MAD WOMEN: Hedda Gabler, Unica Zürn and Leonora Carrington

About a week ago, I saw Ibsen's Hedda Gabler in Hässleholm. It was a performance by the to me unknown Theatre of Halland and my unfounded prejudices against local theaters came to naught through a fast-paced and well-acted show. Since then I have occasionally pondered about the play.

Is Hedda Gabler crazy? I assume she must be utterly disturbed. A sensible woman would not encourage the man she loves to commit suicide by offering him a loaded pistol along with the admonition: "And in beauty, Eilert Lövborg. Just promise me that."

When the suicidal Eilert has left her alone, Hedda burns his brilliant book manuscript, which he assumes he has lost, something that triggers his decision to kill himself. Eilert has written the manuscript with the help of Hedda Gabler´s despised rival, Thea Elvsted and with a smile the jealous Hedda throws it into a stove with the words: "Now I burn your child, Thea - you with the curly hair. Yours and Eilert Lövborg´s child. Now I burn - I burn the baby." Then she lies, convincing her somewhat inane husband that it was for his sake she burned the manuscript. Hedda´s husband and Eilert are applying for the same professorship and the publication of Eilert's book would have made her husband's writings appear as mediocre.

When Hedda is informed about Eilert's death, she exclaims: "At last, a deed!" and adds that there is beauty in death by one´s own hand. According to her, Eilert Lövborg had been blessed by the courage to live his life in accordance with his inner self and furthermore had had the strength and determination to break free when all went wrong. But when she learns that Eilert died of an accidental discharge within a brothel, Hedda Gabler´s enthusiasm turns into cruel disappointment. The pistol that had been loaded and decocked by Hedda fired by itself while Eilert wore it in his breast pocket, his death agony was prolonged and pathetic, far from being beautiful.

Like most of Ibsen's dramas Hedda Gabler is multi-layered and suggestive, far from being politically correct. Hedda is both crazy and insightful, a full-fledged psychopath, but her madness is headstrong and, like Hamlet's madness, it has a method. It is a result of and unfolds within the confines of an enclosed society. Of course, Hedda contains traits of her creator. Ibsen who observed the world from "the outside" and stated that he would like to "know everything, but keep myself clean."

Hedda is one of Ibsen's passionate, intellectual women who, like wing clipped geese move around within the confines of Norwegian, bourgeoisie duck ponds, where more or less unconscious men are chattering like unsuspecting fowl, blinded by their own excellence, or general anxiety. Ibsen realized that some women may have insights that thoughtless and privileged men are unaware of. His fictional female characters often stand by his side in his struggle against a stagnant, patriarchal society. When Ibsen's character Peer Gynt meets the strange creature Böjgen, which is like "a fog, anxiety and a stagnant swamp; the sum of all living sluggish dregs" the monster cannot hurt him. It pulls away from Peer Gynt with the words: "He was too strong. There were women behind him."

Like Rebekka in Rosmersholm and Ellida in The Lady from the Sea Hedda Gabler conceals clandestine rebellion and inarticulate love. All of them end up as losers, albeit of a different kind – the lonely and desperate Hedda shoots herself, Rebekka chooses death along with Rosmer, whom she gradually has learned to love and who loves her, while Ellida opt for the safety of home and husband instead of losing herself in her passion for an alluring stranger.

That Hedda Gabler has become regarded as particularly crazy is certainly due to the fact that her rebellion assumes nasty expressions. She is a victim of her own bitterness, and like a cat she cynically amuses herself with victims in her immediate environment. Hedda is an aristocrat, intelligent but apparently without much thirst for conventional knowledge and behaves like an aggressive, frustrated man trapped within a macho society. She does not recognize the fetus she is carrying, flaunting her sex appeal. She is being coveted by men around her without being invited to their inner circles. In those days women lacked suffrage and were denied academic careers. Trapped by her wild passions Hedda Gabler remains cold and inaccessible, despite her dreams of uninhibited revelry, declaring that like a bacchante she wants to carry "vine leaves in her hair."

Freud was well acquainted with Ibsen's dramas and wrote a psychoanalytic study of Rosmersholm. Many of Ibsen's characters are like Freud's patients neurotics trapped within their own past. The plot of a typical Ibsen play is unraveled as in a psychoanalytic session, being gradually reveled until calamity and tragedy hits the participants in the drama. What in the beginning may appear as a tranquil idyll is eventually being exposed as an unsound environment where a seemingly harmonious surface hides huge and ugly monsters.

Ibsen asks us whether we are to liberate ourselves from a burdensome past, but unlike what Freud pursued through his psychotherapy there is seldom a happy ending. Few of Ibsen's characters find themselves and get to enjoy the security and harmony they long for. They die or continue to stumble into an uncertain future. For them, life is an impossible project. Ibsen is not a doctor, but a great writer. Perhaps Freud was a better author, than doctor. Like Ibsen he is present in his own writing. Freud´s "research", his psychotherapy, remains an interpretation of existence, like a novel or a play that reflect an undefined reality For sure, both great literature and psychotherapy may transform a person that has been exposed to it. Perhaps Freud would have received his Nobel Prize in literature instead of medicine.

Freud found at least as much inspiration from fiction as from his activities as a physician. He devoted several of his analyses not to living people, but literary figures. It may be Greek dramas like Oedipus the King, or contemporary theatre like Ibsen’s oeuvre. There is drama in madness and as well as in the theatre world there are in lunatic asylums spectators who assess and interpret speech and conduct.

I have in a previous blog post written about how Jean-Martin Charcot in the 1880s presented hysterical women for an audience at the Parisian Salpêtrière hospital. They were elegant events where you could meet not only physicians among the audience, but also world famous members of the cultural elite. Edmund Goncourt wrote in his diary that Charcot had a "visionary´s and a charlatan´s physiognomy", coupled with the ability to use "intellectual experiences" that could turn a spectator´s entire view of the world upside down.

To his fiancée Freud wrote that Charcot "who is one of the greatest of physicians and a man whose common sense borders on genius, is simply wrecking all my aims and opinions.” Freud stumbles deeply shaken out from Charcot´s demonstrations, stating that: "My brain is sated as after an evening in the theatre. Whatever the seed will ever bear any fruits, I don´t know; but what I do know is that no other human being has ever affected me in the same way.”

Freud likened the "unconscious” to the invisible parts of an iceberg, which have a far greater extent than is visible above the surface. The Surrealists founder and eventually self-appointed dictator, Andre Breton, who like Freud started as a medical student, abandoned his medical career due to his experiences at the “nerve clinics” that were established during the First World War. He became a writer who dived into the subconscious in order to bring about its potential, fostering what he labelled as unbridled creation. In the first Surrealist Manifesto, which he wrote in 1924, Breton noted that by indulging in fantasies and dreams you may conjure an inner reality, which is at least as true as the one we call "everyday existence". Art could become a liberating process, a

pure psychic automatism that is intended to convey, either verbally, or in writing, or in some other manner, the real functioning of thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason and apart from any aesthetic or moral consideration.

Freud considered himself to be a clear-minded scientist far removed from any kind of artistic speculation and could thereby sometimes feel bothered by the surrealists’ tributes to him as their champion. It was not Freud's psychological system they celebrated, but the fact that they considered him to be a prophet who through his revolutionary research had been able to open up the gates to the poetic, mystic and creative forces that lay hidden within every human being. Freud wrote to Breton:

Although I have received many testimonies of the interest you and your friend show for my research, I am not able to clarify for myself what Surrealism is and what it wants.

Who could be sure about what “surrealism” was and wanted? The scope and different means of expression of artists who usually are labelled as "surrealists” are extensive. Salvador Dali is commonly believed to be a surreal prime specimen, but in his persona and art he represents just a fraction of a wide-ranging movement. Nevertheless, his widely quoted musing that: "The only difference between Salvador Dali and a madman is that Salvador Dali is not crazy" may be used as motto for the tendency to deliberately let the uncontrollable take hold of you, something that can mean a balancing act dangerously close to madness. Several surrealists ended in the madhouse. Two of the movement's foremost female representatives have written classic descriptions of their visits "down there", i.e. in the realm of madness. One reason for my appreciation of HeddaGabler could have been that the night before I saw the show I read two short "autobiographies "- Unica Zürn´s The Man of Jamine and Leonora Carrington'sDown There.

The first time I read Zürn´s description of her recurring stays in various mental hospitals was while I was living in Paris. Without knowing anything about the author, I had for a few crowns bought her book in a secondhand shop in Bjärnum. While in Paris, I discovered that she and the perverted artist Hans Bellmer had lived in a place not far from my studio apartment. The hotel where they shared two dingy rooms does not exist anymore, in its place there is now a restaurant, Le PetitLéon, where I occasionally had my supper unaware of the fact that two of the rooms above me once had been inhabited by two more or less crazy artists. After reading Zürn´s book I asked the English-speaking waiter if he knew that the restaurant was located at the same address as what once had been Hotel de l'Espérance, but he did not know anything about that.

There are some similarities between Unica Zürn and the fictional Hedda Gabler. Both kept their father's name after marriage and seem to have been tied to their fathers, who both had been cavalry officers. In the play, Hedda's father is mentioned several times, but not her mother. Unica Zürn writes with longing and admiration about her father, but with horror and contempt about her mother:

Overtaken by an inexplicable feeling of loneliness, she enters on the same morning her mother's room […] the daughter climbed into the bed beside her mother and was appalled by how the mountain of tepid flesh which encloses this woman´s impure spirit rolls over on the horrified child, and she flees forever from the mother, the woman, the spider! She is deeply grieved.

Unica Zürn was fifteen years old when her parents divorced and she was forced to leave her beloved childhood home, which she often describes:

The house and garden of her childhood in Grunewald. She walks up and down the stairs through the twelve rooms, and gazes into the winter fire in the hearth of the large hall. She touches the Asian and the Arabian furniture her father had brought back from his travels, and which, rather than making a museum of the house turned into a beautiful cave which stirs the imagination. She looks at each object, every picture, all the colours and forms. This is a memory exercise she has repeated to the point of perfection over all the years which followed the large auction in which everything, almost everything with which she had grown up, was sold off. In fact not a day has passed since her fifteenth year on which she has not performed the invisible walks round this house. She has never overcome the pain of having to leave this house.

Her father had been a writer and publisher. In his youth, he served in Germany's African Corps and then traveled around the world. It seems that Zürn´s adored father, who was not always present in the home, coincided with a male dream figure she invented. He followed her throughout life in the shape of The Man of Jasmine: "He never leaves the armchair in his garden, where jasmine bloom even in the winter."

Eighteen years old Unica began working as a secretary and archivist at the German film company Ufa. In 1942 she married a man she divorced seven years later. She lost the custody of their two children. Apparently, the husband claimed that she was mentally unstable. During the custody dispute the somewhat dubious Wartegg drawing test was used as evidence of Unica´s mental instability. Ten years later, when she was interned for psychiatric care, the same test method was used to declare her as an incurable schizophrenic.

After hthe divorce Unica supported herself as freelance journalist in Berlin until 1954, when she encountered the artist Hans Bellmer and moved with him to Paris, where she was introduced to his friends among the Surrealists. Bellmer´s uninhibited art with its hints of sadism and pedophilia was admired by a small, but influential, group of writers and artists. Among the so called "transgressive philosophers” it had become fashionable to pay tribute not only to Nietzsche, but also to the unsavory Donatien Alphonse François de Sade, who they hailed as the “Divine Marquise”. Transgression was defined as surpassing social and sexual structures. To indulge in the “frontier areas of human behavior” was for these artists an undisputable method to achieve consciousness and knowledge. Insights into the fundamental conditions of existence were primarily gained not through the mind, but through the body and an acknowledgement of carnal desire. Georges Bataille, who may be regarded as the movement's figurehead, declared that:

The paradox of existence […] is to go beyond our limits and yet, at the same time, it is apparent that if we were to do so we should in fact cease to exist. The most we can do, therefore, is to experience the vertigo at the edge on which our life unfolds.

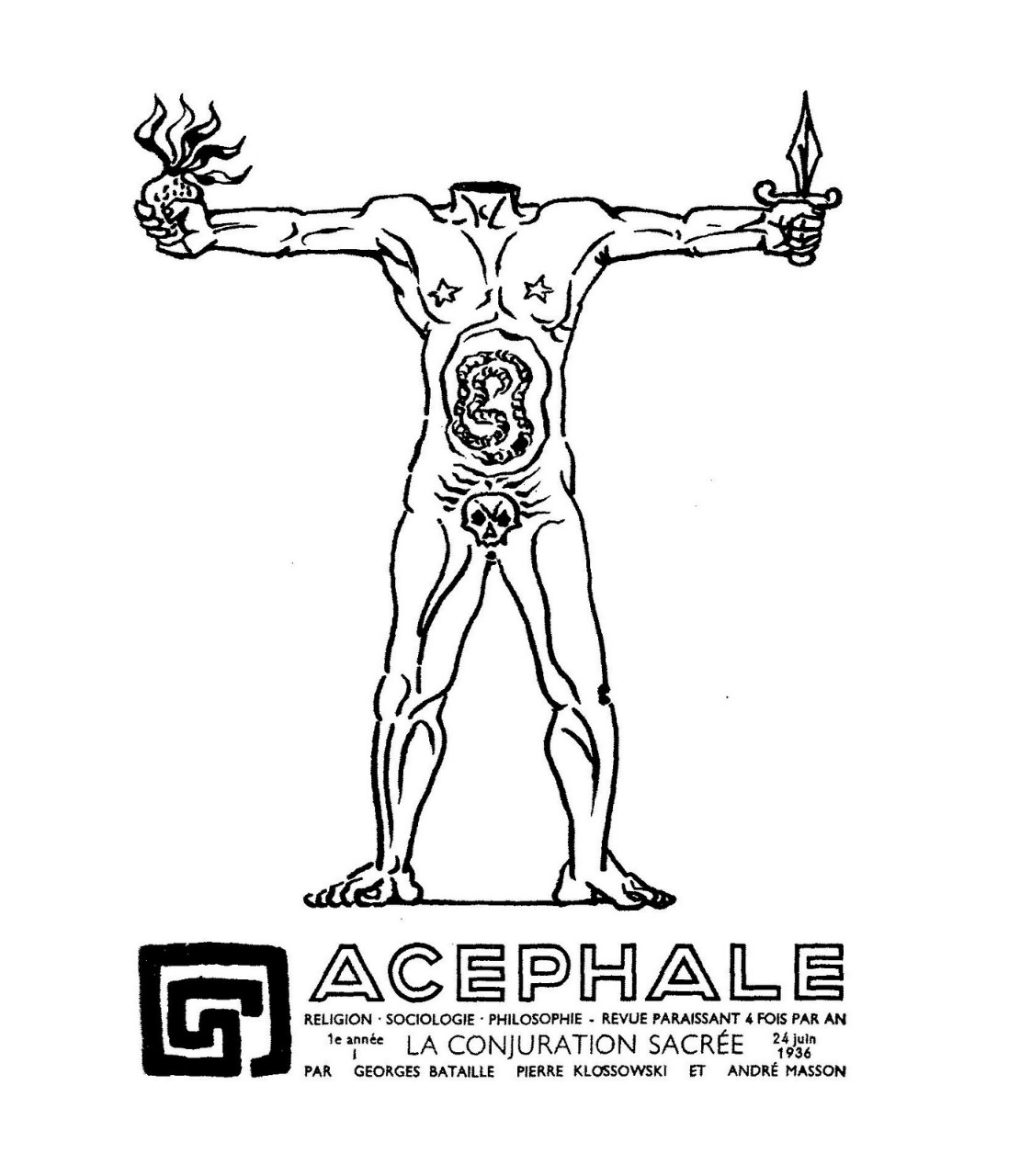

Around the magazine Acéphale of which Bataille edited five numbers before the outbreak of the Second World War a circle of artistic friends gathered with a common interest in rituals, mysticism, alchemy, pornography, anarchy, incest, necrophilia, sadism, pedophilia and other extreme manifestations of odd human desire. Acéphale´s cover, created by the surrealist artist André Masson, provides an idea of the group's interest in the body, passion, violence and mystery - a headless man whose groin is covered by a skull and who in his right hand holds a burning heart, while his left hand wields a dagger. After the war the group continued to be influential within certain surrealist coteries.

Unica Zürn thrived among these men. Hans Bellmer was an excellent graphic artist and it became popular among the surrealists to ask him to draw their portraits:

I was allowed to accompany Bellmer during all the portrait sittings: Man Ray, Gaston Bachelard, Henri Michaux, Matta, Wilfredo Lam, Hans Arp, Victor Brauner, Max Ernst…There are those who must be adored and others who adore. I have always belonged among the latter. Being full, constantly full of wonder, admiration and adoration. Remaining in the background, watching, looking—that is the passive manner in which I lead my life.

Unica Zürn submitted herself to Bellmer´s desires and let herself be exposed in a variety of pornographic drawings and allowed him to photograph her tied up, as if she had been a pork roast. Bellmer was a radical person and a bold anti-Nazi, who during the war manufactured false identity documents for members of the French Resistance. His sharp-lined artwork and eerily lifelike dolls were hailed for their "dark eroticism" and innovative metamorphoses of the human anatomy. Nevertheless, I am repulsed by Bellmer´s undeniable tributes to sadism and pedophilia, and refuse to be duped by Bellmer´s numerous admirers who claim that his works are neither repellent, nor grotesque, only explicit and dreamlike.

In her well-written and strangely incisive description of her journey through madness Unica Zürn describes how she in 1957 met the artist and writer Henri Michaux:

… she experiences the first miracle in her life; in a room in Paris she finds herself standing before The Man of Jasmine. The shock of this encounter is so great that she is unable to get over it. From this day on she begins, very very slowly to lose her reason

Michaux was a seeker who traveled all over the world - Japan, China, India, Ecuador, Brazil and several African countries - constantly in search of himself. Furthermore, he made inner journeys using ether-snorting, mescaline and LSD. In this pursuit he brought Unica Zürn with him. He also inspired her to write poems, make ink drawings and search for mysterious messages in her immediate environment. Drug abuse, combined with the anguish she experienced after an abortion forced upon her by Bellmer in 1959, steered Unica towards a free-fall into madness.

A scene in Unica´s record of her entry into madness makes me think of how Hedda Gabler was portrayed in the performance I saw. On several occasions she imitated various animals. I have not checked if this behavior is specified in Ibsen's stage directions - I don´t think so. The director probably intended to represent Hedda Gabler as an exotic animal caged in by the stuffy, Norwegian bourgeoisie.

After being detained at a hideous mental hospital in Berlin, Unica suffers a violent psychotic attack, alone in a Parisian hotel room. This is the Paris that Henry Miller described in his novel The Tropic of Cancer:

… Paris attracts the tortured, the hallucinated, and the great maniacs of love. I understood why it is that here, at the very hub of the wheel, one can embrace the most fantastic, the most impossible theories without finding them in the least strange.

Unica who to begin with lays sleepless in her hotel bed, gets up, goes to the window and is caught by the view which opens up to her; how the nocturnal Paris spreads out in front of her. The city she loves and which loves her. Being entranced by the spectacle in front of her, she

notices that the house seems to be floating above the ground and that the people who have reappeared in order to enter it are moving on several streets, constructed in the air, which intersect the beautiful architecture of rays and rise and sink with a gentle motion. A paradisiacal picture. The happy, eternal hunting grounds of her childhood. […] Somewhere in the darkness he [Michaux] is guiding her, the teacher directs his pupil. Without she being able to control it herself her first finger begins to move, the wrist is bent, the hand describes a neat little arch in the air: the dance has begun. And she lies in her bed watching herself.

Her fingers become five persons; feet, legs change shape. She makes the snake, unfolds, it turns into a shining star, a beautiful, flower-like pattern, a light sheet of paper floating through the air. The hand becomes a bird; the fingers grow, turning themselves into long, dangerous bird beaks, a large tropical bird which comes down to the water to drink. The audience is mesmerized and shouts: "Do the Tiger!" And she does the tiger, the scorpion killing itself with its own sting. The crowd cheers.

Unica´s insane ballet seems to mirror Michaux´s mescaline induced visions that he, for example, describes in La Nuit Remue, The Moving Night, written in the thirties:

In my little room animals come and go. Not at the same time. Not intact. But they pass by – a petty, ludicrous procession of the forms of nature. The lion comes in with his lowered head bruised and dented like an old ball of rags. His poor paws flapping. It´s hard to see how he can move forward – wretchedly, in any case. The elephant comes in, all deflated and less solid than a fawn. And so it goes for the rest of the animals.

Unica Zürn did not recover from her anxiety attack in the Parisian hotel room and spent the rest of her life between different mental institutions and nursing homes. Among others she was treated by Gaston Ferdière, a doctor who had also taken care of Antonin Artaud, who accused him of imposing "the horrors of electroshocks on me 50 times in 3 years in order to make me lose the memory of myself, which he found far too conscious”.

During periods of temporary recovery Unica Zürn wrote, between 1963 and 1965, her book The Man of Jasmine, which she dedicated to her children, Christian and Katrin, of whom she had lost custody of 1949. The book is written in the third person and is neither bitter nor dismal. Even while Unica describes abysmal psychotic states she retains an ability to observe herself and her environment. She discloses the doctors´ cynical interest while they are testing various medications, like majeptil which resulted in her muscles retracting themselves in painful cramps. Unica forced herself to concentrate her mind on a radio's red dot. It resembled "a small, artificial flower" and her contemplation of it helped her to "keep her head above the surface of the sea of torture she was floating in." She noted that:

The doctors are pleased, through her example they realize that the medicine produces stiffness. She begins to hate doctors. Her depression does not disappear.

In the autumn of 1970, Unica is granted a five-day furlough from the asylum and arrives at the apartment she shares with Hans Bellmer, but she finds him decrepit and bedridden after a stroke. The following day she killed herself by jumping out the window. Bellmer, who through his conscious flirtation with insanity, delirium and perversions probably had been a contributing factor to Unica´s mental illness mourned her deeply and died five years later. I saw their tombstone in the Pere Lachaise cemetery, the inscription had been chosen by Bellmer: "My love will follow you into eternity."

The clinic where Unica had been treated by Dr. Ferdière was named Lafond, a name she writes as Le Fond, a word that actually means "backdrop" but she interprets it as "the bottom" or "the depth", something that made me think of Leonora Carrington's description of her time in a mental hospital she called Down Below.

Leonora Carrington was the unruly and talented daughter of a wealthy, English textile company owner. Twenty years old she fell in love with the 26 years older artist Max Ernst, who was a world-famous surrealist and followed him to Paris. It was a wild passion. Ernst left his wife, his second one, in Paris and lived together with Leonora in the village of Saint-Martin-d'Ardèche, north of Avignon. They lived in an uninhibited, bohemian manner, decorating their house with reliefs, paintings, reliefs and sculptures. By the end of 1939 Max Ernst was interned by the French authorities and a panicking Leonora was left alone in the big house.

Max Ernst's fate was shared with a large number of intellectuals of foreign origin. This flagrant injustice has been described by the Hungarian author Arthur Koestler in his book Scum of the Earth, which deals with France's disintegration after the country's declaration of war against Germany in September 1939. Koestler was interned in the camp Le Vernet situated in southern France, while Max Ernst ended up in Le Camp des Milles outside Marseilles. Ernst shared his relatively mild imprisonment with well-known artists, writers and Nobel laureates. In the camp he became good friends with Hans Bellmer and they were able to jointly develop a technique called decalcomania, which meant that they spread paint over a glass plate, which was then pressed onto a sheet of paper or a canvas.

When France surrendered on the 25th June 1940 the country was divided into a German-occupied part and a French "free zone". The camps of Le Vernet and DesMilles ended up under the administration of the Vichy regime. The sites expanded rapidly through the influx of opponents to Hitler, Mussolini and the Vichy regime, as well as Jews and Gypsies. During the summer of 1942 the French police intensified their hunt for Jews and Gypsies. The camps were transformed into centers of rassemblement, regroupment, encampments where people were incarcerated awaiting there transference to Drancy outside of Paris for further transport to their final destination - the extermination camps further east. As an outspoken Nazi opponent even a famous German artist like Max Ernst lived dangerously.

Max Ernst went in and out of the camp. The first time, Leonora Carrington had notified influential friends who after four months managed to convince the authorities to release Max Ernst. But after four months of freedom, he was once again arrested; a villager had reported him as a "hostile alien". Ernst managed to escape, but was caught again. The Vichy regime was now considering to hand him over to the Gestapo.

Within this chaos Leonora Carrington suffered from of eating disorder, her menstruation ceased, she was seized by paranoia and hallucinations. Convinced that Ernst had been lost forever, she wrote over the house to a local official and traveled with a friend to Andorra, awaiting admittance to Spain. When her wealthy father, who had influential Spanish business contacts, managed to obtain a residence permit for his daughter, she had lost her wits; wandered around in Madrid, was raped and believed herself to be pursued by criminal gangs and evil-minded warlocks. Her condition worsened when she believed that she was being hypnotized and controlled from afar, imagining that she alone had been chosen to "save the whole of Madrid". Finally her English family arranged to have her locked up within a mental hospital in Santander.

It was obviously a facility designed for patients with wealthy families. It had a large garden, beautiful buildings and rather decent housing for its inmates. Unfortunately, the treatment of severe psychoses was concentrated to a so-called "convulsion therapy", which meant that patients were intravenously administered with cardiazol, a substance that plunged them into violent convulsions. The treatment was associated with intense discomfort. Patients were for several days strapped naked to their beds and there was a risk of life-threatening aftereffects. Several of those who had been treated with cardiazol suffered from incurable bone injuries and some suffered heart failure leading to death.

Leonora spent days and nights naked and strapped to a bed, but occasionally she was allowed to wander through the institution's garden, which she in her overwrought imagination turned into an alchemical wonderland, where sun and moon interacted with fairytale castles, which in reality consisted of hospital pavilions and thorny bushes. The central building, which she called Down There, became with its library and brightly lit halls a kind of paradise where she wanted to end up after having been liberated from her soiled bed.

Like Unica Zürn Leonora danced when she felt relieved and then imagined herself to undergo various metamorphoses, as with Unica her fingers got a life of their own:

Later, with full lucidity, I would go Down Below, as the third person of the Trinity, I felt that, through the agency of the Sun, I was an androgyne, the Moon, the Holy Ghost, a gypsy, Leonora Carrington, and a woman. I was she who revealed religions and bore on her shoulders the freedom and the sins of the earth changed into knowledge, the union of Man and Woman with God and the Cosmos, all equal between them. The lump on my left thigh no longer seemed to form part of my body and became a sun on the left side of the moon; all my dances and gyrations in the Sun Room used that lump as a pivot. It was no longer painful. For I felt integrated into the Sun. My hands Eve (the left one) and Adam (the right one), understood each other, and their skill was thereby increased tenfold.

Like Michaux and Unica Zürn, Max Ernst and Leonora had identified themselves with animals, where Max Ernst played the role of a bird and Leonora became a horse, characters who were visualized in their paintings. Unlike Unica Zürn Leonora was a very skilled artist.

During Leonora's time in the mental hospital Max Ernst had finally been released from prison, but he found that his mistress was gone and their home inhabited by an unknown family. He stayed for a month in the village and began one of his masterpieces Europe After the Rain, where he by making use of the decalcomaniatechnique produced a devastated fairytale landscape and as so often before he transformed himself into a giant bird - Loplop. Within the painting Leonora is depicted as turning her back against him whils she is disappearing into the desolate landscape, wearing a top hat.

During the following years, Max Ernst was repeatedly depicting Leonora in his paintings, even though he had married the millionaire Peggy Guggenheim, who had made sure he was rescued to the US. The jealous Peggy, later stated that: "Leonora is the only woman Max has ever loved. Max was so crazy about Leonora that he could not hide it.”

Leonora's wealthy father, who she hated, sent her old nanny to the Santander asylum as part of a plan intended to get Leonora interned within a treatment center in South Africa. A friend of Picasso, the Mexican Renato Leduc, met Leonora in Madrid when she in her nanny´s company, and watched over by her father´s cronies, was on her way to South Africa. Leduc told her that if she managed to escape to the Mexican Consulate in Lisbon he would take care of her and provide safe conduct to his homeland. As we remember from the movie Casablanca, one of the main escape routes from Europe went through the neutral Portugal where Leonora ended up on her way to South Africa. She managed to shake off her father´s employees and reached the safety within the Mexican consulate, where she without being prepared for it encountered Peggy Guggenheim's entourage, which included the millionaire´s her former husband and his new wife, her children and pet dogs, as well as her future husband - Max Ernst.

Leonora and Ernst were still attracted to each other and although Max Ernst was ready to leave Peggy for Leonora, she did not want him to do it. Her grave crisis had meant a painful process of liberation and already when she fled France her friend Christina had tried to convince her that her attachment to Max Ernst was unsound, the full-fledged expression of a Oedipus complex. At the time, Freud continued to be the great guru for virtually every surrealist.

Leonora had brought Max Ernst's passport with her to Madrid and thought that as long as she could hold on to it he would be alive and come back to her. During her worsening madness, she tried to give away the passport to a hotel guest, but he refused to accept it:

This occurred in my room, where the man's eyes pained me to such a degree that he might as well have been stabbing needles into my eyes. When he refused to accept Max´s passport I remember I replied, "Oh! I understand, I have to kill him myself", in other words, I had to detach myself from Max.

In Lisbon, Leonora explained to Max Ernst that she still loved him, but according to Peggy Guggenheim, Leonora realized "that her life with Max was over because she could no longer be his slave, and it was the only way she could live with him”. Many years later Leonora explained:

There is always a dependency in a love relationship. And it can be very painful to be dependent. I think many women ... people really, but I say women because it is almost always women who are the most dependent ... have felt trapped, suppressed at times, by such a dependency. I mean not only a physical attachment arising from the fact that you are often supplied, but emotional dependency as well, and that you are becoming influenced by another person´s opinions.

Leonora married Renato Leduc and received Mexican citizenship. In Mexico, she became an appreciated artist. Nonetheless, it was during her three years with Max Ernst that her artistic ability and force began to blossom and the inferno that followed transformed her, like fire in alchemistic theory transforms other base matter into gold. Leonora Carrington had alchemical inclinations and her art and writing are filled with a kind of magical realism, like the one she used to transform a mental hospital into a wonderland; beyond good and evil.

Both Unica Zürn and Leonora Carrington lived in the shadow of dominant men. Unica went under, but Leonora survived the painful process of separation and liberation. We don´t know if she would have been happier, or more successful, if she had stayed with Max Ernst. Nevertheless, she became known as a forceful and original artist. When she in her in old age was reminded of her time with Max Ernst, she often became irritated. Leonora Carrington had become an independent woman and did not want that neither she, nor her art should be considered through a lens colored by Max Ernst's personality and actions. Frustrated by all the questions about her relationship with Max Ernst, she could exclaim: "That was three years of my life! Why do people not ask me about anything else? "

Zürn, Carrington and the fictional Hedda Gabler were during a time of their lives mad. They all lived within a man's world. Zürn and Carrington submitted themselves to the strong influence of men. Zürn went under, but Carrington survived. It can of course have depended on the kind of men they lived with and were inspired by. In Ernst's case, he was a seducer, but the women who got in his way rarely accused him of having abandoned them, instead they argued that he appreciated them and acted as an inspiration for their creativity. Ernst's last wife, Dorothea Tanning, was like Leonora Carrington much younger than he and like Leonora she was also a significant and independent artist and writer.

Unlike Zürn and Carrington Hedda Gabler fought against the men who surrounded her and tried to destroy them. For her, liberation seemed to be equivalent to power. Zürn chose submit to men, while Gabler manipulated them. However, compared to Zürn and Carrington, Gabler obviously lacked creative ability. She was unable to transform her life into a work of art, instead she tried to transform her environment according to her own measurements and requirements – reflected by her plea to Eilert Lövborg that he would "die in beauty".

Bellmer, Hans (2004) Little Anatomy of the Physical Unconscious, or The Anatomy of the Image. Waterbury VT: Dominion Press. Brandell, Gunnar (1979) Freud, a man of his century. Brighton: Harvester Press. Carrington. Leonora (1988) The house of fear : notes from Down below. New York: E.P. Dutton. Danchev, Alex (ed.) (2011) 100 Artists'Manifestos: From the Futurists to the Stuckists. London: Penguin Modern Classics. Koestler, Arthur (2006) Scum of the Earth. London: Eland. Land, Nick (1992) The Thirst for Annihilation: Georges Bataille and Virulent Nihilism London: Routledge. Meyer, Michael (2004) Ibsen. Stroud: History Press. Michaux, Henri (1968) The Selected Writings of Henri Michaux, trans. by Richard Ellmann. New York: New Directions. Miller, Henry (2005) Tropic of Cancer. New York: Harper Perrenial. Schneede, Uwe M. (1972) The Essential Max Ernst. London: Thames and Hudson. Suleiman, Susan Rubin (1993), “The Bird Superior Meets the Bride of the Wind: Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst,” in Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle de Courtivron (eds.) Significant Others: Creativity and Intimate Partnership. London: Thames and Hudson. Zürn, Unica (1994) Man of Jasmine and Other Texts: Impressions from a Mental Illness. London: Atlas Press.