INTERPRETATIONS: Memories, Cucchi and Rimbaud

In school, I was asked by a Swedish teacher "interpret" the poem Lunaria by the Swedish poet Wilhelm Ekelund:

Far from others you seem to stand,

so strange and quiet,

your gaze is yours and cold;

but the depth is heavy with desire.

Your mood is not like others.

Though the sunny gully above you

is filled with buzzing summer,

where thorny rose, lily of the valley

and honeysuckle flame and shiver;

playing in the wind, they flaunt,

they laugh and sing.

I was dumbstruck. I knew the flower, which in Swedish carries the beautiful name Månviol, Moon Violet. My grandfather had told me that despite its name, the flower was not a violet at all. In the green suburb of Enskede in Stockholm, Grandpa had a lush garden. I have in a previous blog post told you about that garden and how Grandpa used to show me his flowers, while describing their peculiarities. The garden was laid out on a slope and a mighty wave of flowers seemed to rise up outside the living room's bay window.

A narrow path, with unevenly placed steeping stones, between which orpines, phlox and aurinia grew, it winded up along the slope through dense flower beds. By the crest, the rock face lay naked under towering pine trees, then it sloped towards a wide ledge that by a wobbly fence was delimited from an intimidating precipice. It was on that shelf that Grandpa had his compost and kept several flowers that thrived in the shade, among them the Lunaria.

Ekelund's poem about the white flower that in splendid isolation rises beneath a crease filled with imposing flowers did for me constitute a living, highly personal image. Why did I have to "interpret" it? The poem aroused thoughts and feelings, was that not more than enough? After me mumbling something about loneliness and companionship, my teacher embarked on a winding discourse explaining how the outsider Ekelund in his poem described an almost religious, inner freedom. How his respect for absolute beauty transformed personal experiences, while opposing them to generally accepted, “objective” laws. How an external landscape became transmuted into striking images of his own life and exclusive experiences. Accordingly, Ekelund succeeded in converting melancholy and hopelessness into a calm breath, a sense of freedom far away from the hustle and bustle of everyday concerns that enabled him to create a new, almost magical language.

All that was certainly both enlightening and reputable, but for me it was like pouring water on a goose. I saw Grandpa's flowers, his astonishing garden, that was what Ekelund bestowed upon me through his poem. It was enough then, as well as now. My teacher's constant demand for "interpretations" disturbed me. However, I have to admit that it might not have been so inane, after all. Perhaps my annoyance was one reason to why many of the poems we read during my high school years have remained with me. If we had only read those poems without being forced to make those strained and complicated comments, I might just as well have forgotten them all. Now, for example, I can still remember Rainer Maria Rilke's poem about the panther in the Jardin des Plantes, which I was compelled to interpret, even if I considered that its meaning must have been crystal clear to each and every one who read it:

Sein Blick ist vom Vorübergehn der Stäbe

so müd geworden, daß er nichts mehr hält.

Ihm ist, als ob es tausend Stäbe gäbe

und hinter tausend Stäben keine Welt.

Der weiche Gang geschmeidig starker Schritte,

der sich im allerkleinsten Kreise dreht,

ist wie ein Tanz von Kraft um eine Mitte,

in der betäubt ein großer Wille steht.

His vision, from the constantly passing bars,

has grown so weary that it cannot hold

anything else. It seems to him there are

a thousand bars; and behind the bars, no world.

As he paces in cramped circles, over and over,

the movement of his powerful soft strides

is like a ritual dance around a center

in which a mighty will stands paralyzed.

(Stephen Mitchell)

Many years later I ended up in an apartment not far from the Parisian Jardin des Plantes and I often visited its zoo. Perhaps Rilke's poem was the reason to why I was attracted by it. Sometime, I brought with me a sketching pad, which I now have lost somewhere, drawing several of the animals. I remember the orangutans and the snow leopard, but cannot recall any panther.

A room at the Department of Nordic Languages at Lund University was decorated with a series of framed etchings reproducing the text of a poem by the Swedish poet Gunnar Ekelöf, his suggestive poem Höstsejd, Autumn Incantation:

Be quiet, be silent and wait.

Wait for the wild beast, wait for the foreboding that shall come.

Wait for the wonder, wait for the destruction that shall come,

when time has got insiped. Etc., etc …

When I got tired of the constant lecturing my eyes rested on the etchings and I had finally learned the entire poem by heart. That and an experience in Stockholm are the origins to the fact that Ekelöf since then has become a life companion.

In those days, I worked as a waiter on the trains between Malmö and Stockholm. This meant that after the lectures I hurried down to the station to catch a train. I had agreed with the Traffic Restaurants, TR, that it was OK if I boarded the train in Lund. If it was a large waggon the activities had already began. In those days there were still restaurant coaches on the trains, with white tablecloths, porcelain, a chef, a dishwasher and at least two uniformed waiters. On the other hand, if the carriage contained a so called two rooms and a kitchen, i.e. a cafeteria and a restaurant department separated by tiny kitchen area, I had to get started on my own, if not, as was often the case, a waitress had accompanied the coach from Malmö. My colleague in two rooms and a kitchen was almost always a young lady of my own age.

I was young at the time, perhaps as talkative as I am now, but at the same time quite shy and withdrawn. In Stockholm, if we did not spike, i.e. turned back on the same day, the train staff slept at Hotell Adlon on Vasagatan in Stockholm, where we were offered a beer and a sandwich when we arrived. The others used to go out together in the evening, but I generally excused myself by stating that I had to see my relatives. The tips were quite generous and enough for buying a ticket to the movies or a play. I often went the Dramaten, The Royal Dramatic Theatre and the Royal Swedish Opera. Particularily memorable was the impressive Jan Malmsjö as Hamlet, some of you might remember him as the demonic priest in Ingmar Bergman´s movie Fanny and Alexander. During several years I was able to imitate his “to be or not to be” monologue. How he came on to the scene carrying a sword with both hands and suddenly let it go so it with a loud bang, tremblingly stuck to the stage floor. In an intense, staccato-like manner he then performed the monologue while taking on and off a pair of glasses.

I do not really remember which operas I saw, but if I am not mistaken it was, among others, The Woman without a Shadow and The Knight of the Rose, though I still remember scenes from Ingmar Bergman's version of August Strindberg´s To Damascus and how I came to understood how theatrical, in the best sense of the word, Ingmar Bergman really was.

A few years later, during an unusually cold day between Christmas and New Year´s Eve, I travelled to Stockholm with two rooms and a kitchen. With me was an attractive waitress, somewhat older than me. She had thick chestnut hair and strange eyes, they were almost green, but shifted in grey and when she was looking at me it was as if her gaze went deep into me. She was witty and elusive, but nevertheless quite serious. Since it was a quiet day between two important celebrations the restaurant carriage was empty of guests most of the time. I didn't have to attend any lecture and thus travelled to Stockholm with the morning train.

For more than an hour we were stuck in the snow outside Norrköping. When we arrived at Stockholm´s Central Station she suggested that I accompany her to buy a pair of shoes. We went to several shops before she found for a pair of red wine coloured, high-heeled, velvet shoes. Impishly she wondered if I couldn't invite her to dinner, now when she was equipped with such elegant shoes. I invited her to Konstnärsbaren, The Artist´s Bar. My tips were far from being enough to pay the bill, so I had to add quite a lot from my savings. She fascinated me and I wanted to impress her by enacting a big spender, ordering a full, exclusive menu, fine wine to accompany it and cognac for the coffee.

The wind was hard and cold when we returned to the hotel. To avoid slipping with her high-heeled, velvet shoes, she had to cling firmly to me. We parted in the corridor outside our rooms. After a few minutes she knocked on my door and explained that she could not get the radio working. Our rooms were small and furnished in the same way. Strangely enough, the single rooms kept the radios screwed onto a shelf above the beds. It turned out that her radio functioned reasonably well and I remained.

On our way back to Malmö we talked for a long time. I explained that I wanted to see her again, though she said that it would be out of the question. When I wondered why, she replied:

– I have come to realize that you for some unfathomable reason are attracted by problems. I have problems. I'm a problem. You should be beware of me. I would not like to hurt you. You´re a nice boy and I beg you to avoid any further contact with me.

It was a bewildering answer. I never saw her again. Maybe she was only working temporarily at the Traffic Restaurants, possibly she had found out when I was working and avoided getting on the same train. Shy as I was in those days, I did not dare to ask about her at the Head Quarters. I wonder what happened to her. It was a long time ago. Then I was twenty-two, now I am sixty-four. It was certainly for the better that she left me there in Malmö. My life has been fortunate. I have not missed her at all, and up till now I have not been thinking about her, but back then she was for six months at the epicentre of my thoughts.

Two days after our meeting I was back in Stockholm. This time I had travelled alone in two rooms and a kitchen. It was snowing again. I had no desire to go to the cinema or the theatre. I felt miserable and worthless. In my head Ekelöf's poem was spinning, round and round: “Be quiet, be silent and wait. Wait for the wild beast, wait for the foreboding that shall come.”

Finally, I went out into the snowdrift, went to a bookstore and bought two books by Ekelöf. Since then I have often been browsing through Gunnar Ekelöf´s Poems, 1927 -1962.

I remember, I remember

and as I remember

I scent,

I presage my destiny, my life,

the one I have had and the one after this

So similar and nevertheless,

so different.

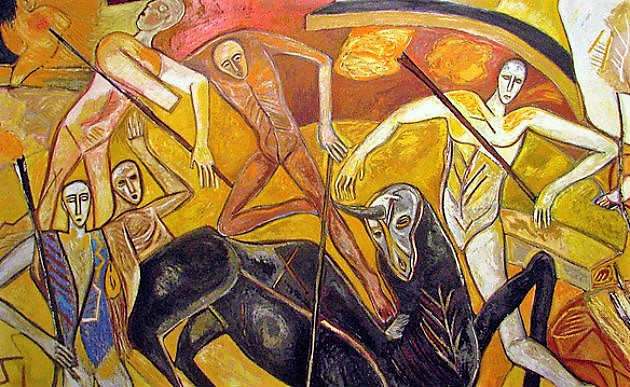

At the same time I had obtained Ekelöf's Rimbaud translations and that was when I found them on a shelf here in Rome that I began writing these lines. I had seen a painting Enzo Cucchi, La deriva del vaso, The Drift of the Vase. The title said nothing to me because the painting did not portray any vase at all, but a shipwreck that seems to be drifting within a sea of blazing lava – The Drunken Boat?

In spite of the fact that five amphoras are leaning against the broken mast, like those storing oil and wine which ancient Greeks and Romans loaded onto their ships, I understood that it was not a Mediterranean ship that Cucchi had depicted, but the Norwegian Oseberg ship, as it looked when it was found in 1904. Unlike most other Viking funeral ships, the Oseberg and Gokstad ships were not burned and they are now exhibited in the Viking Ship House at Bygdøy in Oslo. They are in their functionalist perfection among the most beautiful artefacts I have ever seen.

When I look at Cucchi's painting, it strikes me that his works of art are like the poems I remember from school. They can certainly be interpreted and explained, but I prefer to consider them in relation to my own life and experiences, that's how they speak to me. When I saw Cucchi's ship along with his painting Sospiro una onda, I Sigh a Wave, which also appears to represent a burning sea, though here it is not a ship that is thrown around in the waves of a nightly, flaming sea, but two skulls.

It is through these depictions of burning oceans that I came to associate Cucchi with Ekelöf and Rimbaud. The latter wrote in 1871, only sixteen years old, in Alexandrian verse the poem Le bateau ivre, The Drunken Boat. Not unlike the Cucchi paintings it displays a wild, glowing and rather insane story in which a boat tells us how it struggles with the sea. A feverish madness without any apparent anchorage the poem was born out of the boiling imagination of a teenager imbued with a profuse familiarity with fantastic worlds dreamt up by authors like Jules Verne, Edgar Allan Poe and Fenimore Cooper. Fantasising while leaning above contemporary illustrations with exotic landscapes and crazy savages it appears as if this boy in his rural backwater was particularly fascinated by pictures made by a certain Louis Figuier.

Rimbaud lets his drunken boat be tossed from Europe's rocky shores, with its dilapidated castles, far away to Florida's monster plants, panthers with human skin, the Arctic's frozen sea, and rotting swamps with Leviathan's carcass. The boat travels through the glare of white snow, green nights, a sea spotted by the sheen from silvery moons, glaciers, pearl beads, stormy seas coloured by glowing rainbows, in which decaying corpses are floating:

And from that time on I bathed in the Poem

of the Sea, star-infused and churned into milk,

devouring the green azures and pallid flotsam,

a dreaming drowned man sometimes goes down.

Strangely similar to Rimbaud´s imaginations, when he is not quietly lyrical as he may be from time to time, are the stanzas of the likewise impassioned and fanatic Isidore Lucien Ducasse, who under the pseudonym of Comte de Lautréamont at the age of twenty-three in 1869, at his own expense, published his verse drama Songs of Maldoror in which he in the guise of a blood-sucking monster with an overheated language attacks God and all imaginable moral. It is especially in some verses of his Une saison en enfer, A time in Hell, from 1873 that Rimbaud is reminiscent of Lautréamont. But it is highly unlikely that the young Rimbaud knew anything about the almost unknown French-Uruguayan Ducasse, who under mystical circumstances died in Paris as early as 1870.

It was Ekelöf's introduction to his Rimbaud translations that made me think of Enzo Cucchi and the Italian so-called Transavanguarde. I assume that Enzo Cucchi, who was a poet before he became a painter and became a member of the above-mentioned art fraction, was well acquainted with Arthur Rimbaud, who has long been a beacon for young poets, dreamers and anarchists.

On May the 15th 1871, Arthur Rimbaud sent a famous letter to Paul Demeny, a poet whose verses no one reads anymore and now is known only because he had the luck of receiving Rimbaud's manifesto. In this the sixteen-years old poet presents his ten years older colleague with a comprehensive lecture on Greek literature, Romanticism, modern French authors and literary criticism in general, while declaring that a poet "must be a seer [voyant], make oneself a seer." A writer, an artist, have to be a visionary and strive towards "the absolute". A poet's itinerary towards such a goal cannot be the same as step by step trail along a path. A true artist has to apply "a long prodigious, and rational disordination of all the senses." By experiencing "every form of love, of suffering, of madness, he consumes all the poison in him and keeps only their quintessences." Thus a poet may eventually arrive "at the unknown”, reach the depths of the unexpected.

In 1978, the art historian Bonito Oliva, professor of contemporary art at the Sapienza University in Rome, introduced the term Transavanguardia. According to Oliva much of the initial creative force of contemporary art had ended up in a kind of developmental thinking. Conservative artists, as well as radical Marxists, imagined that art was evolving chronologically from one stage to another. They assumed that that art constantly had to be renewed, or invented. An art concept is replaced by another and judged in accordance with its genre – cubism, futurism, surrealism, expressionism, abstract expressionism, superrealism, minimalism, etc., etc.

According to Oliva art should be released from such deterministic thinking. Great art is both time- and boundless. This does not prevent art from being political or goal-oriented, though inspiration ought be sought and found in nature, within the artist himself and perhaps primarily through an exploration of the vast ocean that has been created by art history, religion and poetry. Obtaining inspiration from different eras and places does not necessarily mean that the artist have to be a Christian, an African or a Renaissance humanist. Search and you will find. Search and you will become.

The term avant-garde indicates those who are in the lead of something. In the modern world a work of a great artist should be experimental and innovative. According to Bonito Oliva, this is a wrong way of considering creativity and art. Art is beyond time and space, while it paradoxically is enclosed by time and space. It is superior to the concept of the time-limited avant-garde, it is "trans" in the original Latin sense of the word transeo "transcend." Creation – beyond, above and within time and space. Around Bonito Oliva, a group of artists was formed, mainly engaged in figurative, symbolic art – Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, Nicola de Maria (the only abstract artist within the group) Mimmi Paladino and Enzo Cucchi.

Transavantguardism meant that art should have meaning and content, but it does not necessarily have to be interpreted. The viewer should be left free to experience a work of art in her/his own way, according to her/his abilities and experience, while art also should be rooted in the landscape, in myths and religion, in personal experiences and interpretations of existence.

Such a view of art and existence also characterized the views of the young Arthur Rimbaud. He was a cross-border character, an eternal seeker who never found what he was looking for, yet he was able to live in the present and find beauty there:

I am the traveller on the high road through the stunted woods; the roar of the sluices drowns the sound of my steps. I watch for a long time the melancholy golden wash of the sunset.

I might be the child left on the jetty washed out to see, the little farm boy following the lane whose crest touches the sky.

The paths are rough. The hillocks are covered with broom. The air is motionless. How far the birds and the springs are! It can only be the end of the world, ahead.

Rimbaud was the best student in the small town of Charleville´s high school; best in Latin, Greek, French, History, Geography. A teacher characterized him as one of these "perfect little monsters who win every race". But the little Arthur was restless. Time and time again he left home and lost himself in endless walks:

I went off with my hands in my torn coat pockets;

My overcoat too was becoming ideal;

I travelled beneath the sky, Muse! and I was your vassal;

Oh, dear me! What marvellous loves I dreamt of!

[…] My tavern was at the Sign of the Great Bear

– My stars in the sky rustled softly.

For the hiking Rimbaud, nature was animated. Even Flanders´s dreary mining landscape came alive and turned into music for the fifteen-year-old vagabond:

Grey crystal skies. A strange design of bridges, some straight, others curved, others again coming down at oblique angles to the first, and all these patterns repeating themselves in other windings of the canal that are lit up, but all of them so long and light that the banks, laden with domes, shrink and sink. Some of these bridges are still covered with hovels. Others bear masts, signals, fragile parapets. Minor chords cross each other and fade; ropes go up from the embankments. […] The water is grey and blue, wide as an arm of the sea. A ray of white light, falling from high in the sky, annihilates this make-believe.

The landscapes depicted by Enzo Cucchi are also enchanted. Like Rimbaud, Cucchi is an uneven artist, but when he is at his best he brings memories and wonders to life. Often it is mountains he depicts, with paths leading up to their peaks, which are populated by mysterious creatures. Mostly night or dusk prevail.

Occasionally, the mountains themselves are alive with eyes, hands and human forms. Yet they remain alien and sometimes threatening.

They can make me think of Kittelsen's Norwegian mountains, which obtain the shape of trolls and giants.

Or haystacks, which like ghosts move down the slopes.

Similarly, strange shadows and animals wander through Cucchi's landscape.

If the mountains might be lifeless themselves, they obtain life and presence through animals and people; camels, dogs, foxes, fishes.

The enchanted mountain landscapes of Cucchi make me remember what Andean peasants have told me. That mountains are endowed with different personalities. They own the animals, the crops, and the water that is born within them. Each mountain is unique. They can be alien to each other, or even enemies, though also family and close friends. There are female and male mountains, some are married, others alone and jealous. Some are dangerous and violent, others are friendly and generous.

The mountains talk to each other, either under or above the earth. They exchange gifts, communicating through storms and lightning or flowing water above and under them. Every animal that finds itself within their reign becomes the property of the mountains, even domestic animals that humans leave to graze on their slopes. Humans do not belong to the mountains, but the mountains have power over them.

In one of Cucchi´s paintings we see how a man carries a rooster under his arm while following a mountain path. He will probably sacrifice the animal to a mighty mountain spirit crouching high above on a mountain peak.

The spirit has an anthropomorphic aspect. It is neither animal nor human, but have frog-like features that also provide me with an impression of Andean mountain creatures. Rivers emerging in the highlands are guarded and protected by reptile-like creatures. Frogs and snakes are revered as holy creatures. They find themselves between different spheres; water and land. Such figures often occur among Cucchi´s visions of an animated nature.

The surrealist Max Ernst also created creatures that seemed to be a mixture between people, insects, reptiles, birds and plants. He called such a creature Loplop and several of his works have titles such as "Loplop presents ..." as if it is the nature itself and not the artist who has created the work of art.

Ernst and Rimbaud were blasphemous atheists. Christian symbols appear in their works, but they generally displayed contempt and scorn for Christianity. This is far from the views of Cucchi. His landscapes are often imbued with Christian piety. As in his drawing All Mountains are Saints. A typical Italian landscape with cross-crowned mountains, cypresses and a fish pond. His cypresses even wear halos and this makes me think of what one of my daughters once said: "There is not a metre of Italy that has not been touched and changed by humans."

By Cucchi, people are generally present. They change and create, but still seem to be an integrated part of nature. Like in his picture of a saintly figure who seems to grow out of a tree and a house, at the same time as he like the donors depicted in Italian churches seems to offer the same tree and house as gifts to God.

Nature lives by Cucchi, but at the same time it seems to be an ever-present threat. Like here where we see creative hands among the mountains, but they are overshadowed by a black cloud.

These clouds often occur in drawings and paintings by Cucchi. Occasionally caricature-like characters struggle with both clouds and stones.

Or the huge black stones/clouds overshadow nature and people in a manner that makes me remember how I, as a child, with meningitis and high fever came to imagine how huge, black boulders floated above me.

However, those stone clouds might not be so threatening after all. In one of his coal drawings, Cucchi has depicted a black stone between two apartment buildings. He called the drawing Panis Angelicus, The Angelic Bread, i.e. the name of the hostia, the bread of the Last Supper, Jesus's flesh indicating his divine presence among and within us humans.

Cucchi´s elliptic stones and clouds also remind me about cypresses, which also figure in a lot of his paintings. Cypresses are in Italy resurrection symbols, their spires point to the sky and Eternal Life. Though they were also for the ancient Mediterraneans the tree of Hades, the subterranean ruler and they were planted in cemeteries, a tradition that still is kept. Accordingly, cypresses belong to both heaven and earth. In many religions, perhaps even in Christianity, they are considered to be both phallic and vulvic and are thus mighty fertility symbols as well.

In the Dominican Republic I have often come across so-called thunderstones, elliptical black stones considered to have been left where lightning has struck. Sometimes, the shape itself is considered to be powerful and the stones do not necessarily have to be found in the earth. On vodun altars thunderstones are placed in bowls with oil, which eventually is used for lubrication to obtain either virile or female strengths. Thunderstones may also be immersed in water, which if consumed will also bring forth power and strength.

In popular Catholicism there is a connection between thunderstones and the Great Power of God, a life-giving force symbolized by a hand. At vodun altars you may find thunderstones resting between hands made out of cut-out paper, symbolizing the Great Power of God. Accordingly, I was surprised when I among Cucchi's drawings found a representation of a black stone/cloud hovering above a saintly figure, enclosed by a hand.

I also found a connection between black stones/clouds and death/rebirth in a Cucchi painting called Roma Morta, Dead Rome. In it we discern two black stones/clouds/wounds/cypresses rising from what might be catacombs indicated by a skull resting in one of the tunnel-like vaults. At the top left, a spidernet-like pattern may be glimpsed, which upon closer inspection turns out to be a map of Rome.

While confronted with this painting several associations appeared to me. Mainly something that my oldest daughter once said about Rome, namely that if you took away all the people from this city it would still be alive. It cannot be denied that wherever you go in Rome, history lives around you. The city is ancient and in several places, buildings have been erected above ruined temples, villas, churches and catacombs. Some of these ancient structures still remain more or less intact in the underworld.

So, even though Cucchi calls his painting The Dead Rome, the black, cypress-like shadows rising from the catacombs might be considered as signs of life. But, they may also imply the by many Romans feared miasma, i.e. the cold, moisture-laden mist that on hot summer days rises from cavities and underground water currents, feared because it is believed to be contaminated with mal aria, bad air.

It may seem like we have left Arthur Rimbaud behind, though this is not the case. As we saw in Cucchi´s Roma Morte, not only the landscape is animated, history also lives on and perhaps Cucchi, just like Rimbaud might exclaim:

I would have made, as a villain, the journey to the Holy Land; I have in my head all the roads of the Swabian plains, as well as views of Byzantium. And of the ramparts of Suleiman. The cult of the Virgin Mary, and compassion for the crucified one awaken in me among a thousand profane enchantment – I sit, stricken with leprosy, on potsherds and nettles at the foot of a wall ravaged by the sun – Later, as a mercenary, I should have bivouacked under the night skies of Germany.

Rimbaud seems, as the youngster he was, to have become intoxicated by his own brilliance, the ease and beauty with which he was able to express himself, by the power of his whims. For sure, his image of a drunken boat lost in a wondrous sea was quite accurate. Like the French-Uruguayan Ducasse, who in his writing threw all inhibitions overboard, the ingenious Rimbaud became completely unbridled amidst Paris´s absinthe-drinking bohemians.

Rimbaud´s drunkenness lasted for less than three years, and in the pale cast of thought Rimbaud finally became annoyed with his way of life and his authorship, maybe it had even been all the same. He had lived through and by his writing, they had been one and the same. Salvation through art and writing turned out to be a ridiculous chimera. Reality was nasty and depressing. Rimbaud wanted to leave all his dreams and writing behind and tackle life right on. He wanted to achieve peace and rest, but for that he needed money and the only solution Rimbaud could find, now when he disdained the arts, was to seek happiness and wealth in distant countries.

France was congested, Charleville stifling. Neverthelss, until he finally got stuck in Abyssinia and a vain pursuit for profit, Rimbaud did after every escape and adventure return to his mother´s house, He ended up there after his time in London, Brussels, Stuttgart, Stockholm, Vienna, Larnaca, Cairo, and Java. Charleville remained his safe anchorage. Yes, he even ended up there after his sojourn in Harar, the months before he met his death in a hospital in Marseille. Like his drunken boat that did not find its end as a shipwreck, but the poem ended up with the revelation that it probably was nothing more than a boy´s dream about adventures:

If there is one water in Europe I want it is the black cold pond where into the scented twilight a child squatting full of sadness launched a boat as fragile as a butterfly in May.

In Abyssinia it darkened above Rimbaud's path of life. He ended up in a dilapidated, lice-infected house in the Ethiopian walled town of Harar. Among its 30,000 wretched inhabitants he fought against recurring diseases while trying to earn an income while trading in coffee, ivory, gold, weapons and maybe even slaves, as well as trying pursue scientific endeavours. Rimbaud, who so often had written about roads opening towards an alluring future, was now walking down a path reminding of those who often appear in Cucchi's dark paintings, winding along between skulls and vultures.

Cucchi's skulls seem to have a life of their own, sometimes flooding the entire world. Occasionally it appears as they are showering down from the sky. In a drawing with the peculiar name Ikea they stream out of a hovering cottage. How can that drawing be interpreted? Cucchi seems to be just as obsessed with skulls as he is by elliptical, black stones. As in Vereschagin's depictions from a Far East where skulls are piled up in inhospitable wastelands.

While Rimbaud inertly tries to gain riches in an African backwoods a growing cancerous tumour is devouring his right knee. When he realizes he will die without proper medical care Rimbaud desperately tries to amass enough money to enable him to come back to his mother and leave her some savings.

This is where Enzo Cucchi finally encounters Rimbaud. In one of his paintings, within a black, brown and blue-red landscape Cucchi depicts a lonely, white-dressed Rimbaud, standing like a defiant loser in a distant land. The trader manqué seems to have a white bandage across his eyes. A sign of blindness, or a wet washcloth to relieve his fever? Probably not. Cucchi based his painting on a blurred photograph taken by Rimbaud himself. He stands by a coffee plantation just outside of Harar and what in Cucchi's painting seems to be a kind of bandage is probably a light reflex on Rimbaud's forehead. It is virtually impossible to distinguish any features in the face of the probably 35-years-old, but remarkably worn Rimbaud.

At Cucchi's painting, Rimbaud has the "white pyjamas without buttons" that had been described by an Italian visitor and which he also wears in the photograph. The difference is that Cucchi has painted a black wound on the right knee that, the one which through a malignant cancer soon would swell in a grotesque manner.

Cucchi's lonely Rimbaud reminds me of paintings by the Englishman Peter Doig, who also seem to have a preference for depicting lonely men in strange environments: like a snow-shoveller in Canada, or a man lost in a tropical swamp.

Rimbaud had reached the end of the road. He was eventually in severe pain during eleven days carried by sixteen men down to the port of Zeilah, from where a dhow took him across the sea to Aden and after another eleven days on a steamer Rimbaud finally arrived in Marseille, where his right leg was immediately amputated. His sister took care of him and brought him back to their mother in Charleville. Desperately, Rimbaud tried to walk with a leg prosthesis. He wanted to return to Harar, but his body was crammed with cancer metastases and after three months in Charleville he was back at the Marseille hospital, where he died. His sister draw a picture of her embittered brother lying on his death bed. With a bandaged hand Rimbaud stares with an empty gaze right in front of him.

I am searching among Enzo Cucchi's paintings and drawings to see if I can find any of them that do not give a timeless impression. A picture with a contemporary motif. To my surprise I could only find one. It represents a nocturnal train, in front of it hovers a white, female figure. She lacks legs and arms; maybe she is a sculpture. My schoolteacher would probably ask me for an interpretation.

OK – it is night, a yellow train, a beetle, a white female torso. Not at all easy to interpret all this. Why is the woman/sculpture hovering in front of a train? What is the green beetle doing there? Does it have anything to do with the woman? The insect is there because it is so utterly different from her? It will never be able to board the speeding train. Will it be crushed by it? Why not do as Ekelund? Take the exterior and turn it into something personal. One night at Adlon? The beetle is green like the woman's eyes. She's not quite complete because I never got to know her long enough to consider her as such. We met on a train. It disappears in the night. Like life, like memories which in the end become more and more obscured until they diminish in the distance.

I still remember Ekelöf's poem which was framed on the wall of the Department of Nordic Languages at Lund University. The last image said:

Be quiet, be silent and wait,

Breathless until dawn opens its eyes and breathless

until dusk closes its look.

Bernard, Oliver (1997) Arthur Rimbaud. Collected Poems. London: Penguin Classics. Bonito Oliva, Achille (2002) Transvanguardia. Arte & Dossier, No. 183. Firenze: Giunti. Borer, Alain (2006) Rimbaud; L´heure de la fuite. Paris; Gallimard. Lang, Walther K. (2007) "Sacre Visioni: L´opera giovanile de Enzo Cucchi" Arte & Dossier, No. 235. Lautreamont (1988) Maldoror and Poems. London: Penguin Classics. Mitchell, Stephen (1989) The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke. New York: Vintage White, Edmund (2008) Rimbaud: The Double Life of a Rebel. London; Atlantic Books.