IN THE WORLD OF ADVENTURE: Encounters with the art of Eric Palmquist and Björn Landström

I had planned to clear the grounds around our house from twigs and fallen leaves. Accordingly, I went outside quite early in the morning. The sky was bright blue, though it soon became clouded and it did not take long before the rain poured down, preventing my outdoor activities.

Back in the house, I made a fire and pulled out a book from the shelf. It happened to be Edward S. Ellis's Ned in the Blockhouse: A Tale of Early Days in the West, this novel, as well as Ned on the River were the only books by Ellis that had been included in Bonniers´s series Immortal Books for Young People, of which I still had some left. I assume that I during my adolescence swallowed almost all of those fabulous novels. At that time it delt like entering another reality. A unique feeling that few other novels have been able to create, either then or later.

I was now reading Ned in the Blockhouse once again, well aware of the fact that I would never again be surrounded by the wilderness of Kentucky and Ohio; ancient forests inhabited by the sad survivors from indigenous tribes who already by the middle of the eighteenth century had been decimated by chickenpox, cholera and typhoid, diseases brought to the West by intruders into the hunting grounds of Native Americans, pushing them aside or brutally killing off those who had survived their tribulations.

Ellis´s books are contaminated by unashamed racism; disdainful views of Native – and Afro Americans. He generally described Native Americans as savages, though he nevertheless provided them with a certain degree of cunning and described them as thoroughly familiar with the natural habitat, in which they had their home. On the contrary he considered Afro Americans as quite kind-hearted beings, albeit clumsy and generally quite dim-witted. Black people, in reality slaves, though Ellis called them "servants", represented the lighter entertainment in his novels.

.jpg)

As in many other novels by Ellis the undisputable hero of Ned in the Blockhouse was the Christian Shawnee Deerfoot. He is true son of the wilderness. Young, handsome, athletic and intelligent he moves silently and swiftly through the woods and is capable of swimming like an utter. Furthermore, Deerfoot is an unwavering friend of all white settlers and trappers, and does not hesitate to betray, or even kill, members of his own tribe to protect the white intruders.

Certainly, already as a youngster I reacted to the trappers Simon Kenton and Daniel Boone, too good to be true, and not least the young, annoyingly perfect Ned Preston. Already then I found Ellis´s depiction of Neds "servant" Blossom Brown to be not only irritating, but outright offensive. This young Afro-American was depicted as a jovial, clumsy and moderately talented glutton, who constantly messed things up for his noble Massa Ned. Blossom Brown´s shortcomings was not due to his youth and inexperience since he shares his laughable traits with the grown-up, “black servant” Jethro Juggins.

Nevertheless, the formidable Deerfoot managed to escape from my disapproval, despite his exaggerated religiosity and unreserved loyalty to racist settlers. Deerfoot was an exceptional human being. He knew the trails of all animals and humans. Just by scrutinizing broken twigs and imprints from moccasins, he knew which tribe of Native Americans who had been travelling through the forests. Deerfoot could mimic the sound of all animals, knew all the scents of the forest and could even move silently over dry leaves, something I often tried to do - an impossible endeavour.

It was the natural habitat in which Ellis´s characters move, how it influenced their actions that caught me. For me, it found its equivalent in the forests of my own, gfamiliar terrain, the forests and lakes of Göinge, with impenetrable brushwood, beech woods, which smooth, silky grey trunks rose from rust coloured leaves and resembled pillars in a cathedral made out of lush, light-green foliage. There were huge moss covered boulders, fallen timber, small streams and just like in the Kentucky and Ohio of Deerfoot, lakes shimmered in the depths of the forest and I could occasionally come across an elk, or frighten a group of deer.

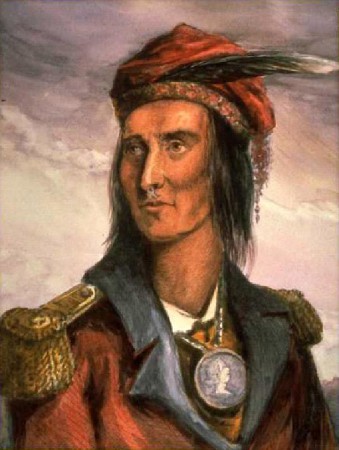

While renewing my acquaintance with Ellis´s novels I did of course notice his flagrant racism and his often rather awkward language, yet I could easily discern what had fascinated me as a young boy. Both Ned in the Block House and Ned on the River tell the story of how a small group of settlers during the so called Tecumseh War 1811 – 1813, becomes cordoned off by threatening natives. During this war white settlers were attacked by the Confederacy of Tecumseh, a network of North American indigenous peoples, who tried to fight off a US government supported colonization after the North American Freedom War. The Confederation´s goal was to push away American troops and US settlers from the so-called Ohio Territory, which lay south of Lake Erie and between the Appalachian mountain range in the east and the Ohio River to the west.

Leader of the Confederacy was the charismatic Shawnee chieftain Tecumseh and he was inspired and supported by the religious teachings of his brother Tenskwawata. The war broke out in 1811 when US troops attacked the central villages of the Confederation. When Tecumseh died in 1813, his movement collapsed.

In Ned in the Blockhouse the colonisers are trapped inside a wooden fortress by the Licking River, a tributary to the Ohio River in north-eastern Kentucky, where another party of white settlers in Ned on the River cannot leave their barge while being surrounded by “blood thirsty natives” on the war path under their formidable leader Tecumseh, Deerfoot´s sworn enemy.

Undeniably, in spite of all their blatant shortcomings, Ellis´s novels still provide exciting reading. Ned and Blossom are in both of the books I recently reread, lost in trackless forests, while vicious savages try to kill them.

While reading Ned in the Block House, I suddenly remembered how I once had encountered a picture of Ned hiding in a tree. I flipped through the book without finding the illustration and then remembered it was in Ned on the River I had seen it. Returning to the bookshelf, I found that particular book and was soon back with a ten-years-old Jan, who invisibly together with Ned Preston clung to a tree trunk while two Shawnee warriors were searching for Ned´s footprints on the ground below him:

… he found he was surrounded by so many twigs and leaves, that he could not be seen from either shore. With an anxiety that can scarcely be imagined, he awaited the issue of his attempt to outwit the red men. He was not kept long in waiting.

Ned looked down at his pursuers, the Shawnee warriors were circling the tree. Even though he was more eager than ever to keep them under surveillance, he shivered from the imminent danger. He feared that if he opened his eyes, the scouts would discover the whites of his eyes. He forced himself to shut his eyes, listen, wait and pray. When he could not use his sight, his hearing was sharpened,

The Shawnees did not have to say anything, they understood each other so well that all speech was superfluous. They acted on their own and if someone discovered something he would certainly not be late in communicating his findings to his companion.

When you are as hard up as Ned Preston, time is slow. After ten minutes, he was convinced that he had been lying in the same position for more than half an hour. During this time he heard nothing that could increase his concern. He nurtured a slight hope that the men had gone away. His anxiety became so excruciating that he had to open his eyes and slowly pull away the leaves with his right hand, carefully glancing over the edge of the branch.

To his horror, Ned finds that at the opposite shore of the stream, a Shawnee looks straight into the tree among whose branches and leaves Ned is concealed, while the warrior´s companion stands in the water just below Ned, looking up at the tree branch he is resting on. The Shawnee below Ned takes a few steps back, constantly facing upwards, but then he happens to walk into a cavity below the water and disappears from sight, when he surfaces again hicompanion laughs heartily and the warrior cannot help bursting into laughter as well. After some hesitation, he wades into the water and joins his companion on the other side of the stream. They walk on and Ned can finally begin breathing with ease.

While I after several years once again was confronted with Uno Stallarholm's illustration, I understood that it was it, perhaps more than the story's intensity, which had stuck with me. When I continued to browse among the novels in my bookshelf, I realized how much their illustrations and covers had impacted me and nurtured my imagination. English and French pictures had been rooted in my subconscious, but also Swedish artwork. I realized how impressed I had been by several more or less forgotten Swedish illustrators, like Uno Stallarholm, Stig Södersten, Gunnar Brusewitz, Douglas Dent, Birger Lundkvist, Martin Lamm, Sven Olov Ehrén, Adolf Hallman, Ib Thaning. The list is long and may be even longer. However, among the absolute best was Eric Palmquist.

It is astonishing that such a professional and hardworking artist as Palmquist does not figure more prominently on the internet. I was unable to find much written about this self-taught artist who, to my mind, almost as much as my favourite authors, has come to represent my perceptions of a wide range of novels. And not only that, Palmquist also illustrated several bird - and wildlife books.

Not least, he created the prototypes for the elegant Swedish banknotes that were in use 1965 to1985.

Equally skilled and fascinating are Palmquist´s hundreds of book covers. My father kept several of them in his bookstand. Palmquist's dust cover art was unique since it did not only adorn the front sides, but the backs and spines as well. Book ledges framed our TVset and when I did not pay attention to the screen I used to let my sight wander across the shelves. Thus, already before I was able to read, I had become fascinated by the spine of The Three Musketeers on which Palmquist had depicted how D'Artagnan was sitting with Mylady on his knee, while a musketeer directed his weapon towards me. I was not disappointed when I later swallowed up Dumas´s wonderful novel and found that it in every respect fulfilled the excitement and fascination promised by Palmquist's dust cover.

Sometimes, I found that the dust covers had indicated more than the novels could deliver. Palmquist did for example encourage me to read historical novels like M.M. Kayes´s Shadow of the Moon, which dealt with the Indian Sepoy Rebellion. However, I had just before I read Kayes´s novel been impressed by Rudyard Kipling´s Kim and this was probably one of the reasons to why I did not find Kayes's story, despite its exciting features, as interesting as I had hoped it would be. Maybe there was too much love story in it. I do not remember and someday I maybe ought to read it again.

Likewise, I felt tricked by Palmquist´s exciting dust cover when I read the American writer Anya Seyton's novel about Katherine Swynford, who in the 14th century had relationships with several influential men and found herself at the centre of crucial events in France, as well as in England, but for me the story involved too many names, complicated intrigues and too much romance.

On the other hand, I was excited by Robert Lewis Taylor's The Great Gold Rush and without rereading it I assume it remains the best Western I have read. Night after night I devoured it before I fell asleep at around three o'clock in the morning.

Robert Lewis Taylor's West was quite different from the place I knew from the Western movies on TV; more tangible and raw and furthermore, it was perceived through the eyes of a young man.

The unknown, exotic, yet intimately and carefully depicted, is something that several of Palmquist's illustrations have in common. For example, his dust cover for the Yugoslav Nobel laureate Ivo Andrić's epos The Bridge on the Drina was a fascinating assortment of Slavic, historical exoticism, which corresponded well to the novel's striking storytelling. During my military service, it kept me awake in front of switchboard and Morse key during long night watches.

The same erudite spirit of place was evident in Palmquist's dust covers for the Romanian author Zaharia Stancu´s novels about freedom-loving Gypsies and cruel landowners,

.jpg)

or for Knut Hamsun´s Nietzchean depictions of how earth was broken and cultivated in the Norwegian wilderness, as told in his Growth of the Soil.

It was not only novels by authors in the Nobel Prize league that Palmquist illustrated. It seems as if he was willing to illustrate whatever he was offered, short stories in magazines, children´s books, as well as local and international bestsellers, he executed all tasks with equal seriousness and empathy. He made the dust covers for novels by folkish and popular writers like Marit Söderholm and Sven Edvin Salje. With great interest I read Salje´s novel about seventeenth guerrilla fighters from my part of Sweden, All Men out of the House, attracted to it by Palmquist's book cover.

He also created the cover of novels by the more respected authors who belonged to what had been labelled the Proletarian School, a literature trend which in Scandinavia had its palmy days during the 1920s and 1930s. Among those highly esteemed autodidact worker authors Palmquist illustrated novels by Moa Martinsson and Jan Fridegård.

Fridegård impressed me with his trilogy about the slave Holme, who lived during the turbulent days when Swedes gradually accepted Christianity. Before giving me those novels my father had consulted with my mother, asking her if it was really advisable that he gave his young son novels that at times indulged in somewhat unconventional descriptions of sex scenes. My mother thought it could not be so particular dangerous and it was furthermore quite probable that I did not understand much of what that was all about. Nevertheless, I appreciated those sparingly occurring parts in Fridegård's novels, though I was even more fascinated by their dark, brutal mood and by reading those and other Fridegård´s novels I became interested in politics and class struggle.

The slave Holme was constantly involved in battles against insolent masters and rulers, at the same time as the novels dealt with something that always has fascinated me, namely religion. Fridegård´s tales admirably described how Christianity challenged the Aesir faith of the Vikings and true to the old Icelandic sagas he depicted the Christians as either meek, or just as brutal as their pagan adversaries.

And all of it was quite exciting for an eleven years old boy. With bloody battles and Viking raids. Something that was excellently emphasised by Palmquist's straightforward illustrations. Through his eyes I could see how women looked for their wounded and killed kinsmen, while enraged men continued to fight each other on blood-soaked battlefields.

Through Palmquist I could also envision the strong and independent women of the Scandinavian Viking age and admire how he depicted slender longships heading for opening horizons.

It was Eric Palmquist's ability to blend into different cultural environments and powerfully depict them from within that fascinated me. Especially his depictions of the wilderness have remained in with me. For example, his illustrations of Jack London´s Call of the Wild and Fenimore Cooper´s The Last Mohican.

In the latter he succeeds in portraying the wildness and ruthlessness of the eighteenth century Indian Wars. His illustrations reinforced James Fenimore Cooper's descriptions of callous massacres, or mortal combat man to man.

At the same time, Palmquist found bold angles and unexpected image compositions, thus creating a sense of documentary presence. Through the unexpected originality of his illustrations I was brought straight into the action of Fenimore Cooper´s exotic universe.

This applies not the least to Palmquist's illustrations to Michael Strogoff: The Courier of the Czar by Jules Verne. When I recently reread it I became fascinated by how Palmquist had managed to add a large measure of drama and depth to descriptions that nevertheless were filled with excitement, though to a certain degree lacking the depth and human presence that I, after reading the great Russian authors, could expect from a story taking place in nineteenth century Russia. Certainly, Michael Strogoff evolves within a landscape and a society where class differences and misery are evident. Where half-civilised Cossacks and Tatars make the courier´s mission extremely dangerous and difficult, an ability they share with arrogant officers and corrupt civil servants. However, Jules Verne, who certainly knew Russia only through his Russian acquaintances, encyclopaedias and atlases, succeeded in telling a thrilling story, though he failed to provide enough authenticity to his characters and also failed to provide enough depth to his Russian scenery. Occasionally Jules Verne falls into the trap of providing rather dry geographical descriptions and generalizations about people and politics. However, through Palmquist´s illustrations we are invited to Petersburg's palace and also meet common people from the multitudes of Imperial Russia, individuals who might just as well appear in novels by Gogol or Dostoyevsky .

Palmquist depicts the thrills and dynamics of Verne's novel. Occasionally he even succeeds in increasing both the drama and exotic sceneries described by Verne. We become surprised by sudden appearances of ferocious bears and blood-thirsty wolf packs

and are confronted with unscrupulous officers, clerks and bandits.

And, strangely enough, Palmquist is even able to convey the specific rhythm that permeates the entire novel. We feel the urgency of the courier when he travels across endless steppes, over snowy mountain passes and vast rivers with trains, troikas, rafts and on horseback.

He travels through snow storms, across deserts and across war torn areas.

He comes under attack from riotous hordes or becomes subjected to time-consuming confrontations with bullying officials serving the Tsar, or various warlords.

With great empathy and detail, Palmquist enters one after the other of classical novels. He mystifies the depths of the sea in his illustrations of Verne´s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

In Palmquist´s illustration for Robinson Crusoe I recognized the mystery and strangeness that through his loneliness were created around the lost sailor .The shipwreck is transformed to a rather eerie fairy tale castle, while Crusoe's hard pursuits are provided with a dignified dimension.

However, Huckleberry Finn's Adventure and Tom Sawyer's Adventures are depicted with a tangible small-town realism. An amused nostalgia permeates Tom Sawyer's boyhood and to a certain degree Huckleberry's and Nigger Jim's cruise along the river, though in the latter we also perceive chilly streaks of mystery and horror.

.jpg)

Especially in Palmquist´s illustrations of Huckleberry Finn we are confronted with the picturesque folklore of small towns along the Mississippi River, but also with the shifting climate and wildlife along the vast river's shores and just as the weather unexpectedly changes, violence may explode and threaten the young men on the raft.

A deep familiarity with the scenery and the people of past communities are also evident in Palmquist's illustrations to Astrid Lindgren's children´s books like Rasmus the Vagabond and Master Detective: A Kalle Blomkvist Mystery, a bygone rural Sweden, with flowering meadows and jolly police constables, is depicted against a barely noticeable fund of poverty and social vulnerability.

To me, Palmquist reaches one of his peaks in depictions of the exotic and foreign. In my opinion, he never fails while doing just that. Like when he takes on one of my all-time favourites - Robert Louis Stevenson's The Treasure Island, a novel filled to the brink with ingredients required to create an unforgettable adventure. It immediately takes off with a mysterious, auspicious introduction with weird, malicious strangers like the pirates Billy Bones and the Black Dog, as well as a blind beggar, who are confronted with solid, local trustees like Livesey and Trelawney, all this perceived through the eyes and mind of the young, witty and adventurous Jim Hawkins. When Jim, in the deceased Billy Bones seaman's chest, comes across a treasure map we know that we going to be thrown into thrilling adventure.

In each chapter Stevenson is able to heighten the excitement, which was of great use to me while I was trying to feed my older daughter, who as a child, to the great despair of her parents, was reluctant to eat the food we offered her. However, she ate while I read The Treasure Island. I stopped reading as soon as she refused to swallow a piece of food. My tactics worked well, like her father my daughter was fascinated by Stevenson's skilfully presented story.

Palmquist managed to capture the mystery of the ocean. How the ship Hispaniola lightens anchor and with filled sails sets out across the sea on its way to adventure.

He catches the days and nights aboard the ship and how young Jim Hawkins at dawn from the ship's forefoot gets a first glimpse of The Treasure Island.

With Palmquist we perceive Jim's fascination with the ruthless old sea lion, Long John Silver. As the youngster are captured by the pirates and join them in their blockhouse, he listens to how old Long John Silver, with his parrot on the shoulder and clay pipe in the mouth, tells secrets and stories about his adventures on land and at sea. In his depiction of this incident Palmquist proves capable of capturing the essence and mood of Stevenson's indomitable book, a pinnacle of adventure and storytelling.

Stevenson's rhythm as he moves between tranquillity and high drama, dark nights and exotic daylight, is mirrored by Palmquist's illustrations. Like when during the pirates' pursuit of the lost treasure, Jim is stumblingly dragged along by the diabolically energetic Long John Silver, who with high speed strides towards the story´s climax.

It is in his depictions of life at sea that Palmquist is at his best. Countless times have I leafed through an anthology called Famous Narrators from the Seven Seas, a book which my father once gave to my grandfather. Grandad´s father had been a skipper in west coast town of Varberg and with his brothers Grandad had in his youth on his father´s schooner sailed across the North - and Baltic Seas and he always felt close to seamen on sailing ships, a fascination he managed to convey to me.

I read Marryat, Conrad, Dana and Melville with great respect and in the Famous Narrators from the Seven Seas I found everything I could ask for. Excerpts from Melville's peerless story about the pursuit of the white whale, which developed not only from detailed descriptions of the prodigious whale hunt, the lives and behaviour of whales, the battles, the wearisome, dirty toil of slaughtering the huge animals, the socialising and loneliness onboard a whaling ship. However, in addition to all that Melville tells us about the state of humanity. Our position in God´s creation. About the vastness of the sea, of human existence in all its aspects; its greatness and its misery.

Palmquist's pictures took me with him high up in the rigs of mighty sailing ships.

and down into congested, cold, humid, and smelly crew cabins, which have been described by the old sea captain Joseph Conrad:

The tin oil-lamp suspended on a long string, smoking, described wide circles; wet clothing made dark heaps on the glistening floor; a thin layer of water rushed to and fro. In the bed-places men lay booted, resting on elbows and with open eyes. Hung-up suits of oilskin swung out and in, lively and disquieting like reckless ghosts of decapitated seamen dancing in a tempest. No one spoke and all listened. Outside the night moaned and sobbed to the accompaniment of a continuous loud tremor as of innumerable drums beating far off.

Palmquist also brought me along with him to the fishing banks of the Northern seas and allowed me to witness the fishermen's toil in blinding, icy storms.

It was not only big sailing vessels boats and fishing boats I was invited to, but decrepit, coal-fuelled merchantmen described by Scandinavian Proletarian authors like Aksel Sandemose, Josef Kjellgren and Harry Martinsson. Martinsson´s short story, A Greek Tragedy, is a wonder of concentrated expressiveness and narrative skill, especially considering that its exciting, unique style was created by a young man with limited schooling.

Martinson was six years old when he lost his parents and as a so called parish child was forced to work as a farm hand, suffering from an existence characterized by social exclusion, starvation and misery. Fourteen-years-old, he ran away from the farm where he served and lived as a vagabond, when he was not caught and sent to educational institutions, from which he regularly ran away.

Sixteen years old, he boarded in 1920 on a schooner destined to Ireland and then spent several years traveling around the world. Lung problems forced him to return to Sweden, where he for several years lived on chance work, when he did not wander around as a vagrant. In 1927, Martinson published his first poem, and in less than a year he had managed to place no less than 69 newly written poems in various magazines. In 1932, he published his first collection of short stories and became an established author.

In A Greek Tragedy, Martinson tells us about the crew life of a dilapidated Greek steamer on its way from Pensacola to Buenos Aires, overloaded with sequoia timber stowed on deck as a several meters high pile that soon begins to lean sideways and gives the ship a dangerous tilt.

Martinson worked a mess boy and his tale brings us to cabins and engine rooms, providing lyrical descriptions of an ever changing ocean, telling us about an innocent romance with the captain's wife and the interaction between crew members who come from all parts of the world. With bravura he then describes how a hurricane strikes the ship on open sea, the timber brake lose and is lost among enormous waves, while three men are washed overboard into their death in the raging inferno of the sea. Martinson probably remembered this dramatic experience when he in his first collection of poems, Ghost Ship, included the following lines:

Have you seen a tramp collier come out of a hurricane—

with broken booms, gunwales shot to pieces,

crumpled, gasping, come to grief—

and her captain gone all hoarse?

Snorting, she puts in at the sunlit wharf,

exhausted, licking her wounds

while the steam thins in her boilers.

He shows us the loneliness and chill among gray, desolate waters, where the infinity of the water joins the sky's gloomt pallor.

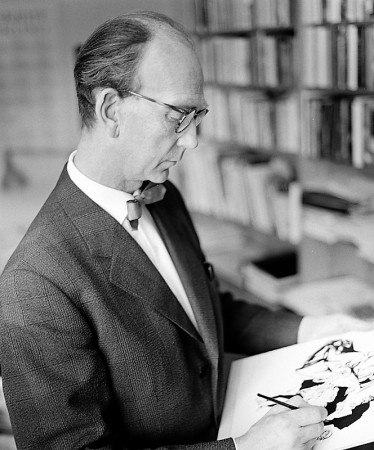

After having so often been fascinated by Eric Palmquist´s (1908 - 1999) art, I became somewhat surprised when I was confronted with his portrait on Wikipedia. I had expected an impressive, obviously audacious, adventure keen person, but instead I found a conventionally attired man, resembling the architype of a civil servant, with retreating hairline, a suit and a bow tie, who with an elongated face and a stern gaze appeared to be sketching one of his numerous illustrations. Palmquist´s mundane appearance made me assume that he like Jules Verne primarily was a desktop traveller, who in his own mind managed to embark on adventures and trace the very nature of the environments he depicted after intense studies of books and pictures – making his performance even more impressive.

After having spent quite sometime in the company of the art of Eric Palmquist, I would like to mention another artist/illustrator who has opened the doors to the domains of imagination – the Finno-Swedish Björn Landström (1917-2002). Like many other illustrators, Landström also wrote novels and historically-oriented books, especially about discovery expeditions and sailing ships. He illustrated his own works and several others by well-known writers, often fairy tales and legends. Especially interesting are his illustrations to the Finnish national poem Kalevala.

Unlike Eric Palmquist, Landström's appearance seems to coincide with the mental image I have made of him, apparently mirroring the famous sailor, shipbuilder, adventurer and scientist he was.

With Palmquist, the artist Björn Landström shares his efforts to meticulous study the context of his illustrations, though in even greater detail, often based on a direct familiarity with the places he depicts, being reinforced by scientifically based studies and prolonged visits to places around the world. However, this does not prevent an imaginative quality of his depictions of historical scenes, which he often described with great, yet chilly drama.

Among his best acievements is The Quest for India, which descrines exploratory journeys from the beginning of historical record up until Columbus's journey to America, which he in detail described in another of his books.

To look at a picture by Landström is like moving back in time, like his image of Phoenician sailors in the process of repairing their ship, pulled up on a beach by The Rock of Gibraltar.

We meet an exhausted Roman legionary, sweltering from heat and thirst in the Arabian Desert.

Roman ships are in Aden's harbour awaiting the monsoon winds that will bring them across the Indian Ocean to India's trading cities.

Olupun, a Nestorian missionary from Syria, is in 781 AD received by Chinese Imperial dignitaries.

Odoric from Pordenone, a lonely Franciscan monk travels in 1328 across the Himalaya on his way Lhasa, to meet with the Dalai Lama, Obassi "for such is the name of their Pope in their language”.

A Moroccan Bedouin watches in 1291 how a Venetian galley passes by the African coast, heading towards an unknown fate.

We follow Landström up to the far North. He conveys exciting theories and insights. As when he tells us about how Irish monks during the sixth century reached the icy seas of the North, where sighted the terrible apparition of Judas Iscariot chained to an island of purest crystal.

Instead of an eternally condemned and plagued Judas, Landström assumes that what the Irish monks had spotted was probably a walrus resting on an iceberg.

Landström also lets us be confronted with the monsters that the Portuguese captain Cadamosto in 1456 had encountered while he sailed up the Gambia River.

Landström lets us also accompany Leif Eriksson when he from his wind-driven ship through ice-cold mists in the spring of 1000 AD for the first time saw the coastline Vineland the Good, i.e. present-day New Foundland.

Landström also takes us on board a Greek ships sailing between the Pillars of Hercules on its way into the Atlantic sea.

By an African coast, sometime during the 1400s, three Portuguese ships rest under the Southern Cross.

And finally, Columbus´s three ships leave the port of Palos de la Frontera, setting course towards the New World.

Looking at illustrations by artists such as Palmquist and Landström, as a youngster I often felt the pull of adventure. Reading the novels and books they illustrated made me understand the meaning of the words of the narrator of Melville´s Moby Dick:

As for me, I am tormented with an everlasting itch for things remote. I love to sail forbidden seas, and land on barbarous coasts.

But such wishes can easily have terrible consequences, so perhaps it is best to enjoy the adventures that art and literature may offer though the craftsmanship of masters like Palmquist and Landström.

Conrad, Joseph (2007) The Nigger of the ´Narcissus´ and Other Stories. London: Penguin Classics. Ellis, Edward S. (2012) Ned on the River. Charleston, SC: Nabu Press. Landström, Björn (1964) The Quest for India: A history of Discovery and Exploration from the Expedition to the Land of Punt in 1493 B.C. to the Discovery of the Cape of Good Hope in 1488 A.D. in Words and Pictures. Crows Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin. Martinson, Harry (1934) Cape Farewell. New York: Putnam. Martinson, Harry (2017) Poetry. https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1974/martinson-poetry.html Sugden, John (1998) Tecumseh: A Life. New York: Henry Holt and Company.