacred more than four thousand men, women and children and afterwards unthreatened continued their march towards Florence, which horrified citizens capitulated to the fearsome and bloodthirsty enemy power.

Machiavelli could never forgive Soderini for transforming goodness to incapacity and hopelessness. If acting in the manner of a true statesman, Soderini ought to have behaved both as a brave lion and a cunning fox. After mercenaries had secured their hometown for them the Medicis could return to power, while Machiavelli's star sank - no, it plummeted. Hardly had he been acquitted from the charge of having embezzled State funds than a few disgruntled young men, who had tried to organize a conspiracy against the Medici, were arrested by the new regime. On one of them was found a list of prospective supporters of the planned coup, among them - Niccolò Machiavelli.

"I am who I am," he explained, "but have not been part of any such conspiracy." His opponents did not give in, in order to obtain a confession the new authorities decided to "expose him to the rope". Tortura della fune, torture with the cord, or as it is also was called degli strappi di corda, tug of the rope, was executed in the following manner - the prisoner's hands were tied behind his back after which a rope hoisted him up with the help of a wheel and a pulley, then he was left falling headlong to the floor, only to be stopped with a hard jerk before he hit it. A very painful process that could dislodge the arm joints from their mountings.

The forty-three years old Machiavelli was subjected to six strappi and even though he was injured, he was to his own surprise refusing to admit any wrongdoing. When he afterwards was left in his cell he woke up the following morning heariing the songs of the comforting Holy Brethren who were accompanying the sentenced young men to the gibbet. Machiavelli decided to write a sonnet to the Medicis asking for his own pardon, it ended contained the words:

What annoyed me most

Was that, as I had fallen asleep, towards dawn

I heard saying in songs – We are praying for you

Now, to hell with it!

On condition that your piety turns towards me

Good Father, and unties these chains.

His words do not express any pity for the fate of those condemned to beheading, only an intention to demonstrate for the Medicis that he himself remained the same man as before his imprisonment - strong, determined and innocent of any crime. Not an overly pious man, but someone who wanted to save his life on this earth, the only kind of life he was interested in.

Unable to crack Machiavelli, the Medicis pardoned him when spring came. He was released from prison on March 12th and stumbled out from his cell, rough-mannered and tired, but in a relatively good mood he headed directly to his home village, the little Sant'Andrea in Percussina two miles from Florence, where his wife Marietta, their five children and several close relatives were waiting for him. In Sant'Andrea, Machiavelli owned a stone house, some olive groves and above all woodland.

Machiavelli was surprised that he had been able to endure so much misery and "yet remain myself". Without false modesty, he wrote to a friend:

... I desire you may find pleasure at the thought that I withstood my torments so boldly that I am proud of myself, I behaved better than I could believe.

In the letter mentioned above, which he wrote to his friend the ambassador Francesco Vettori, Machiavelli complained about his miserable existence:

I can only tell you in this letter of mine what my life is like, wishing to match favor with favor, and if you think you would like to exchange yours for mine, I would be very happy to do so.

Machiavelli's letter was written in response to a letter in which Vettori had told him about his life in Rome. Vettori complained that he did not get so much done, writing that:

Mornings, these days, I get up at ten o´clock and after dressing, I go over to the palace; not every morning, however, but once out of every two or three, There, on occasion, I speak twenty words with the pope, ten with Cardinal de Medici, six with Giuliano the Maginificent; and if I cannot speak with him, I speak with Piero Aedinghelli, then with whatever ambassadors happen to be in those chambers; and I hear a thing or two, though little or any moment.

That Vettori claimed to be not so particularly influential might possibly be because Machiavelli was trying to enter the power sphere around the Medici Pope and wanted Vettori to put in a good word for him wherever he could do it.

Above all, Machiavelli wanted his friend to interest the Medici in the "little book" he had written during his time in Sant'Andrea in Percussina. He called it De Principatibus, About Principalities, but it would soon throughout the world become known as Il Principe, The Prince. Far from being shy, Machiavelli was convinced that if the Medici found the opportunity to read his book they would for certain be interested in making use of his knowledge and services: "Everyone should be eager to take advantage of someone who has been able to gather so much experience from others." He dedicated his book to Pope Leo X's nephew Lorenzo de Medici, who was now the political leader of Florence and accordingly one of those who previously had treated Machiavelli so bad and unfairly. Nevertheless, he had come to regard the Medicis as the only ones whose sponsorship would enable him to regain his influence on Florence's political life. When Francesco Vettori long last managed to hand over Il Principe to Lorenzo de Medici, he appeared to be much more interested in the question of which of his dogs that would the most suitable for pairing with a handsome greyhound he had received as a gift at the same occasion. Machiavelli was desperate:

So I am going to stay just as I am amid my lice, unable to find any man who recalls my service or believes I might be good for anything. But I cannot possibly go on like this for long, because I am rotting away ...

He compared his miserable existence with Francesco Vettori´s Roman life. His friend lived in a large house not far from the Vatican, with nine servants, a chaplain – since Vettori was a very pious man who would attend Mass every day - a secretary, a stable with seven horses and elegant carriages. Sometimes he invited guests to dinner, with three or four dishes. He visited the Pope's residence, not every day, but every other and inquired about political developments while he mingled with the large throng of adventurers who flocked around Leo X. The evenings he often spent in the company of a courtesan.

If I had not been in the picturesque village of Mezzanelli just before I read Machiavelli's letter, I might like so many interpreters have considered his letter to Vettori as the reflection of a hopeless existence. However, while reading about his alleged misery it ocurred to me that Machiavelli actually describes an existence that in many ways is quite agreeable, maybe even more pleasant than Vettori´s strenuous luxury life in Rome. Machiavelli found himself far from Roman and Florentine violence and intrigues; the constant rat race within the corridors of power, stabbings in the back, betrayals and lies.

It seems that Machavelli became well acquainted with life in the village of his childhood, in any case his visits to Florence become increasingly rare and he complains that his “fine old gang" found itself in a state of disintegration. Tommaso del Bene had become stingy and required payment when he invited his friends over to dinner. Girolamo di Guanto turned out to be boring "like a clubbed fish" when his wife died, but had now become lovesick and incessantly babbled about a much younger lady he intended to marry. Count Orlando prattled about a young boy he was madly in love with. Donato del Corno had opened two stores which he constantly ran back and forth between, thinking only about making more money. No one wanted to talk about interesting topics like politics and culture, interaction had become dull and miserable. Though Ariosto has written a brilliant work, Orlando Furioso, but in this masterpiece he did not at all mention Machiavelli, instead he is refered to a bunch of bunglers.

In Sant'Andrea in Percussina, Machiavelli rose up early in the morning, carrying bird cages on his back to catch at least two, maximum six thrushes per day. He set his traps and then lied down in the thick grass by a rippling source in a shady part of his own forest, where he spent a couple of hours reading Dante and Petrarch, or the poetry of "the lesser poets," like Tibullus and Ovid, leaning back in the grass thinking about what they wrote:

I read about their amorous passions and about their loves, I remember my own and revel for a moment in this thought.

Reading this I envisage an arcadian landscape, with fresh greenery and clear water. To lie down in a forest of your own and remember joy and passion seems to be a very pleasant pastime. This at a time when neither cars nor airplanes could disturb the tranquility, or soil the fresh greenery surrounding you. In Machiavelli´s woodlands, there was plenty of game and birds. Italy was almost completely covered by forests, with the exception of small towns and villages surrounded by fields, vineyards and olive groves.

After resting and reading Machiavelli checked his bird traps and made it for the tavern:

I then move on up the road to the inn, I speak with those who pass, and I ask them for news of their area; I learn many things and note the different and diverse tastes and ways of thinking of men. Lunchtime comes, when my family and I eat that food which this poor farm and my meager patrimony permit.

After dinner, it often happened that Machiavelli went to one of his forests, which he gently had culled to build up a storage of firewood for the upcoming winter months. Whike in Mezzanelli I heard that it is still common for villagers to keep forests at their disposal, where they every year with discernment and good planning fell a certain number of trees, which wood they use for fuelling their large fireplaces during the harsh winter. Similarl,y Machiavelli cleaedr parts of his forests, retaining some of the wood for himself while selling the rest to friends and acquaintances in Florence. Almost every day he spent an hour or two in the woods:

in order check the work done the day before and to pass the time with the woodcutters, who always have some argument at hand among themselves or with their neighbors. And concerning this wood, I could tell you a thousand entertaining things that have happened to me …

When I read about the woodcutter the work I come to think of Giovanni Bellini's painting Saint Peter Martyr's Death that hangs in the National Gallery in London. It depicts how Sankt Peter, a Dominican inquisitor, and his companion are stabbed to death by two Chatar heretics. This happened in 1252, but Bellini lets the drama play out in his own time. In the background of the brutal murder scene, we discern some woodcutters who undisturbed continue cutting and collecting fuel. This makes me think of how Machiavelli lived a carefree country life while the Italy surrounding him seethed with violence, political intrigue and an ever increasing concern about an uncertain future. Bellini painted his painting only a few years before Machiavelli wrote his letter to Francesco Vettori.

After inspecting the progress of the work in the forest Machiavelli would once more take the road past the inn:

There I usually find the innkeeper, a butcher, a miller, and two bakers. With these men I waste my time playing cards all day and from these games a thousand disagreements and countless offensive words arise and most of the time our arguments are over a few cents; nevertheless we can be heard yelling from San Casciano.

San Casciano is two kilometers south of Sant'Andrea in Percussina and is the municipality's main town. When Machiavelli wrote to Vettori about his acquaintances in the village he stresses his own intellectual sovereignty and noble standing, which he assumes is separating him from them. He characterizes them as “vile people”, yes - he even abuses them by calling them "lice":

Caught this way among these lice I wipe the mold from my brain and release my feeling of being ill-treated by Fate; to be driven along this road by her, as I wait to see if she will be ashamed of doing so.

Nevertheless, I wonder if Machiavelli is entirely truthful in his contempt and while he passes his harsh judgments. It actually appears as if he thrived in the rustic village and through his interaction with its uncouth inhabitants. The tone he uses while writing about his rural friends could be some kind of role playing, to feign a superior attitude in front of the noble Francesco Vettori. The fact is that his time in Sant'Andrea in Percussina inspired Machiavelli to write his masterpiece The Prince, his Florentine History and the cynical comedy Mandragola, which became a huge success. His stay in Sant'Andrea turned his misfortune around. Through his writings Machiavelli became a widely recognized and respected author, princes began listening to him and offered him the lucrative assignments.

In Sant'Andrea in Percussina Machiavelli also fell madly in love with the sister of one of his friends. Throughout his married life Machiavelli had openly deceived his self-sacrificing wife, Marietta Corsini, who bore him four sons and two daughters, and he had all these extramarital escapades in spite of the fact that he called his family his most “loyal gang”. Machavelli´s personal correspondence is filled with references to mistresses and love affairs, though he mentions his wife only once, in a letter to one of his sons: “Simply tell her, that whatever she hears, she should be of good cheer, since I shall be there before any danger comes along.” While living with his family in Sant'Andrea in Percussina. Machi, as his friends called him, became captivated by Niccoló Tafani´s sister, who had been abandoned by her husband lived near the village:

Everything seems simple to me, and to her every whim I adapt myself, no matter how strange and contrary to my nature. And although I seem to have gotten into great difficulty, I feel, nevertheless, such sweetness in it – both because of what that sweet and rare face does to me and also because it has let me put aside the recollection of all my problems – that I do not want to free myself from it for anything in the world, even if I could.

Machiavelli was in spite of all his cynicism and narcissism a pleasurable companion. Just as easily as he exposed his contempt for other people, he could also prove himself to be a very loyal friend, honest and well organized. He enjoyed socializing with people from different social classes and was a tolerant person who often displayed his appreciation of each person's uniqueness, even though he often prefered to hid his preferences behind a facade of superior cynicism.

Machiavelli appreciated flexible people who nevertheless could stand by their own opinions, despite criticism and resistance. He called such resilience virtú, masculinity. In a leader virtú was expressed through an energetic fighting spirit, coupled with an ability to take well-founded decisions. By practicing virtú a leader could "accomplish great things" benefitting both himself and the State, and consequently - the people. For example, Machiavelli disliked Savoranola´s wrongheaded fundamentalism, but he admired his stubbornness, intellectual powers and his ability to convince others by setting a good example himself. Machiavelli also admired people who could express themselves clearly and in beautiful writing. One of his greatest pleasures, what made him feel most free and happy, was when he could sit down alone in his own room to read and write:

When evening comes, I return to my home and I go into my study; and on the threshold I take off my everyday clothes, which are covered with mud and mire, and put on regal and curial robes; and dressed in a more appropriate manner I enter into the ancient courts of ancient men. An am welcomed by them kindly, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born; and there I am not ashamed to speak to them, to ask tem for reasons for their actions; and they, in their humanity, answer me; and for four hours I feel no no boredom, I dismiss every affection, I no longer fear poverty nor do I tremble at the thought of death: I become completely part of them.

In all modesty, I would like to think that even I may be overpowered by similar feelings when I read Machiavelli's letter and remember what I have read and experienced before, not least remembering the time I spent with Rose and Esmeralda in Mezzanelli. An experience that facilitated my conversation with Machiavelli and made it possible for me to ask him why he acted as he did. Through great distance of several centuries, I came to assume that he actually was kind enough to talk to me.

Now, while writing my blog post, I may perhaps like Machiavelli say that I for four hours have felt no sorrows, avoided the idea of poverty, fear of death and have totally been absorbed by the company of an old cynic who died at my age, almost five hundred years ago.

Bondanella, Peter and Mark Musa (eds.) (1979) The Portable Machiavelli. New York: Viking Penguin Books. Viroli, Maurizio (2012) As If God Existed: Religion and Liberty in the History of Italy. Princeton, N. J.: Princeton University Press. Viroli, Maurizio (2004) Niccolòs smile: A Biography of Machiavelli. London: I.B.