ENIGMATIC HAITI comprehended through its gods and Duval Carrié

At the moment I find myself the Dominican Republic where Maslou, a Haitian who has lived and worked in the country for more than twenty years, is putting up tiles in our kitchen. It is a sad fact that Haitians are discriminated against in the Dominican Republic. Fleeing poverty and violence, they cross the border into the neighboring country where they are exploited while doing underpaid work and constantly run the risk of being captured by military and police and transported back across the border as illegal immigrants An activity that in the Dominican Republic has given rise to a multifaceted and difficult-to-investigate corruption that includes politicians, lawyers and police who profit at the expense of defenseless, impoverished Haitians.

My good friend Mats Lundahl recently wrote an article detailing the misery that Haiti is now suffering from during the absence of an effective government, while drug-financed mafia gangs run amok in its villages and cities.

On October 3, 2024, a Haitian gang of gangsters attacked the small town of Pont-Sondé, north of Port-au-Prince, killing at least 115 people, including women and children, and wounding at least 50. At least 45 houses and 34 cars were set on fire. Between November 13 and 16, more than 20,000 people were forced to leave their homes in the Capital as a result of gang attacks. On the 19th, Pétion-Ville, the richest suburb of Port-au-Prince, was attacked, but the police, with the help of the local population, managed to repel the attack and kill 28 gang members. Between December 6th and 11th, at least 207 innocent people, most of them over 60, were killed by gangsters in Wharf Jérémie, one of the worst slums in Port-au-Prince. They were shot and hacked to death with machetes and knives, set on fire and thrown into the sea. The gang leader had believed that they had used black magic to give his son a fatal illness. On December 7th, a citizen guard lynched more than 10 gang members in Petite Rivière de l’Artibonite. The response was not long in coming. Between December 8th and 11th, at least 70, perhaps over 100, people were murdered, including women and children. On the 16th and 17th, a gang attacked the Bernard Mevs Hospital with Molotov cocktails and set it on fire. On Christmas Eve, the Hôpital général, the largest hospital in Port-au-Prince, was attacked as it was about to reopen after being closed since February 2024 due to gang attacks. At least two journalists and a police officer were killed.

No airlines fly to Port-au-Prince anymore. The US aviation authorities have banned all flights there indefinitely. If you want to get from there to the only open airport, in Cap Haïtien, and out of the country, or vice versa, by helicopter it costs USD 2,500 and you are only allowed to bring 10 kilos of luggage. By early 2025, the number of people forced to leave their homes as a result of gang violence had reached over a million, out of a total population of just over 11.8 million. Et cetera, ad infinitum, ad nauseam.

All this on top of earthquakes, hurricanes, centuries of political oppression and catastrophic environmental degradation. Born as the world's first republic ruled by former slaves, Haiti has for more than two centuries suffered from the racist contempt of the outside world and an overpopulation originally caused by the 800,000 slaves imported by the French to their colony of Saint-Domingue (which later became Haiti). A country which tropical soils could not even then feed them all. On top of the misery, Haiti was forced to pay reparations until 1947, paying for taking possession of the “property” that their oppressors had usurped. And despite all this, Haitian culture still flourishes, in music, art and literature and not least in the country's distinctive religion, Vodoun.

A religion as serious as Christianity or Islam, and like them with its various variants, Vodounn only gained the status of a religion in 2003. Vodoun is polytheistic and syncretistic – and its unwritten theology is extremely complicated. It is an accepted fact that Vodoun was imported from West African kingdoms, but this is still not entirely correct. Vodoun certainly has elements of African religions, but influences include Christianity, Islam and other religious traditions, not least those that arose on the island of Hispaniola, which Haiti shares with the Dominican Republic. The Haitian slaves came from a very large geographical area, a territory that stretched from the Gulf of Guinea to Angola, and some of the spirits worshipped in Vodoun can be directly traced from there, but not all. The African components merged with European influences. However, the African presence is tangible. When a Haitian dies, he travels anba dlo nan Ginen, underwater to Guinea.

I think about this when I watch Maslou fixing the tiles and talk to him during his breaks. His ancestors travelled across the Atlantic, chained in stuffy ship holds. Millions died during that journey across the vast expanse of the sea and their bodies were thrown into the ocean. Those who survived brought their gods, their music and created a new, flourishing culture in the Caribbean.

Tiles? I recall that the Haitian artist Edouard Duval Carrié created a wall of tiles (it looks like tiles, but are in fact rectangles made of Plexiglas). Against a blood-red ground, entwined with flowering aquatic plants, slaves float who have been thrown into the sea from ships as worthless cargo. La Triste Histoire des Ambaglos, The Sad History of the Underwater Spirits, is a story of diaspora. About an involuntary migration across the sea and its eerily sad end. The artwork is also a reminder of how the memory of this tragedy lives on. The ties with Africa were torn apart, but reminiscences of the old continent and its gods survived in all the misery that followed. Death was not final. Life remained in recollections of the survivors. A new world was created on American soil. Roots from Africa were planted in American soil and sprouted anew. Trees, roots and water are constantly present in Edouard Duval Carrié's art.

Duval Carrié has also painted large portraits of Africans, who anemones in the depths of the ocean have merged with corals and sea. Perhaps they have been transformed into water spirits, or sea gods, which makes me think of Ariel's song in Shakespeare's The Tempest:

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Ding-dong.

Hark! now I hear them—Ding-dong, bell.

Several years ago, when my wife and I were both working for the UN, she as a permanent employee and I as a consultant, we visited a lady in her apartment somewhere in the United States. I don’t actually remember if it was in New York or somewhere in Florida. In any case we discussed her contribution to an arts and crafts institution in Guatemala. I don’t remember neither her, nor her apartment, but I do very clearly remember a rather large and strange painting that adorned one of her walls. It was painted in a half-naive, half-academic style and depicted a naked lady wading in a river, with a revolver in one hand, against a backdrop of lush jungle vegetation. That was the first time I had heard of Edouard Duval Carrié, born the same year as me – 1954. It annoys me that I never took a picture of that painting, especially since Duval Carrié’s art has since appeared in various contexts and steadily increased in value. His imaginative world is generally morbid and difficult to interpret, often with historical or Vodoun motifs.

For several years now, Duval Carrié has been living in Miami. Born and raised in Haiti until he, at the age of ten, with his parents was forced to flee the terror regime of “Papa Doc” Duvalier He has since lived in various places, such as Puerto Rico, New York, Montreal and Paris. Duval Carrié studied at the Université de Montréal and Loyola College in Canada, as well as the École nationale supérieure de beaux-arts in Paris, where he lived for several years, until he moved to Miami. On several occasions he has returned to Haiti, but under the current, terrible conditions, he cannot imagine settling there.

Like so many others who grew up in a distinctive environment, he has throughout his life carried with him his Haitian heritage, which since the time of slavery has been characterized by an enforced diaspora and/or isolation. A sense of rootlessness has simultaneously created a connection with the nature of the Caribbean island and the strange creatures who inhabit the mysterious, unbound world of Vodoun.

Duval Carrié is a cosmopolitan whose artistic sensibility leaves him open to the multitude of multifaceted identities that exist within the magical sphere of Vodoun He likes to portray himself and his figures as beings that, like trees, have roots deep in the earth and sea and a crown that opens up to an infinite universe. For example, he has depicted “my life as a tree” and represented it on plexiglass, with several other variants made on aluminium.

In recent years, Duval Carrié has increasingly worked with different materials and created large-format works and installations through which he has attempted to depict migration and transformations in an almost cosmic form, where African, Caribbean and European traditions speak to each other and blend together into spiritual constellations.

Vodoun as a spiritual dimension appears to be constantly present in Duval Carrié's artistic sphere. It often takes on a sacred character and several of his later works evoke associations with the stained-glass windows of Gothic cathedrals,

or altar cabinets,

like this altar dedicated to the sea god Agouwe:

In several of his oil paintings, Duval Carrié depicts religious Vodoun practices, such as the home altars with offerings that might be found in both Haitian and Dominican peasant homes. As in the painting below, where he has placed such an altar in the middle of a river within a tropical jungle, in full accordance with his constantly repeated associations with the life-giving powers of water and vegetation. In this case, the sacrificial table is surrounded by crocodiles, an allusion to the nocturnal Vodoun rites in Bois Caïman. The Forest of Crocodiles, which on August 14th, 1791, gave the start to the nationwide slave revolt that ended in 1804 with Haiti's liberation from France. In the lush jungle, crocodiles lurk, barely visible.

The day after the ceremony in Bois Caïman, signal drums thundered across the French colony and the rebellious slaves set fire to the sugar plantations. Smoke could be seen as far as Louisiana in the United States.

Sugar, the Devil’s crop, is one of many reasons for Haiti’s seemingly eternal curse. Sugar cultivation can be traced back to around 6,000 BC, when sugarcane was harvested in New Guinea. The earliest known large-scale production of crystalline sugar took place in northern India, around 3,000 BC. After being a rare commodity in Europe, sugar became widely known in the late Middle Ages and its use spread as sugar became an increasingly cheap and accessible product. Combined with other tropical commodities – coffee and tobacco – sugar became an important, invigorating stimulant for Europe’s growing number of industrial workers, along with the increasingly popular rum. Today, sugarcane is the third most valuable crop after cereals and rice. Sugar plantations cover 26,945,000 hectares in 110 countries. Between 2019 and 2020 alone, 167 million tons of sugar were produced (some of which comes from beets), while a dozen countries use at least 25 percent of their arable land for sugar cultivation. Sugarcane is used to produce at least 80 percent of the sugar consumed by the world's population.

.

.

Sugarcane grows to a height of 2 to 6 metres with strong, fibrous stems. It is some sort of overgrown grass and generally covers large areas. The often very extensive sugar fields tend to be home to a variety of pests, some of them poisonous, and so are the pesticides used to protect the crops. In addition, sugar has proven to be a harmful food that most of us can actually do without.

Most sugarcane is still harvested by hand, and sugarcane cutters die from their hard work. For example, it was estimated that in the past two decades at least 20,000 people have died from chronic kidney disease in Central America, most of them sugarcane workers along the Pacific coast. This may be due to working long hours in tropical heat, without adequate fluid intake, and constantly being subjected to physical ailments caused by hour after hour of repetitive movements. If this is the case today, it is not difficult to imagine the torture endured by the whipped, unpaid slaves in French Saint-Domingue. The French slavers were well aware that the machetes their slaves used to cut their sugar cane just as well be used as weapons against them and their families, which was ultimately the case. What could be expected of 800,000 people who were used as livestock, killed, tortured and despised?

Throughout history, sugar has been a major economic and social influence, driving the expansion of European empires. The “white gold” fueled the Atlantic world’s lucrative trade in people, gunpowder, cloth, sugar, and rum, creating a great wealth for a privileged few. Sugar’s dark history, apart from being a noxious food, has deep roots in the slave labor that was perpetuated by the enormous demand for sugar cultivation in Brazil and on Caribbean plantations. As a result, between 1501 and 1867, over twelve million Africans were shipped to the Americas, under appalling conditions. These twelve million were the ones who survived the Atlantic crossing, which cost at least half as many lives.

Duval Carrié has created a large “sugar ship” that seems to be afloat, glittering and seductively above the viewer’s head, like a constellation of stars. At the same time, there is something lugubrious and threatening about the insect-like construction.

In a diptych, Duval-Carrié depicts how Death, with the help of the French, brings his cargo of slaves to Saint-Domingue’s shores, only to reap the French as victims of his own disgusting trade in human being and the inhumane treatment of their slaves.

It was not only the bodies of Africans that were brought across the Atlantic; their thoughts, religion and art were also rooted in the Caribbean soil, where they grew mighty and strong. As migrants have done over the millennia, the religion of the slaves was mixed with other influences. Elements from the beliefs of a variety of different peoples were joined together – contributions from West Africans such as Bambara, Fon, Fulani, Ashanti, Yoruba, Ovimbundo, Kimbundo, Bakongo, Lunda, Chokwe and many more. Several slave traders tried to mix their human goods so that the language barrier made conspiracies and rebellions more difficult. However, there were also elements from folk religions in a variety of places other than the African mainland – traditions were brought by Guanches from the Canary Islands, from Irish, Gypsies, Portuguese, Andalusians, Moors from North Africa and the Levant, Jews, Scots, Irish, and not least the indigenous inhabitants of the islands – Caribs and Tainos. Nevertheless, most powerful were the old gods from kingdoms such as Mali, Dahomey and Ashanti, and those positioned further south – like Congo and Luanda.

A syncretism that makes me think of Neil Gaiman's novel American Gods, which tells how immigrants from all corners of the world brought their gods with them to the United States, but over there they forgot to show them their worship. However, all these neglected gods are still alive and maintain some contact with each other, while they live among common people, but are now forced to work as undertakers, butchers, taxi drivers, prostitutes, petty gangsters, or large and small business owners. They fight against the "new gods" who reside within the modern technocratic world, with its entertainment industry, stock trading, big capital, internet and drug trafficking.

However, within the realm of Haitian Vodoun, the old gods survive, along with a variety of other natural beings. They do not always live in harmony with each other, and Duval Carrié occasionally depicts how armed, strange creatures confront each other in a Haitian, mythical jungle landscape.

The distinction between historical and modern realities can be dissolved in Duval Carrié's art, as well as in magical and everyday realms. In one image he seems to comment on the sadly divided and often bloody division between the nations that divide the island of Hispaniola, well aware that the two countries share a spiritual, folk-religious sphere. Two spirit beings stand facing the viewer – a burning figure by ruined trees on the left/west side of a river flowing from a common source and, on the right/east side another, spotted being, flanked by two palm trees. Below the spotted figure, a truck is seen dumping something towards the west side of the river, where a woman appears to be picking something up.

A difficult-to-interpret image, which I perceive from the viewpoint of my own world of imagination. The burning man might then represent the landscape of Haiti, deployed by overproduction, overpopulation, drought and other environmental disasters. Where people are forced to burn the few trees that remain yp obtain charcoal to heat their food and earn a meagre income, and who through their poverty are forced to opportunities for survival seek within a neighbouring country where they are ruthlessly exploited as underpaid labour. The spotted figure can then be considered as a representative of the Dominican population who have been infected by the plague of racism and also suffered from a lack of identity that caused them to deny their African roots and believe themselves to be pure-blooded descendants of Spaniards, who, in contrast to what they present as an underdeveloped Haiti, consider themselves as representatives for Western civilization and progressive spirit

.

.

The river that separates the spirit figures may then allude to the border river Rio Massacre, which through its name brings to mind the so-called Perejil Massacre that took place in October 1937. A mass murder of Haitians living along the northwestern frontier of the Dominican Republic and in certain parts of the nearby Cibao region. The massacre was initiated on the direct orders of the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo and carried out by army troops gathered from different parts of the country. The well-planned and sudden massacre killed practically the entire Haitian population living by the Dominican border and only a few managed to escape into Haiti. The massacre got its name because the perpetrators often held up a bunch of parsley – perejil – asking their intended victims what it was, if they then pronounced the word with a hard r, it was considered as a sign that they spoke Creole and therefore were Haitians. Skin colour played less of a role, as many Dominicans were as dark-skinned as their Haitian neighbours. The massacre claimed the lives of an estimated 14,000 to 40,000 men, women, and children.

It is entirely appropriate that Duval Carrié also portrays the “Dominican” as a spirit being. Dominican folklore contains a variety of magic/naturel creatures, and the country also has a form of Vodoun with its own distinctive features and its own lwas, gods who generally are called misterios in the Dominican Republic.

The Dominican author Marcio Veloz Maggiolo wrote a novel that appears to be acted out in the same mystical realm as Duval Carrié’s art. The immortal protagonist of Biografia diffusa de Sombra Catañeda, the Diffuse Biography of Sombra Catañeda, appears to be a descendant of the island’s first conquistadors and tells its story out of the realm of lwas and misterios.

Sombra Catañeda asks us if today'sople are not the product of yesterday, subjected to constant mutations in an existence that is far from logical and understandable. The history that people tell each other is arranged and falsified by fabulists, politicians and historians, all with a highly personal agenda. The truth is found within the magical/spiritual sphere within which Sombra Catañeda resides and from which he observes the inhabitants of the island shared by Haiti and the Dominican Republic. He tells of its historical development, from the time when the Taínos arrived in their canoes to the island that they possibly called Quisqueya, until the day Veloz Maggiolo wrote his book (i.e. 1981, he died in COVID 2021).

Sombra Catañeda's story may seem like randomly assembled history, which over centuries moves within a sphere of abandonment and division. He seems to be both sender and receiver, an unintentional actor, hero and villain. Superhuman and human – all too human.

In Duval Carrié's work present and past are mixed together as well and the union seems to take place in his Vodoun-inspired spirit world. For example, an image which I assumed represented the sea god Agwé (or Agouwe), who is often depicted as an admiral, has the for me confusing title Capitaine Tonerre.

Eventually I found out that El Capitán Trueno (Captain Thunder) was the hero of a series of Spanish comic books created in 1956. The series was published continuously between 1956 and 1968 and became the most popular Spanish superhero comics of all time. At its peak, it sold more than 170,000 copies per week and was translated into French, which is probably how the young Duval Carrié became fascinated by it. The comics were inspired by Hal Foster's Prince Valiant, the nobleman from Thule who became one of the knights of King Arthur's Round Table. El Capitán Trueno was, like Valiant, a knight-errant who encountered adventures all over the world, although he moved in the 13th century and not like Valiant in the 5th century, while Duval Carrié's Capitaine Tonerre is dressed like an aristocrat from the 18th century.

On January 12, 2010, Haiti was struck by a catastrophic earthquake, the epicentre was about 25 kilometres northwest of Port-au-Prince. In the two weeks that followed, the country was hit by more than 52 aftershocks. Three million people were directly affected by the devastation and an estimated 100,000 to 160,000 men, women, and children died.

Communications systems, air-, land-, and sea transportation facilities, hospitals, and electrical networks were severely damaged, hampering rescue and relief efforts. Port-au-Prince’s morgues were overwhelmed with tens of thousands of bodies. Rescue efforts were hindered by mainly unfounded rumours that violence and looting had paralyzed the Capital. Before relief efforts could begin, the United States sent in troops to “maintain order.” In fact, there were significantly fewer violent crimes in Port-au-Prince after the earthquake than before. People worked intensively to rescue their neighbours and others from the rubble, and hundreds of people walked through the streets, singing and clapping their hands to calm all those who had lost loved ones, or who had been seriously injured by the rubble. As so often in Haiti's history, the disaster had an impact on art and culture. For example, a Haitian-American journalist and aid worker, Dimitry Elias Léger, wrote an interesting novel, God loves Haiti, told in a magical realist style with obvious inspiration from Márquez, Bolaño, Camus and Dante.

The prejudices that delayed international aid efforts and the disrespect for Haitian identity and culture are probably behind Duval Carrié's painting Erzulie Detained, in which we see the Vodoun goddess of beauty Èrzulie Fréda Dahomey, the lwa who oversees beauty, dance, luxury, flowers and joy, walking down the gangway of a warship, watched by two men armed with rifles and wearing red cross helmets. Èrzulie is equated with the Mater Dolorosa of Catholicism, who in the oil prints that often adorn Vodoun altars is depicted with a sword through her heart, while she is surrounded by votive offerings, interpreted by Vodounists as the jewellery, gold and precious stones that the coquettish Èrzulie is so fond of.

In Duval Carrié's painting, we see the sword of Mater Dolorosa within Èrzulie's halo and, like Mater Dolorosa, her face is marked by sadness and despair, caused by her empathy with the tormented people of Haiti, who were affected by both the earthquake as well as the impudence and insensitivity of outsiders.

In Duval Carrié's work, the goddess of love, Èrzulie Fréda of Dahomey, a[[ears as a guarantor of empathy and thus justice. In a painting on glass, he has depicted her as a personification of Justicia.

A representation that makes me associate it with the armed angels in Bolivian art.

While Duval Carrié's technique of depicting his divine world on glass makes me remember the beautiful paintings on glass I came across in Senegalese markets.

The lwas of Voudon can manifest themselves within the four elements: air, earth, water and fire. Èrzulie Fréda Dahomey is a Rada deity and as such she manifests herself, like water nymphs, within the element of water, which means she is considered to be gentle, loving and cool, although she can nevertheless be seized by jealousy and outbursts of anger, the latter due to her habit of always getting her way and being spoiled by those who are devoted to her. The usually calm and unwavering Rada lwas who are generally believed to have a West African origin, have their autochthonous counterpart in the Petro lwas, who are of Haitian origin and considered to be fierce, fickle and hot-tempered, their element is of course fire.

Èrzulie can also take the form of a Petro lwa, and she is then, if possible, more powerful than the gentle Èrzulie Fréda Dahomey. As Èrzulie Dantòr she is the undisputed queen of the ferocious Petros and mother of their founder and father figure Ti Jean Petro. Èrzulie Dantòr is unlike the mulatto Èrzulie Fréda Dahomey a formidable and powerful black woman, a solid and unwavering protector of women, children, and the outcasts of society. Unlike Èrzuli Fréda who bestows you with material riches, Èrzulie Dantòr blesses you with spiritual knowledge, needed to navigate through the miseries of everyday life. Èrzulie Dantòr's wealth endures and might be passed down from one generation to another, while Èrzulie Freda's more ephemeral gifts might disappear after a night

Èrzulie Dantòr is connected to the elements of both fire and earth. She is familiar with the powers of darkness, something that is depicted in Duval Carrié's painting Erzulie's Bath. In an underground cave, Èrzulie is about to descend into a pitch-black spring. She is surrounded by underground divinities, both those representing vegetation and those connected with Death. In the foreground we see Baron Samedi, god of the dead, and above the cave's stalactites we discern Erzulie's flowers and are thus reminded of the connection between the sinister underground powers to both death and the vegetation that sprouts from the black soil. It is not for nothing that the Hades/Pluto of ancient Greeks and Romans was the lord of death and the underworld, as well as vegetation and fertility.

Èrzulie's cave reminds me of my time among Dominican peasants who taught me that the Tainos were once lords of the entire island. However, when they and their gods were persecuted and abused by the Spanish conquerors they retreated to the underworld, from where they now secretly rule the island of Quisqueya/Hispaniola. You can encounter their spirits in caves where you find the saints, represented by stalactites and stalagmites. The power of the Indians springs forth in rivers and springs, and in the Dominican Republic (and I suppose also in Haiti) it is customary to offer sparkling things and sweets to the Indian spirits who dwell in streams and springs.

Like other deities in the Voudon Pantheon, the lord of the underworld, Baron Samedi, is endowed with a complex character and he manifests himself through a variety of appearances, often with different names such as Baron Cimetière, Baron la Croix, or Baron Criminel. As a god of death, Baron Samedi is generally depicted as an undertaker, dressed in a black tailcoat with a top hat, but as a living corpse he can also be depicted as a skeleton, or a cadaver prepared for his burial, which is why he may have cotton plugs in his nostrils and dark glasses to hide his lifeless eyes, or in the case of his manifestation as a Petro – glowing gaze. He can also be depicted as a youthful, virile and young man, with lively movements and a face painted like a white mask, or with only one half of his face painted white. As the god of death, Baron Samedi is the lord of both white and black people. His movements and speech may also be tinged with a certain “femininity”, since he like Death is both male and female. His voice is a nasal drawl.

As Death, Baron Samedi has no regard for politically correct beghaviour or lacks any kind of inhibitions, he is completely unpredictable. This makes him cynical and endowed with a merciless, often scabrous humor, facilitated by his divine ability to read the thoughts of people and other ceratures. Baron Samedi is thoroughly informed about everything that happens, in both the world of the dead and the one of the living. He lacks morals and can be capriciously cruel, while at the same time he can show empathy and some good sides. Baron Samedi is fond of rum and cigars and likes to eat apples, but like Death his appetite is unlimited and he eats large quantities of everything possible. Baron Samedi is also an incorrigible womanizer ablde to display a lot of charm and also act as a liberated and amusing homosexual man, not unlike a drag artist or the greasy cynical emcee in Cabaret.

Baron Samedi is married to Maman Brigitte, who in every respect is a female counterpart to her husband and who in her relationship with hers and her husband's subjects – les Guedes, often behaves as if she was a benevolent brothel madame.

Baron Samedi has many strings to his lyre and as the all-powerful Death he can appear as a cosmic figure and as such he is sometimes portrayed by Duval Carrié.

Duval Carrié may also allude to Baron Samedi's fertility aspects by depicting him as covered with leaves or other vegetation, often in the company of water spirits and other vegetation deities.

In his manifestation as Papa Guede, Baron Samedi is considered to be a fairly empathetic personality. As a caring psychopomp he accompanies the spirits of the deceased to the underworld and when a child is terminally ill, its parents ask Papa Guede to spare it, or at least give it a painless death. Papa Guede can also, if it occurs to him, unexpectedly grant that people who are close to death suddenly recover, or get out of a situation that may seem fatal. However, Baron Samedi can also behave like a ruthless mafia boss, someone who only acts for his own gain. He is then Baron Criminel and uses his Guedes as blackmailers and murderers. In that capacity, Baron Samedi is also a bokor, an evil sorcerer who relatives of murder victims, or others who assume that they have been wronged, can ask to exact revenge. As Baron Criminel, Baron Samedi can also appear as a ruthless capitalist, or as an imperialist like the United States, which has occasionally interfered with Haiti's internal affairs by force. Duval Carrié has depicted Baron Criminel in what looks like the bow of a warship, wearing his top hat, prolonged like stove pipe hat it might evoke associations with Abraham Lincoln's, or Uncle Sam's headdress.

Similar associations may be evoked by an enigmatic painting in which Duval Carrié depicts a youthful, white-clad, giant figure standing on a warship being towed by wolf-like creatures onto a river through a Haitian mangrove swamp

Haitian history is ever-present in Duval Carrié’s art. With a persistence reminiscent of Andy Warhol's repeated Marilyn Monroe portraits, he has created a variety of portraits of Haiti's great revolutionary hero Toussaint Louverture, who, born a slave and later freed, became the most prominent leader of the Haitian revolution. Throughout his life, Louverture fought for the liberation of slaves. In 1792, he wrote to the French National Assembly:

We are black, it is true, but tell us, gentlemen, you who are so judicious, what is the law that says that the black man must belong to and be the property of the white man? Certainly, you will not be able to make us see where that exists, if it is not in your imaginations—always ready to form new phantasms so long as they are to your advantage. Yes, gentlemen, we are free like you, and it is only by your avarice and our ignorance that anyone is still held in slavery up to this day, and we can neither see nor find the right that you pretend to have over us, nor anything that could prove it to us, set down on the earth like you, all being children of the same father created in the same image. We are your equals then, by natural right, and if nature pleases itself to diversify colours within the human race, it is not a crime to be born black, nor an advantage to be white.

To achieve and guarantee the freedom of the slaves, Louverture first allied himself with Spanish forces in his fight against the royalists of Saint-Domingue. After the French Revolution overthrew the monarchy, he supported Republican France, which had abolished slavery, and he thus became Governor-General of Saint-Domingue, but when Napoleon Bonaparte reintroduced slavery, Louverture's troops fought against Bonaparte's army.

As a revolutionary leader, Louverture proved to be an unusually capable military - and political man. He helped transform the desperate slave revolt into a purposeful revolutionary movement, with disciplined troops and an economically minded policy. Among other things, he negotiated a trade agreement with Britain and the United States.

Louverture's end was tragic. Misled by fraudulent guarantees, he was lured into negotiations with the French, but was immediately arrested and taken to France, where he was imprisoned in a fortress in the town of Doubs by the slopes of the Alps. While Louverture was still alive, the English poet William Wordsworth wrote a beautiful poem in his honour:

TOUSSAINT, the most unhappy man of men!

Whether the whistling Rustic tend his plough

Within thy hearing, or thy head be now

Pillowed in some deep dungeon's earless den;--

O miserable Chieftain! where and when

Wilt thou find patience? Yet die not; do thou

Wear rather in thy bonds a cheerful brow:

Though fallen thyself, never to rise again,

Live, and take comfort. Thou hast left behind

Powers that will work for thee; air, earth, and skies;

There's not a breathing of the common wind

That will forget thee; thou hast great allies;

Thy friends are exultations, agonies,

And love, and man's unconquerable mind.

By the time Wordsworth's poem was published, Toussaint Louverture was already dead, huddled by the cell's fireplace, its fading glow, having either died of cold and malnutrition, or tuberculosis.

Based on a contemporary engraving, Duval Carrié created a number of portraits of the revolutionary hero. Below is a selection from a much larger production.

Duval Carrié has also made other paintings depicting Louverture and his efforts. In one painting, a barefoot Toussaint appears seated on a red horse (the colour of the Petro spirits?). In his right hand he has a snake (the virtuous god Damballah, or the deadly green mamba?).

Other mounted personages from the Haitian Revolution appear in Duval Carrié's artwork. A pale Sonthonax rides a yellow horse through a desolate landscape. In one hand he holds up a document. It is probably his own declaration of the emancipation of the slaves.

Léger-Félicité Sonthonax was a French revolutionary commissar and de facto supreme leader of Saint-Domingue's white slave owners, who deeply disliked him, especially after his proclamation of the emancipation of the slaves. One of Sonthonax's most important tasks was to organize the army of Saint-Domingue so it would be able defend the island against attacks by British troops, while large parts of the French colony were already in the hands of rebellious slaves. In order to recruit soldiers and in recognition of the slave revolt of 1791, Sonthonax demanded that his newly formed army had to include black soldiers, and he did accordingly try to convince the French National Assembly that slavery must end immediately. As part of his efforts, while waiting for such a decree, Sonthonax saw to it that slavery was abolished in the northern parts of the colony. However, his critics, argued that Sonthonax's actions were based on his own desire for power, which is doubtful, since Sonthonax seems to have been a convinced abolitionist.

The fact that Sonthonax in Duval Carrié's painting rides alone, without any companion, may be because he found that former slaves were hesitant to join his troops. Several of them had already been recruited by Toussaint Louverture, and other revolutionary leaders. Other slaves worried about what would happen if the National Assembly refused to approve Sonthonax's proposal to end slavery and that the white slave owners would then vent their anger in the form of increased violence and bloodshed. White plantation owners had begun to flee the country, but several mulattoes and freed slaves who had also been slave owners opposed Sonthonax. It was only when the French National Assembly ratified the Declaration of Emancipation in May 1794 that Toussaint Louverture and his army of well-disciplined, battle-hardened ex-slaves joined Sonthonax's army.

Toussaint soon became the undisputed leader of the colony, although he was actually the representative of the French General Assembly. Louverture was troubled by Sonthonax's presence and his interference in the policies and reforms that the black general was trying to implement. In 1797, he appointed Sonthonax as his representative to the General Assembly, but when the latter hesitated, Louverture placed him under armed escort and put him on a ship bound for France

When Duval Carrié in one of his paintings depicts the Republican Army as a group of well-uniformed dolls on pedestals, it is possible that he is alluding to the faltering strength of Sonthonax's army, before Louverture gained the upper hand and control. Blacks, mulattoes and whites seem equally uncertain in their roles and this toy army could probably have been easily defeated by British or Spanish forces.

Duval Carrié's rigid tin soldiers remind me of Fernando Botero's stuffed, doll-like military juntas, which also display soldiers of various sizes

And the step from there may not be that far to the corrupt military and tonton macoutes (militia/secret police) who have supported Haiti's dictators and who are here handing over a plastic-wrapped cake to one of their top leaders.

Oppression and lurid spectacles have sometimes gone hand in hand in Haiti, where a self-absorbed elite has often stolen most of the pie that should have been equally shared among the Haitian people. A culmination of this abuse of power was the Duvalier family, with its notorious dictators; father and son – Papa - and Baby Doc.

The dubious tradition of exalting and enriching oneself at the expense of others while at the same time trying to found a dynasty by leaving power to one's son, began early in Haiti's history. One of Louverture's most capable generals, Henri Christophe, founded in 1811 the Kingdom of Haiti in the northern part of the country, with himself as King Henri I and his son Jacques-Victor Henry as crown prince. King Henri I imposed a strict regime and corvée, a form of forced labor that bordered on slavery. Against all odds, Henri I managed to reconstruct the previously significant income from agriculture, and especially sugar production. The improved economy allowed the construction of an impressive citadel and several palaces. However, the kingdom's economy collapsed after ten years, and when a revolution broke out in 1820 Henri Christophe committed suicide. The rise and fall of the Haitian king are depicted in the Cuban author Alejo Carpentier's novel The Kingdom of This World, which since its publication in 1949 has been hailed as an early example of Latin American "magical realism".

Despite his despotic tendencies, Henri I saw it as his duty to make Haitians demonstrate their true potential to the outside world and considered his heavy-handed methods of increasing the Kingdom's revenues as a temporary, but necessary evil. Illiterate himself, Henri I saw public, compulsory and free education as a means of combating racial prejudice and an opportunity to present an enlightened black nation to the world.

He collaborated with the English abolitionists William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson. Wilberforce recruited British teachers and missionaries on Henri I's behalf, who would assist him in his educational efforts. Among them was the artist Richard Evans, who would assist with the education of Crown Prince Jacques-Victor. During his time at the court of Jean Christophe, Evans painted two portraits, one of King Henri I and one of his son.

It is possible that Duval Carrié was thinking of Henri Christophe when he made a painting that he called King Louis, depicting a masked man with a perruque allongée, lifting a palace above his head. If the image could be applied to Henri Christophe, I could imagine that it alludes to Haitian and/or African potentates who, in disrespect for their own origins and the culture of their country, hide behind a white mask of “success” and “development” and thereby adopt the pretensions and prestige-seeking of foreign powers.

Duval Carrié and his family were forced to flee the terror of Papa Doc Duvalier. If a ruler like Henri I tried to turn his back on his nation's traditions and convert his nationals to adherents of English Protestantism, the physician dictator Papa Doc instead sought to exploit Vodoun mythology to instill fear in his people. Like Baron Samedi, Papa Doc preferred to dress entirely in black, while speaking with the same well-balanced nasal accent as the god of death. His militia/secret police, the feared Tontons Macoutes, wore black glasses, just like Baron Samedi's subjects, the Guedes.

In his attempts to intimidate and suppress all political opposition, Duvalier gave the Tontons Macoutes free rein to carry out systematic violence, terrorism, and human rights abuses. Under Duvalier, the Tontons Macoutes killed an estimated 30,000 to 60,000 Haitians.

These special forces were originally called the Volontaires de la Sécurité Nationale, National Security Volunteers. Their popular name was derived from a scary figure used to scare children. Uncle Burlap was a monster who roamed the streets at night, seeking out disobedient children, whom he stuffed into his sack and then took home to eat. The Tontons Macoutes wore straw hats, or blue safari hats, red scarves, dark blue denim, and the indispensable black glasses. In his 1966 novel The Comedians, Graham Greene painted a frightening and comical picture of Haiti during Papa Doc's reign of terror.

In his painting Parade of Grimaces, Duval Carrié seems to make a direct allusion to King Henri I's heir Jacques-Victor. Baby Doc – Jean Claude Duvalier – is dressed in an eighteenth-century costume while his father, Papa Doc, in the guise of Baron Samedi, with his black-and-white face, places one hand on his son's shoulder. The mother/Maman Brigitte stands on the son's other side. Papa Doc's wife, Simone Ovide Duvalier, also tried to appear to the public as if she, like her husband, was a Vodoun expert.

Also in the picture are two of Baby Doc's three sisters and representatives of the church and the army. Baby Doc has a white pacifier in his mouth, a hint that even if he was, through his father's provision and a changed constitution, was provided "absolute powers", he largely let the country be ruled by his dominant mother and, at first, Luckner Cambronne, his father's Minister of the Interior and leader of the Tonton Macoutes. Like so many other ruthless potentates, Cambronne preyed on poor people. In his case, he made a fortune on the basis of the few raw materials the country had to offer – its people. Through his agency, five tons of blood plasma were exported every month. However, Madame Ovide soon tired of Cambronne, who was widely considered to be her lover, forced him into exile and replaced him with Roger Lafontant, also a leader of the Tonton Macoute.

After Baby Doc came to power in 1971, he made some minor, cosmetic changes to his father's regime, but soon delegated most of his power to his mother and her advisors. During his dictatorship, Baby Doc mostly stayed out of the public eye, enjoying his playboy lifestyle, with luxury cars and a keen interest in oriental martial arts and jazz. Meanwhile, state-sponsored violence continued, with thousands of Haitians tortured and killed, while hundreds of thousands fled the country.

However, in 1980 Baby Doc made an unexpected appearance when he had the State pay for his lavish wedding to Michèle Bennett, the daughter of Ernest Bennett, a Haitian businessman and descendant of King Henri Christophe. Ernest Bennett owned more than 20,000 hectares of land (an unusually large area in an overpopulated country with mainly depleted soils), where he grew coffee; more than 2,000 people worked for him. The daughter's marriage to the country's dictator proved to be unusually profitable for her father. Ernest Bennett's exports of coffee and cocoa increased significantly, he became the exclusive dealer of BMW and together with his brother Frantz, Ernest started a profitable drug transit trade. The brothers were arrested in Puerto Rico and served a three-year prison sentence for drug smuggling. Baby Doc and Michèle's wedding cost the State between 2 and 3 million US dollars and was widely considered a scandal in the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere.

Many hoped that the scandal surrounding the expensive spectacle would lead to the fall of the Duvalier regime and Duval Carrié's hopeful comment on the whole thing became a painting depicting Baby Doc, wearing a wedding dress, in the process of shooting himself in the head.

At the same time, Duval Carrié created a new and even more sombre version of his Parade of Grimaces, now with all three of Jean-Claude’s older sisters present. They had also entiched themselves through the terror regime and six years later fled the country with their little brother. The old demon Papa Doc was dead by then, but in the painting but he appears he once again appears as the immortal Baron Samedi.

Jean-Claude Duvalier had in vain asked his father to appoint his eldest sister, Marie-Denise, as successor. She was married to Max Dominique, former commander of the presidential guard. In 1967, Papa Doc had suspected that his son-in-law was behind a series of deadly explosions, including one in the presidential palace and one in the city’s casino. At the insistent pleas of his wife and daughter, Papa Doc, against all odds, pardoned Max Dominique, who after being forced to witness the execution of his fellow officers and friends was sent off as "inspector of the European embassies."

The main person behind the accusations against Max Dominique was certainly his main rival, the Minister of Tourism. Luc Albert Foucard, brother of Duvalier's private secretary and mistress, Yvon St. Victor, and married to the dictator’s second oldest daughter – Nicole. Her older sister Marie-Denise, who had been forced to Spain with her husband, was back after just one year and then replaced her father's dismissed secretary/mistress, Yvon St. Victor. Soon, the previously death sentenced Max Dominique was also back in the country. Papa Doc had by then had 19 officers executed whom he assumed were behind the coup attempt he previously had accused Max Dominique of. The youngest Duvalier-daughter, Simone, who in the painting is partially hidden behind her older sister, was not as scheming and involved in internal power struggles as her sisters, but was nevertheless just as greedy as the rest of her family.

However, the costs involved in Duvaliers' wedding were nothing compared to what happened when the Duvaliers fled after a popular uprising that finally took place in 1986. Below, Baby Doc, Michèle and Simone Ovide are seen fleeing to the international airport of Port-au-Prince airport, where a US military plane is waiting to take them to exile in France. Their exile, however, became difficult because they were in France constantly threatened by legal cases through which lawyers on behalf of the Haitian state demanded the return of the estimated USD 300 million that the Duvaliers had brought with them after robbing the Haitian people.

The notorious couple's theft of a considerable amount of money was, for example, revealed during a house search when the French police surprised Michèle trying to flush a quantity of papers down a toilet. It turned out to be receipts for clothes worth USD 168,780 purchased from Givenchy, USD 270,200 for jewellery from Boucheron and USD 9,752 for horse saddles from Hermès.

Despite this, the Haitian state failed to recover most of the stolen money and the couple, despite repeated attempts to have them extradited, were able to continue living in a castle in France; they were personal friends with Jacques Chirac.

After Michèle and Baby Doc divorced in 1990 (she was then living with a lover in Cannes) and she tried to settle in the United States, she had a fortune estimated at USD 130 million. The sum was calculated through the payments that Baby Doc guaranteed her in connection with their divorce in the Dominican Republic. Simone Ovide Duvalier died in 1997, Baby Doc in 2014, but Michèle still lives in Paris.

As an artist characterized by magical realism, Duval Carrié often portrays Haiti's hardships in the form of meaningful metaphors, often with vegetarian allusions. In Cotton, Gunboats and Petticoats, we see Haiti as a female figure wearing a wide, archaic dress, standing chained astride the Caribbean islands of Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico. Along the horizon, warships are patrolling the sea. Instead of a head, the dark-skinned lady has a tree which thorny branches, despite appearing dead, bear encapsulated flowers and leaves.

Duval Carrié repeats a similar theme in The Little Crippled Haiti, but here Haiti is a little girl with wooden legs and a crutch, placed in the middle of the Atlantic. Her head is now without any facial features, but consists of a tree from which branches bloom fantastic leaves, flowers, and multicoloured eye masks. In the background are stairs leading up to a blazing fire and what I believe to be a veve, one of the many symbols drawn on the ground in a Vodoun shrine to invoke the lwas. However, I don’t know what divinity Duval Carrié's veve might allude to (if there is one?).

It may actually appear to be somewhat strange that when Duval Carrié depicts his dream Haiti, he often creates a lush, tropical landscape, when in reality Haiti largely consists of over-cultivated lands scorched by tropical heat. A landscape that is masterfully depicted in Jacques Roumain's novel Masters of the Dew from 1944, for example in its introduction:

We will all die... — and she plunges her hand into the dust; old Delira Deliverance says: we are all going to die: the animals, the plants, the living Christians, O Jesus-Mary, Holy Virgin; and the dust flows between her fingers. The same dust that the wind blows back with a dry breath over the devastated field of millet, over the high barrier of cacti eaten away by verdigris, over the trees, those rusty bayahondes.

Roumain continues by depicting the parched earth as if it was the skin of an aging, black woman. I have met such women in both Haiti and the Dominican Republic, handsome but worn.

Beyond the bayahondes, a mist rises, where the half-erased outline of the distant hills is lost in a blurred pattern. The sky has not a crack. It is only a burning sheet of metal. Behind the house, the rounded hill resembles the head of a black woman with peppercorn hair: sparse brush in spaced clumps, close to the ground; further on, like a dark shoulder against the sky, another hill rises, crisscrossed by sparkling ravines: erosion has exposed long flows of rock: it has bled the earth to the bone.

It is as if Duval Carrié dreams that the Vodoun gods will once again fertilize the devastated lands of Haiti. In one image, the African gods are sailing in a boat with a palm tree as mast and sail. Above them floats Ayida Wedo, entwining her husband Damballah, the Rainbow Serpent. Ayida Wedo is the Lady of Heaven who conveys hidden knowledge to people. She is a fruitful and wise divinity who helps us avoiding mistakes and to travel in the right direction. The African gods sail across a green sea of fertility.

Perhaps they carry with them a hope that Haiti will once again come to life and flourish in all its tropical exuberance. In his picture Sower, Duval Carrié shows how a divinity, perhaps the farmer god Zaka with the red face of the Petro gods, spews his life-giving innards over the soil of Haiti.

The multi-coloured body of the Sower is found in the water deities that Duval Carrié often depicts, entirely in accordance with the beliefs about water deities found among farmers on both sides of the border dividing the island of Hispaniola. As an example, I have on several occasions visited the spring of La Agüita north of the Dominican town of Las Matas de Farfán. People told me that the spring is home to Anacaona, an Indian queen who retreated there after the Spanish exterminated the Tainos and took possession of their lands. However, it is not only Anacaona, who like Érzulie loves sparkling beautiful things, who seems to live in that spring. In her figure, Spanish water nymphs, the serpent god Damballah, the fertility-bringing child San Juan and several others are united in the shape of Anacaona, just as in Duval Carrié's representations of multi-figured water deities.

From my point of view, Duval Carrié seems to want to express that the arrival of African divinities to the island of Hispaniola was different from that of the Spanish conquistadores. More in harmony with the life and pretensions of the Taino. As in a painting where he makes Columbus's misguided and ostentatiously dressed company appear to the astonished Taino as if they were alien, exotically bedecked birds.

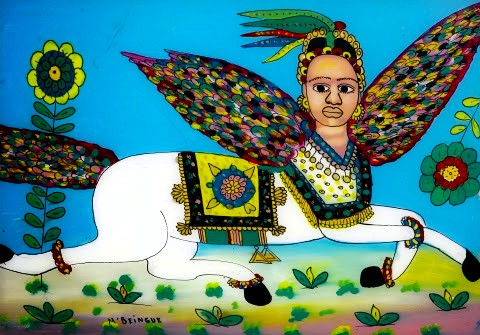

Something completely different from when Africa's strange, mythical creatures appeared on the island's shores.

This is not to say that Duval Carrié is unable to identify with strangers who have arrived from places other than Africa, becoming amazed by the people and landscapes of tropical regions. For example, he has been inspired by several of Martin Johnson Heade's tropical landscapes. Johnson Heade travelled, among other places, in the jungles of Central America and Brazil, from where he brought back to the United States paintings depicting exotic birds and flowers

Duval Carrié has by following Heade created several realistic detailed studies of tropical landscapes.

He has also created personal reworkings of several of Heade's more remarkable landscapes. For example, Heade made a painting he called Sunrise in Nicaragua. A landscape sparkling in the dew of dawn.

Duval Carrié reinterprets Heade's morning landscapes in a series of paintings in which he has preserved Heade's sparkling white spots, though his Heade interpretations are moonlit depictions "after Heade". As in the difficult-to-interpret painting below, where a shimmering black figure on a seashore appears in an equally sparkling, nocturnal landscape.

Occasionally, Duval Carrié seems to allude to different artistic traditions, both classical and modern. The chiselled, elaborate frames around several of his paintings bring to mind Indian miniatures.

And his Hindu Aesthetic appears to be reminiscent of the contemporary Italian "trans-avant-garde artist" Francesco Clemente's similarly difficult-to-interpret, Indian-inspired paintings.

Nevertheless, Duval Carrié’s art belongs primarily to Haiti that belongs, within a mythical Vodoun land, its lush vegetation and superhuman powers, manifesting themselves time and time again. We have previously met Ayida Wedo, the Lady of Heaven, and her husband Damballah also appears frequently in Duval Carrié's art. He is a benevolent prince, lives close to rivers and springs where he rules over their aquatic creatures. His colour is generally white or green and he generally appears as a huge snake.

The centre field of the Haitian flag is adorned with a palm tree, crowned by the Jacobin, red Phrygian cap and protected by two cannons above the motto "unity gives strength". In one of his paintings, Duval Carrié seems to allude to this palm tree of freedom and equality and by Duval Carrié it is entwined by Damballah

Like Toussaint, the war god Ogoun is mounted on the red horse of the Petro lwas. Like Damballah (the snake that sheds its skin) Ogoun represents revolution, change and freddom, something that is emphasized by the fact that he is surrounded by Haitian palm trees, entwined by Damballah. But if Damballah is always calm and balanced, Ogoun can prove to be both bloodthirsty and unpredictable.

Ogoun followed and assisted the slaves during their fierce struggles against their oppressors, but like the red-skinned Ares of the ancient Greeks, Ogoun could be seized by a hysterical, unreasonable anger, as when he led Jean-Jacques Dessalines in his furious battles, fuellureed by the betrayal of Toussaint Louverture. When Dessalines was asked about his hatred of the French, he could take off his shirt and show his back, which during his time as a plantation slave had been slashed by the whips of cruel overseers. In 1804, he ordered the massacre of the remaining French on the island, between 3 and 5,000 men, women and children were mercilessly and systematically killed. However, he exempted the Polish legionnaires sent by Napoleon to defeat Toussaint, but who had gone over to the side of the rebels, the German peasants who had not been slave owners were spared as well.

One of Duval Carrié's images of lwas, puzzled me for a while. It was a painting he had inscribed with the name Grand Bala. An archaically and sophisticatedly dressed young man, with a monocle and a cane. His lower body consisted of a mummy-like, wrapped tree trunk. However, I soon understood that it must be a portrayal of the Grand (big) Bwa (tree). A personification of the lwa tree, which in Haiti is called Mapou and in the Dominican Republic Ceiba. A mighty tree that in Vodoun mythology represent the sacred Tree of the Earth. Surely the same tree that appears in so many other of Duval Carrie's creations. It is the Tree of Life that connects the earth with the sky and keeps its roots deep down in the life-giving underworld. Grand Bwa is beautiful and strong. With his herbs and leaves he heals the sick. He is the incarnation of nature, the protector and giver of life to the ancestors. He is the greatest of all "mysteries". He knows everything and can through his healing leaves cure everything. Through his ancient, stout trunk and widely branched foliage he carries ancestors and lwas, through them he knows what heals and what kills. Among his branches, which reaches high up into Sky and Heaven, lives Damballah, the mighty serpent, who is father to us all.

Within a hounfour (Vodoun temple), the Grand Bwa is represented by the potomitan (central pillar) placed in the middle of the peristyle (dance floor) where “horses” possessed by lwas act out their predestined roles. The dancers are possessed by lwas believed to appear in the midst of the faithful, after descending along the potomitan, which can be a living tree, or a pillar of wood or cement, often decorated with symbols of the original couple – Ayida Wedo and Damballah, or wrapped with ribbons and fabrics representing different lwas.

Now, over to Duval Carrié's, in my opinion, most disturbing image, which for me represents much of the violence and oppression that continue to thrive in a Haiti which culture, like a living heart, lives and beats in the midst of all the misery. Papa Doc, with his doctor's bag and cane, stands next to Baron Criminel beside their despicable yield of violence and infamy – the tortured and murdered corpse of writer Jacques Stephen Alexis, who, on Papa Doc's advice and in his presence, has been killed in one of Port-au-Prince's prisons. Like the crucified Christ, the writer's hands have been nailed to the floor, while his ripped out heart has been pierced by nails.

Stephen Alexis was a communist, novelist, poet and activist who courageously fought against the Duvalier regime of terror. He is best known for his novel Compère Général Soleil, My Brother General Sun, from 1955. After completing medical training in Paris, Alexis travelled through Europe and lived for a few years in Cuba. In April 1961, he returned to Haiti, shortly afterwards he was arrested and taken to Fort Dimanche in Port-au-Prince where he met with Papa Doc Duvalier, after which he was never seen again.

Compère Général Soleil tells the story of the journey of an impoverished, unskilled worker named Hilarion, from the prisons of Port-au-Prince to the sugar fields of the Dominican Republic and a death at the hands of the dictator Trujillo's bloodthirsty henchmen. In prison, where Hilarion had ended up after stealing a wallet, Hilarion meets the writer Pierre Roumel (a thinly veiled portrait of Jaques Roumain) who enlightens him about the Marxist view of life. Here the novel becomes somewhat too didactic. Like his American counterparts, the excellent writers Richard Wright and Ralph Waldo Ellison, Alexis was early on caught up in the communist movement, but unlike his American fellow writers, he never had time to become disappointed by their totalitarian behaviour and cynical exploitation of the blacks' violent desire for freedom.

However, the novel gains speed and depth in its depictions of Hilarion's further fate. He meets Claire-Heureuse and they start living together. Hilarion works with sisal processing and mahogany polishing, while Claire-Heureuse establishes a colmado, a small bar/grocery store. However, they lose everything after a criminal gang sets fire to their store. Like so many destitute Haitians, they leave their country and submit to the inhumane toil in te sugar fields of the Dominican Republic, where they becpme drawn into a strike that makes them being forced to flee back towards the Haitian border, where they encounter the dictator Trujillo's abominable Perejil massacres. When he and Claire-Heureuse try to get across Rio Massacre, Hilarion is mortally wounded. While dying, he asks Claire-Heureuse to remarry and, together with her husband, fight for a Haiti where people can live in dignity and peace.

An unfulfilled hope that has not yet come true, but which lives on with full force in the unique art of Duval Carrié, and a host of other Haitian artists and writers

Alexis, Jacques Stephen (1999) General Sun, My Brother. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. Carpentier, Alejo (1975) The Kingdom of this World. London: Penguin Modern Classics. Diedrich, Bernard and Al Burt (1970) Papa Doc: Haiti & and Its Dictator. London: Bodley Head. Dubois, Laurent (2012) A Colony of Citizens: Revolution and Slave Emancipation in the French Caribbean, 1787-1804. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. Duval Carrié, Eduard, Homepage https://duval-carrie.com/ Farmer, Paul (2012) Haiti After the Earthquake. New York: Public Affairs. Gaiman, Neil (2017) American Gods. New York William Morrow. Greene, Graham (2005) The Comedians. London: Penguin Modern Classics. Hebblethwaite, Benjamin (2021). A Transatlantic History of Haitian Vodoun: Rasin Figuier, Rasin Bwa Kayiman, and the Rada and Gede Rites. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. Hurbon, Laënnec (1995) Voodo: Truth and Fantasy. London: Thames & Hudson. James, C.L.R. (1989) Black Jacobins. New York: Vintage Books. Léger, Dimitry Elias (2015) God Loves Haiti. La Porte, IN: Amistad. Lemoine, Maurice (1985) Bitter Sugar. London: Zed Books. Lundius, Jan and Lundahl, Mats (2000) Peasants and Religion; A Socioeconomic Study of Dios Olivorio and the Palma Sola Religion in the Dominican Republic. London: Routledge. Lundahl. Mats (2025) ”Ett annat Haiti”, Svensk tidskrift, 17 januari. Price, Rod (1985) Haiti: Family Business. London: Latin American Bureau. Roumain, Jacques (1978) Masters of the Dew. Oxford: Heineman. Veloz Maggiolo, Marcio (2005) La biografía difusa de Sombra Castañeda. Madrid: Ediciones Siruela. Wordsworth, William (1994) Selected Poems. London: Penguin Classics. Yudkin, John (2012) Pure, White and Deadly. London: Penguin Books.