EXPLAIN THE BIRDS TO ME

During my youth’s frequent cinema visits I used to smile at a commercial occasionally presented before the film began – a crane striding in a bog while the speaker voice stated: “Some people like to watch birds pecking in swamps.” Suddenly the bird explodes and disappears into a cloud of smoke with the comment: “But, we like cinema!”

Maybe it was like that, I liked cinema more than bird watching. The main reason was possibly that I did not have a proper pair of binoculars and did not pay any serious attention to the nature surrounding me, never far away since I lived in a small town. However, currently one of my biggest pleasures is to walk alone through the forest around our house by a lake in southern Sweden, listen to the birds and occasionally catch a glimpse of them. Nevertheless, my familiarity with these marvellous creatures mostly comes from books.

Ever since my childhood, I have been fond of bird books. My grandfather had three elegant leather leather bound volumes – Svenska fåglar efter naturen och på sten ritade I-III. Med text av professor Einar Lönnberg och 364 kolorerade planscher av bröderna von Wright, Swedish Birds Drawn after Nature and litographed I-III. With text by Professor Einar Lönnberg and with 364 Coloured Plates by the von Wright brothers. The books were originally published in 1838 and the magnificent illustrations were made by three Swedish-Finnish brothers. I do not know where Grandpa’s von Wright books ended up after his death and I must state I miss them quite a lot. I often sat curled up in one of Grandpa’s armchairs with one of the large volumes in my lap. It is difficult to explain the fascination I felt while looking at these wonderfully clear and strangely beautiful bird pictures. Perhaps it had something to do with a meticulous immersion in details and the wonder of birds.

As I flip through such exquisite bird books as the Wright brothers’ masterpiece, I come to think of the title of one of the Portuguese author António Lobo Antunes’ novels – Explicação dos Pássaros An Explanation of Birds. Many have tried to do just that, but it is an impossibility, as difficult as explaining what life is about, therefore I find the Swedish translation of the book title to be more adequate – Explain the Birds to Me. I assume what made Lobo Antunes choose such a title for a novel about a man's inability to accept what happened to him in his life, was the impossibility to explain the mystery of birds, those often beautiful, winged and well-sung creatures. The novel deals with the protagonist’s mother’s death in cancer, his alienation from his own family, how he shot away his first wife and their children, his shaky political stance and difficulties in understanding his new wife. The birds thus become an image of us all, their inexplicable existence as a symbol for our strange choices, subterfuges, and misbegotten ideas. Life as an impossible project.

Even as a child when I sat with Grandpa’s big bird book in my lap and through the large windows could look out across his flamboyant flower mountain and its backdrop of tall pine tress, in which magpies jumped around and screamed in a way that always makes me remember Tallebo, Home of the Pines, which Grandpa called his house and garden. I suspected that there was a mysterious relationship between me and the birds. A feeling that took hold of me when I from my friend Örjan received a facsimile edition Olof Rudbeck the Younger’s Swedish Birds as a gift for my sixty years birthday. Rudbeck's book, which he began to draw and write as early as 1693, is endowed with the same attention to details as the von Wright brothers’ masterpiece, which appeared 150 years later.

I have also enjoyed John Audobon’s (1785-1851) The Birds of America, which I in 1981 was acquainted with in the

library of the Instituto Cultural Domínicano Americano, where I often nested during my years in Santo Domingo.

For hours I could sit in the Institute’s library immersed in admiration of Audobon’s depictions of birds, which harmonized the animals with their surroundings; the flowers, the trees, the water and often also dramatizing their existence within carefully portrayed environments.

That I found Audobon in the Dominican Republic was an interesting coincidence, since he was born in the neighbouring Republic of Haiti, during a time when it was a French colony called Saint-Domingue. Audobon’s father owned a slave-run sugar cane plantation. Already as a six-year-old child Audobon was forced to move to France, together with his father and siblings. The ruthlessly exploited and tormented plantation slaves, with whom John’s father, like so many of his slave-owning friends, had a multitude of children, had revolted and no white man could any longer feel safe in the rebellious Saint-Domingue. An eighteen-years-old Audobon then left France for the United States.

Considering our contemporary condemnation of the artistry of nasty people I would actually not be able to enjoy Audobon’s mastery, as little as it is now permissible to admire films by the paedophile Roman Polanski. Unfortunately, I cannot help surrendering to Audobon’s exquisite art (and also appreciate Polanski’s films), even though he was obviously a rather unpleasant person.

Audobon was certainly a genius, whose contribution to ornithology and art is invaluable, though he was endowed with a complex character and was repeatedly committed to a contemptuous behaviour, which even by the lax standards of the time was quite indefensible. He was accused of lying, academic fraud and plagiarism. He enslaved black people and wrote critically about emancipation. Audobon stole human remains and sent skulls to a colleague, who used them to, through his “scientific research”, prove that white-hued persons are superior to “non-whites”.

In the United States, Audubon spent more than a decade as a businessman in Kentucky, where he owned a thrift store in the city of Henderson and also was engaged in the slave trade. For some time, Audobon was relatively successful, but in 1819 he was imprisoned accused of bankruptcy and fraud. Released, Audobon travelled through the wilderness of the United States, hunting and depicting its bird fauna. Well aware of the English’s romantic craze for nature depictions, he sailed to England in 1826, bringing with him an impressive portfolio of life-size bird depictions and his fortune was made. Audubon became a wealthy and admired man.

It was in Santo Domingo I became familiar with Audobon’s life, coming across an odd character named John Chancellor, who was also afflicted by a fair dose of racism. Chancellor bought and sold antiquarian books about Haiti and the Dominican Republic and gave me two biographies he had written; one about Wagner and one about Audobon. Unfortunately, both monographs were based on inadequate research and I later found quite a lot of inaccuracies in them. Nevertheless, I appreciated that Chancellor gave me the books and they became the gateway to better and more detailed reading about these two, undeniably unpleasant and prejudiced geniuses.

Back to the birds. During a long life I have become acquainted with several bird watchers. In the Swedish town of Lund, for example, I had a neighbour who worked as “developer” at Tetra Pak, a Swedish-Swiss multinational food packaging and processing company, though his immersive interest was to wander around the Scanian plains, or in lush forest groves, to record bird sounds. He had a large number of tapes and from time to time he played them for me to demonstrate how birdsong differed from area to area, almost like human dialects. I had a hard time distinguishing the tiny nuances, but nevertheless found it fascinating that someone to such an extent could be engaged in a scrupulous analysis of birdsong.

A few years later I read Edward Grey’s The Charm of Birds, since Lord Grey in his book demonstrated an unusually large and lively interest in birdsong, the Swedish book title had the somewhat more adequate title Birds and Birdsong. Lord Edward Grey, First Viscount and Third Baronet Grey of Fallodon, was between 1905 and 1916 British Foreign Secretary. Despite an obvious lack of knowledge of foreign languages and a distaste for diplomacy he was nevertheless a committed and skilled negotiator, who unfortunately became entangled in the run-up to World War I.

It was Lord Grey who at the outbreak of that war made the classic statement: “The lights go out all over Europe; we will not see them lit again during our lifetime.”

When the war ended, Lord Grey stated that his prediction had been correct in the sense that the consequences of the war had damaged an entire European generation and these wounds would surely be reopened once again. However, he had by then retreated to his favourite pastime – fly fishing in the crystal-clear, water cress covered Itchen, which flowed through his property in Hampshire, while he listened to the birdsong in the dense greenery by the riverbanks. What fascinated me when I read Lord Grey's well-written book was his ability to stimulate an attentive interest in birdsong.

He captured the feelings that spring grants me in the forests around our Swedish home – the half-hour before sunrise when “like morning stars all the birds sing together”, which Lord Gray described as jubilant euphony. In this choir he distinguished the beautiful voice of the wood warbler. A slender, small bird which discrete colours harmonize with newly sprouted beech leaves:

The soft green and yellow colours of the bird are in tone with the foliage, and its ways and movements and general happiness animate the beauty of young beech leaves: wonderful and perfect beyond description as this beauty is, the presence of a wood-warbler can still add to it.

According to Lord Gray, the wood-warbler has two tunes in his repertoire. Clear and joyful tones that tremble in short intervals and are repeated again and again. They are inter-weaved with a clear and very beautiful song, repeated ten times in slow succession.

Lord Grey assumes that the impression a human listener obtains from these melancholic tones is that they express a deep sadness. The tone is pathetic, there are tears in the wood warblers song.

In May, the birdsong in Lord Grey’s lush forestlands was taking on a new meaning. For overwintered birds the arrival of spring means a reawakening of life, while the songs of migratory birds announce their arrival. Each and every bird is through his song assuring that he is reanimated, or has returned home, is choosing his territory, searching for a mate and a place to build his nest.

The singing at dawn becomes a “tapestry translated into sound.” It starts with a few muted notes of thrush song, waking up the tits and soon “sawing notes, bell notes, teasing notes” fill the air, the song of mistle-thrush, merle and mavis, maybe also the rounded notes of an owl, and above it all rises the voice of the blackbird; warm and clear “light as amber among the sharper flood of song.” A vocal attire constituted of innumerable stitches of sound.

Lord Grey nurtured a special love for the wren. According to him, its song is not the best, though its “a good song , clear, distinct, musical and pleasant; it is elaborate rather than simple and is well turned out.” The impression of the wren’s song is enhanced by its distinctive appearance and specific character. Even though it is a bird of insignificant size, it has resolutely protruding tail feathers and a violent temper. Lord Grey watches the arrogant little bird during its spring mating season and gets the impression that the song of the wren contains more of challenge and triumph, than love. He surprises two male wrens, which on his lawn are involved in such a violent battle that they ignore his threatening presence. When one of them finally emerges victorious from the fight and the defeated bird has retreated, the victor flies to a nearby bush and from where he fills the air with a triumphant song.

In the birds’ dawn choir, Lord Grey distinguishes the blackcap’s voice, so perfect and moving that he considers it to be among the foremost English songbirds. The blackcap’s singing is loud:

exceedingly sweet, but also spirited: it is not very long, but is frequently repeated: there is a great variety, but the thing done is absolutely perfect. There is not a note that fails to please or to be a success.

The garden warbler’s song is also beautiful, but it seems as if that bird can never completely clear its throat and let out sounds as pure and free as those as the blackcap. However, in one respect the garden warbler is superior to its rival – his by all means beautiful song is more enduring, it lasts longer.

Lord Grey asks his readers to listen attentively to the birds triumphant dawn choir and above all notice how the blackbird’s euphony add life and soul to the entire symphony. According to Lord Grey it is impossible to explain why the blackbird’s singing surpasses any other bird’s. Why it means so much to us humans. He suggests that it might be due to a sense of “familiarity” conveyed by the blackbird’s song. The tunes of other birds are for sure quite pleasing, though the song of the blackbird directs itself to the soul of its listener. It touches deep-seated emotional strings, which ultimately unite us with the pitch-black bird. But alas,the euphoria is limited. The blackbird gives us barely four months of bel canto. He begins singing regularly by mid-March and before the end of June he falls silent. In July we might listen to the last spring tones coming from mavis and robin, but the farewell to these birds is not as melancholy as listening to the tones of the last blackbird, knowing that a long time will pass until we hear them again.

During autumn we listen to the owls’ desolate screams and hooting, sounding as if they were harbingers of something threatening and mysterious. Almost as sonorous as the solitary, enigmatic sound of the bittern. The owl’s scream consists of a long, calm and fine tone, which pauses for four seconds, to be followed by a drawn-out tone, which at first vibrates and then culminates at a soothing, full volume. The owl’s cry gives life to the forest and it would be unsettlingly quite if it ceased.

When I read Lord Grey’s careful descriptions of how nature and the behaviour of its inhabitants, the birds, is changing in accordance with nature’s course, I am reminded of the forests’ powerful breathing which I perceive during solitary forest walks, or while rowing across our lake in Swedish Göinge.

Deep down in my mind, I am upset about all kind of killing – war, slaughter, hunting, even fishing, though I nevertheless enjoy talking to fishermen and hunters and have often heard them describe how their waiting for prey unites them with their immediate surroundings. How sitting still and quite during the long waiting of their hunting sessions makes them realize how much that generally is hidden from sight and hearing. How our threatening presence in forests and groves arouses fear and suspicion among the animals, making them hide and become silent.

While we thoughtlessly walk through forests we see very little of all the life within them. Maybe we catch a glimpse of a few small birds, surprises a deer or a hare, though they quickly escape and hide among bushes and burrows. Upon our arrival alarm signals are, unknown to us, sent out and animals quickly disappear from our sight. However, we are constantly observed by the wild life, which might be in constant fear, anticipation and even excitement.

If, on the other hand, we sit down and silently scrutinize the surrounding nature we will soon discover how shy and easily frightened animals forget about our presence and resume those activities we previously have disturbed them in. Squirrels and rabbits appear, birds sing and thrushes rustle in the dry leaves around us , soon we might see how a moose or a small flock of deer appear.

What I find endearing in in people able to describe painters, and then perhaps mainly in birdwatchers, is how they patiently pay attention to “the little life”. The great patience of ornithologists, a quiet and silent wonder at the life around them, a respect for nature that makes them incapable of harming the creatures living there. It is enough for them to look at the rich life that surrounds them. Yes – several of these nature observers are obviously able to transform their activities into a part of their own life.

That’s probably why I find pleasure in reading and flipping through nature writers/artists’ books. For example, the Swedish writer and artist Gunnar Brusewitz, who among his many works of art designed the diplomas for the Nobel Prize in Literature, but his most famous works are a large amount of illustrated books, dealing with nature and animals.

I am particularly fond of his Diary from a Lake and Waterside Reflections, in which he based upon sceneries from his artist’s cottage by the lake-shore of Sparren, in the Swedich landscape of Roslagen, follows the changes of seasons and the passage of the years. With a view towards the four quarters he portrayed with skill and empathy the flight and presence of birds and the four-legged animals which walked past his haunt. Through Brusewitz’s books I perceive the scent and sound of the forest, the warmth or coolness of the air.

More minimalist nature studies were done by another artist, Björn von Rosen, who in his Conversation with a Nuthatch described his “platonic friendship” with a small bird, which I, by the way, after giving a lecture about it when I was in the fourth grade always have felt an affinity with.

Björn’s and the nuthatch’s relationship began when the blue shimmering little bird approached the artist’s windowsill while he for several months was bedridden in a troublesome illness. Björn’s wife got the idea to open the window towards the winter landscape outside, fill empty matchboxes with cookie crumbs, hemp seeds and pieces of cheese, placing them on the windowsill so Björn from his sickbed could enjoy watching how birds came to visit and devour the procurement.

A particularly prominent guest was a constantly recurring nuthatch. One morning when Björn von Rosen opened the window and held out his hand with some cookie crumbs in the palm, the nuthatch placed itself on his fingers and began to nibble the crumbs. With a shudder of pleasure the convalescent experienced how “the feeling of her small dry claws lingered on the skin of my fingertips while I returned to my sickbed.” This episode became the prelude to a daily routine which consisted of Björn getting up from the bed, opening the window, stretching out his hand and immediately becoming visited by the nuthatch, eating crumbs from the palm of his hand.

When Björn had recuperated and together with his two bassets resumed his daily walks, the nuthatch followed him, jumping from branch to branch. Eventually the bird demanded only cookie crumbs. If it turned out that Björn only had bread crumbs in his hand, she contemptuously threw them away with a jerk. Eventually, the nuthatch’s mate also appeared. He was interested in nut crumbs, but at first he did not dare to grab any from Björn’s outstretched hand, though he soon became as fearless as his wife.

Björn’s friendship with the two nuthatches and their children continued for nine years and in his book he described small episodes and reflections concerning the lives of these small birds, and what he assumed to be their way of thinking.

When I read books like those written and drawn by Brusewitz and von Rosen it happens that I envy avid bird watchers, for example my friend Magnus who had a house built for himself and his family in the southernmost Swedish beach town of Falsterbo, with an upper room filled with bird books next to a terrace from which he with his binoculars can watch the rich bird life. Forester as he is in service of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Magnus has had ample opportunities to get acquainted with the bird life in different parts of the world, while I remain an incorrigible and ignorant amateur, who watch birds in books and through my computer.

It was not impressions from any small birds that made me write this blog post, but a recent visit I and Rose made to Abu Dhabi. Together with our friend Lupita, who had been living in the country for a few years, we paid a visit to the Zayed Heritage Center, a museum dedicated to Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan (1918-2004) Father of the Fatherland, who in Abu Dhabi is venerated with a devotion of saintly proportions. He was the main driving force behind the formation of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which in 1971 united seven emirates along the coast of the Persian Gulf. He became the Union’s first Ra'īs, President, a position that Sheikh Zayed kept for 33 years, from the founding of the UAE until his death in 2004.

In 1966, Sheikh Zayed deposed his brother Sheikh Shakhbut and thus became the undisputed ruler of Abu Dhabi. He had previously realized the importance of obtaining the full support of the people in exchange for improvements in their standard of living – jobs, fixed income, social safety nets, general health care, free and obligatory education for all. After the British withdrawal in 1967 (they had controlled the impoverished emirate since the early 19th century), Sheikh Zayed opened his country to a massive immigration of skilled workers, along with a clause in the constitution stipulating that an immigrant could apply for citizenship only after proving that he/she spoke fluent Arabic and had lived in the country for at least 30 years. However, Sheikh Zayed also stated that “guest workers”, apart from the right to vote and becoming involved in politics, would have the same rights and obligations as citizens of the Emirate.

Compulsory schooling for boys and girls was introduced, universities were founded, religious freedom was established, although state censorship of all media was maintained. Roads were built and public access to drinking water and health care was secured. In particular, Sheikh Zayed renegotiated the oil concession agreements, ensuring that Abu Dhabi obtained the lion share of revenues from all oil- and gas production, thus putting an end to the British monopoly on oil extraction, paving the way to the United Emirate’s enormous wealth. The UAE currently has an annual GDP of about 400 billion USD, a third of which comes from oil revenues, of which Abu Dhabi controls 94 percent.

When Sheikh Zayed in the mid-1960s gained total power over the country, Abu Dhabi had no paved roads, no hospitals, no schools (except for a few boys and men who attended a Qur'anic school, 98 percent of the population was illiterate). It was an even worse backwater than before since cultured pearls had put a stop to revenues from pearl fishing, which previously had been virtually the only source of the Emirate’s export revenue. Abu Dhabi’s capital consisted of a stone building that sometimes housed representatives of the British government and some huts gathered around Qasr Al Hosn, the Nahyan family’s Fortress/Palace.

I thought about this as I stood by the panoramic windows of Lupita’s and Dino’s apartment on the fifty-second floor of one of the impressive Ethiad Towers, enjoying a view of the azure-blue waters of the Persian Gulf. In a distant haze I discerned Qasr al Watan, the newly built Emirate Palace and site of the UAE Government, actually one of the most beautiful buildings I have ever visited. It was hard to believe that in just fifty years, this lavish, well-organized, extremely clean, and secure nation had risen from the sands of a dirt-poor Bedouin kingdom. After all, it was no wonder that the nation revered the unparalleled Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan.

We were the only visitors to the Zayed Museum. Its manager, a friendly, elderly man who had known the Emir personally, offered us tea and gave me a magnificent book about the archaeology of the Emirate. The museum was filled with all imaginable curiosities left from the Sheikh’s legacy. What fascinated me most was the amount of pictures and objects which bore witness to Sheikh Zayed’s immersive interest in falconry.

The main reason for my interest in this activity was that I had previously visited several of Frederick II's (1194-1250) castles and forts in southern Italy and thus had come to read something about his great passion for falconry. Another reason for my sporadic falconry interest emerged from the fact that when I more than ten years ago was working at the UNESCOs Department of Intangible Cultural Heritage a colleague of mine told me she was, among other things, working on an application for including falconry in the Organization’s Representative List of Humanity's Intangible

Cultural Heritage, an effort that finally became completely realised a year ago. She had asked me to write something about the gender aspects of the application and I then found that women had been intensely engaged in falconry, especially in the Far East and Central Asia, though it had also been a popular pastime among aristocratic ladies during the European Middle Ages.

We find, for example, falcon-hunting women in the so-called Tymouth Hours, an “Anglo-Norman” prayer book from the 1330s, in which each page is illustrated with everyday scenes, which generally has nothing at all to do with the text.

At UNESCO, I read a medieval poem by a writer who was active in Sicily by the end of the 13th century, now known as Nina the Sicilian, Nina from Messina, or Dante’s Nina. Her sonnets are recorded in a manuscript in the Vatican Library (Codex 3793) in which someone by the end of the 13th century copied 137 ”songs” and 670 sonnets. Several of these belong to the so-called Sicilian School of Poetry written in Italian and preceding the somewhat later Tuscan School, with giants like Petrarca and Dante.

Nina’s sonnets are included in the part of codex 3793 which their copyist described as written by ”unknown” authors (the free andclumsy translation below is mine):

Tapina me che amava uno sparviero, Alas, I who once loved a falcon,

Amaval tanto ch’io me ne moria so much I could have died from love.

A lo richiamo ben m’era maniero, When I called him, he was obedient.

Ed unque troppo pascer nol dovria I fed him, not too much but enough.

Or è montato e salito sì altero; Now he has fled and reached

Assai più altero che far non solia; heights I do not know,

Ed è assiso dentro a un verziero, there he sits in a birdhouse,

E un’altra donna l’averà in balìa. for by another woman.

Isparvier mio, ch’io t’avea nodrito; Oh, my falcon, which I raised.

Sonaglio d’oro ti facea portare, I gave you golden bells to carry,

Perchè nell’uccellar fossi più ardito so no bird would harm you.

Or sei salito siccome lo mare, You rebelled, like a stormy sea.

Ed hai rotto li geti e sei fuggito, You destroyed your ropes, tore yourself free,

Quando eri fermo nel tuo uccellaro. as soon as I had taught you how to hunt.

As with several other troubadour singers, and even contemporary Persian Sufi poets like Jalal al-din Rumi, Nina’s poetry is ambiguous in the sense that it describes earthly love against a religious backdrop. The poem’s ”other woman” could just as easily have been the Virgin Mary who received the deceased lover/falcon in her Paradise, as an earthly woman with whom the lover/falcon had forsaken the poetess.

Early records indicate that Nina was a young lady favoured by Frederick II’s mother, Costanza d’Altavilla, daughter of Sicily’s Norman ruler Ruggero II and married to his successor, the ruthless German-Roman emperor Henry IV of Hohenstaufen.

Costanza d’Altavilla died when Frederick was only five years old, though he grew up in the refined court environment created around his mother. Frederick was a rather skilled sonnet poet, who in his poetry praised the courtly love of his time. Although he wrote extensively on falconry, none among Frederick’s surviving poems does, like other Sicilian poets, mention falcons and falconry as symbols of love between man and woman. Falconry was in several Medieval, aristocratic circles considered to be the most perfect occupation of court life. For many men and women, it was an almost immersive passion, often sublimated in erotic depictions and verse.

This is evident, for example, in several illustrations of Codex Manesse, a Liederhandschrift (a manuscript of songs) compiled in 1304 for the wealthy Manesse family in Zurich. The manuscript contains works by 135 Minnesänger, German troubadours, each of whom is presented with one or more poems, exquisitely illustrated with 137 hand-painted miniatures.

The refinement and connection of falkener culture with eroticism is prominent in one of Decamarone’s short stories. This collection of tales, which in 1353 was published by Bocaccio in Florence, is not unique in the sense that a collection of more or less well-known fairy tales and legends is presented as if they had been told in a small, refined, aristocratic society, was a fairly standardised literary ploy. Decamarone’s fame is mainly linked to the elegance and stylish ease with which Bocaccaio tells his stories. This is evident in the introduction to the ninth story on the fifth day a spiritual company of aristocratic gentlemen and ladies are telling each other, after isolating themselves from the plague in Florence in a rural manor:

You are to know, then, that Coppo di Borghese Domenichi, who once used to live in our city and possibly still lives there, one of the most highly respected men of our century, a person worthy of eternal fame, who achieved his position of pre-eminence by dint of his character and abilities rather than by his noble lineage, frequently took pleasure during his reclining years in discussing incidents from the past with his neighbours and other folk. In this pastime he excelled all others, for he was more coherent, possessed a superior memory, and spoke with greater eloquence.

The story that Bocaccio puts in Borghese Domenichi’s mouth tells about the young, handsome and wealthy Federigo, who is engrossed by an all-consuming love for the “most beautiful and pleasant” lady in Florence; the chaste, high-minded Lady Giovanna, who unfortunately married to another man. For the sake of his love and to win Giovanna’s attention, Federigo wastes his wealth on exquisite spectacles, tournaments, Catholic masses and sumptuous dinners. However, Lady Giovanna, remains faithful to her husband and only devotes a distracted interest to Federigo and his activities. As a result, Federigo ruins himself and ends up living frugally in a small country house where he tries to turn his passion for Lady Giovanna into an immersive interest in falconry. The only wealth he has retained is a beautiful, perfectly trained gyrfalcon, which is admired by his entire neighbourhood.

When Lady Giovanna’s husband dies, she retreats to her deceased husband’s country estate, bordering Federigo’s plot of land. Her son is captivated by the neighbour’s falcon and follows him during his daily hunts. However, the youngster becomes seriously ill. When a despairing Lady Giovanna perceives how her son fades away day by day she asks what he possibly might assume would cure him from his distress. After several days of hesitation, he reveals that a wonderful gift might get him on the road to recovery. When Lady Giovanna urges her beloved son to mention such a gift, he answers “Federigo’s gyrfalcon”. Lady Giovanna, well aware of Federigo’s longing for her love, leaves for the forsaken lover’s cottage with the intention of persuading him to give her his falcon.

When Lady Giovanna arrives, in company with her refined ladies-in-waiting, the confused and overwhelmed Federigo tries imagine what sumptuous meal might through her stomach reach the coveted woman’s brain and win him Lady Giovanna’s loving attention. He spends his last pennies on a delicious dinner, but at first he does not have enough imagination to be able to figure out what he should present as an irresistible main course. It must be something wonderful, something almost beyond human imagination. He comes up with the thought that only a dish which in itself signifies, or even includes his great love and passion for Lady Giovanna might through her delight turn her tender passion towards him. His gaze falls on his pampered and well-fed falcon. Federigo twists the bird’s neck and lets his temporarily hired master chef prepare it.

And, miracle of miracles – the sumptuous meal makes Lady Giovanna mild-tempered and she looks gratefully, almost lovingly, at the deeply moved Federigo. Finally, she dares to tell her host that her son is dying, but that she imagines that he would recover if Federigo gave him his gyrfalcon as a gift. The desperate Federigo is forced to admit that they have just eaten the bird. Lady Giovanna becomes appalled when she realizes that all her hope for her son’s recovery is gone and he actually dies after a few days. Nevertheless, deep down in the depths of her heart, Lady Giovanna is greatly moved by Federigo’s desperate attempt to win her love and his sacrifice of the beloved gyrfalcon has indeed finally awakened her love for him. She marries Federigo who now becomes a wealthy man and when he has reached the goal of his fervent desire he also turns into an enterprising and frugal husband.

For centuries, even millennia, falconry has been both an immersive occupation and a source of prestige within sophisticated court circles around the world, possibly with the exception of ancient American civilizations, like those of the Mayas and Incas.

In China, there are a number of historical testimonies, in the form of literature, poems, paintings and porcelain. proving falconry’s great popularity within court culture.

Chinese falconry was inseparable from politics and power. Written documents dating back to 700 BCE bears witness to the importance of falconry. Especially during the Tang Era (618-907 CE), Falkener culture flourished and was highly esteemed among the Empire’s potentates – emperors mandarins and warlords. Here as well, there was a connection between eroticism and falcons, as in Chang Hsiao-p’iao’s poem from 826 CE:

The Lay of the Hungry Hawk

She imagines the plain afar

where the hares are plump just now:

She turns her horned bill a thousand times

and shakes her feather coat:

Just let her peck loose

this knot in her silken cord …!

But unless she got the call of man

she would not dare to fly.

The poem clearly alludes to women’s longing for freedom, which is, however, limited by the control their husbands has over their lives.

For centuries, Falkener culture continued to flourish at Chinese courts. Below are some falcon portraits of the versatile Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766). He came from a wealthy Milanese family and when he joined the Jesuit order, Castiglione was already a skilled artist. At the age of twenty-eight, he was introduced to the Imperial Court in Beijing, where his art was much appreciated. Castiglione had soon learned Mandarin and adapted his Western painting technique to Chinese taste. Castiglione's hybrid art came to form school, especially through his magnificent animal representations

Falconry arrived from China to Korea around 200 CE and from there the tradition was passed on to Japan.

The first Japanese written evidence for falconry dates from the 6th century CE and soon a unique and sophisticated court culture had developed around falcons and hawks – Takagari. A tradition especially linked to the Shinto religion and often expressed in the hunting societies’ beautiful costumes and aesthetically pleasing paraphernalia. A specific, ritual falconry was cultivated within various “schools” such as Suwa-ryu and Yoshid-ryu, which cherished a solid knowledge of everything concerning birds of prey, both domesticated and wild, and , for both men and women a profound familiarity with falconry became a status symbol .

In India, falconry had been practised in aristocratic circles as early as 600 BCE, but it was not until the reign of the Mughals (1526-1858) that the sport developed into a passion among wealthy men and women.

Falcons and other birds of prey were not only symbols of a desire for freedom and eroticism, but also of ruthlessness and war. The screaming of falcons and hawks as they flew in front of attacking armies was a call for bloodshed and a search for glory on the battlefields. Already 220 BCE, the poet Sung Yü stated that autumn is a

season of desolation and blight,

the avenging angel,

riding upon an atmosphere of death.

However, a thousand years later, the warrior poet Lu Yu glorified autumn as a heroic time of falconry and commemoration of ancient Chinese victories over Tatar invaders:

Swift falcons leave the gauntlet with sturdy talons and beaks

and bold men fondle their swords with frenzied spirits.

There are many indications that falconry originated in Central Asia, among peoples called Huns, Mongols or Tatars. Among these peoples, falconry was practised more than 3,000 years ago and birds of prey are of great importance in Central Asian and Siberian shamanism.

Shamans are believed to be able to change their demeanour and use paraphernalia and costumes mimicking birds of prey and in trance widely around the world, even to realms unknown to us living people.

Among Mongolian khans, falconry achieved a high level of refinement and creativity. Mongolian falconers use several different species of birds of prey, including large and complicatedly trained birds, such as eagles. During their extensive military campaigns, Mongol armies used such to hunt for provisions and as a relaxation between battles. At the time of Marco Polo’s to Kublai Kahn’s court (1275-1292) there were 60 officials who only dealt with the management of the emperor’s hunting falcons, as well as 5,000 hunters and 10,000 fully employed falconers.

Being fierce conquerors many Mongols did probably not regard the peregrine falcons as images of freedom and love, but as bloodthirsty predators who fought in their service.

In the 1998 Disney film Mulan, the murderous leader of the invading Hun Army, Shan Yu, has a ruthless Tatar falcon, Shan-Yu, as his only trusted and perhaps even respected “friend”.

The obvious, almost passionate love that avid falconers show their falcons seems to reflect a great admiration for birds of prey’s ability to adapt to the nature surrounding them. These birdmen seem to nurtures a desire to see and experience the world through a falcon’s eyes and instinct. Among some of them, there may also be an exciting feeling of being able to engage, in an almost identical fashion, participate in the falcon’s hunt for prey, a fervent desire to gain some of its instinctive strength and ruthlessness, which has nevertheless been subjected to their human owners through training.

The author Terence Hanbury White (1906 - 1964) author of The Once and Future King, a skilfully retold King Arthur saga, was born in Bombay and had an unhappy childhood. His alcoholic and moody father was District Superintendent of Police, while his mother was an emotionally chilled lady. The couple soon divorced and the young White was sent to an English boarding school where his emotional misery continued unabated.

As an adult, White fought against his homosexuality and other sexual tendencies. He wrote:

All I can do is behave like a gentleman. It has been my hideous fate to be born with an infinite capacity for love and joy with no hope of using them.

An acquaintance stated that T.H. White: “did not fear God but was fundamentally afraid of humanity”. In 1946, White settled on the canal island of Alderney and became increasingly alcoholic over time. It was at Alderney that he wrote the book The Goshawk, which is about how the young White after reading the lines in an old book about falconry “and the bird returned to its wild state”, became obsessed with the idea that maybe he too could be transformed to "a free savage". He got a pigeon hawk from Germany. The bird was “cruel and free”. White came to the conclusion that the only way to tame the hawk would be to deprive it of sleep, which resulted in White also came to suffer from insomnia. According to him, man and bird ended up in a common state of delirium, attraction and repulsion. It could be likened to a love affair. White never managed to tame his hawk, nevertheless he found that there was a connection between humans and animals that could be both liberating and painful.

An immersive passion for falcons, and especially valuable gyrfalcons, seems to be particularly alive in Abu Dhabi, something that not only the Sheikh Zayed Museum bore witness to, but also the emirate's eminent falcon hospital.

A place where sick and injured falcons receive excellent care in operating theatres and individual air-conditioned rooms, with place for more than the 200 falcons, which are cared for there, in addition to the 11,000 birds of prey visiting the hospital each year. The hospital’s German manager, Margit Müller, explains:

Falcons are fascinating, each has its own special, independent character, the way they express themselves is completely unique, almost magical. In Arab culture, they are not considered pets, but are rather considered to be family members who should be raised and cared for as such. They live with the family, have their own seat in the living room and many even sleep in their owners’ bedrooms.

The Falcon Hospital also evaluates falcons and hawks on the basis of their strength and health. The judgement of medical falcon authorities is of great importance in a country where falcons are an exclusive status symbol. Gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) are the largest falcon species and their natural habitat is mountains and tundra. The Icelandic gyrfalcon is considered to be especially valuable. The large island occasionally went by the name Falcon Island and the white gyrfalcon can be seen on the top left of the Icelandic Republic’s coat of arms.

The white gyrfalcon is the most expensive falcon variant. A thoroughbred gyrfalcon can be worth more than 150,000 USD. In November 2021, the young gyrfalcon Shaheen was in Libya sold for 450,000 USD.

Valuable falcons are tenderly cared for by their wealthy owners and several of them even take their falcons on air travels, especially when it comes to introducing them to a particular game. Above all, a kind of desert birds called Houbara Bustard (Chlamydotis undulata). Theses are nomadic birds moving around arid areas in North Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, being rare in most parts they are especially numerous in Afghanistan.

The presence of houbaras in that country was leading to a near catastrophe for the Emirates’ wealthy sheikhs, several of whom, especially Abu Dhabi’s Sheikh Kalifa bin Zayid and Dubai’s Sheik Makhtoum, who along with other gyrfalcon aficionados each year are travelling travel to the houbara hunting ground in southern Afghanistan. border areas to Pakistan. Bin Laden used to haunt this particular areas and since he had grown up in Saudi Arabia’s Bedouin tradition and he was also a falcon aficionado.

In late February and early March, houbaras gather in hard-to-reach, arid areas south of Kandahār. During the hunting season, and perhaps they still do, wealthy sheikhs of the Arabian Peninsula flew with their falcons into Afghanistan’s relatively houbara-dense areas and set up luxurious tent camps there. In February 1999, the CIA’s Bin Laden Tracking Team announced that satellite images had convinced them that their most-wanted terrorist was moving around the falconers’ tent villages and was possibly even hunting together with the sheikhs. Gary Schroen, CIA’s site manager in Riyadh and leader of CIA’s Near East Division, recommended that the entire tent city should be bombed:

Let's just blow everything up. And if we kill bin Laden, and five sheikhs in the strike, I'm sorry. But, what do they have to do with bin Laden? He’s a terrorist. If you lie down with the dog, you wake up with fleas.

It was extremely close that the UAE Sheikhs became victims of their falconry passion. However, at the last minute Richard Clarke, National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection and Combating Terrorism, advised against the attack. Clarke was closely acquainted with the UAE’s powerful emirate families, especially the Abu Dhabi Nahayan clan, and he was well aware that the UAE’s ports, oil and gas were essential to U.S. warfare. Clarke could thus easily overlook the fact that falconry blinded its practitioners to such a degree that they did not care if skilled participants in their hunting teams were terrorists. It was hunting and not politics that mattered, at least during the limited time when houbaras gathered in Kandahār's desert regions.

All those who had lived with Arabs upholding ancient Bedouin traditions knew how important Falcons could to them, especially among wealthy and powerful men. Abdelrahman Munif, a Jordanian-born Saudi who worked in the Middle East oil industry, wrote a fascinating five-part story about how oil had changed life on the Arabian Peninsula, corrupting its leaders through luxury and abundance. It is an extensive work in which each volume contains more than six hundred pages. Only the first two parts of Munif’s Cities of Salt have been translated into English.

It’s a fascinating read. The story progresses at a calm, patient pace, almost providing the reader with a feeling that he/she is travelling through the desert on a patient, arduous camel. Munif’s stories are filled with a peculiar symbolism. They have no heroes, thougfh thousands of characters and names pass by, creating a dense web of voices and legends, this while modernity relentlessly changes and transforms everything. Munif declares that ancient traditions have been falsified to such an extent that they now can be used as a defence of totalitarianism, corruption and subtle oppression. His novels are banned in Saudi Arabia, but available in the UAE.

An episode in the first novel tells about how an emir arrives at the fictional port city of Harran. He is disapproved of by the city’s Arab population, while the oil-exploring Americans and cunning, local businessmen swarm around him. The emir claimed that he had come to the city to do justice and implement law and order, though it soon became apparent that he primarily wanted to enrich himself by conspiring with the Americans and he only distractedly listened to wishes and demands coming from the urban population.

Dabbasi, the city's most crafty merchant, gained a reputation for being a devil since he knew how to manipulate the Emir:

because from the minute he started talking about hunting, the emir underwent a total transformation—when he listened to Dabbasi’s stories, he became like a small child and asked him to sit down by his side.

Dabbasi had observed how several of the emir’s men kept pet falcons on their wrists and lovingly caressed and talked to them while the emir sat uninterested judging the people of Harran. Dabassi had then in a loud voice suddenly declared that the areas around Harran were well known for their houbaras, which appeared during the winter months. The emir’s face lit up and he became extremely attentive to everything Dabassi said about falconry. When Dabbasi had captured the emir’s interest, he was able to convince him that it was good politics to listen to the locals before he negotiated with the Americans. “Truth is truth and the natives are closer to us than the strangers” stated the emir before he once again turned to Dabassi and with him immersed himself in conversations about houbaras and gyrfalcons. When the emir finally took farewell, it was from a benevolent urban population and when he had mounted his camel he turned to Dabbasi with the words: “When winter comes and it is as harshest, then I will come back and we ride in search of all the hunting grounds you mentioned. ”

Sir Wilfred Patrick Thesiger (1910-2003) was born in Addis Ababa as the son of the British Consul General. At the age of eighteen, he was sent to England and educated at Eton and Oxford, where he mainly studied history. In 1930, he was invited to Ethiopia by his father’s friend Haile Selaisse. On the Ethiopian Emperor’s behalf, Thesiger made several research expeditions. During World War II, Thesiger commanded Ethiopian forces fighting the Italians, as well as Druze military units fighting the Vichy regime in Syria. After the war, Thesiger was active in the fight against migratory grasshoppers on the Arabian Peninsula and lived with the Bedouins he followed on their migrations through the vast desert area of Rub al-Khali – the Empty Quarter.

In his book Arabian Sands from 1959, Thesiger describes a timeless area with people who lived the way they had done for thousands of years. He participates in raids against hostile Bedouins, is hunted and captured by bandits, his travelling companions are threatened with blood revenge, slave hunters are in pursuit of lonely wanderers. Thesiger encounters hospitable sheikhs, revered by their subordinates while they surround themselves with harems, slaves, valuable camels and gyrfalcons.

Thesiger wrote that he his craving for adventure had been established during his Ethiopian youth. In his old age he wrote how overwhelmed he once had been while watching tribal warriors returning from battle:

I had been reading Tales from the Iliad. Now, in boyish fancy, I watched the likes of Achilles, Ajax and Ulysses pass in triumph with aged Priam, proud even in defeat. I believe that day implanted in me a life-long craving for barbaric splendour, for savagery and colour and the throb of drums.

After crossing Rub al-Khali, Thesiger reached in 1948 the village of Muwaiqih in the oasis of Buraimi, the domain of Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan. He looked forward to meeting this sheikh, who was much talked about among the Bedouins, who appreciated him for his open, informal manner, steadfast character, cunning and physical strength:

Zayed is a Bedouin. He knows camels and rides like one of us, he is a good marksman and knows how to fight.

When Thesiger asked for the sheikh, he was told that it was a good idea to talk to him when "he is sitting", i.e. when he was heading a majlis, legislative council or assembly. Thesiger found the sheikh as he simple, traditionally dressed and barefoot sat directly on the sand, surrounded by thirty men. When he saw Thesiger approaching, Sheikh Zayed got up and invited the Englishman to sit down on a rug in front of him, while he respectfully sat down on the sand again.

He had a strong, intelligent face, with steady, observant eyes, and his manner was quiet but masterful. He was distinguished from his companions by his black head-rope, and the way he wore his head-cloth, falling about his shoulders instead of twisted round his head in the local manner. He wore a dagger and cartridge-belt; his rifle lay on the sand beside him.

Thesiger and Sheikh Zayed became good friends. He lent the Englishman his famous white camel Ghazala. Thesiger returned to Muwaiqih on several occasions and stayed there for extended periods. On one occasion, he followed Sheikh Zayed and his men during a several-week long hunting expedition, when Zayed displayed his great familiarity with all the intricate elements of falconry. He explained to Thesiger that hunting with falcons is the noblest sport in existence, since an experienced falconer feels united with his falcon. He sees and thinks like the hunting bird. This is a completely different feeling than aiming at an animal and shooting it down with a rifle. Just as Dr. Müller at the Abu Dhabi Falcon Hospital Thesiger got he feeling that an avid falconer considered his favourite falcon almost as a family member. Falconers slept with their falcons perched by their beds, and when Zayed’s men sat talking with Thesiger, they had often brought their falcons along with them, caressing and whispering to the birds.

When Thesiger in 1977 met Sheikh Zayed for the last time, he had become one of the richest men in the world, but according to Thesiger Zayed constituted to be just as respectful and politely accommodating as he had been thirty-five years earlier. Although he now lived in a palace, Zayed was still surrounded by his falcons and as often he could tried to ride out for falconering in the desert.

As was the case for Sheikh Zayed, Frederick II of Hohenstaufen's falconry was the result of a centuries-old tradition. His Norman Viking ancestors had been avid falconers, something that several runestones bear witness to, for example the Norwegian Alsted Stone.

At the Böksta Stone close to Swedish Uppsala, we discern how a mounted hunter, followed by a man on skis, kills a moose attacked by his dogs and falcons. On top of the stne is a depiction of a hawk with mmenasing claws.

This depiction makes me think of the Swedish landscape Jämtland’s strange coat of arms, based on a seal created in 1635 by order of the Danish king Christian IV, though the difficult-to-interpret motif may be much older than that. I wonder if the coat of arms might be related to the picture on the Böksta Stone, which is said to be a representation of the ski- and hunting god Ull, whom the Danish chronicler Saxo Grammaticus (1160-1206 CE) is telling us about.

In Nordic myths and legends, there were plenty of birds of prey. The Danish king Rolf Krake is said to have had a hunting hawk named Hábrók, who during a battle near Uppsala is said to have killed no less than thirty of the Swedish king Adil the Mighty’s hunting birds. Like Normans and Mongols, the Vikings thus seem to have brought their falcons with them in battle, as well as in everyday life.

The Norwegian king and later canonized Olav Tryggvason, who by the way was born in Kyiv and there converted to Christianity under Valdemar I, is said to have had a violent temper. He angrily grabbed his sister Astrid’s beloved hunting hawk and plucked the feathers from it after Astrid had refused helping him to propose to a woman who would allow him to enter into an alliance with one of his many enemies.

However, the Russian icon below does not depict Saint Olav, but the saint Tryphon, whose name means "softness/sensitivity". In Orthodox Christianity, Tryphon is worshipped as a protector of birds and prayers are directed to him asking for protection against attacks by rodents and grasshoppers. Before he became a saint in the 200s, Tryphon took care of geese in the Phrygian town Kampsade, but when the Viking Valdemar I introduced his cult in Kyiv, he became a protector of falconers and carries a merlin.

Incidentally, in Nordic legends, hunting hawks are mentioned more often than falcons, which were used more by Normans and Russian Vikings. This was because the more expensive and better-regarded falcons hunted in the open, while in the deep Scandinavian forests, hawks were much more skilled hunters. It is mentioned that the northerners also used owls as hunting birds.

King Gautrek of Västergötland always had his hunting hawk with him and when his beloved wife died, he left the throne to his son and sat mourning on her burial mound, while the hawk brought him food.

Birds of prey are often found in Viking graves, with both deceased men and women. These animals were probably their beloved hunting birds, but the practice to bury them with their masters might also have had a religious significance. In Norse mythology, birds serve as messengers and link humans with different worlds, not least the realms of life and with those of death. Famous are the ravens of the Norse god of death and wisdom, Odin – Hugin and Munin, who carried him messages from all over the world and whispered in his ears. Hugin means “thought” and Munin “memory”.

These two ravens also had a sinister aspect in connection with the fact that they were scavengers and thus also connected to Odin’s role as a feared god of death. The Icelandic poet Torbjörn Hornklof wrote in a poem to the Norwegian king Harald Hårfagre:

Croaking ravens, say,

whence have you come,

with bloodied beaks,

early in the morning?

Flesh stick to claws.

From throats –

foul cadaver stench.

This night you alighted

within a harvest of corpses.

.jpg)

On top of the crown of the world tree Yggdrasil sits the eagle Hreasvelgr, the Corpse Devourer, by flapping his wings he brings deadly tempests. Like Odin, Hreasvelgr has his trusted messenger and informant, the hawk Väderfölne, who rests upon his head.

Hreasvelgr has a twin, the eagle Are, who on behalf of the goddess of the Abyss of the Dead, Hel, picks up those who have been sentenced to death by the Thing, governing assembly among the Vikings, and brings them down to down to the excruciation pits in Helheim.

Birds know and see more than humans, something the hero Sigurd Fafnersbane experienced when, after killing the dragon Fafner and on the advice of Fafner's treacherous brother Regin, was frying Fafner’s heart in open fire. Regin wanted to eat the heart as a reward for helping Sigurd to kill Fafner. However, when Sigurd with his index finger touched the fried surface of the heart and then put it in his mouth to taste, he heard sparrows chirping in a bush

– Sigurd is sitting there frying Fafner’s heart. If he were to eat it himself, he would be the wisest of all humans.

The quest to become one with the birds, and especially with the falcon, this amazingly skilled hunter, is something that has crossed the mind of several men and women who have breeding and training hawks and falcons. The Vikings brought their hawks and falcons across, bringing them with them on travels to Russia, Ireland, England and Normandy and if they seettled there they continued with their falconry.

Wilhelm the Conqueror was an avid falconer and on the Bayeaux tapestry, which tells of the Norman conquest of England, several falcons and hawks are depicted. The descendants of the Normans carried their falcons further on to Sicily and the birds also accompanied them on their crusades. In the Outremer, the Crusader States, the Norman aristocrats for certain encountered like-minded Muslim potentates who just as them were avid Falconers, and they they did exchange their interests and experiences.

The Norman-German emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen claims in his sumptuous book De arte venandi cum avibus, On the art of hunting with birds, that falconry is the most refined sport in existence. It is a way to get to know and become one with nature, a spiritual exercise that also is a form of meditation, an art-form and a science. The traditional hunting with weapons and dogs appeared to Frederick as brutal and tumultuous, falconry, on the other hand, was based on a subtle interplay between bird and hunter creating a relationship between man and nature, reaching its most exquisite dignity in the falconer’s art, where he, his horse and dogs all become subordinates to the noble falcon.

For Frederick his admiration of birds of prey almost becomes a symbol of Cosmos, a powerful life force emanating from an unaltered, unbound nature. He regards birds of prey as aristocratic beings associating them with earthly rulers, almighty princes like himself – the German-Roman Emperor, the most powerful ruler of of this world.

Such thought reminds of the role of the falcon in ancient Egypt. There the falcon god Horus, the son of Osiris, was the maintainer of universal order. His all-percieving eyes were likened to the life-giving sun and the time-controlling moon. Horus was intimately connected with the Pharaoh, the earthly ruler as guarantor of cosmic and accordingly also human order. The eye of Horus became the symbol of all Egypt, of the life-giving Nile, of an orderly Cosmos, of the annual Nile floods, of rain and budding fertility. Horus appeared in symbiosis with Pharaoh and was thus identified with him, while the falcon god acted as the ruler's divine protector, a guarantor that he was under the protection of the Cosmos. A way of thinking which seems to fit well with the Christian notion of Jesus Christ, who is simultaneously regarded as God the Father and his Son, heavenly maintainer of justice and order, a protection against evil and the forces of chaos.

Frederick could in many ways be likened to a pharaoh. Like such a ruler, he lived in harmony with nature. Pharaoh ruled over nature in the form of his control of the Nile’s annual floods, which under his supervision were regulated by organized work and constructions of dams and canals, while he, in his own glory and power, as well as Cosmo’s guarantor built temples for the gods and palaces to himself. Frederick was also an observer of nature's changes, and as one of the world’s first environmental conservationists he set aside large tracts of land, which were to be protected and left untouched for the benefit of wildlife. An initiative that may be linked to his immersive interest in falconry. Frederick wanted to preserve natural areas so that the birds of prey could thrive and multiply.

Likewise, several of his magnificent buildings can be linked to his interest in falconry. I became fascinated by Frederick when I several years ago visited his Castel del Monte. On a hill with views in all directions of the surrounding landscape, shining white against a clear blue sky. A perfect octagon with eight towers, even those with eight sides. Harmoniously and majestically the castle dominates its surroundings. Like a huge imperial crown, it is set on top of a flourishing hill, a symbol of the emperor’s power and control over his reign. However, Castel del Monte is actually neither a castle, nor a palace. It lacks a moat and a drawbridge. In fact, it is an oversized hunting lodge, from which towers Frederick was able to observe the flight of birds of prey and release his own hunting falcons.

Frederick II was in many ways a strange man. In his basic book The History of Biology, which was published between 1920-1924 and translated into a variety of languages, the Swedish botanist Erik Nordenskiöld concisely summarized Frederick’s personality and contribution to biology, which he considered to have been of great importance for ornithology as a science:

Italian in his upbringing, semi-oriental in his habits and way of thinking, he gathered around him learned men from both East and West. He had Aristotle’s writings translated from Greek into Latin. Fredrik’s writing about falconry is so much more than just an account of hunting, it is a comprehensive account of birds' anatomy and habits.

The remarkable Frederick II, who during his lifetime was called Stupro mundi et innovator, Miracle of the World and Innovator, was during his fifty-six years of life almost incomprehensibly active in a number of areas. His many and varied achievements were far from being limited to falconry and his learned observations of and explanations about the life of birds. Frederick’s political career was characterised by disputes over his German, Italian, and Oriental claims, and was marked by constant sieges, battles, and crusades, born out of endless intrigues of a religious, social, and geographical nature. Particularly prominent were his ideological and political clashes with the pope. Frederick could be likened to a storm-carried bird of prey flying above the centre of Europe and the the Levant.

Judged by a modern yardstick, he was also a frivolous pleasure seeker, unfaithful and tolerant, with a vast amount of concubines who in his palace in Lucera, in accordance with oriental custom, were kept in seclusion and supervised by eunuchs.

He wrote about and studied mathematics, architecture, natural sciences and philosophy, reading and speaking Latin, Italian, German, Arabic, French and Greek. One of his special interests and expertise was medicine and he reformed the ancient medical school in Salerno, while he decreed that all medical doctors had to be examined and registered. In 1224, he founded the University of Naples, the first in Europe with established statutes and curricula. Music and literature flourished at his court and together with Muslim and Jewish sages he explored the mysteries of nature, not least through autopsies of humans and animals. His sceptical, practical and inquisitive character was formulated in one of his mottos Ea que sunt, sicut sunt, that which is, is as it is, a critique of theological hair-splitting. He was engrossed in nature studies. As soon as time was given him away from all the political struggles, wars and intrigues, he sought out nature.

In Ferderick's bird book De Arte Venandi Cum Avibus, there is a random picture of a man who has taken off his clothes and swim in a lake, or pond. Maybe a portrayal of Frederick himself. How he relaxes from all his worries and striving. The picture makes me think of a picture of Noman Rockwell showing how on a hot summer day travelling salesman has left his car to take a refreshing dip in a river.

Frederick intensively studied the behaviour of animals in the wild, as well as in captivity. He owned a large exotic menagerie with elephants, lions, cheetahs, dromedaries, camels, monkeys, a variety of birds of prey and most amazing of all – a giraffe, a white peacock and a polar bear. During his numerous travels Frederick often brought with him, as in a circus entourage, animals from his zoo. Of course, since it amused him to deal with the animals, but also to attract and impress other potentates. It happened that he passed through towns and villages, exposing his exotic beasts animals as if they were part of a circus spectacle.

The giraffe was a great success throughout Europe, while the white peacock and polar bear impressed the Muslim potentates he negotiated with in Palestine – he managed without bloodshed to guarantee that the holy sites were reopened to Christians and he became, with the consent of the Muslims, in any case of their temporary rulers, King of Jerusalem. He obtained his giraffe from the Caliph of Cairo, in exchange for his polar bear.

A great admiration for Frederick lives on, especially in southern Italy where he is hailed as the First European. However, this enthusiasm for the German-Roman emperor is not shared by the modern of the crusade chronicler, Steven Runciman, who wrote:

His was a handsome man, not tall but well-built, though early inclined to fatness. His hair, the red hair of the Hohenstaufen, was receding early. His features were regular with a full, rather sensual mouth and an expression that seemed kindly till you noticed his cold green eyes, whose piercing glanced disguised their short-sightedness. […] He was well versed in philosophy, in the sciences, in medicine, in natural history, and well informed about other countries. His conversation, when he chose, was fascinating. But for all his brilliance, he was not likeable. He was cruel, selfish, and sly, unreliable as a friend and unforgiving as an enemy. His indulgence in erotic pleasure of every sort shocked even even the easy standards of Outremer [the Middle Eastern crusader states]. He loved to outrage contemporaries by scandalous comments on religion and morals. […] He saw no harm in taking interest in other religions, especially Islam, with which he had been in touch with all his life. Yet no ruler persecuted more savagely such Christian heretics as the Cathars and their kin.

Behind everything and everywhere was falconry, during Frederick’s travels, his conversations and wars. At one point, a siege ended in disaster as Frederick and his entourage left their camp under inadequate surveillance after embarking on falconry. The enemy broke the siege and destroyed Frederick’s camp. During his free time, Frederick studied the birds and wrote on his De Arte Venandi Cum Avibus, read the works of Arabic falconers and discussed their findings with the Muslim scholars he had in his service, it is possible that he also drew the book’s unique illustrations because he was also known as a knowledgeable artist.

Although the bird reproductions are far from being as detailed and realistic as those of Rudbeck, Audobon and the von Wright brothers, they have a decorative and unique charm.

It is far from only falcons and hawks that Frederick described and depicted.

He also presented the people who cared for and trained the falcons.

He described how the hunt was carried out and how the riders leave their castles at dawn. It was mainly falconry on horseback that fascinated Frederick.

The German-Roman emperor did through his interest in falconry probably strive for a sense of liberation within his multifaceted existence. It is possible that he, like several other bird fans, identified with his hunting falcons – dreamed of becoming like a falcon. Someone who definitely seemed to wish for this was the solitary, myopic and singular John Alec Baker (1926-1987). It may seem that this man was the exact opposite of the powerful, well-known and admired Frederick II of Hohenstaufen – a fairly anonymous clerk at The Automobile Association's, AA’s local branch in Chelmsford, the capital of Essex County, north-east of London. AA provides vehicle insurance, driving lessons, crash protection, loans, car advice, and road maps. J.A. Baker lacked a driver's license, he did not even have a TV in the frugal home he shared with his wife Doreen in central Chelmsford. Doreen also worked at AA. The couple was childless and John Alec remained in Chelmsford all his life. Even his wife described him as “something of a hermit”.

But, there was something that united John Alec Baker with Frederick II of Hohenstaufen and Sheikh Sayed of Abu Dhabi – the falcons. This despite the fact that he never owned or tried to tame a bird of prey. Like Frederick II, Baker obviously wanted to be one with nature and with great patience he approached the peregrine falcons he was fascinated by. According to him, the peregrin regarded all other beings as threatening, as prey, or even harmless. It was especially difficult for a human being to appear as an inoffensive being, because to the animals we appear as killer “stinking of death. We carry it with us. It covers us like frost. We cannot tear ourselves away from it.”

It was important to approach the extremely astute peregrine falcon as quietly and unnoticed as possible:

To be recognised and accepted by a peregrine you must wear the same clothes, travel by the same way, perform actions in the same order. Like all birds, it fears the unpredictable. Enter and leave the same fields at the same time each day, soothe the hawk from its wildness by a ritual of behaviour as invariable as its own. Hood the glare of the eyes, hide the white tremor of the hands, shade the stark reflecting face, assume the stillness of a tree.

Baker wanted to be as close to the peregrine falcon as possible. He had no desire to own it, to master it. It seems that he instead wanted the falcon to dominate him, almost like an unrequited love, a passion. Baker enjoyed and was tormented by this hopeless love, bound as he was to an awkward, unsuitable human body. A spectator who tried to think like a falcon, to be like a bird of prey, but utterly unable to leave his human body behind, to deny his essence as a human being, his human distinctiveness. It is not possible to fly, to see, to feed like a falcon. Baker seems to have avoided human company, aware of his extreme myopia and a clumsiness which was exacerbated by an inexorably aggravated rheumatoid arthritis. During his childhood he had been ill and as a teenager he was after a nervous breakdown admitted to a hospital for three months, the result of an unfortunate love story.

As often as he could, the extremely myopic John Alec walked, or cycled, out into the fields east of Chelmsford. Along the lush banks of the river Chelmer, he reached Essex’s fertile and gently undulating agricultural landscape, sloping towards the mouth of the Blackwater River, by the shores of the North Sea.

With great patience and sharp observation, John Alec followed the bird life through his binoculars. By correcting his unfortunate myopia the binoculars endowed him with something resembling a “falcon’s vigilance”.

In open fields and swamps John Alec thoroughly studied the peregrine falcon’s patient watchfulness, its flight, its habits, its hunting, bathing, and mating. In his book, like Brusewitz and Lord Grey, John Alec meticulously recorded the changes of nature, the shifts and light of the days and especially the dawn; the weather, the wildlife, the scents and the plants. As a common thread through his dynamic and occasionally metaphorically exaggerated depictions, which largely follows day after day from October 1962 to April 1963, there is the constant presence of the peregrine and John Alec’s almost total identification with the bird.

In detail he describes the peregrine’s hunting behaviour. Investigating remains of its prey, which condition he carefully records, in detail describing how the peregrine had torn its victim to pieces and what parts of its flesh it has devoured. John Alec described a world where the existence of birds of prey is characterized by various forms of killing. His accounts are almost completely free from the propensity for a humanization of animal behaviour that often accompanies romantic depictions of nature.

In fact, J.A. Baker’s ten years of diligent study of the peregrine falcon is a thorough, though not entirely accurate, distillation of what takes place during an autumn and winter during which he realized his intention to study the peregrine as detailed as a lone human being was capable of:

Wherever he goes, this winter, I will follow him. I will share the fear, and the exaltation, and the boredom, of the hunting life. I will follow him till my predatory human shape no longer darkens in terror the shaken kaleidoscope of colour that stains the deep fovea of his brilliant eye. My pagan head shall sink into the winter land, and there be purified.

Fovea is a depression in the retina of the eye’s centred vision. In a peregrine falcon, the fovea is much more developed and effective than in humans. J.A. Baker’s (it's typical of John Alec to hide behind the initials J.A.) the mentioning of the fovea is symptomatic of his detailed descriptions. It might seem to be tiring and too cumbersome for someone who has not personally experienced the subtle shifts of nature, but for such a person Baker’s writing style might have an almost hypnotic effect.

In his strange book, John Alec hardly says anything about himself, other than his observations of landscapes and birds, his concern about human’s reckless damage to nature and their guilt for the extinction of peregrine falcons. Occasionally there something that may be described as anxiety, even contempt,occurs while Baker fumes about human’s damaging encroachment on nature. John Alec’s longing to become a peregrine falcon often returns in text:

I shut my eyes and tried to crystallise my will into the light-drenched prism of the hawk’s mind. Warm and firm-footed in long grass smelling of the sun, I sank into the skin and bones of the hawk […] like the hawk I heard and hated the sound of man, that faceless horror of the stony places. I stifled in the same filthy sack of fear.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Such a longing to become a bird has often been described in literature and film. While teaching at the International School in Hanoi for a time, one of my colleagues was Camille Du Aime, a large American lady who grew up on a riverboat on the Seine in Paris:

It was a rather miserable and leaky boat. I cannot say I enjoyed it. My parents were bohemian and while I was with them my father tried to make a living as an artist. He had traumas after his participation in World War II and tried through his art to drive away his demons. It was only at long last he found his right element in writing novels. He became rich and famous, but then it was too late for me.

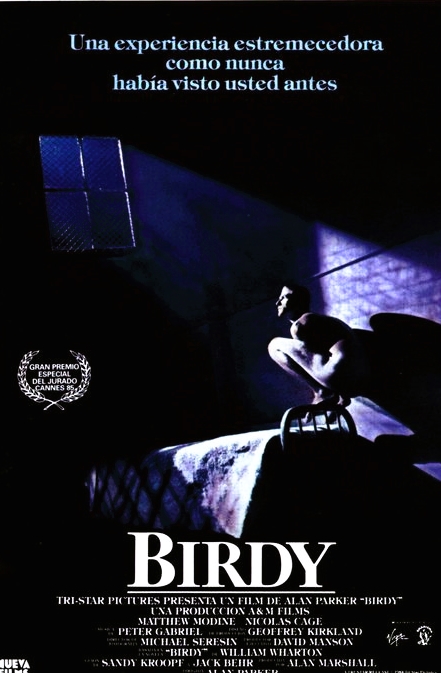

Camille's father, Albert William Du Aime (1925–2008), wrote under the pseudonym William Wharton and Birdy, his first novel, written when he was over fifty, became an instant success and like his following novels Dad and A Midnight Clear, Birdy became a critically acclaimed film (Wharton published more than ten books).

Birdy deals with a sensitive, somewhat neurotic young man who dreams of being free as a bird. Typical of his behaviour is when, after a clumsy and unsuccessful act of love with a beautiful girl, he returns home to a birdhouse he had built in his room and lying naked there imagines how he flies around in his room, through the house and out into the world.

After being summoned to the war in Vietnam, Birdy is wounded in the face and then suffers a severe trauma, is admitted to an asylum where he, through his bird fantasies, builds a mental wall around himself. A wall that not only excludes him from painful war memories, but also from all dealings with other humans and a normal life.

The talented film director Alan Parker, who made the film Birdy in 1984, called Wharton’s book a “wonderful story” and initially wrestled with how to portray it:

I did not know how I could take the lyrical tone of the book and turn it into cinematic poetry, or if an audience really wanted to see such a work.

At the 1985 Cannes Film Festival, Parker's film won the Grand Prix Spécial du Jury.

Birdy and several other works, both novels and scientific accounts,

as well as films, describe human affinity to birds, and especially falcons and hawks.

Alejandro Iñárritu’s multi-faceted film Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) has, through its ability to connect realism with an inner drama affecting reality and thus reshaping it, has by some critics been considered as a successful attempt to transfer Latin American magical realism into film. Iñárritu’s movies has furtermore been compared to Fellini’s 8 ½ since it depicts the world of an artist/director, both from the outside and from within, and how a writers’ block is transformed into successful art.

Iñárritu explained:

What this film talks about, I have been through. I have seen and experienced all of it; it’s what I have been living through the last years of my life.