INVENTION OF TRADITIONS: Waverley and Scottish Highland culture

Chilly rain pours down in Durham, but I am comfortable in my youngest daughter's home where I am relaxing while reading Walter Scott's Waverley. I ended up with that old novel since before I arrived here I spent some time in Edinburgh, where the railway station is named after Waverley, probably the only station in the world that is named after a novel.

It was not the first time I ended up in Scotland or Edinburgh. I came to Scotland in the summer of 1972 in the company of my youngest sister and her friend Inger from the Sophia Hospital in Stockholm, where they trained to become nurses. Inger brought her brother Ulf, amateur boxer from Gothenburg. Ulf and I got along well. While our sisters in the evenings spent a nice time on their own, we familiarized ourselves with the Scottish pub life. We had arrived in England after crossing an unusually stormy North Sea. The huge ferry had violently rocked up and down on mighty waves, while I and Ulf nauseous and fascinated sat by the restaurant's panoramic windows watching how the bow had disappeared under one surge after another.

From Newcastle we took the train up to Aberdeen, The Grey Granite City, where we stayed at a bed & breakfast owned by a nice, elderly couple. Mr. Gilmore was a Scottish patriot who frequently quoted his favourite poet Robert Burns and paid constant homage to Robert Bruce, who through the Battle of Bannockburn had beaten up "those pesky Englishmen."

Once a week, Mr. Gilmore brought with him his only golf club as he went to the King's Links´ golf course. According to Mr. Gilmore had "Goffe" been invented in Aberdeen, long before the "unfairly" famous golf course in St. Andrews had been founded. According to him it was at Kings Links that the world's oldest golf course had been established. Mr. Gilmore's golf club had by some local craftsman been made entirely out of wood, "just as it should be":

Irons are used for small details, like putts and the likes, according to me that is cheating. My ancestors used nothing else but wooden clubs and I am perfectly content mine, which furthermore is a beauty. Carrying around an entire bag with clubs is an invention by the wealthy moneybags of The Honourable Company of Edinburgh Golfers, who made their servants lug around with all that rubbish. It has become an abomination. Golf is a hearty Scottish sport created by and for ordinary Scots. Unfortunately, all those affluent capitalists turned a noble exercise into a sickening spectacle.

On Sundays, Mr. Gilmore dressed up in kilt and played the bagpipes in this garden. There is a Super 8 film depicting our excursions with Mr. Gilmore, but it was a long time since I last saw it. The likeable Mr. Gilmore made a lasting impression on me, he was a delightful example of Scottish nationalism. Mr. Gilmore´s benevolent enthusiasm came to characterize my approach to the Scottish people and their fascinating traditions, even though I have never been particularly fond of any exaggerated patriotism.

That visit to Aberdeen gave me a taste for more and a few years later I was back in Scotland this time in the company of my corridor mate Anki. We hitched a ride with a truck from London to Edinburgh and pitched our tent on a swampy campsite outside the city. During days the weather was decent, but every night the rain hurled down. Of course we quarrelled a lot, not surprising given the fact that Anki had a fierce temperament, our uncomfortable tent and earlier hardships in England when I was feverish with a cold, all combined with the chilly moisture. However, it did not prevent us from dressing up, leave the damp tent and spend days and evenings by visiting a wealth of activities during The Edinburgh Festival.

I had promised my father to write an article about in Norra Skåne and accordingly had a press card certifying that I was a temporary contributor to the local newspaper and it gave me and Anki free access to the press club and all activities. We watched everything from contemporary dance and experimental theatre, to Shakespeare, opera and ballet.

What has lingered in my memory was the Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo, with the Welsh troops´ saddle padded, long-horned goats, Scots with kilts and bagpipes and the emotional finale with a lone piper high up on the castle´s battlement, who in silhouette against the full moon played Amazing Grace. We had given up on our dank tent and spent the last night sleeping back and forth on various warm busses before we flew to Sweden - my first flight ever.

The night before I travelled to Durham, I remembered all this while I sat in a pub next to a blazing log fire, in front of a Haggis Tower and a pint of the excellent beer Innes and Gunn which obtains its special flavour after being stored in rum barrels. At a table sat a group of youngsters playing Scottish reels on pipe, violin and mandolin. Just as at the Café Greco in Rome, framed portraits of famous patrons from the past two centuries adorned the walls, among them were several of the city's famous authors - Arthur Conan Doyle, Robert Louis Stevenson, George MacDonald, J. M. Barrie, Hugh MacDiarmed, up until Irvine Welsh and J. K. Rowling. The pub was warm, cosy and filled with people. While massive, redheaded Scots and their pathetically ill-dressed companions in miniskirts came and went, I sat by my table for a long while, enjoying the convivial atmosphere, eating my haggis, drinking my Innes and Gunn and decided to finally read Waverley.

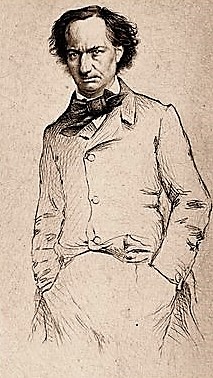

Actually, it is somewhat surprising that so many Scots speak warmly of Waverely. The novel is in some places unusually difficult to read, filled with a variety of allusions to historical figures and events. There are dialogues that turn out to be a chorus of different style exercises, where high and low English mixed with Latin, French and Gaelic, rich in allusions to ancient and contemporary writers and events. A compact style that often may be quite tiring and which has made several critics and writers pouring invectives on Walter Scott, who nevertheless gained respect from millions of readers all over the world, being praised by giants likes of Goethe, Balzac and Karl Marx. Charles Baudelaire, however, gave in his only novel Fanfarlo, written in 1847, thirty years after Waverley, a scathing critique of the Scottish bard.

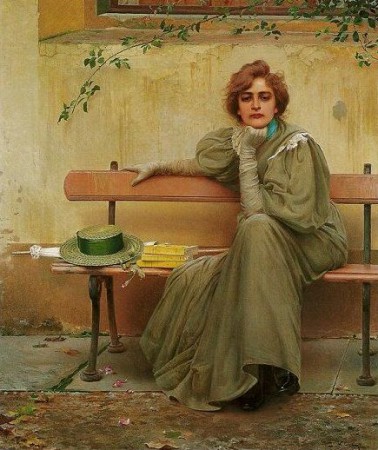

The protagonist of Fanfarlo is a reading and writing dandy and flaneur named Samuel Cramer, not unlike the twenty-six-year-old Baudelaire. Cramer is shadowing his youth love, Madame de Cosmelly, during her walks through the Luxembourg Gardens and approaches her by returning a novel she had left behind on a park bench. After having made the elegant lady remembering their shared memories and by exposing his immense literary interests Cramer manages to win her trust. However, he succumbs to what Baudelaire, true to the ironic attitude of his novel, characterizes as a common weakness of writers and critics, namely how they offend every person they encounter with ramblings about their own literary preferences, whether it happens to be a disinterested rag picker or entrepreneur, people generally uninterested in a writers´ literary opinions. In front of Madame de Cosmelly, Samuel Comer slashes the assumed talent of Walter Scott:

“Still, Madame!” said Samuel with a laugh. ”But what are you reading there?”

“A novel by Walter Scott.”

“Now I understand why you interrupt your reading so often! – Oh what a boring writer! – A dusty digger-up of chronicles! A dull accumulation of descriptions of bric-à-brac! – a pile of old things and all sorts of discarded bits and pieces: armour, dishes, furniture, Gothic inns and melodramatic castles, in which wander spring-loaded dummies, clad in jerkins and brightly coloured doublets. All well-known types, that no eighteen-year-old plagiarist will still want to touch in ten years´ time. Impossible chatelains and lovers utterly lacking in any modern significance – no truth as regards the heart, no philosophy as regards the emotions! What difference between him and our good French novelists, where passions and morals are always more important than the material description of objects! – What does it matter whether the chatelaine wears a ruff or panniers, or an Oudinet petticoat, provided she can sob or betray fittingly? Does the interest you much more because he carries in his waistcoat a dagger instead of a visiting card, and does a despot in a black coat cause you a less poetic terror than a tyrant clad in buffalo skin and iron?”

What apparently had irritated Baudelaire, in his guise of Samuel Cramer, was Scott´s alleged weakness for overloading his historical descriptions, though actually this is exactly the opposite to why Walter Scott was so appreciated at the time. He was then hailed as the historical novel's father. Instead of describing distant events from the perspective of royals and other celebrities, his historical depictions assumed the viewpoint of "ordinary people", describing their experiences and opinions; complicated events described within the context of carefully studied settings. Scott was praised for his ability to make history come alive, give it flesh and blood, something that inspired other writers of historical epics, like Victor Hugo, Dumas and Tolstoy.

Scott´s novels provide a sense of presence and trustworthiness. Admittedly, his novels tend to be populated by blond beauties and wild, passionate dark-haired ladies, who tend to be passed over by their more domesticand moderate rivals. However, if the reader ignores the occasional clichés, Scott´s stories are far from being as naive and simple-minded as they often have been considered to be. Even if Scott´s heroines are typified by their historical context they are far more multifaceted than they seem to be at a first encounter. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that Scott´s heroes generally appears as being hesitant and insecure, in spite of being attractive and masculine several of them suffer from a weak character making them quite easy prey to manipulations of stronger personalities.

Scott occasionally expressed contempt for his "colourless" heroes For example, he characterized Edward Waverley as "a sneaking piece of imbecility" and he felt that Waverley`s hero instead of the servile Rose had married the passionate Flora, she would:

have set him up upon the chimney piece as Count Borowlaski´s [more about him later on] wife used to did with him. I am a bad hand at depicting a hero, properly so called, and have an unfortunate propensity for the dubious characters of borderers, buccaneers, highland robbers […] My rouge always, in despite of me, turns out my hero.

The name "Waverley" alluded to the word wavering and Edward Waverley does not only waver between his allegiances to the English Government and his attraction to the revolting highland clans, but is also wavering in his romantic love for Flora and Rose.

Even if several persons close to him celebrated Walter Scott's generosity, openness and great kindness, many of them also spoke about his evasive and uncertain personality. He was not only a highly respected poet and novelist, but also a poseur, politician and an economically motivated schemer. It has, for example, been wildly speculated why Scott published his so called Waverley novels, i.e. those with a Scottish setting, anonymously. It took twelve years before he acknowledged the authorship of these, his most popular and internationally acclaimed novels, which until then had been issued under the name the Author of the Waverley Novels.

Explanations may be several - a sense of shame that a celebrated poet, lawyer, member of an old Scottish clan, historian, interpreter of venerable traditions and parliamentarian could waste his time by devoting himself to writing novels. At that time, novels were generally published as cheap booklets, primarily targeting romantically inclined ladies, or the sensationalist urge of literate members of the “lower classes”.

Perhaps Scott's desire for anonymity was mixed with an abnormally profound sensitivity to negative criticism, or a businessman's understanding that a certain amount of mystery tickles the interest of consumers. There was also a suspicion that if it was revealed that the immensely popular Waverley novels had been written by the successful author of lofty epics, they might be perceived as a cheap attempt to cash in on that fame. Scott earned money as his own publisher.

Maybe Scott needed a certain anonymity to let himself be inspired by a self-imposed role, a persona. While writing he entered into the role of an all-seeing, all-knowing author. He wrote at a high speed after devoting years to studies and preparation. His ever-changing role playing and occasional remoteness made Scott becoming labelled as The Great Unknown.

Several of Scott´s contemporaries have testified about how difficult it was to grasp Walter Scott´s individuality. He was a trusty companion, generous host, eloquent lawyer, mason and merry-maker, attracted to song and drink, though he could not dance due to a limp caused by polio in his childhood.

His good friend, author and the former shepherd James Hogg, who hailed Scott as "the greatest man in the world. What are kings and emperors compared with him? Dust and sand!" was nevertheless irritated by Scott's weakness for awards, titles, nobility, highly placed acquaintances and a ridiculous insistence on estate related etiquette during the parties and gatherings he organized. Famous artists such as Raeburn, Lawrence, Wilkie and Landseer complained about how difficult it was to catch Scott's character in their portraits despite the poet's distinctive looks, with a brow almost as high as Boris Karloff´s Frankenstein Monster. Maybe Scott was merely an insecure and oversensitive poseur, who constantly hid his inner feelings?

Yet, despite all these shortcomings, I cannot help but being fascinated by Scott's narrative powers and find myself involved in Waverley, discerning layers of interesting observations and ideas. Even in his writing, Scott was a chameleon, possibly this is not a deficiency, it actually makes him both distinctive and interesting. Through much of his debut novel Scott makes use of an ironic, narrative voice reminding me of Thackeray´s Barry Lyndon, both the novel and Kubrick's film. Scott keeps a certain distance from his story, which takes place against the background of the Stuart family's attempt to reclaim the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland. A struggle beginning when James II in 1671 converted to Catholicism and in 1689 was forced to abdicate and seek refuge in France, after his son-in-law, the Protestant William of Orange had invaded England.

William was supported by a disgruntled, English majority who disliked James´s Catholicism and his close contacts with Louis XIV of France. Until the Battle of Culloden James´s supporters, the Jacobites, most of whom lived in Ireland and Scotland, tried reinstate the Stuart dynasty on the throne. When James's son in 1715, after a failed uprising, gave up his hope of becoming English and Scottish king, the Jacobites transferred their support to his son, Charles Edward, called Bonnie Prince Charles or The Young Pretender. It is after his disembarkation on August 2, 1745 on the island of Eriskay among the Outer Hebrides, that the main story of Waverley unfolds.

The decisive battle of Culloden was fought during a hailstorm lashing the ill-disciplined Highlanders in the face, while they were subjected to a devastating firestorm from professional English troops. Almost half of Bonnie Prince Charles's troops had deserted before a battle they realized was going to be fought on a flat, swampy terrain. They were accustomed to attack their enemies from ambushes among their rocky homelands and were therefore reluctant to expose themselves on an open field, where well-aimed English canons would mow them down and they were easy targets for disciplined, targeted firing. The Highlanders lacked an effective artillery, their cavalry was insufficient and moreover, they were commanded by an inexperienced leader, who did not listen to their clan chiefs, but rather to his Irish and French advisers.

Singing their rowdy fighting songs and incited by their pipers the Highlanders rushed madly against the Redrocks´ methodical firing. The result was disastrous and followed by a ruthless repression during which the Scottish Highlands´ poor residents lost their land and were decimated by terror, hunger and distress, while their feudal lords betrayed them in their efforts to save their lands by allying themselves with the victorious authorities to improve agricultural profitability, streamlining sheep breeding, and safeguarding hunting grounds for the nobility, a policy which led to mass evictions of their tenants and their migration to the Lowlands and over the oceans to Canada and Australia.

Walter Scott reveals his narrative skills by keeping his hero off the decisive battles and preparations of the uprising. Admittedly, Edward Waverley meets with Bonnie Prince Charles and becomes involved with an influential clan chief and his fiery sister. The flamboyant clan chieftain Fergus Mac-Ivor Waverley was inspired by Scott's good friend Alexander Ranaldson MacDonell of Glengarry, whose stately Highland theatrics can be admired at Henry Raeburn's portrait of him in Edinburgh's impressive National Gallery.

Glengarry, as he was generally called, was often hailed by his friend Walter Scott, in spite of the fact that he was familiar with his vanity, violent temper and ruthless evictions of tenants:

This gentleman is a kind of Quixote in our age, having retained, in their full extent, the whole feelings of clanship, elsewhere so long abandoned. He seems to have lived a century to late, and to exist, in a state of complete law and order, like Glengarry of old, whose will was law to his sept, Warm-hearted, generous, friendly, he is beloved by those who know him, and his efforts are unceasing to show kindness to those of his clan who are disposed full to admit his pretension.

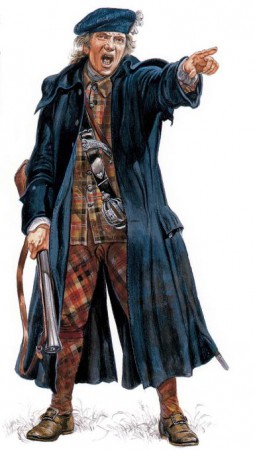

Within his overbearing personality Glengarry included some contemporary tendencies, mainly how the Highlands´ former feudal lords were ruthlessly enriching themselves at the expense of their faithful vassals. Despite this, several of them perceived themselves, like Glengarry, as genuine examples of traditional and benevolent tribal chieftains. Glengarry always wore the kilt, or patterned tartan trousers and like his ancestors he rarely journeyed without his tail; meaning that he dressed up his servants in kilts and armed them with broadswords and round shields, travelling in their company and with pipers, a blind minstrel and two tall youngsters who carried him across streams and rugged terrain.

After Culloden, the English made an effort to obliterate the so-called highland culture, including a total ban on kilts and tartan, a checkered woollen cloth assumed to be an attribute of “the Highland Spirit”. Nevertheless, kilts were allowed in the loyal Scottish regiments that had been established by clan chiefs and to which several young Scots were conscripted. The patriotic-minded Glengarry evaded the kilt ban by setting up a separate Scottish regiment, designing specific tartans and kilts for his recruits, this specific outfit can be admired on Raeburn´s portrait. Glengarry also created a cap, boat-shaped and foldable it was adorned with feathers and silk ribbons that hung down over the soldier´s neck. This so-called toorie is still worn by Scottish troops.

While he forcibly recruited young men to his regiment, Glengarry compelled most of his tenants to leave their land, to the end that these could be opened up, mainly as pastures for vast flocks of sheep, perhaps this endeavour was a part of Glengarry´s interest in fashion – tartan patterned plaids and kilts were made from Highland wool and manufactured by local weaving mills. During Glengarry´s reign over his feudatory, several ships with his evicted tenants left for Canada.

Walter Scott, who in Waverley describes Highlanders as some kind of noble savages, not much different from Fenimore Cooper´s Mohicans, and their Jacobite clan chiefs as highly educated nobles, several of them were actually Catholics and had actually been living in exile in France, Spain and Italy. Walter Scott was duly impressed by the ruthless Alexander MacDonell of Glengarry and his craze for folkish Highland manners. However, Scott´s poet colleague, the brilliant Robert Burns, saw through the Glengarry s folkish play acting and mocked the ridiculous nonsense acted out within exclusive Scottish societies where an increasingly wealthy nobility and bourgeoisie cavorted dressed up Highlanders during beer and whiskey drenched festivities, singing and celebrating a concocted Scottish culture, while they forcible emptied their large estates of people to make way for the expanding flocks of sheep and a ruthless deforestation of the remaining forests.

In the form of a nasty letter in verse from Beelzebub to the “Right Honourable President of the Right Honourable Highland Society” in which Burns, in the name of the Devil, sarcastically praises "Mr. Macdonald of Glengary" for so kindly taking care of the lands of their rightful owners, while providing them the opportunity to leave for Canada so they might find “that fantastic thing – Liberty”. Beelzebub offers Mr. Macdonald good advice on how best to discipline and torment the poor fellows remaining on his property, so that Beelzebub finally would be able to welcome the revered clan chieftain to his Hell. An excerpt from the letter provides a sample of the tone:

They’ll keep their stubborn Highlan spirit.

But smash them! crush them a’ to spails!

An’ rot the dyvors i’ the jails!

The young dogs, swinge them to the labour,

Let wark an’ hunger mak them sober!

The hizzies, if they’re oughtlins fausont,

Let them in Drury lane be lesson’d!

An’ if the wives, an’ dirty brats,

Come thiggan at your doors an’ yets,

Flaffan wi’ duds, an’ grey wi’ beese,

Frightan awa your deucks an’ geese;

Get out a horse-whip, or a jowler,

The langest thong, the fiercest growler,

An’ gar the tatter’d gipseys pack

Wi’ a’ their bastarts on their back!

Scott was more cautious and diplomatic than Burns, though his Waverley cannot be dismissed as propaganda for either Highland romanticism or Lowland capitalism. He clearly demonstrates that several tribal chiefs acted as mafia dons, demanding protection money from defenceless rural residents and that they did not hesitate to punish them and steal their cattle if they refused to pay. Although several clan chiefs were educated and sophisticated it did not hinder them from controlling gangs of hitmen and thugs. Likewise, Lowlanders and the English were not depicted as any saints either, the contempt for the poorer highland residents were endemic among many of them.

Edward Waverley´s vacillation was largely due to the fact can he could appreciate the values among both Highlanders and Lowlanders and could identify himself with individuals from both camps, something which made it difficult for him to choose sides in the bloody power struggle. However, he makes his selection by the end of the novel, when he marries Rose and turns his back on the passionate Highland beauty Flora. Everything indicates that Waverley finally ended up among Edinburgh's entrepreneurial elite, which flourished through international trade and the transformation of the Highlands.

The passion for Scottish culture took off in earnest when the English Government in 1782 lifted its ban on kilts and tartans, mainly under pressure from the influential weaving enterprise William Wilson & Sons, which since 1770 had delivered kilts to the military and now wished to increase their production by reaching general consumers as well. The basis for the Highland Renaissance had been established when James Macpherson in 1765 published The Works of Ossian, an anthology of assumedly ancient ballads, which Macpherson claimed to have found and written down in the Scottish Highlands. The anthology was made up of what had been preserved of an epic created by a Celtic bard in the 200's. Macpherson asserted that he had translated his ballads from Gaelic into English, but since they had been sung to him by informants in isolated villages it was hard to produce any ultimate proof of their existence and authenticity.

Macpherson´s “findings” took England and Scotland by storm, now they had their own Homer in Ossian, whose epic was translated into almost every European language and all over the continent became admired and plagiarized, although several legitimate doubts about their authenticity were presented by connoisseurs of Gaelic and Celtic narrative traditions, not the least by Walter Scott, though this did not hinder their significant impact on the creation of a unique Scottish culture.

Scottish patriots argued that an ancient Scottish culture had survived in the isolated highlands. As a matter of fact, the Highland culture and its ballads were more Irish than Scottish. Similarly, the Scottish plaids, which turned into tartans and kilts, also had an Irish origin. The Scottish Highlands had for thousands of years has been closer to Ireland and Norse influences than those of the eastern lowlands, which had maintained frequent contacts with England to the south, as well as with the European continent. This did not prevent wealthy, intellectual circles in cities like Edinburgh and Aberdeen to recreate a Scottish culture that they claimed to be more original and authentic than the one that could be traced to the rest of Britain and Ireland.

Great importance was given to a distinctive Highland dress, the patterned tartan and the kilt. As a matter of fact they were both remnants of a dress that once had been common among both Celts and Scandinavians; a large piece of fabric draped over the body and held in place by a broad leather belt and a large buckle, a fibula. In general it left one side of the upper body free, so warriors could swing their swords and battle-axes, while the rest of the mantle was draped over the other arm, depending on whether the bearer was right-, or left-handed.

The modern kilt, or as it is called felie beg, short kilt, was invented on the estate of the MacDonells in Glengarry, where a Quaker from Lancashire, Thomas Rawlinson, in 1727 established an iron smelter using wood from the forests of nearby Invergarry. MacDonells wanted the workers to wear the traditional long kilt, but Rawlinson found it to be cumbersome for the woodcutters and therefore introduced the short kilt, which basically was a skirt wrapped around the hips and held in place by a wide leather belt and a buckle. These felie begs were frequently patterned, though tartans patterned in accordance with clan belonging did not exist at this time.

The short kilt soon became popular and was used by the Scottish regiments, each of which wore specifically patterned tartans. In pictures of Scottish prisoners of war made by the Swiss artist David Morier, who accompanied the Duke of Cumberland during his battles against Highland insurgents, we find that they wore short kilts or tartan patterned trousers.

That different clans wore specific tartans is largely an invention by the brothers John Carter and Charles Manning Allen, who called themselves Sobieski Stuart and claimed to be the only surviving descendants of the in reality extinct Stuart family. The myth of clan tartans were in circulation even before the brothers Allen made a big deal of it and in Waverley, written in 1814, Scott mentions:

By the light which the fire afforded Waverley could discover that his attendants were not of the clan of Ivor, for Fergus was particularly strict in requiring from his followers that they should wear the tartan striped in the mode peculiar to their race; a mark of distinction anciently general through the Highlands, and still maintained by those Chiefs who were proud of their lineage or jealous of their separate and exclusive authority.

The Allen brothers supported their imaginary mapping of various Clan Tartans through various counterfeit manuscripts and they came to have a huge importance for the development of a history of the kilt. A decisive factor was their assurance that they had found an old manuscript verifying that different tartan patterns had been in use by specific Highland clans already during the Middle Ages. In 1842, the Allen brothers published a magnificent volume illustrated with unique colour pictures, allegedly reproducing a now lost manuscript, Vestiarium Scoticum, which they had found in 1827 and claimed having been compiled in 1571 and then based on an even older manuscript. The author of the Vestiarium Scoticum had been a certain Bishop John Leslie, confidante of Mary Stuart. Two years later, the brothers published an even more lavish edition, now completed with meticulous records of their research in the Highlands and in different European book collections, The Costume of the Clans. Everything was fakes and fantasies, though Scottish weavers and tailors gratefully accepted it all and soon spread the Allen brothers´ discoveries through pattern books and scientific papers, while they produced an extensive selection of imaginative Clan Tartans. Meanwhile, the Allen brothers continued to propagate their sensational finds and dressed in eincrasingly amazing Highland costumes.

Kilts and patterned tartans are now widely accepted as ancient pillars of Scottish culture. In Mel Gibson's costume epic Braveheart from 1995, for example, we witness how virile Scots rush forward in kilts and with blue-painted faces. The film's hero, the medieval nobleman William Wallace, was not as the movie asserts son of a farmer and prabaly fought on horseback dressed in hauberk, like a medieval knight, as did several of his warriors. The peasants and shepherds who participated in the fighting probably wore trousers and not kilts.

Gibson probably got his idea about blue war paint from descriptions of the ancient Picts, who according to Latin authors lived in Scotland, which by the Romans was called Caledonia. Picti, mean ”painted” and the Roman historian Eumenius mentioned in 297 the Picts in few sentences, indicating that they were “blue”. It was probably for the same reason that the Arab Ibn Faladin, who in 921 met Swedish Vikings on the Volga, described how they from "fingers to the neck" were covered with dark-green images of trees and various symbols. Probably they were rather dark blue tattoos, which were created by the use of dyes made from a specific wood ash. That the Picts were tattooed and not painted seems to be confirmed by another Roman source – the historian Herodianus (170 - 240), who mentioned that the negotiators who came down from the countries north of the Hadrian's Wall, which constituted the boundary between the Roman Brittania and Caledonia, were naked, except for iron bands carried around waist and neck and that they were tattooed from head to foot.

Like so many other depictions and descriptions of Scottish Highland culture and costumes Gibson's imagery is built on at least as many unproven legends as historical realities. However, myths easily turn into reality, as evidenced by the variety of clan-related kilts exposed in so many storefronts in Edinburgh, or the "genuinely Swedish culture" that Sweden Democrats' propaganda alludes to, as well as the genuine, national, cultural traits claimed by so many other national parties, like Sinn Féin in Ireland, National Front in France, True Finns in Finland, Lega Nord in Italy, Jobbik in Hungary, LDPR in Russia, etc., etc.

It cannot be denied that such legends and myths, or exciting literature like Waverley can be stimulating and lead to new discoveries. For example, I winced when I found that Scott wrote that Count Borowlaski´s wife used to put him on the mantelpiece. A strange statement, but since I found myself on a train bound for Durham when I read it I remembered that Józef Boruwłaski was a dwarf who died in Durham and when I ended up in Durham, I visited with my daughter, Durham´s Town Hall where there is a natural seized statue of Boruwłaski and a glass cabinet displays his suit, chair, walking cane, violin, hat box and shoes.

Count Boruwłaski was at the age of thirty just a meter high and he died in Durham in 1837 at the then estimable age of 97 years. He was then a respected citizen and was buried Durham´s famous cathedral. Boruwłaski was born in Poland and had been a friend of kings and emperors in Poland, Austria, France and England. He had two beautiful daughters and had been married to a celebrated beauty. He was a well-read and a stimulating converser, a talented guitarist and violinist, with an exciting life behind him, which he related in three autobiographies. And the mantelpiece? It was actually not a mantelpiece, but a high closet that Count Boruwłaski himself told his full-grown and temperamental wife placed him when she was angry at him.

And Bonnie Prince Charles? What happened to him after the disastrous Battle of Culloden? He fled across the Scottish moors, constantly harassed by English troops, but no one betrayed him for the 30,000 pounds promised to the one who could provide information of his whereabouts. Finally, Charles succeeded, disguised as a maid-servant to Flora MacDonald, with a small boat escape from the island of Skye to a waiting French frigate. Flora's grandson was later killed in a duel with the fiery and infamous Alexander Ranaldson MacDonell of Glengarry.

Bonnie Prince Charles continued to dream of eventually becoming an English king, but became increasingly alcoholised and although he went from woman to woman he did not generate a heir and died in Rome as a pathetic parody of his former and handsome persona Bonnie Prince Charles.

In a short novel, Castrates, the Swedish author Sven Delblanc recounts a nightly séance in the Stuart dynasty´s crumbling palace in Rome. The Swedish king Gustaf III, his favorite Gustaf Mauritz Armfelt, the aged Bonnie Prince Charles and the famous castrate singer Marchesi conjure up spirits and soon Marchesi´s even more illustrious colleague Farinelli appears, but he turns out to be a careworn, pathetic spirit. The dilapidated palace is populated with a great variety of ghosts and spirits, even Gustaf III and Charles Stuart appear as pathetic relics from a time that soon will go to the grave, being just as sterile as the two castrate singers.

Delblanc´s depiction of how the drunken and prematurely aged Bonnie Prince Charles receives his guests by the entrance to Palazzo Muti is probably not far from reality:

Surrounded by servants, Charles Edward came reeling down the stairs, intoxicated with sleep or inflamed from other causes, bent with age, intensely red in the face with his clothes in disarray, flapping like a moulting crane losing its plumage. On the blue bodice there was an order cluster, but the naked legs in the kilt´s red tartan were scraggy with age, the Order of the Garter had slithered down to his tarsus. […] White beard stubble on bloated cheeks, efflorescent with drink, deranged in dress, he finally stood on the bottom step, he who by some was called Charles Edward Stuart, Knight of St. George …

Of course, after returning to Rome I rode on my bike to the Palazzo Muti, located in the city centre. In vain I searched for one of the marble slabs which usually are found on ancient Roman houses informing that they once had been inhabited by some famous person. While I stood in front of the palace and I noticed the name Balestra above the entrance gate I became increasingly uncertain if this really could be the famed Stuart palace.

While I stood there in the drizzle an older, erect gentleman came out of the house. He made an eccentric impression with a Borsalino, an elegant coat in beige cashmere and a moustache with upturned tips. While he opened his umbrella, I went up to him and wondered if this was the Palazzo Muti. While he interested inspected me through his horn-rimmed glasses, he kindly replied:

- Of course it is!

- But, it says “Balestra” above the gate.

- Oh, that is nothing you should worry about. By the way, are you a Scot?

- No, I am Swedish. How come?

- It is only Americans and Scots who tend to ask if this is really the famous Palazzo Muti. For you are curious if this is the Stuart´s palace, da vero?

- Yes, though I assumed it would be a sign somewhere.

He laughed:

- Everyone assumes so and there is certainly a sign. It is only that you have come on the wrong day, the door is closed on Saturdays and Sundays. Come, you I will show you.

Politely he opened the heavy gate, let me step inside and on the wall of the doorway there was actually a marble plate:

In this palace lived Duke Henry, who then was Cardinal of York and as the last surviving son of James III of England had taken the name Henry IX and with him in 1807 the Stuart dynasty was quenched.

Henry Benedict Stuart was Bonnie Prince Charles´s homosexual and accordingly childless younger brother and like Charles he had been born and died in the same palace, the equally childless Charles had then been dead for nineteen years.

I continued my bike ride to the Vatican where I in St. Peter's Basilica for a minute stood in front of the Stuarts´ elegant tomb monument, created by Canova and paid for by the English King George III. Henry Benedict Stuart would certainly have appreciated the beautiful, naked and wing adorned youths, Eros and Thanatos, who with extinguished torches bow their heads while standing on either side of the entrance to a mausoleum above which is written in Latin: "Blessed are those who die in the Lord." During World War II, the Stuarts sarcophagus in the basilica´s crypt was restored at the expense of The Queen Mother, also as an excuse for the misery that the British had inflicted the Highlands after the battle of Culloden.

Baudelaire, Charles (2001) The Prose Poems and La Fanfarlo. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Crawford, Thomas (1982) Walter Scott. Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press. Burns, Robert (1993) Selected Poems. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics. Delblanc, Sven (1979) The Castratri: A Romantic Tale. Ann Arbor MI: Karoma Publishers. Hogg, James (2010) Familiar Anecdotes of Sir Walter Scott. Charleston SC: Nabu Press. Hudson, Benjamin (2014) The Picts. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. Hutton, Richard H. (1878) "Sir Walter Scott," in Hayden, John O. (ed.) (1970) Walter Scott: The Critical Heritage. London and New York: Routledge. Prebble, John (1973) The Highland Clearences. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. Prebble, John (1974) Culloden. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. Prebble, John (2000) The King´s Jaunt. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd. Scott, Walter (2011) Waverley. London: Penguin Classics. Trevor-Roper, Hugh (1987) “The Invention of Tradition: The Highland Tradition of Scotland,” in Hobsbawm, Eric and Terence Ranger (eds.) The Invention of Tradition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Webb, Simon (2008) In Search of the Little Count: Joseph Boruwlaski, Durham Celebrity. Durham.