FROM MALI: A lesson in tolerance

At night, even when the moon is not there, or maybe because of that, the sky sparkles with the twinkling light from a myriad of stars, high above the dry savannah north of the Niger River. Since the villages lack electricity and lighting, the sky becomes more evident than it is in big cities. An enormous sphere spans high above us ‒ The Sheltering Sky.

With my friends Mamadou and Seydou I sat outside an unpainted concrete house a few miles north of the town of Markala in Mali. Seydou spoke excellent English, which he had learned at a university in Algeria and acted as my interpreter. With Mamadou I had to converse in my poor French. Mamadou, who was an anthropologist from the Université de Bamako, asked me:

- Your name, Lundius, does it mean anything?

- I believe it means "from Lund".

- It is a city in Sweden, is it not? There is a university?

- Sure, you know about it?

- Yes, I have a friend from Lund. Maybe someone you know.

I laughed:

- I don´t think so. You see, Lund is a fairly large city and it is many years since I lived there.

- But, you read History of Religion. Right?

- Yes

- My professor at L'Université de Bamako is a historian of religions from Lund. His name is Tord Olsson.

My jaw dropped. Tord was a good friend. He had been my thesis supervisor and although I rarely saw him, we were anyhow in contact once or twice each year. Tord who died last year was one of the four, or five, teachers whose friendship and teaching really had meant something to me, who have influenced the course of my life. I did not know Tord was a teacher in Bamako. When he taught me, he had recently lived among the Masai of East Africa. Nevertheless, Mamadou´s information made me remember that Tord a few years ago had told me he had been initiated into a secret society among the Dogon people of Mali.

- Tord! He is a good friend of mine. Is he in Mali!

- Tord comes here at some point every year and organizes a couple of seminars at my university, let´s call him up, suggested Mamadou.

Modern times! At nine o'clock in the evening within a godforsaken village far out in the middle of nowhere, I spoke over Mamadou´s mobile phone with Tord Olsson in Lund. Sometimes the world is infinitely large, sometimes it is very small. Another day had passed in mysterious Mali. I had come there to carry out a sociological study prior to the establishment of a large sugar industry with surrounding plantations, I may write about that another time, now I want to tell you about another meeting in Mali, mostly as an effort to remember it.

Four million people speak Bambara and they live mainly in Guinea, Senegal, the Ivory Coast, Mali and Burkina Faso. They have a rich culture and in the areas above Markala I have met with people who told me legends about the legendary kings Sundiata and Mansa Musa, who during the Middle Ages ruled Mali's great kingdoms, with their mosques, gold and libraries.

The villages of the scorched landscape I moved about in were all fairly miserable, but the handsome women and men who lived there, with their erect posture, colorful and tasteful costumes – the West African boubous; ankle-length, wide sleeved kaftans and stylishly arranged turbans - made me think of ancient peoples, like Greeks or Persians. An impression that was reinforced when I during my days in Seydou´s company sat in the shade of some baobab tree and with his help talked to laid-back village elders, who accompanied their calm voices with well-balanced gestures by their long, slender hands. However, it was a threatened society we found ourselves in:

- The desert is relentlessly approaching, soon it will devour our fields. We are becoming more and more. The millet cannot feed us anymore. Our young people are dying on their way to distant lands, hoping to find a way to support themselves, because here they cannot survive.

A year after I left the area it came under threat from marauding Jihad warriors, equipped with jeeps and machine guns they stormed in from the deserts. French troops secured the huge bridge over the Niger River and halted the Jihadists´ approach only a few miles beyond the villages I had visited.

The Islamist fighters were a motley crew gathered around a core of Al Qaeda warriors, who had served as mercenaries in crumbling Libya. Fanatical and armed to the teeth, they had dragged with them Tuareg fighters from the deserts in the north, who dreamed of establishing a state of their own - Azawad.

When Mali's Government collapsed after a military coup, the Islamists conquered the legendary Timbuktu and moved towards the capital Bamako. France decided to send in 3 000 troops to its former colony to support Government forces in their fight against the Jihadists. After mirage planes had bombed the opponents and the bridge over the Niger was secured the government troops and their French allies succeeded in gradually chasing the Jihadis from the vicinity of Markala and eventually chase them from town to town along the Niger until they finally conquered Timbuktu´s airport on 28th January 2013 and the Jihadists without a fight disappeared back into the desert.

The Jihadis´ big mistake was probably the same that befall most fanatics – because of their rigid attitudes people turned against them. It was reported that the forces, who called themselves MNLA (National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad) and Ansar Dine (Defenders of the Faith) began to "run amok" within the conquered areas; soldier hordes became guilty of gang rape, forced recruitment of child soldiers and summary executions. They raided hospitals, hotels and stocks of goods and food, including the UN food storage in Gao and Timbuktu with more than two thousand tons of grain and other foodstuff, and yet they cut off the hands of thieves, for example in the city of Ansongo where a desperate crowd of people in vain begged for mercy for the accused. In the occupied Timbuktu and Gao the Ansar Din militia forbade alcohol, football, video games, Western and Malian music and punished women who dared to turn up with unveiled heads. In the city of Aguelhok they stoned a man and woman to death, accusing them of harboring illegitimate children.

I was astounded when I at UNESCO in Paris heard about this mayhem. I had experienced Mali as a quiet and secure place, far from the fanaticism that Europeans now seem to associate with Muslim countries. While at UNESCO I was reached by the news that Jihadis were destroying World Heritage of Timbuktu, tearing down age-old mausoleums erected in memory of Muslim saints, claiming they were abusive to Muslim faith.

In Timbuktu, fanatics also yielded to the despicable custom of other totalitarians, namely book burning. UNESCO had with financial support from Norway, Luxembourg and Kuwait, renovated and built a library and research center, the Ahmed Baba Institute, which had collected more than 20 000 manuscripts in Arabic and local languages. Most of the manuscripts, and wooden boards used for writing, derived from the period 1300-1500. When the Institute was turned into barracks for the Jihadists, only a fraction of the vast collection had been scanned as part of a comprehensive project designed to record and preserve the entire collection. Jihadists burned several invaluable books and manuscripts. By the middle of March this year, UNESCO has initiated an extensive restoration work in Timbuktu, but it has not yet been determined how extensive the losses in the Ahmed Baba Institute have been.

I think of the library of Timbuktu as a symbol of the age-old traditions and popular religiosity that still live on in Mali, demonstrated by the exquisite Bambara art and Mali's rich musical life. This made me ask Seydou if he could put me in contact with some of the region's most respected marabouts.

.jpg)

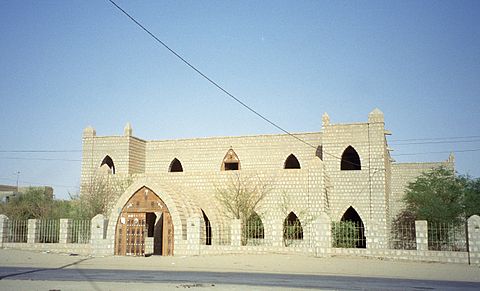

A few years earlier I had met some marabouts in Senegal and I was curious about them, especially since a Frenchman working for the sugar mills consortium had told me that marabouts were nothing more than a worthless bunch of old drunkards who abused young boys who labored for them. He was referring to the so-called talibes, youngsters who often lived adjacent to marabout households and as a payment for Qur'an teachings worked in their master´s fields. West African marabouts often serve as imams, preaching in and taking care of mosques, but they can also be teachers, or itinerant preachers. Many belong to certain teaching institutions, often various Sufi orders, and some of them are even worshipped as saints. Seydou promised to put me in touch with one of the district's most respected marabouts.

One day, the venerated marabout turned up in the enclosed yard of the house where we hung out and using Seydou as interpreter I spoke a couple of hours with him. The marabout, who could be about seventy years old, belonged to a family where the marabout dignity had been passed down from father to son. He was an educated man, knew Arabic and had several times been on pilgrimage to Mecca. When we started talking, I was slightly confused because Seydou gave brief summaries of what appeared to be long harangues in mandé. Finally, I asked Seydou:

- But, Seydou, are you actually translating everything the man says?

A slightly embarrassed Sydou replied:

- I try to summarize it. You see, he talks a lot of nonsense and I think it is somewhat embarrassing for both of us.

- Well, even nonsense can be interesting. What was he saying right now? Can you try to have him repeating it and if possible translate it word by word?

- He said that there are people living on the moon, but we all know that no humans can live up there.

I had asked the marabout about his opinion about fundamentalists' views when it came to the right interpretation ot the Qur'an. Seydou once again turned to the marabout and they spoke intensely with each other. The marabout gesticulated excitedly, while he repeatedly turned to me, smiling broadly. He apparently agreed with Seydou that he would speak slowly and that Seydou after one or two sentences would translate his words as accurately as possible. As I had imagined, the conversation turned out to be very interesting. What the marabout, among many other things, told us was that fundamentalists interpret the Qur´an as if they were living on the dark side of moon. They carefully read all what is written, but since they find themselves in the moon's cold shadow they cannot conceive the sun's clear light or feel it´s warmth:

- It's not enough to read and interpret what God says, you have to experience the kindheartedness of his love and learn to see life in the light of the abundance he in his mercy bestows on us all.

It was beautifully said and the marabout continued to impress me. He took my hand and confidentially leaned forward:

- Young fundamentalist hotheads do not understand that words are not enough for understanding the world. Time is a strict master and it has taught me a lot about what is right or wrong. Experience has made me humble. Fundamentalists state that we are not allowed to do certain things, because they are either not found in the Qur´an or revealed by God through his Messenger, may peace be upon him, and thus the fundamentalists, on their own accord, tell us what to do and not do. But, I say that of course everything that the Qur'an tells us is true, it is truly the word of God. His Messenger, may peace be upon him, speaks God´s word to all people of this world, in all places, all the time. He speaks to us, here and now. How can anyone then tell me that God wants us to live exactly as they did in the time when the Messenger, may peace be upon him, walked on this earth? The Messenger, may peace be upon him, wanted change for the better, not for the worse. God has given us all a free will and I am sure he wants us to choose what is good for all of us. However, he will not force us. Free will means that we choose to either reciprocate the love of God, or refrain from doing it. You cannot force someone to love. God is righteous. He does not want us to choose things that hurt others. God is merciful and just.

The marabout listened intensively while Seydou translated his words into English. Of course, he did not understand anything of it, but nevertheless it was as if he wanted to check if Seydou got everything right. The conversation dragged on and finally the marabout summed it all up:

- We have talked about truth and lies. About what I believe to be God's will. The Fundametalists are dangerous. They are against free will. They do not know what love is. They do not want people to think. They would like to hinder people from making their own free choices, to choose freely. I believe the Fundamentalists act against God´s will. They put themselves above God. In Islam this is a very serious sin. They destroy the people. We cannot be sure of anything, only God knows. However, I can tell you what I believe. I believe that God speaks to all people through the Qur´an, but in my dreams, he talks to me.

After the marabout had left us, I and Seydou reflected on what he had told us:

- It was fine when you suggested that I ought to listen carefully to what he had to say. You see, he expresses himself in a strange manner, but when you grasp the idea behind his words it all starts to fall in place. He is actually a very interesting man. I never really understood it, explained Seydou.

A few days after our meeting with the marabout, Seydou had made contact with one of the few Christians who lived within the district. A lean, serious man, speaking slowly and clearly. We met him in the village school, he was president of the school association.

- There are not many Christians here. In my congregation there are only seven of us.

- Seven? That was not much of a congregation.

- Here all are Muslims. Why would anyone become a Christian? They ask themselves how they would benefit from it. "You are black like us. Poor as we are. You are not even white and rich. What can you offer us, that we do not have not already?” You have to understand that as a white man you always have someone backing you up; your country, your organization, your money. I have nothing but God and Jesus. My Church is headquartered in Bamako. We are all from Mali.

- Did you convert from Islam?

- No, no, if I had been a true Muslim I would probably never have become a Christian. My father was an animist, our ancestors were animists, I was also an animist. We were all Muslims, but in a traditionalist manner. We belonged to the society of Chiwaras and that affiliation was in a certain sense more important to us than Islam. I became a Christian when I met a missionary in Markala, who explained the suffering of Jesus to me. He told me that a Christian person constantly has to be aware, he must believe in a conscious manner. Otherwise you behave like cattle, you live without thinking, without choosing. I chose Jesus because he is both God and man. He was someone I could relate to, not a group of people, not a book. Ever since I was saved, Jesus has been with me.

- The seven of your congregation, were they Christians from the beginning, or is it you who convinced them to share your faith?

- They have become Christians through Jesus Christ, but they met him through me. However, it was only two years ago they became Christians.

- For how long time have you been a Christian?

- Twenty years.

- And during all that time you have preached Christianity in this village?

- Yes, but no one wanted to listen to me. They said, "You're crazy not wanting to be like us. Why should a Mandé like you become a Christian? You're crazy, you're not white”. They spat behind my back. They isolated me.

- But what happened? How did you become president of the school association? How did you get your seven companions?

- Everything is thanks to the marabout.

- The marabout?

- Yes, he whom we met the day before yesterday, interjected Seydou.

- But how did that happen?

- One evening there was a knock on my door and when I opened it the marabout stood there. He greeted me and said "I have observed you and have realized that you are a holy man. Only someone who has been so lonely and strong as you have been can have such a resilient faith. I believe you and I are the only two men amongst all of us who are closest to God. However, you have struggled for your faith, while I was born to my position. If you doubt God, you do not have to worry about losing people's respect. You do no not have any respect to lose. On the contrary, if I reveal any serious doubts I may lose everything I have. People do not believe in you, but they believe in me. If I would express any doubt people will turn their backs to me. When I suffer hard times, I have no one to turn to. But, I believe in you. You know God. I know God. That is a faculty that you and I share. I do not know if you need me, but I need you. I know you would understand me if I brought my doubts and worries to you. Likewise, you can come to me. If you pray to God for my sake, I will pray to Him for you." Of course, I was moved by the confidence the marabout gave me and I assured him that he had a friend in me. The marabout is a holy man. He is mighty and strong and has now become my support and help in the village. During the Friday prayers that followed our meeting he sent for me. I came to the mosque and he introduced me to the people saying: "This is my friend. He is a holy man. If you respect me, you respect him”. Since then I have become one of all, I was chosen to be president of the school association, while seven other men and women have come to me through Christ.

- Are you all respected now?

The Christian smiled:

- Respected perhaps, but not entirely accepted.

To my knowledge the sugar production was never initiated, too many problems occurred. I hope the Jihadists never reached the villages I visited. Poverty still holds the peasants in its deadly grip, but I hope that the friendship continued between the marabout and the Christian and that the poor peasants around Markala in a not too distant future will have a better life and a more secure existence.

In Mali I often heard about the legend of Sundiata, the Lion King, and the great epics sung about him by the griots, West Africa´s famed troubadours. There are many versions of this impressive tale, but the best I've read so far was Camara Laye (1980), The Guardian of the Word. London: Fontana / Collins. I must also mention the fascinating Malian musical tradition, there are many great artists to choose from, my favorite is Ali Farka Toure, undisputed master of the desert blues.