ROSSO FIORENTINO: Fury and pain of a Mannerist

Two years ago I and Rose visited Jackie and Joe, good and generous friends from New York. They had rented a villa just outside of Florence. A place with a swimming pool and a lush garden. A Tuscan landscape could be seen between the cypresses and pines that lined the garden wall; a valley, aged stone houses, vineyards and in the distance - bluish mountains. The house was rustic and simple, but tastefully furnished. On whitewashed walls hung delicate, skilfully executed watercolors, painted sometime by the beginning of the last century.

In our room was a bookshelf filled with books in German. They had apparently belonged to the same lady who had painted the aquarelles. It was mostly biographies and history books about the Austro-Hungarian Empire. There were also some diaries, which confirmed my assumption. They were written by a young lady, providing summaries of how she had spent her days; restaurant and museum visits, and fairly detailed descriptions of the views she had painted.

The woman who long ago had lived in our room had, according to her diary, made excursions around Florence and visited art treasures of small towns and villages. When I read her diaries I was seized by a desire to do as the young Austrian lady had done. Since our kindhearted friends had rented a minibus we went together to Arezzo, a city I was well acquainted with but never had visited before. In Arezzo, Roberto Benigni had staged his masterpiece Life Is Beautiful and in the same town unfolds the only scene I remember from Anthony Mingella´s film version of Ondaatje´s much better novel The English Patient. The Indian army engineer and deminer "Kip" Singh attaches a harness on and gives a flare to his mistress Hana (in the novel it was an old professor) and with block and tackle hoists her up under the arches of Arezzo´s St. Francis Basilica, so she can view Piero della Francesca's frescoes up-close.

For a long time I had wished to see those frescoes in situ. They were restored between 1991 and 2000 and now look as they did when they for the first time were revealed to an impressed crowd of amazed Arrezzo citizens, awed by the display of changing light, geometric rigor, discrete perspectives and heroic calmness. Giorgio Vasari, born in Arezzo twenty years after della Francesca's death, noted in his ground-breaking Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects that della Francesca's ingenuity had altered artists´ way of looking at thins, as well as their working methods:

Piero makes us realize how important it is to imitate real things and to draw them out, deriving them from reality itself. He accomplished this admirably well and caused modern painters to imitate him and to reach the heights of perfection we see in such things in our own times.

della Francesca's frescoes met my expectations; after I left the church I was seized by a desire to see them again. In pouring rain we continued towards Sansepolcro, Piero della Francesca´s birth place. On our way we made a stop in the village of Monterchi, to have a look at his Madonna del Parto, The Madonna of Birth. Tradition states that della Francesca created this tribute to a pregnant woman in a chapel by the village cemetery, where his mother rested in an unmarked grave. Vasari, without whom our knowledge of Renaissance artists would have been much more meager, wrote that Piero was called “della Francesca”, Francesca´s Piero, because his mother Francesca was pregnant with him when his father died and she had raised him single-handedly. It was she who discovered her son's unique talents and tirelessly brought him to fame and fortune.

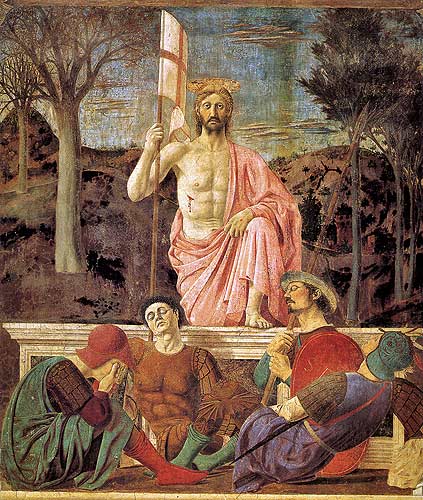

The pouring rain and the late hour prevented us from continuing to Sansepolcro. Accordingly, we did not see della Francesca´s The Risen Christ. Sansepolcro means “The Holy Sepulcher” and in its City Hall, Piero della Francesca had deepicted how an athletic Jesus in the middle of a Tuscan night quietly and dignified rises from his sarcophagus. Of course, I was slightly disappointed that we did not have time to see that masterpiece, but what grieved me the most, though I did not tell the others, was that we did not find the time to visit the undistinguished Church of San Lorenzo in Sansepulcro.

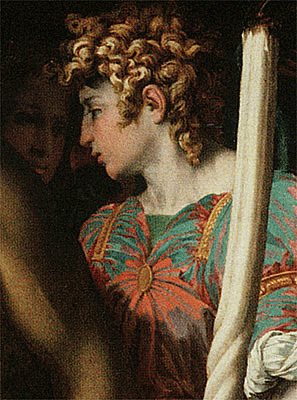

That dimly lit church displays a painting of a Jesus of an entirely different character than della Francesca´s triumphant athlete – not at all a conqueror of death, but rather one of its many victims. It is night in Jerusalem; God's darkness covers the Earth. However, a faint light falls on Jesus´ gray carcass. An emaciated chest rises over a sunken abdomen, as if the corpse has been displayed in a mortuary, or an anatomy theatre. As if illuminated by photography flashes Joseph of Amiratea´s red turban gleams in the dark , as do Nicodemus´ saffron orange robe, St. John´s brocade patterned shirt, Mary Magdalene ´s shiny curls and Mary´s, mother of Zebedee's sons, pale blue dress.

In the darkness behind the grief stricken mother of Jesus stands by the trunk of the cross a fearsome figure whose steely, gray eyes sparkle in the depths of a terrifying gloom as he is staring straight at us, while a crooked smile plays on his lips. However, If you close in to getter a better look at the ghostly face, you will find it is more as is the creature winds with his eyes and that the mouth is not smiling, it is rather malformed, or he is biting his lip. The night wind ruffles his hair´s matted curls. Who is it? Neither animal nor human; a grotesquely misshapen demon armed with shield and lance.

I have wondered if it could be possible to trace the origins of Fiorentino's unconventional representation of the dead Christ and what made him paint the strange monster in the background. It is a risky business - we do not know much more about Rosso Fiorentino than Vasari's stories and the limited amount of his preserved works.

Giovanni Battista di Jacopo Guasparre, who due to his red hair was known as Rosso Fiorentino, “The Red Florentine”, arrived in the provincial backwater of Sansepolcro in 1527, deeply shaken and worried by nasty experiences during Il Sacco di Roma, The Sack of Rome. It was the city's newly appointed bishop who had invited him to Sanspeolcro. Leonardo Tornabuoni was a childhood friend from Florence and he helped the controversial artist to obtainl local assignments. Tornabuoni appreciated his friend's peculiar art and in Rome, Rosso Fiorentino had on his behalf made an exceptionally beautiful and at the same time shocking painting.

This painting has some similarities with della Francesca´s presentation of the risen Christ in Sansepolcro´s town hall, but there are also major differences. While della Francesca´s Jesus rises proud and upright from his sarcophagus, in Fiorentino's painting he rests against it. della Francesca´s Jesus bares his muscular chest. Fiorentino´s Jesus is also well built, but unlike della Francesca´s heroic figure of salvation, he is stark naked and presented in full-length. By della Francesca, Jesus rises tall and triumphantly from his grave, while by Fiorentino his limp body is supported by unearthly beautiful angel boys. Fiorentino´s Jesus is dead, but his body shows no signs of rigor mortis; soft and relaxed it seems to presage that the World´s Savior soon will return from death, it is as if he is about to wake up from a deep slumber.

The angels seem to present Fiorentino´s Jesus to an unseen public, like when the priest during the Holy Communion lifts up the host and declares: Hoc est enim Corpus meum, quod pro vobis tradetur, this is my body, which is given for you. It is as if the naked Jesus is not resting against a sarcophagus, but against an altar. As if Christ´s body by a group of angelic ephebes is presented to an invisible congregation, just before it will be offered as an expiatory sacrifice. A performance similar to the one that the fanatical monk Girolamo Savoranola thirty years earlier had expressed in several sermons intended to shook the Florentines:

O foolish men, who by sinning are willing to lose of much peace and rest;agite poenitentiam, do penance; return to God and you will find complete rest; repent your errors; confess; make strong your intention never to sin again; receive the sacrament of Holy Communion which will make you, also, blessed! When we look at those who are converted and who follow the road of a good Christian life, who confess and receive Holy Communion often, we see in them something almost divine, humility, a spiritual rejoicing. Their faces have almost assumed angelic form. And, on the contrary, looking upon the faces of the wicked and stubbornly perverted and especially upon the faces of certain ecclesiastics when they are unbridled in their vices, we see them as demons, and worse than laymen.

The angels on Fiorentino's altarpiece have extraterrestrially beautiful faces, while the dead Jesus, like the artist himself, is red-haired as on all representations of Christ done by Fiorentino. He signed the painting with RUBEUS FLO FACIEBAT, "the Red Florentine made it".

Like many other artists of the time, Fiorentino was fascinated by the male body, regarding it as a conveyor of divine messages. So did, for example, also members of the in northern Italy so abundant flagellant brotherhoods, more commonly known as battuti or disciplinati. They envisaged that sinners´ bodies had to be disciplined and punished; their propensity to seduce the Christian soul had to be stopped. Flagellants tormented their own bodies as if they were disciplining a ferocious and disobedient dog, taming it into submission. Nonetheless,at the same time they perceived the body of Jesus as a mystical vessel for divine grace.

The first task the newly appointed bishop, Leonardo Tornabuoni, secured for his old friend was the execution of an altar-piece for Sansepolcro´s Church of the Holy Cross, which belonged to the Compagnia dei Battuti di Santa Croce, "Society of Those Battered for the Holy Cross ". A strange name which indicated that Fiorentino´s clients were flagellants. Since the mid-thirteenth century, flagellantism had spread through an Italy plagued by earthquakes, political instability, war and pestilence.

In Fiorentino's time, every Italian town contained several Catholic fraternities, which gathered around a saint, or specific rituals. Fraternities were associations of like-minded; for villagers who had flocked into the growing cities, for various groups of craftsmen and artists, as well as a variety of other groupings that had emerged when people felt a kind of kinship due to a common origin, business or ideas. Fraternities organized and paid for funerals and requiems for its members, while several of them also supported widows and orphans.

At first, flagellant movements arose sporadically in times of anxiety and distress. Despite regular condemnation by ecclesiastical authorities the phenomenon did not expire until after several centuries. After initial years of violent, public displays of self-torture, most members of flagellant communities generally limited themselves to privately wearing a hair-shirt, or a cilice, a narrow chain or metal belt with inward facing tags that is attached to the thigh, a torment still practiced by dedicated members of the popular Catholic organization Opus Dei. Only on certain, rare occasions did flagellants practice public self-inflections.

In Italy, where age-old traditions live on in some cities and villages, may strangely enough genuine flagellant rituals still be witnessed, foremost in the town of Guardia Sanframondi in Campania, which every seven year on the Day of the Holy Cross in September displays hundreds of men walking in long processions, while they scourge their backs bloody with whips, or tear their chests open with aspugna, a cork board with inserted needles. They sing laudes, hymns representing Jesus´ and his mother's suffering. Specially selected "helpers" regularly drown the torture instruments with wine, in order to disinfect them.

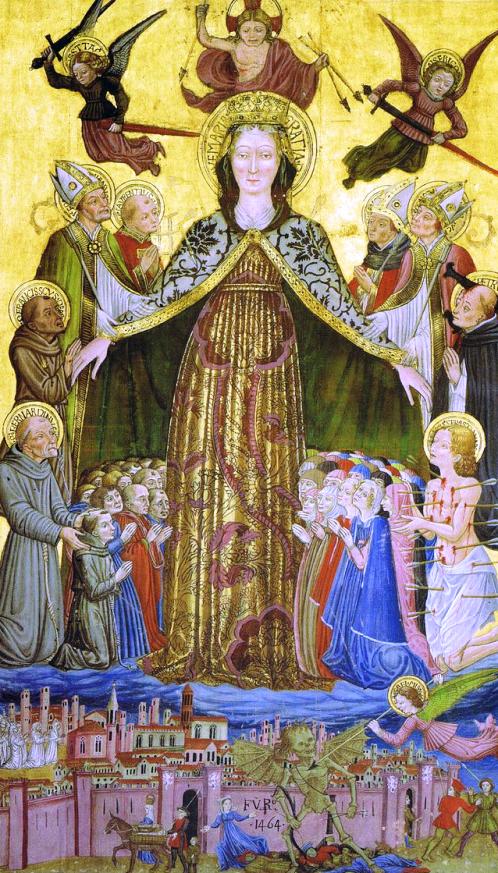

I Battenti, "the beaters", hide their faces under white hoods with holes cut out for the eyes. Like during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance the brotherhoods walk behind standards and paintings, so-called gonfalones. The more splendid thegonfalones are, the more evident they suggest how much money flagellants have been willing to sacrifice to God's greater glory

Gonfalones may still be seen in some Italian churches, for example in the San Francesco di Prato Church in Perugia. This beautiful gonfalone was painted in by a certain Nenedetto Bonfigli and depicts how the Madonna under her wide mantle protects Perugia's inhabitants from plague arrows raining down on them, fired at the behest of both God and the Devil, while Death in the form of a monstrous demon captures all those who happen to find themselves outside of Perugia´s protective walls.

Through their support to the art of painting, flagellants have contributed to its development. They have also been instrumental in the development of music. Their laudes spirituales have inspired the sung Catholic Mass, which later spawned a host of impressive choral works, such as Pergolesi's heartrending Stabat Mater, Verdi's eerie Dies Irae, from his late Quattro Pezzi Sacri, or why not such exotic fairs as the Congolese Missa Luba arranged by Guido Haazen, or Ariel Ramirez´ Argentine Missa Criolla.

So it was in accordance with their traditions that the Compagnia dei Battuti di Santa Croce contracted Rosso Fiorentino to make an impressive altar-piece for its church. The contract explicitly stated that Fiorentino had to "produce a Deposition that especially honors the body of Christ." It is not known if the brothers appreciated Fiorentino's work, but he was generously remunerated and gave a beautiful sketch of the dead Christ to the young, adoring Giorgio Vasari.

When the Brotherhood was dissolved the altarpiece was transferred to its current location in a church which at that time belonged to an orphanage. However, fifty years later a visiting bishop became so upset by the presentation of a stark naked Jesus that he ordered the immediate removal of such a blatantly "indecent" work of art. By the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 the painting was reinstated and enclosed by a sumptuously decorated niche.

Fiorentino was no stranger to flagellant notions. It is even probable that he was attracted by their ideas about the human body as a mirror of the soul. They believed that if you identified with the suffering Christ by exposing yourself to physical pain, you could maybe even redeem not only yourself from your sins, but also help others whose atonement you could take upon yourself as expiatory torment. They based their opinions on several Bible passages, among others Corinthians 6:15: "Do you not know that your bodies are members of Christ himself?" or Mark 8: 34-35:

Then he called the crowd to him along with his disciples and said: “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me and for the gospel will save it.

Similar beliefs are reflected in the Catholic Catechism, for example, in its article 2: 618:

The cross is the unique sacrifice of Christ, the "one mediator between God and men". But because in his incarnate divine person he has in some way united himself to every man, "the possibility of being made partners, in a way known to God, in the paschal mystery" is offered to all men. He calls his disciples to "take up [their] cross and follow [him]", for "Christ also suffered for [us], leaving [us] an example so that [we] should follow in his steps." In fact Jesus desires to associate with his redeeming sacrifice those who were to be its first beneficiaries. This is achieved supremely in the case of his mother, who was associated more intimately than any other person in the mystery of his redemptive suffering. “Apart from the cross there is no other ladder by which we may get to heaven.”

During Rosso Florentino´s Florentine adolescence there were no less ninety-six Catholic brotherhoods within the town and of them close to a third were flagellants. Several confraternities were suspected of not being completely housebroken, It was assumed that under the Church's cover several brethren in reality belonged to what could be characterized as political resistance cells, while other brotherhoods mainly served as an excuse for more or less uninhibited reveling. In particular were several flagellant confraternities under suspicion of being either politicized, or sites of illicit entertaining.

Parodies of fraternities and secret societies have been common as long as their existence, often making use of biblical allusions and sexual innuendos and they were customary in Medieval and Renaissance Florence as well. Writers like Benedetto Dei and Niccolò Machiavelli made fun of Catholic brotherhoods, distorting their names and mocking their members. It was especially during carnival that jokes referring to fraternities thrived. The young Rosso Fiorentino apparently participated in intellectual coteries where philosophy, art and politics were discussed, music played while jokes and obscene songs were shared and laughed at. Vasari, who knew him personally, heaps praise on his admired Rosso, stressing his conviviality :

His merits were such, that, if Fortune had secured less for him, she would have done him a very great wrong, for the reason that Rosso, in addition to his painting, was endowed with a most beautiful presence; his manner of speech was gracious and grave; he was an excellent musician, and had a fine knowledge of philosophy; and what was of greater import than all his other splendid qualities was this, that he always showed the invention of a poet in the grouping of his figures, besides being bold and well-grounded in draughtsmanship, graceful in manner, sublime in the highest flights of imagination, and a master of beautiful composition of scenes. In architecture he showed an extraordinary excellence; and he was always, however poor in circumstances, rich in the grandeur of his spirit. For this reason, whosoever shall follow in the labors of painting the walk pursued by Rosso, must be celebrated without ceasing, as are that master's works, which have no equals in boldness and are executed without effort and strain, since he kept them free of that dry and painful elaboration to which so many subject themselves in order to veil the worthlessness of their works with the cloak of importance.

Fiorentino counted among his friends the genial poet Francesco Berni who, through his comic and burlesque poetry, at a young age had become something of a legend. Berni´s poetry was admired for its accurate irony, lightness, sparkling wit, variation and fluent diction. His way of mixing serious farcical comedy became iconic and the genre came to be called "bernician poetry".

When Fiorentino was twenty years old he was commissioned to make two large frescoes in a Florentine convent, a Three Magi and an Assumption of the Virgin, in the latter Fiorentino included a portrait of his friend Francesco Berni. The popular poet is supposed to be one of the apostles, but is presented in a very strange manner, as if he were some kind of clown.

Like his friend Berni in his poetry, Rosso Fiorentino sometimes seems to amuse himself by parodying mass produced religious art. How else can one understand his representation of the Madonna and child as if they were a pair of wooden dolls admired by a grotesque and impertinent old saint, who looks like Gepetto, the old man who made Pinocchio, though that story was written 300 years later?

Vasari writes that dissatisfied customers often reacted negatively to what he calls Rosso's "astonishing excesses", i.e. his tendency to endow saints with expressions of a "grim desperation" so extreme that they were sometimes mistaken for demons. Vasari writes that Rosso's controversial fierezza, wildness/pride andstravaganza, eccentricity, were manifestations of his "conflicting idea", though Vasari does not explain what he means by that somewhat strange expression.

Despite his seemingly high-spirited nature ,Fiorentino´s author friend Francesco Berni was a melancholic and tormented man. While ridiculing glorified and beautiful poetry, such as Petrarch's writing, Berni could suddenly indulge in nightmarish excesses, an inspired madness that his friends described as sudden rashes of furore, a kind of creative fury connected with virtuosity, a feature often attributed to Michelangelo. Berni´s poetic caprices united emotional confusion and irreverent humor with dark passion. Berni declared that when he wrote, he was, spiritato, possessed by spirits. In one of his poems he depicts himself as an "infernal spirit," a "damned soul":

My very heart is a hell,

a hellish spirit in truth am I,

and a hellish fire is my fire

Bereft of all hope of reward,

and from the divine countenance,

is the wretched spirit of Hell

– and I am like him.

A great deal of Berni´s anxiety originated from a realization that a "different nature held him captive”. In Florence he was known as a poorly disguised homosexual, an orientation that by all accounts was not uncommon in circles that included his friend Rosso Fiorentino.

In his sermons the gloomy Savoranola exposed a thorough contempt of sodomites, the common term for homosexuals. This fanatical monk, whose hair-shirt we saw exhibited in his cell in San Marco´s Monastery in Florence the day after our visit to Arezzo, was offended by the flair and frivolity of Florentines who according to his opinion had become estranged from God's grace. He turned to his attentively listening audience:

With your authority, we might be able to pursue the sodomites, remove roadhouses, gambling dens, and taverns, and purge our whole city of vices and fill her with the splendour of virtue, showing thereby that this is the will of the Most High God, as He says to us and shows us daily through His prophets.

It was common knowledge that several Florentine citizens were openly gay. In German the word Florenzer came to have the same meaning as "homosexual". Sexual relations between men were nevertheless prohibited by law and a police force called the Ufficio della notte, The Night Agency, was endowed with the task of recording and punish homosexuality. Its registers from 1432 to 1502 are preserved and during that time 17,000 different men were examined for suspected "sodomy", this in a city with less than 40,000 inhabitants, of them 3 000 were fined, or imprisoned.

Among the acts of the Agency are several reports conerning sodomy within flagellant confraternities, perhaps not particularly surprising given the body fixation that thrived among them. For flagellants the body was not only an objekt of control and mortification, but also of worship, in the guise of Christ´s tortured body, revered in its incarnation of the eucharist, or as a means of meditation based on sacrificial and expiatory suffering. The naked or half-dressed Jesus was an occurring motif in art, often based on classical ideals inspired by ancient, scuptural fragments and/or speculations revolving around classical philosophy.

Rosso Fiorentino is classified as one of Mannierism´s foremost representatives. The term originates from the Italian maniera, from the Latin manuārius, “what the hand can do”. It might be translated as "style", or "manner". In art, maniera was used to describe the personal manner of reproducing reality of masters like Michelangelo and Raphael, who intreprted transformed it in such a way that both aesthetic pleasure and intellectual reflection were stimulated.

The Mannierists coveted virituosity, from virtú, virtue/power/skill. In their art they wanted to overcome predefined difficulties, while experimenting with light, color schemes, forms and elaborated body positions. Difficulties had to be defeated withbravura, i.e. elegant ease. In his treatise about how a perfect gentleman ought to act, Il Cortegiano, Baldassare Catiglione described this seemingly oblivious elegance as spezzatura, a kind of urbane negligence. Manniersim soon became equivalent with being “mannered”, i.e. “affected”, with a the connotation of “consciously exposing a strange behavior”, something some homosexuell men were accused of.

Rome in the 1520s may be compared to Paris at the beginning of the last century. Paris was then Europe's aesthetic, scientific, and to some extent also economic center. Young artists found their way there to learn from Old Masters, whose paintings were exhibited in the Louvre, but they also found inspiration from radicals like Gauguin, van Gogh, or Cezanne. Shortly before the First World War several new art movments materialized in Paris; like Cubism, Futurism, Orphism, Fauvism et. al. - then came the disaster and the old Europe went up in flames.

In 1512, Michelangelo shock up the Roman art world with his incredibly powerful and groundbreaking frecoes on the ceiling of the Sixtine Chapel and in 1520 the second great Renaissance master, Raphael, died, leaving behind a powerful group of talented, young adepts, who managed his tumultuous heritage. Impressive ancient sculptures had been dug up, like the Hellinistic group Laocoon and His Sons,which in 1506 was unearthed in a vineyard in central Rome and in 1480 a young Roman had fallen down into a cave and found himself surrounded by amazing wall paintings. He had ended up in the remains of Nero's Golden House and during the following decades room after room was by torch light explored by amazed artists, who became inspired by their "grotesque" frescoes, among them were Raphael and his group.

Young artists from all over Italy flocked to Rome and based on the teachings of older masters and the discoveries of ancient masterpieces they transformed contemporary art into something completely new - Mannerism. Then, just as in Paris in 1914, disaster struck. Paris survived relatively unscathed from the horrors of the First World War, though a whole generation of young men had been wounded, died or changed mentally. On the contrary, Rome was sacked and almost completely destroyed, the population fell from 55 000 to 10 000, while the innovative, young artists scattered across Europe, bringing with them their new ideas.

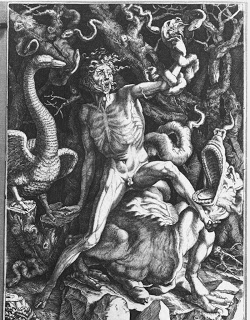

When the Florentine Giulio de Medici in 1523, under the name of Clement VII, became pope Rosso Fiorentino and his assistant Battistino, "a very beautiful boy," traveled to Rome where several lucrative assignments awaited them. In Rome were already Francesco Berni, Leonardo Tornabuoni and several other Florentine adventurers and artists. Besides frescos and oil paintings Fiorentino created, along with the engraver Gian Jacopo Caraglio, several remarkable graphic prints. Strangest was an etching named Furia, Fury. A distressing image representing a castrated and partially skinned man, entwined by serpents. Riding on a dragon he roars in a scrubby forest. Beside him stands a swan-like bird. No one has yet been able to figure out what this picture signifies, especially since it does not seem to allude to any known myth or allegory.

Possibly, the picture might be associated with Rosso Fiorentino's speculations about how art brings to life things that have been dead. When he worked in Perugia with an altarpiece depicting Jesus between the three Marys and Anna, the Virgin´s mother, he painted the upper part in accordance with his assignment, but filled the lower part with figures of his own invention, apparently personifications of astrological constellations.Rosso forbade people to enter the church, but was caught, together with his young assistant, in the act of “performing necromancy” in front of the unfinished painting. He was accused of witchcraft and not allowed to complete his work.

Rosso's fascination with death as a prerequisite for life, might have been a reason to why he so often depicted emaciated saints that almost looked like living cadavers. His friend, the poet Berni, was occasionally in his poems mocking attempts to achieve perfection that haunted so many other poets and artists of the time, not the least masters like Michelangelo and Raphael. Berni suggested that art can never reach perfection; any human creation is doomed to remain unfinished, though it contains opportunities for change and renewal.

The position of the enraged man's arms and legs, as well as the winding snakes are reminiscent of Laokoons position in the Hellenistic statue group that had been unearthed a few years before Fiorentino´s arrival in Rome. Possibly, the image can be linked to how hitherto forgotten dead antique ideals during Rosso´s time had been brought back to life. The snakes can then be linked to rebirth since by shedding their skin they constantly renew themselves. The dragon can accordingly be a salamander, which like gold and silver artefacts is born from fire. The bird can be linked to the myth of Leda, who Zeus seduced in the shape of a swan and who then gave birth to the beautiful Helen of Troy, archetype of beauty and destruction.

That the man is partially flayed may be an indication of how the new art was born from the dissection of dead bodies, something both Michelangelo and da Vinci had indulged in. That the etching is called Fury may imply the birth pains when something new is coming forth and the fierezza, wildness/pride that Rosso Fiorentino was known for.

That the man is castrated may allude to the impotence a creative artist might feel while being confronted with the criticism of an unsympathetic environment. Like most of Fiorentino´s depictions of Christ, the screaming man is completely naked. Alone and mercilessly exposed his conspicuous “physicality” covers a large portion of the image area. A few years later this etching came to be regarded as an eerie presage of the hideous disaster that hit Rome three years after its publication.

When the Imperial Army in 1527 had defeated a French army in northern Italy, its commander found himself unable to pay his mercenaries, 34,000 of them mutinied and forced him to lead them towards Rome. Most of them were goaded by the possibility of rewarding plunder, but some of them might also, at least partly, have been religiously motivated. Several of the 14 000 German Landsknechte were Protestants. During its march through Italy, the rebelling army was joined by a motley crew of common bandits and various insurgents. The Roman defense was weak, a 5 000 men strong group of vigilantes and 186 Papal Swiss Guards, who at the last moment managed to bring the Pope to safety in Castel Sant'Angelo.

Like a storm swell the undisciplined mercenaries inundated the city and indulged themselves in an orgy of ruthless violence. House after house was plundered, anyone who dared to offer resistance was killed immediately. Unarmed priests and monks were hardest hit, while nuns were dragged to brothels or sold in the streets to the murderous rabble. Churches were stripped of everything of value, tombs were broken up in a crazed the hunt for treasures. Saint Peter´s Basilica was used as stable, archives and libraries were torched after book pages had been torn out to be used as bedding for the horses.

Lutheran Landsknechte chose a pope of their own, dressed themselves up in ecclesial robes and tottered brawling back and forth through the city streets. After having paid 400 000 ducats for his life, the disgraced Clement VII was given safe passage out of the city. After eight months of violence and madness the soldiery began to leave the devastated city. Food was running out, while thousands of rotting corpses lied unburied and all manner of vermin poisoned wells and groundwater, the plague spread among soldiers and the ransacked civilian population.

Fiorentino had fared badly during the heady looting. The refined artist had been humiliated by a bunch of brutal German mercenaries who had moved into his residence. They used him as their house slave, stripped him of his elegant clothes and forced him to barefoot and single handed empty and load the entire stock of a cheese monger’s store. After a few weeks of suffering and humiliation Fiorentino succeeded to head north and finally showed up at his friend Tornabuoni´s residence in Sanspolcro, where he depicted Jesus as a corpse while darkness covers the earth. In the dark background, by the blood stained cross, we meet the bewildered gaze of a demon. Who is he?

Two explanations are usually provided – the demon represents an evil and triumphant presence relishing in the death of Christ. It is the Devil who enjoys the result of his evil deeds. However, the shield and spear of the strange creature indicate that he represents Longinus, the Roman soldier who stuck his spear into Jesus' side. According to Catholic mythology Longinus is a saint, not at all a demon. The shield bearing creature may thus be one of Rosso´s subtle jokes, yet another example of his mockery of a religious art worn down by insipid conventions, perhaps the “demon” is nothing less than a portrait of his monkey.

Vasari tells an amusing anecdote about Rosso's large and domesticated Barbary macaque, the same kind of macaque that still lives on the rock of Gibraltar. According to Vasari this monkey was more like a man than aan animal and Rosso loved it "as his own self." When they lived together in Florence, Rosso´s assistant Battistino taught the macaque how to steal grapes from a nearby monastery garden. However, a monk caught the animal in the act and tried to flog it with a stick. The monkey escaped, but the friars forced Rosso to chain a weight to his beloved pet, so that it would not be able to sneak into the garden anymore. Nevertheless, the monkey taught itself to carry the weight in its hands and jump off to the monastery, where it crushed the roof tiles of the monks´ dormitory by pounding them with the weight. Rosso and Battistino laughed when they during a subsequent downpour heard how the friars cursed them and their monkey while rain water was pouring down on their beds.

However, if you compare a macaque´s face with the creature in the altarpiece they do not look alike. Perhaps the demon is after all a human being. He might depict a "wild man," a representative of the untamed, still unsaved humanity who with wonder and bewilderment witness the Christian mystery that unfolds in front of his uncomprehending stare.

"Wild men" were during the High Middle Ages a fascinating subject among European courtiers. They appeared in legends and fables – in Arthurian romances and oral traditions, where, among other creatures they took the form of trolls and orcs. One of the most popular pastimes among the nobility were "wild men dances", when ladies and gentlemen allowed themselves to be unleashed from the strict rules courtly dancing. Savages often occur in the arts. Lacking an intelligible language and common sense these furred creatures like giant children sneak around in the depth of dark forests. They have a violent temper and possess magical powers. They might tear lonely wanderer in pieces. Several of them are cannibals, they rape women and abduct children, preferably unbaptized ones, since wild men are pagans and hate anything that might pose a threat to their uninhibited nature. They tear up trees by their roots, cause hail storms and distort the vision of people they encounter. Wild men inhabit isolated caves or live under ground. They rule over forest animals, personifies nature's untamed forces and are thus both inferior and superior to man.

Fiorentino's savage contemplates the dead Christ in a manner that appears to be both menacing and confused. Has the unbridled nature finally defeated God's plan of salvation? Has the Lord's attempt to use love and compassion to improve the degraded state of his creation finally been thwarted by his son's death?

Two years before Fiorentino's birth, a whole new world had unexpectedly been discovered by the Europeans. Across the Atlantic lived peoples who sacrificed and even ate each other. There were incomprehensibly vast realms of gold, silver, previously unknown fruits and crops, vast virgin forests inhabited by wild men and women. A parallel world - maybe evil, maybe good, - but populated by persons who lacked any knowledge what so ever of either God or His son. Is it perhaps such a savage who in front of the cross are pondering on the strange spectacle that unfolds before him?

Maybe it was the New World was the Devil´s abode? As in a Portuguese depiction of Hell where the Devil from a throne supervises the torture of damned souls. According to a Renaissance prototype of American savages the Devil wears a mask and has a plumaged head dress, like those worn by members of some Amazonic tribes.

Perhaps the answer to the demon's identity is to be found in Vasari's mentioning about the macaque monkey as being like Rosso´s "own self." It may thus not be a demon who watches the dead Christ; it might be Rosso Fiorentino himself. The artist as an outsider, a mere observer. Rosso the elegant esthete, who mocked Christian art conventions. Rosso, the innovator, the skilled artist who excelled in all arts. Rosso, the homosexual eccentric who in Rome had lived through a humiliating hell and at first hand experienced man´s bottomless evil, how "darkness covered the Earth", while Christian symbols were defiled and the commandment of love was neglected by executioners and victims alike. Rosso, the admirer of the human body, who from his position in darkness and seclusion contemplates the sorry sight of a dead Jesus. Rosso, who depicted a screaming, angry and vulnerable individual, skinned and castrated by an unsympathetic environment. Is Rosso the monkey? The freak, who behind a contorted mask watches and tries to understand a Christian mystery that according to the Catholic Catechism constitutes the ladder "on which one can ascend into heaven"?

Rosso's life ended tragically. He entered into the service of Francis I of France, who appreciated him both as an artist and social companion, paying him generously for his innovative work on the castle of Fontainebleu. According to Vasari, Rosso was "on intimate terms" with a Florentine, Francesco di Pellegrino, "who appreciated the art of painting". However, their relaionship went sour. Rosso brought Pellegrino to court, accusing him of theft, though when it turned out that his former friend was innocent Rosso Fiorentino killed himself out of shame and despair.

Anderson, Lisa (2011) “Rosso’s Fury: Engraving, Antique Sculpture, and the Topos of Death.” Master of Arts Thesis, University of British Colombia. Bernheimer, Richard (1952). Wild men in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Campbell, Stephen J. (2002) “Fare una Cosa Morta Parer Viva: Michelangelo, Rosso and the (Un)divinity of Art”, in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 84, No. 4. Castiglione, Baldassare (1967) The Book of the Courtier. Harmondsworth/Middlesex: Penguin Books. Ciardi, Paolo Roberto and Alberto Mugnani (1991) Rosso Fiorentino: Catalogo completeo dei depinti. Florens: Cantini. Chastel, André (1983) The Sack of Rome 1527. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Laciani, Carlo and Antonio Natali (2014) “Rosso Fiorentino” Art e Dossier, No. 308. Henderson, John (1994) Piety and Charity in Late Medieval Florence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Rocke, Michel (1997) Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Shearman, John (1981) Mannerism. Harmondsworth/Middlesex: Penguin Books. Taussig, Michael (1987) Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Vasari, Giorgio (1991) Lives of the Artists. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)