LA SERENISSIMA: Venice as woman, dream and death

The train to Venice travels over water. We are approaching the enchanted city a week before Christmas, on both sides of the wagon everything is grey. Grey sky, grey water, a glimpse of a wooded island, also grey but of a darker shade.

Forty-two years ago I travelled along the same railway bridge, but then it had been high summer and quite hot. When we stepped off the train I and Claes found ourselves in great spirits and hurried to a hotel in the backstreets. The good-looking, young lady who prepared the room for us told us we were handsome ragazzi nordici and gave each of us a kiss, then we sat outside a small trattoria, watching the pretty girls we assumed were Venetians, drank wine, ate pasta and shouted: "We live here!"

I had been in the city before and have since returned several times. Always amazed by what the Hungarian writer Antal Szerb described as:

the essential Veniceness of Venice: the water between the houses, the gondolas, the lagoon, and the pink-brick serenity of the city.

Venice was, is and will remain a hallucination, a castle in the air where she with her palaces, streets, and bridges seems to float on the lagoon's tranquil waters. Many of the short stories and novels set in the city emerge as dream books - Death in Venice, Don´t Look Now or The Comfort of Strangers.

Charles Dickens visited the town in 1845, four years before the railway bridge was finished, depicting his stay as a dream/hallucination. He and his family arrived in gondola and having dozed off Dickens found that it had become night and he was suddenly inside the city:

Before I knew by what, or how, I found that we were gliding up a street—a phantom street; the houses rising on both sides, from the water, and the black boat gliding on beneath their windows. Lights were shining from some of these casements, plumbing the depth of the black stream with their reflected rays, but all was profoundly silent.

All throughout his story Dickens stuck to the dream illusion and did not mention any place by name while he wrote about his confusing visits to churches, palaces and dungeons. He lingers on the otherworldly beauty of the town, but does not fail to point out its often sinister dilapidation and the constant presence of water:

But close about the quays and churches, palaces and prisons sucking at their walls, and welling up into the secret places of the town: crept the water always. Noiseless and watchful: coiled round and round it, in its many folds, like an old serpent: waiting for the time, I thought, when people should look down into its depths for any stone of the old city that had claimed to be its mistress.

The stories I mentioned above are all some kind of nightmares, where the city's decay, labyrinthine alleys and stinking canals evaporate death and moral decay, combined with a hint of sensuality: dark urges, forbidden temptations. Venice seems to generate desire and death, as in Henry James novel The Wings of the Dove with its shades of loneliness and recurring apathy, in tune with a cynical and partially hidden message telling us that when it comes to money, sex, love and death, most of us are prepared to accept far more than we are willing to admit.

Not for nothing was Venice Casanova's birthplace and hometown of the father of modern pornography - Pietro Aretino, Michelangelo´s and Titian's friend and supporter, who occasionally earned his living through various forms of extortion. Nowadays we find Tinto Brass in the city, creator of a number of more or less artistic, pornographic movies and married to the daughter of Giuseppe Cipriani, founder of Harry's Bar, which through the decades has been a Venetian haunt for men like Toscanini, Chaplin, Hemingway, Hitchcock, Capote, Orson Welles, Onassis and Woody Allen, as well as a host of luminary scouting tourists.

The city is often likened to a woman and called La Serenissima, The Most Serene, but can also be described as erratic and nervous. Henry James wrote in 1882:

It is by living there from day to day that you feel the fullness of her charm; that you invite her exquisite influence to sink into your spirit. The creature varies like a nervous woman, whom you know only when you know all the aspects of her beauty. She has high spirits or low, she is pale or red, grey or pink, cold or warm, fresh or wan, according to the weather or the hour. She is always interesting and almost always sad; but she has a thousand occasional graces and is always liable to happy accidents.

Rarely is Venice likened to a matron, or faithful wife. In masculine fantasies which dominate depictions of Venice the city is mainly associated with attractive, but wanton mistresses, something that may possibly have to do with the city's reputation as a den of sin and prostitution.

Venice´s voluptuous, indolent courtesans were depicted on masterpieces by Titian, Giorgione and Veronese. Already in 1358 Il Gran Consiglio di Venezia, the city government, declared that prostitution is "absolutely necessary for the world" and introduced state-sponsored brothels in several major Italian cities. Legal prostitution was one of Venice's attractions when it was a world metropolis, the centre of trade and shipping.

Numbers, of course, are difficult to find. The common perception that a tenth of the city's female population, during a large part of the Republic's existence, where prostitutes are probably exaggerated, but women's social position was never laudable and their political influence non-existent. As a counterweight to the widespread prostitution can it probably be mentioned that during the sixteenth century an estimated 60 percent of the Venetian women from nobility and high bourgeoisie were nuns. Several of them against their will, forced into monastic orders by parents who had been unable to find suitable husbands for them, not been able to pay dowry, or for blunders that had made the ladies unattractive in the marriage market.

The link between femininity and Venice was so great that the city could be seen as a competitor to other women, like the wife of one of La Serenissima´s greatest admirers - John Ruskin, in his time a very influential art critic, artist, patron, poet and writer, who bestowed Venice a passion bordering on unconditional love. His young, exceptionally attractive and fun-loving wife, Euphemia "Effie" Gray, devoted herself to an intense social life, flirting and dancing with the Austrian officers, who her husband feared would demolish the palaces and churches he carefully documented with camera and pencil.

In his comprehensive work The Stones of Venice, published in three volumes from 1851 to 1853, Ruskin describes in great detail no less than eighty Venetian churches and in them traces what he considered to be of paramount importance for a true human architecture, namely “sacrifice, truth, power, beauty, life, memory and obedience.” Buildings, enclosing different lives and activities, reflect humanity's hope and aspiration, thus they also have, at least according to Ruskin, a life of their own and a very specific character.

Venice lives, while its stones speak to us, but it is a tired, ancient city constantly threatened by death. In Ruskin's time it was also a conquered and humiliated city, which in 1849 had surrendered to the Austrians, after months of siege, starvation and a relentless bombardment from land and air.

Venice was the first city in world history to be bombed from the air. The Austrian army let balloons drive in over the city, dropping time bombs. Targets were hit at random, most of the bombs were cluster devices intended to randomly kill and injure as many people as possible, creating terror among panicking Venetians. Ruskin wrote about the destruction of the city's buildings and a strong sense of resignation among the population, but what he was particularly fascinated by was the slow progress of threatening sea, which made the crumbling city inevitably sink into the lagoon's green waters. Like a beautiful woman engulfed by age and listlessness.

Ruskin had initially intended to write only about architecture. Venice is a thoroughly human creation, but Ruskin's description of Venice's buildings developed into so much more. As an exquisite, but undisciplined, stylist he had a tendency to lose himself in a variety of topics, something that for reader may result in both fascination and desperation:

[One] reason why Ruskin is hard to read is his inability to concentrate. This was part of his genius. In his mind, as in the eye of an impressionist painter, everything was more or less reflected in everything else; and when he tries too hard to keep his mind in a single track [...] some of its beautiful colour is lost. Still, it must be admitted that after the age of about thirty his inability to stick to the point becomes rather frustrating, and in his later writings, where literally every sentence starts a new train of thought he reduces his reader to a kind of hysterical despair.

Accordingly it is not surprising that Ruskin was fascinated by Venice with its proximity to the constantly changing water, which makes light and colour shimmer and change from minute to minute.

One of the concerns that Ruskin expressed in his Stones of Venice was that the city was being corrupted, slowly but unrelenting. An abandonment of the true Christian faith had compromised its cultural achievements and the entire society had been damaged. This made the city´s sad fate a warning to an increasingly perverted England.

According to Ruskin the seeds of destruction had been sown when Venice was at the height of its blossoming. Splendid Renaissance artists had in pagan worship of their ability to produce dazzling beauty arrogantly turned their backs on God, and thus had the moral and spiritual health of a once vital and vigorous society been destroyed by pride and pleasure hunting. A voluptuous way of living had led to the creation of an indolent upper class, while able workers, who had built the churches and harnessed the water, were becoming marginalized and a host of idle vagrants was created.

Ruskin described how staircases and colonnades were littered by droves of idle men, laying "like lizards in the sun", while their dirty offspring was running around aimlessly; shouting themselves hoarse, swearing, stealing, begging, fighting and playing for pennies by "clashing their bruised centesimi upon the marble ledges of the church porch. And the images of Christ and His angels look down upon it continually".

Venice's history and decline made Ruskin reflect on the present state of human society:

We want one man to be always thinking, and another to be always working, and we call one a gentleman, and the other an operative; whereas the workman ought often to be thinking, and the thinker often to be working, and both should be gentlemen, in the best sense. As it is, we make both ungentle, the one envying, the other despising, his brother; and the mass of society is made up of morbid thinkers and miserable workers. Now it is only by labour that thought can be made healthy, and only by thought that labour can be made happy, and the two cannot be separated with impunity.

It was light and water that had seduced the by Ruskin so greatly admired Renaissance artists:

The Assumption [in the Frari Basilica] is a noble picture because Titian believed in the Madonna. But he did not paint it to make anyone else believe in her. He painted it because he enjoyed rich masses of red and blue, and faces flushed with sunlight.

Of course this is a generalization, but it cannot be denied that the Venetian Renaissance masters were fascinated by exuberance, colour and light. Titian´s Madonna is masterly achieved, with striking colour harmonies; her mantle in various shades of red and its billowing sash in a saturated blue with dark shadows, against a background of gold and yellow sunshine, all created to be savoured from a distance.

A similar, generous brilliance is evident in Veronese's art, especially if you have the enjoyment of admiring his paintings in all their dazzling freshness, liberated from the dirt and grime that overtime have disfigured so many oil paintings. Like the immense Marriage at Cana in the Louvre, with its turbulent and asymmetric crowd of luxuriously dressed aristocratic figures in an extravagant setting, filled with imaginative and exciting details. Unfortunately a lot of museum visitors probably miss the opportunity to admire this masterpiece. It covers the wall opposite the Mona Lisa and many are certainly too eager to break through the throng to watch her well-known face, hindering them from paying attention to the extravaganza behind their backs.

It is striking that Veronese did not bother too much about creating a heartfelt devotional image. When the Inquisition summoned him for an explanation as to why he had filled his painting The Feast in the House of Levi with irrelevant details like "buffoons, drunken Germans, dwarfs and other such scurrilities" Veronese responded:

- We painters use the same license as poets and madmen, and I represented those halberdiers, the one drinking, the other eating at the foot of the stairs, but both ready to do their duty, because it seemed to me suitable and possible that the master of the house, who as I have been told was rich and magnificent, would have such servants.

When the Inquisitor wanted to know if someone had asked him to paint “Germans, buffoons, and other similar figures” Veronese answered:

- No, but I was commissioned to adorn it as I thought proper; now it [the canvas] is very large and can contain many figures.

But it would be wrong to regard the Venetian masters´ appreciation of colour, light, luxury and extravagance as a lack of sincerity, piety and compassion. Consider the splendour loving Tiepolo's representation of Christ's road to Calvary in Venice's St. Alvise church, where Jesus has fallen to the ground under his heavy cross, in the middle of a swirling cloud of colourfully dressed soldiers, grieving people and robbers sentenced to death. The display of colours, the elaborate composition and vitality of the movements around him make Jesus' suffering expression even more prominent and pervasive. The viewer cannot avoid identifying with him.

The colours of Tintoretto, Titian and Veronese darkened when the masters grew older and apparently opened themselves further to the mystery of faith; its deeper, darker aspects. In the aging Veronese's representation of Jesus' agony in Gethsemane the colours and vigorous brush strokes have not lost any of their force and decorative effect, but they have become endowed with a deeper passion than before. The weary Jesus collapses in the arms of a comforting angel, while a heavenly light is cutting through the surroundings dim, smoke blue colour.

According to Ruskin had a strong Christian faith inspired the Venetians during their endeavour to master the marshy islands and through hard work transform them into a magical kingdom of gold sparkling mosaics, magnificent churches and palaces. However, decadence had slipped in and tarnished the perfection and the cause for this tragic state of affairs was mainly the same element that made the miracle possible - water.

In few places is the link between water and art as evident as in Venice. The greenish water of the lagoon is a powerful source of inspiration, but also a carrier of progressive decay. The water's transformative power unites passion and death; in architecture, in art, and especially in music. Listen to Vivaldi's fresh sounds and you will discern the sound of water and weather changes, while the Swedish poet Thomas Tranströmer reminds us that it was in Venice that Wagner died. The month before the composer's death, he was visited by his father-in-law, Franz Liszt, who on the piano played a heavy, slow-advancing tune.

Wagner was seriously ill, he suffered from excruciating chest pain. Liszt was not present when Wagner died and his failing health prevented him from attending the funeral in Bayreuth. Liszt suffered from asthma, insomnia and heart problems and had declared: "I carry in my heart a deep sadness that occasionally needs to break through in notes."

It was when Liszt was told that the deceased Wagner by gondola had been taken along the Grand Canal from Palazzo Vendramin to the Santa Lucia railway station, named the piano piece he had played for the dying Wagner La lugubre gondola, The Sorrow Gondola. In a poem with the same name Thomas Tranströmer brings us to Wagner's death bed and invites us to listen to Liszt playing The Sorrow Gondola, finding inspiration, as well as the ominous presence of death, in Venice´s rising water:

Two old men, father-and son-in-law, Liszt and Wagner, are staying by the Grand Canal

together with the restless woman who is married to King Midas,

he who changes everything he touches to Wagner.

The ocean's green cold pushes up through the palazzo floors.

Wagner is marked, his famous Punchinello profile looks more tired than before,

his face a white flag. [...]

Liszt has written down some chords so heavy, they ought to be sent off

to the mineralological institute in Padua for analysis. [...]

Beside the son-in-law, who's a man of the times, Liszt is a moth-eaten grand seigneur.

It's a disguise.

The deep, that tries on and rejects different masks, has chosen this one just for him—

the deep that wants to enter people without ever showing its face. [...]

When Liszt plays tonight he holds the sea-pedal pressed down

so the ocean's green force rises up through the floor and flows together with all the

stone in the building. [...]

The night before he died, Wagner sat by the piano and played the Rhine Maidens´ Lament from the finale of his opera Das Rheingold. On the bedside table was Friedrich de la Motte Fouque´s novel about the water spirit Undine. Both the evening´s music selection and the bedside reading matter bring us back to Venice´s watery feminine essence.

The Rhine Maidens´ surging lament over the loss of their gold builds up towards a violent crescendo, a warning about the water´s destructive force. The sensual, aquatic Rhine Maidens, naked and with loosened hair, are a symbol of feminine allure, manifested through the water´s capricious impermanence. Music scholar Lawrence Kramer has observed that Wagner occasionally replaced the fire of passion with the continuously swirling, endless rhythmic water. Sexuality becomes transformed from heat to coolness, life itself underwent a metamorphosis from fire to water, as a matter of fact does Wagner´s mighty opera suite end with the world being purified through water when the Rhine floods the castle of the Gibichungs, making it possible for the Rhine Maidens to retrieve their coveted ring. Nudity, water and hair had become the epitome of sexual allure.

An important, symbolic feature of water living, feminine creatures is their long, swirling hair. In her study The Power of Women's Hair in the Victorian Imagination Elisabeth Gitter argues that because the fashion of the time dictated that hair and face were the only parts of a women which could be exposed, the masculine imagination provided women´s hair with an "excessive" sexual allure. Furthermore, freely flowing hair was associated with water. The naked mermaid with her billowing thick wavy hair became in European art a symbol of female, uninhibited sexuality - a menacing attraction. Virtually every aquatic fable creature was in folklore considered to be both enticing and deadly. As Thackeray describes them in his Vanity Fair:

They look pretty enough when they sit upon a rock, twanging their harps and combing their hair, and sing, and beckon to you to come and hold the looking-glass; but when they sink into their native element, depend on it, those mermaids are about no good, and we had best not examine the fiendish marine cannibals, reveling and feasting on their wretched pickled victims.

The most fearsome female water creature of them all was Medusa, whose horrible hair of living, sinuous snakes by some psychotherapists has been interpreted as a symbol of male fear of female genitalia. John Ruskin´s divorce from the lovely Effie Grey caused a lot of speculation, even during his own lifetime. Ruskin had somewhat cryptically explained that the divorce was caused by the fact that he had imagined women to be quite different until Effie had revealed herself to him. Effie explained in a letter to her father why she was still a virgin:

He [Ruskin] alleged various reasons, hatred to children, religious motives, a desire to preserve my beauty, and, finally this last year he told me his true reason... that he had imagined women were quite different to what he saw I was, and that the reason he did not make me his Wife was because he was disgusted with my person the first evening 10th April.

Ruskin was obviously not a homosexual and Effie, who later married the painter Millais, with Ruskin's blessings, was hardly unattractive and eventually became the mother of eight children. Ruskin's peculiar behaviour and explanations have been interpreted in a variety of ways. The most common theory nowadays is that Ruskin suffered from some kind of "genital terror". A feminist literary scholar, Sharon Weltman, has interpreted Ruskin's life-long fascination and fear of snakes as a sign of fear of female sexuality:

A phallic symbol, the serpent becomes feminine for Ruskin in The Ethics of the Dust...[when he] emphasizes the serpent's sinuous curves and feminine beauty...[T]he snake's importance for Ruskin rests in its ability not only to transcend gender but also to represent another stereotypically feminine principle, that of change and metamorphosis.

In Ruskin´s imagination snakes became a manifestation of female threats. Among several men´s imagination snakes are coupled with water and thus to threatening female water creatures. The mermaid's hair turns into a snare for capturing men and her fishtail, the proof of her dual nature, becomes the suffocating body of a snake. It is true that Ruskin in his frequent descriptions of snakes associated them with women and water.

Watch it, when it moves slowly:— A wave, but without wind! a current, but with no fall! all the body moving at the same instant, yet some of it to one side, some to another, or some forward, and the rest of the coil backwards; but all with the same calm will and equal way—no contraction, no extension; one soundless, causeless march of sequent rings, and spectral procession of spotted dust, with dissolution in its fangs, dislocation in its coils. Startle it;—the winding stream will become a twisted arrow;—the wave of poisoned life will lash through the grass like a cast lance.

The graceful, innocent water creature Undine in the book of the same name, which was placed on Wagner's bedside table, was a completely different woman than the likewise attractive but murderous mermaids and Rhine Maidens. She is an “elemental spirit” with her origins in alchemical speculations.

A few years ago I visited a surgery in Rome called Il Centro clinico Paracelso. A somewhat strange choice of a name considering that Paracelsus generally has been described as a charlatan and quack. Connected to the Centro Paracelso was a group of medical doctors with recognized expertise and I wondered why they practised their trade under the auspices of an alchemist, and assumed miracle worker.

Bombastus Theophrastus von Hohenheim (1490 - 1541) called himself Paracelsus, "Surpassing Celsus", a Roman alchemist from in the first century after Christ. Paracelsus, who claimed to be the "Christ of medicine” was a learned man and close friend of the respected Erasmus of Rotterdam. He served under several European royal houses, for a time he was personal physician to Christian II and did for several years live in Copenhagen and Stockholm.

Paracelsus believed in a careful observation and analysis of the patient, the disease and its relationship to the local environment. Probably was this conviction based on experiences from his time as a medical doctor in the German mining industry. He was first to establish the cause of silicosis and did by chemical analyses prove the presence of various metals in drinking water.

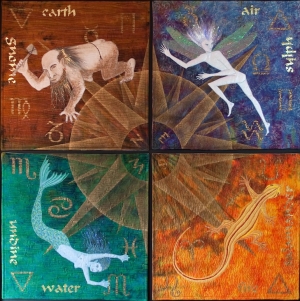

In some circles, like the staff of the Il Centro clinico Paracelso, Paracelsus good reputation is mainly based on his conviction that no cure could be accomplished without taking into account both body and soul. He assumed that everything is animated and his thoughts about the “elementals” is based on the belief that all creation is made up of the four elements; fire, earth, air and water. It is here that his speculations leave science and become increasingly whimsical. In one of his many treatises, Liber de Nymphis, sylphis, pygmaeis et salamandris et de caeteris spiritibus published after his death, Paracelsus described beings living within their respective elements, where they eat and drink, work, and battle, are born and die. Gnomes in the soil, in the air sylphs, salamanders in the fire and undines in water. Paracelsus lively and fantastic descriptions of the elementals have inspired poets, visual artists and writers, not the least Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

In the Prussian officer Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué´s tale Undine from 1811 is the ingenuous and beautiful Undine an elemental spirit who most of all wants to have a soul, a spirit can only get a soul if s/he marries a human. Undine succeed in getting married to the knight Hildebrand. However, like most creatures with an inhuman origin, she is unable to maintain her husband's love. The reason is that mortals fear anything that is different. Hildebrand´s repudiation of Undine is exacerbated by the elemental spirit´s false friend Bertalda, who becomes the reason for the lovely Undine´s final dismissal by Hildebrand and with a broken heart she returns to her element – the water. However, the water sprite´s love for Hildebrand cannot be appeased, and the knight cannot forget her. One night, Undine comes out of the castle well and seeks out Hildebrand, who welcomes her with a kiss, which leads to his death. Accordingly, the combination of femininity, water, passion and death have a strong presence in the story of Undine.

Undine like any good fairy-tale has its cold streaks of fright and confusion, like Ruskin describing how damp, chilly nights clutch Venice in their grip and lonely night hikers get lost in its maze of narrow streets, bridges and canals, and with rising panic wander around in circles without finding their way. Afraid of being assaulted or fall into one of its cold, dirty channels, without hope of salvation in a city which sometimes may appear as a ghost town. Jeanette Winterson writes in her strange novel The Passion:

This is the city of mazes. You may set off from the same place to the same place every day and never go by the same route. If you do so, it will be by mistake. Your bloodhound nose will not serve you here. Your course in compass reading will fail you. Your confident instructions to passers-by will send them to squares they have never heard of, over canals not listed in the notes.

The book I was reading on the train towards Venice appeared to confirm that I was heading to a mysterious realm. It was called Travel in moonlight and was written by Antal Szerb, a cosmopolitan with his roots in Budapest, admired and successful he was arrested in 1944 and was as a Jew deported to the concentration camp of Balf, where he after a month´s incarceration was beaten to death.

I had brought with me the book because I had read it would be about a confusing trip through Italy, written in a style akin to magical realism. The novel was certainly a strange acquaintance. Not least in view of the introduction where the protagonist finds himself on a train. He is called Mihály and is for the first time in his life traveling to Venice. He is in the company of his wife, whom he has just married. Surprised, I lifted my head from the book, looked around me and became aware that even I sat on a train going to Venice in the company of my wife, my oldest daughter and her boyfriend were also with me. He comes from the Czech Republic and is named Michal, the Czech equivalent of Mihály, for the first time in his life he was on his way to Venice and would in a few months´ time marry my daughter.

Some days later I wandered alone through Venice's narrow streets, it was mid-December, grey and cold. The others rested at the hotel, but I was on my way to a small haberdashery we had spotted during one of our walks through Venice´s back alleys. The boutique sold embroidered linen fabrics and I thought it would be a good place for purchasing Christmas gifts. The shop was far away from the usual beaten tourist track and oddly enough I found it without too much trouble.

The shop owner was a friendly, little lady from Klagenfurt in Austria. She obviously appreciated my attempts to converse in my fairly lousy German. She had lived in Venice for more than fifty years and told me she loved the city.

- However, it is not like before. Several years ago, most of my clients where Venetians and maybe a fifth were tourists. Now it's just the opposite. The original Venetians move away. Rents have become too expensive. The houses are being renovated and people whose ancestors have lived here for centuries can no longer afford to live here. Everything has changed. Venice has lost its popular character. The population decreases. The great pleasure of sharing your life with friendly neighbours is disappearing. The homey feeling of my neighbourhood is almost gone. But nevertheless it is a wonderful place.

When I returned I was completely lost, but I did not dislike the experience, I felt like Mihály in Antal Szerbs novel:

Narrow little streets branched into narrow little alleyways, and the further he went the darker and narrower they became. By stretching his arms out wide he could have simultaneously touched the opposing rows of houses, with their large silent, windows, behind which, he imagined, mysteriously intense Italian lives lay in slumber. The sense of intimacy made it feel almost an intrusion to have entered these streets at night. What was the strange attraction, the peculiar ecstasy, which seized him among the back-alleys? Why did it feel like finally coming home? Perhaps a child dreams of such places, the child raised in a gardened cottage who fears the open plain.

In the Venetian alleys the casual visitor is reminded about the fact that Venice contains much more than tourists and millionaires, palaces and churches packed with art. There are also people who spend their daily lives in the city, with all it implies of cooking, shopping, refuse collection, leaking pipes and problems with electricity and utility bills.

The peculiar Frederick Rolfe, an imposter, supposedly defrocked priest and former monk, who several readers regard as a brilliant writer, died in Venice in 1913. He ended his life in utmost misery, hopelessly entangled in a criminal world, within which he apparently thrived as fish in water. He was in fact a water creature who considered Venice to be his true element. He lived on a boat and swam several hours a day in the city's canals:

Deep water I must have - as deep as possible – I being what the Venetians call 'Apassionato por aqua'.

In one of his letters Rolfe described how he at nights used to row far out in the lagoon, he had through his gondolier friends been taught how to manoeuvre their strange crafts:

Popping silently overboard to swim for an hour in the clear of a great gold moon – plenilunio – or among the waving reflections of the stars (Oh, my goodness me, how heavenly spot that is!).

However, the homosexual Rolfe was like a mythical water creature, a callous predator who pulled young men with him into the depths and abandoned them there. He was a con man and a pimp. His biographer A.J.A. Symons described in his fascinating biography of Rolfe, published in 1934, how upset he became when he got hold of some of Rolfe´s correspondence:

What shocked me about these letters was not the confessions they made of perverse sexual indulgence, that phenomenon surprises no historian. But, that a man of education, ideas, something near a genius, should have enjoyed without remorse the destruction of the innocence of youth: that he should have been willing for a price to traffic in his knowledge of the dark byways of that Italian city; that he could have pursued the paths of lust with such frenzied tenacity: these things shocked me into anger and pity.

Although he quite often managed to hoax or beg someone for support, shelter and money, the benevolence of Rolfe´s various benefactors tended to be exhausted rather quickly, in particular since he was in the habit of gossiping and often vilified people he felt had aggrieved him. Rolfe fell deeper and deeper into destitution and disease:

Desperately sliding downhill, unable to pay for clothes, light or food; living like a rat at the bottom of an empty boat, slinking along side streets in misery at frustrated talents and missed chances, with no money in his pocket or meat in his belly...

Fredrick Rolfe´s horrid fate and the illicit world he lived in, must have appeared as utterly alien to wealthy tourists who had been taken in by Venice´s dazzling beauty and charm.

For several tourists the realization of the presence of poverty and crime in Venice could come as a sudden shock. The intrusive presence of a proletarian environment was probably more prominent by the beginning of the last century. In Leslie Hartley's short novel Simonetta Perkins, the protagonist, Lavinia, a rich young lady from Boston, witness a knife fight close to the Rialto Bridge. Her companion proclaims enthusiastically that he is glad to have witnessed it. "So typically Italian" exclaimed Stephen, one of Lavinia cavaliers:

'Your real Italian,' he said, mimicking the action, 'always stabs from underneath, like this.'

Lavinia shudders at the ´sight of the excited spectators, Stephen´s enthusiastic bloodlust appals her, as well as the thought that she had got a glimpse of the dark, poor, criminal side of Venice.

Hartley's story plays on the sharp distinction between the impoverished Venice and the crowds of wealthy tourists. Lavinia has become infatuated by Emilio, a handsome gondolier and later hopelessly in love with him. Her mother is nagging incessantly, reminding Lavinia that she is becoming old and can no longer dismiss rich suitors or avoid socializing with the wealthy people she wants her daughter to be hanging out with.

Every time Lavinia manages to eschew the mother and her intrusive admirers and spend a quiet moment in the gondola, which is rhythmically paddled by the taciturn Emilio, she is happy. Though Lavinia is painfully aware of the sad fact that it would be impossible for her to marry a gondolier.

People from Lavinia´s wealthy surroundings suggest that it is inappropriate to be too intimate with "one´s gondolier". According to Lavinia´s Anglo-American companions, most of the attractive gondoliers are vulgar gigolos, constantly prepared to be paid for the amorous services they might offer. When Emilio extends his hand to help an English lady from his gondola, her husband sputters:

‘You know,' he said, ‘you touch those fellows at your own risk.'

‘Nonsense, Henry,' his wife protested. ‘Why?'

‘Oh, plague, pestilence, dirt, disease,' Lord Henry answered.

Lavinia also becomes upset when Emilio one day arrives to pick her up at her hotel and she does in the merciless electric light for the first time see him as the poor man he really is. Emilio seems to be lost within the unfamiliar setting, his arms are indecisively hanging by his sides. He appears to be forlorn and painfully submissive.

By the end of the story Lavinia gathers all her courage. She knows her feelings towards Emilio are answered, in the intimacy of the gondola she turns around towards Emilio, where he stands, handsome and quietly smiling by the long oar: Ti amo! she exclaims. But the gondolier puts on a deaf ear and responds with the routine: Commandi, Signorina! “Command Miss!” indicating that Lavinia has to tell him where she wants to go, she understands it is a lost case:

With each stroke it [the gondola] shivered and thrilled. They turned into a little canal, turned again into a smaller one, almost a ditch. The V-shaped ripple of the gondola clucked and sucked at the walls of crumbling tenements. Ever and again the prow slapped the water with a clopping sound that, each time she heard it, stung Lavinia's nerves like a box on the ear.

To fully comprehend the unfulfilled romance between Lavinia and her gondolier we should know that before vaporettos and motorboats made their entrance in Venice, it was common for wealthy visitors to hire a personal gondolier, who from the hotels or palaces where they lived routinely took them on sightseeing tours and to various engagements.

The intimacy between a gondolier and his craft became clear to me when we one morning, at one of the city's smaller canals, saw a gondolier who removed the tarpaulin from his gondola. My wife went up to the edge of the canal and began to inquire the gondolier about his profession. Cheerfully and willingly he told us that the job is generally passed on from father to son, but anyone can buy a gondola and obtain the necessary permits. However, it is not possible to purchase any gondola, they are made to measure at a gondola wharf, where they are built in accordance with the client's weight and height, otherwise the craft will be difficult to manouver:

- I have to think about what I eat and stay in shape to maintain the correct weight for my boat! laughed the gondolier.

There was a full moon when I strolled alone among the back alleys and canals. Between the dark buildings, I could occasionally glimpse the canals´ water becoming silvered by the moonlight. The coobled streets were damp, cold and deserted. Unexpectedly, I ended up on the Campo dei Frari. Before me rose the vast Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa. As Henry James had written - Venice "has a thousand occasional graces and is always liable to happy accidents." The moon stood still by the crest of the mighty campanile. How could something so big and heavy have been built on one of Venice's marshy islands? I stood on the deserted piazza, exultant and overwhelmed. Can such feelings be shared?

It is seldom the splendid and overpowering is mentioned in connection with Venice. Most fiction I have read about the town has been focused on the intimate, the sensual and the frightening. I am thinking about the stories I mentioned at the beginning of this essay. Death in Venice in which the feverish and dying Gustav von Aschenbach staggers round in alleyways in search of the angelically handsome Tadzio. Or the unhappy couple in Don´t not look now, who after losing a child try to repair their broken relationship, but end up in the hands of a strange couple of psychics and then wanders around among bridges and canals. The wife leaves her husband to journey back to England, but the man believes he glimpsed his wife in Venice and also a little creature dressed in bright red, who he vaguely imagines being his drowned, little girl, though it all turns out to be harbingers of his own death. Or the newly married couple in the The Comfort of Strangers who search for each other in a fumbling, awkward love until they get lost in the alleys and are captured by a predatory couple, who use them for their own perverted purposes.

These three stories seem to unfold in a dreamlike, parallel world, described by the young lady's feelings in The Comfort of Strangers:

For Mary the hard mattress, the unaccustomed heat, the barely explored city were combining to set loose in her sleep a turmoil of noisy, argumentative dreams which, she complained, numbed her waking hours; and the fine old churches, the altar-pieces, the stone bridges over canals, fell dully on her retina, as on a distant screen.

Are all depictions Venice equally alienating? Are lost strangers perpetually wandering around the city streets? Is Venice a city which seems to be alive through a feminine essence? A few days ago I bought, for one euro, a used book titled Miss Garnet´s Angel, it turned out to be about a recently retired, English lady who haphazardly heads to Venice and stays there. Like the other books I mentioned it seems that he town itself interacts in the story and although the lady in question does not get involved in any love relationship, there is also in that novel hints of sensuality and a confused longing for love.

I recently reread a rather charming, sober and objective portrayal of Venice by James Morris, who with great empathy tells us about the town, its daily life and history. The author writes not so much about Venice's female charm and power of seduction, but explained that his book was “a highly subjective, romantic, impressionist picture less of a city than of an experience.”

Perhaps the "experience" affected James Morris in a rather tumultuous fashion, maybe it could have been the city's feminine fascination that induced Morris, shortly after the book's publication in 1960, to start a hormone treatment which ten years later had transformed him into a woman. He, or more accurately she, is now named Jan Morris, though on the cover of my edition of Venice from 1974 she is still James.

James Morris change of gender brings us back to the lesbian Jeanette Winterson´s description of the Napoleonic Venice in her The Passion, in which she depicts the town as sexually transgressive and metaphoric, where erotic desire during carnival time no longer can be contained by any fixed social codes and the entire place becomes fluid, unstable, labyrinthine and amphibious, while binary gender divisions are dissolved.

Henry James wondered in the introduction to his depiction of Venice - why once more write about Venice? Does not each and everyone us know how Venice is? What the city looks like? Have not people around the globe seen thousands of images and through countless knickknacks learned about its canals, piazzas and gondolas? Yet Henry James could not avoid to once again write about Venice. The awe he felt in the city forced him to do it. And he wondered - what could be wrong about once more searching for things and feelings believed to be familiar, to retell old stories? Why must everything be a novelty? Anyway, few things and experiences are really news. And after all - Venice never ceases to speak to us. Every time we arrive there, the city has something to tell us – it could be new or old, it does not matter, for amidst maturity and squalor she remains the same old Venice; mysterious and alluring. La Serenissma.

Auerbach, Nina (1982) Woman and the Demon: The Life of a Victorian Myth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Clark, Kenneth (1967) Ruskin Today. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books. Crane, Patty (2015) Bright Scythe: Selected Poems by Tomas Transtromer. Louisville KA: Sarabande Books. Donder, Vic (1992) Le chant de la sirène. Paris: Gallimard. Dickens, Charles (1997) American Notes and Pictures from Italy. London: Everyman/J.M. Dent. du Maurier, Daphne (2006) Don´t Look Now and Other Stories. London: Penguin Modern Classics. Gilmore Holt, Elizabeth (1982) A Documentary History of Art, Volume 2: Michelangelo and the Mannerists. The Baroque and the Eighteenth Century. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Gitter, Elisabeth G. (1984) "The Power of Women's Hair in the Victorian Imagination" in PMLA. Vol. 99, No. 5. Hartley, L.P. (2004) Simonetta Perkins. London: Hesperus Classics. Kramer, Lawrence (1990) Music as Cultural Practice. Berkeley: University of California Press. Mann, Thomas (1999) Death in Venice and Other Stories. London: Penguin Classics. McEwan, Ian (1981) The Comfort of Strangers. London: Cape. Nataf, Andrè (1988) Le maîtres de l´occultisme. Paris: Bordas. Morris, James (1974) Venice. London: Faber & Faber. James, Henry (2008) The Wings of the Dove. London: Penguin Classics. James, Henry (1995) Italian Hours. New York/London: Penguin Classics. Ruggiero, Guido (1989) The Boundaries of Eros: Sex, Crime and Sexuality in Renaissance Venice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Steer, John (1970) A Concise History of Venetian Painting. London: Thames and Hudson. Symons, A.J.A (1966) The Quest for Corvo: Genius or charlatan? An experiment in biography. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. Szerb, Antal (2014) Jouney by Moonlight. New York: NYRB Classics. Thackeray, William Makepeace (1987) Vanity Fair. London: Penguin Classics. Tully, Carol (ed.) Goethe, Tieck, Fouqué, Brentano: Romantic Fairy Tales. London: Penguin Classics. Vickers, Salley (2002) Miss Garnet´s Angel. New York: Plume. Weltman, Sharon Aronofsky (1997) “Mythic Language and Gender Subversion: The Case of Ruskin's Athena” in Nineteenth Century Literature, Vol. 52, No. 3. Winterson, Jeanette (2014) The Passion. New York: Vintage.