SHUNAMATISM: Paris, authors, horny old men and abused virgins

Especially Americans seem to have a romantic view of Paris as the capital of love, art and good food, at least if you believe the image of the French capital created and supported by Hollywood ̶ La Ville Lumière, Le Gai Paris. My first experiences of that town were not particularly positive, probably due to my flawed French and fact that the French cuisine did not impress me as much as the Italian.

A particularly unpleasant memory of mine stems from the time I used to travel through Europe with Interrail. As I mentioned in a previous blog, during a stay at the Riviera, my money ran out, but I agreed to meet with some friends in Paris and thus solve my economic concerns However, at the hostel in Choisy-Le-Roi, a suburb to Paris that I became relatively familiar with several years later since there is an IKEA store there, they assured me that my comrades were not there.

My few coins were insufficient for a deposit. It was before the credit cards and I asked if I could leave my passport as security and thereby get a place to sleep until my friends showed up. The guy at the reception desk hesitated and asked to have a look at the passport. While he leafed through it an unofficial press card fell out. In English and Swedish it informed that I occasionally published articles for Norra Skåne, the local newspaper. A few years later I used it successfully during a visit to the Edinburgh International Festival.

̶ What is this? he wondered.

̶ Une carte de presse suédoise, I replied, more or less truthfully, so much I managed to say in my French.

̶ Cela ne suffit pas. Vous êtes à aller en ville, he declared and I understood that I could not stay. When I in English wondered if I could possibly sleep under a bush in the hostel's fenced-in park, he lost patience:

̶ Absolument pas! C'est complètement impossible. Vous devez immédiatement partir d'ici.

The message was perfectly clear and I left the place. Night had fallen, there was rain in the air. I wandered around in the inhospitable Choisy-Le-Roi, not finding any suitable place to sleep. The parks were occupied by a dubious night clientele and after some reluctance I slipped back into the hostel's park by climbing over its high fence and installed myself under a leafy bush. While lying there, slicing a salami with my pocket knife, I discovered that I was not alone. Muffled voices in foreign languages could be heard in the dark, soon changing into snoring.

In spite of drizzle and worries about discovery, I managed to fall asleep, though the barking of dogs soon brutally pulled me out of confused dreams. Dazed I saw flashlights bobbing across the lawn. I hitched my backpack and rushed off with a steady grip on the knife and sausage. I left the sleeping mat behind. Heard a dog yelping behind my back, while someone screamed to me to stop once. I did not turn around, instead I threw myself against the metal mesh of the fence trying to climb over it as fast as I possibly could. I had not come even halfway over when someone got hold of the lining of my trousers and pulled me down. Reaching the ground I stumbled backwards, while staring straight into the yapping jaws of a furious dog.

Thank goodness someone was holding it back, though in the dark I caught the glimpse of a raised baton. In my poor French I desperately stammered a few words:

̶ Ne me frappe pas! Je suis suédois!

My attacker calmed down at once, laughing out loud. He turned around shouting to his comrades:

̶ Ne frappez pas celui-ci! Il dit qu'il est suédois! Don´t beat that hit this one, he says he's Swedish!

With a steady grip round my upper arm my captor brought me to the hostel's entrance. A wide staircase led to large glass doors through which a white neon light illuminated the scene in front of me, as if it had been a theatre stage. What took place there was something that I up until now, after more than forty years, still has a clear memory of. Surrounded by sombre men and their threatening dogs, one of the guardians was in full swing beating a man rolling around on the ground. Blows and kicks sounded against the body with unpleasant, strangely blunt, muffled thuds. The beaten and utterly defenceless man squealed incessantly:

̶ Je suis désolé! je suis désolé! Je t'en prie! Laisse faire! Arrêt! Arrêt! I´m Sorry! I´m Sorry! I beg you! Let me be! Stop it! Stop it!

Everyone kept silent. All that could be heard was the sound of the disgusting, systematic beating and the thrashed man's constant pleading. Time seemed to be drawn out. A crouching group of homeless men huddled in a corner, watched over by an attentive Doberman on a short leash.

My captor had let go of my right arm and was with fascinated attention watching the nasty scene in front of us. The perpetrator seemed to be obsessed, methodically whacking his wretched victim. The neon light made the sweat of his brow glitter. The face was distorted into a furious mask. As if hypnotized I staggered towards the enraged attacker and tapped him lightly on the shoulder. I still had a steady grip on my sausage and pen knife.

̶ Calmez vous s'il vous plait. Please, calm down.

The raving man furiously turned around fixing a mad stare at me. His sclerae shone white. A tight fist struck me straight on one cheek, making me reel towards the entrance staircase, where I fell headlong. While I was laying there I heard police sirens and saw how my antagonist straightened up. Together we glanced towards the gates where the rotating blue lights of police cars could be seen. The cars braked in, in the spinning shadow play of blue lightning the police violently threw the meek group of vagrants into a van. Les flics did not seem to be bothered at all by the fact that one of wretched men had to be picked up from the ground, with all signs of having been brutally beaten.

As suddenly as they had appeared, the police cars disappeared. I rose up. My chin was hot. It hurt as I stroked it, but it did not bleed. Nobody seemed to take any notice of me. The guards disappeared into the dark, followed by their dogs. I stood shouldering my backpack and with my sausage and knife still in my hand. Once again I stroke my throbbing cheek, turned around and next to me I discovered the guy from the front desk. The one who had told me that I was not welcome to sleep at the hostel. In friendly but broken English the receptionist asked me:

̶ Tough going. Non?

I answered:

̶ It was awful. How could you let him beat the poor guy like that?

He gave me an embarrassed smile:

̶ Il le méritait. C'est lui qui a commencé. Comment dites-vous? He had it coming? He deserved it. It was he who started it all. How do you say? He had it coming?

I repeated:

̶ C'était horrible. And the police didn´t do anything.

He shrugged his shoulders:

̶ Oh, ils savent comment traiter ces gens. Ne faites jamais confiance à un beur ou à un wog.

I did not really understand what he was saying, but caught its racism. Apparently he tried to tell me that the police knew how to treat Arabs and Africans. I became ashamed of my own subconscious racism that had made me try to save my own skin by stating I was Swedish. The guy from the front desk evidently remembered that I had something to do with the Press and thus assumed that I even could have disturbing influence on the reputation of the hostel. He wondered:

̶ Your … comment dis joue? … side of face, hurts?

I grasped at the straw. I could use this:

̶ Oui, beaucoup. Yes, it really hurts.

He grabbed my shoulders:

̶ Ne t'inquiète pas. Je vais réparer ça. Don´t you worry. I'll fix this.

He brought me down to the boiler room, got a mattress, made it up with sheets and a pillow. In his French-English he explained that I could sleep down there until my pals showed up. I spent two nights in the boiler room, but my friends never showed up. The receptionist and I parted as friends. He would absolutely not receive any payment, something I was grateful for since I did not have a single centime left. What I had was unfortunately some confirmed prejudices ̶ Paris was definitely a tough and hostile city, where racism was flourishing, both among ordinary guys and the police. Well, it is probably like that in most places here on earth, but for me Paris appeared in a particularily bad light

However, my averseness towards the city vanished when I between 2009 and 2012 came to live and work in Paris. I lived in the Quartier Latin, in a comfortable apartment with balcony, kitchen and bathroom, spending my evenings and weekends on walks and museum visits. Quite often I went to the opera and on several evenings I ended up in the small cinemas of the neighbourhood. I often received fiends from Sweden and visited my family in Rome and England, while my colleagues took good care of me. It rained quite often and the winters were raw. I never became a close friend of the French cuisine, and the banlieues were gloomy, though it would be a lie to deny that I did enjoy the city.

Like many other major cities, for example London and Rome, several houses in Paris have memorial plaques informing you that authors or composers have lived in them and there written their famous works. An unusually gloomy day, as often in Paris with drizzle and penetrating dampness, I had visited Musée de Cluny, the medieval museum housed in an ancient former Roman bathing facility. I came there quite often to admire the six exquisite gothic tapestries, La Dame à la Licorne, which tell the story of the unicorn. Afterwards I had dinner in a nearby Italian restaurant and botanized in the bookstores. On my way home I passed the Sorbonne University and at a nearby street I passed Hôtel Trois Collèges, on the wall was one those plaques, which read:

Here did the author Gabriel García Márquez, Nobel Prize in Literature 1982, in 1956 write his novel No One Writes to the Colonel.

The bronze plaque was adorned with a bust of García Márquez. Of course, I took a photograph of this by me highly appreciated author. Somewhat higher up on Rue Cuias I almost tripped over a clochard who was lying flat on the wet pavement. Since it was cold and humid, I became worried and leaned over him to see if he was alive. He lifted his head and shouted furiously:

̶ Laissez moi être! Sortez! Let me be! Fuck off!

He did not seem to be drunk, just angry and irritated. After giving me an angered and crazy look he lowered his head on the stuffed plastic bag he used as a pillow. I continued a couple of steps, turned around and could not avoid taking a photograph of the strange scene with the homeless guy and in the background the hotel where both García Marquéz and Vargas Llosa had lived and written some of their books. Unfortunately, the photograph has ended up in one of my drawers somewhere in Bjärnum, but I will attach it here as soon as I find it.

After I had returned home I found out that García Marquéz had been staying at the hotel when it was called Hôtel de Flandre and he had not only No One Writes to the Colonel there, but also The Evil Hour. In 1957 the twenty-year-old Mario Vargas Llosa had stayed in the hotel for a month while making a break from his studies in Barcelona, by that time García Marquéz had just moved out. Madame Lacroix who had been responsible for the hotel while García Marquéz was living there and whom he recalled with some affection, later became responsible for the nearby Hôtel Wetter, where Vargas Llosa became acquainted with her after he in 1960 had moved in there with his thirteen-year-older wife Julia Urquidi. In his sumptuous and quite hilarious novel Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter Vargas Llosa is inspired by the romance he had with Julia in Lima of the fifties. At that time she was sister-in-law to one of his uncles.

Julia Urquidi and Vargas Llosa were short of money and soon had to move out of Hôtel Wetter. However, Vargas Llosa lived in the same quarter until 1966, a year before that he had divorced Julia and married his cousin Partricia Llosa, who was a student at the nearby Sorbonne University.

It was only after he had left Paris that Vargas Llosa became personally acquainted with García Marquéz. They met for the first time in Caracas. Four years later, in 1971, Vargas Llosa presented his doctoral thesis on García Marquéz's writings at the Universidad Complutense in Madrid: Gabriel García Marquéz: Historia de un Deicidio. In his thesis Vargas Llosa developed an idea that a great writer changes reality by imposing his own vision of human existence. An insight Vargas Llosa gained after listening to García Marquéz telling him about a return to the village of his childhood and youth, Aracataca. After being away for many years he found it to be nasty, dusty and diminished, not at all as it had appeared in his memories. At that moment García Marquéz decided to transform Aracataca according to his memories of the place, his fantasies about how it once had been and maybe even a vision of how it should have been. How he in his own mind perceived something he had thought he had been familiar with. That was how the village of Macondo was born and developed in García Marquéz's unforgettable novel Hundred Years of Solitude ̶ a parallel reality, a landscape seen through a temperament, perhaps more truthful, or at least more interesting, than what we assume to be “the reality”. García Marquéz thus became a creator, a competitor to God. Vargas Llosa wrote:

Writing novels is a rebellion, an attack on reality, on God and his creation, which most of us perceive as reality. A novel is an attempt to correct, change, and arrange reality, an artificial creation accomplished by a novelist.

A strong friendship developed between the two authors, but it was definitely crushed five years later, outside a cinema in Mexico City. After the performance, García Marquéz approached Vargas Llosa with open arms shouting: "Mario!" But was met with a fist straight into one eye. The Peruvian turned his back on the baffled García Marquèz, while muttering: “How dare you come and greet me after what you did to Patricia in Barcelona!”

The reason for the unexpected blow was that Vargas Llosa had left his wife and moved to Stockholm with a Swedish air hostess. After a short while he did however crawl to the cross and returned to Patricia Llosa and their three children in Barcelona, though she had previously sought comfort and advice from García Marquéz and his wife Mercedes, who had advised Patricia to get a divorce from Mario Vargas Llosa, something she obtained first forty years later.

However, there were several other reasons for the broken friendship between the two master narrators. Not least political ones. When the Cuban regime in 1971, claiming that he had committed crimes the regime itself had invented, jailed the author Heberto Padilla, several former Cuban-friendly writers knew that Padilla had fallen into disgrace due to the satirical stance of his poems and a so far unpublished novel, Heroes are Grazing in My Garden. Vargas Llosa swore himself free from his support of Castro, while García Marquéz continued to provide an indiscriminating backing to the Cuban caudillo.

At that time García Marquéz did not personally know Castro, but his stout support of the Cuban Revolution made him travel to Havana and interview Padilla at the airport, where the poet ̶ after having been forced to publish a 4 000 word long humiliating "confession", in the best Stalinist manner ̶ was waiting to be expelled. Even if Padilla had told García Marquéz about his suffering in Castro´s prisons, the Colombian author insisted that a publication of his book would damage Socialism and furthermore persisted in his absurd belief that Padilla was a CIA agent.

Castro and García Marquéz first met in 1977, but since then they were in constant contact. García Marquéz owned until his death in 2014 a large villa outside of Havana, which Fidel had given him. On the wreath that Fidel sent to García Marquéz´s funeral in Mexico City, he had written "to my endearing friend". Vargas Llosa used, half seriously, half-jokingly, call García Marquéz "Castro's courtesan."

García Marquez described his friendship with Fidel as being primarily based on the dictator´s great interest in literature. According to the Colombian writer Fidel was a diligent and critical reader, who in great detail commented on each of García Marquéz´s novels. Apparently, Castro shared his friend Che Guevara's view of the so-called Latin American literary boom:

This entire Latin American boom is a result of the Cuban Revolution. Without our Revolution, all these fellows would be nothing more than a bunch of vagabonds rambling around in Paris.

Vargas Llosa´s later view of socialism and communism emerged with all clarity in what he wrote in the book Manual del perfecto idiota latinoamericano, Manual for the perfect Latin American idiot. I found it to be a rather funny satire of sveral of those, in my opinion, quite unworldly and exaggeratedly revolutionary Latin Americans I had come to know throughout the years. One of them, the Argentine sociology professor Atilio Borón (a stout Fidel admirer), whom I learned to know during my time at Sida (the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) and occasionally hanged out with, described the Manual as:

... a monster created by Mario Vargas Llosa, which unambiguously demonstrates that the Right is unable to come up with any sustainable ideas and that their discourse constantly fails to interpret any social process, which by them is described from a most elementary and banal intellectual level.

Nevertheless, the violent reaction of Vargas Llosa outside the Mexican cinema may after all primarily be associated with the macho culture that he and García Marquéz, from their early years on, have been constantly influenced by. Even if they undoubtedly were sophisticated cosmopolites, their stories steam off Latin American machismo. This pestilence may be described through a generalizing excerpt from a book about Mexican customs:

Machismo meant the repudiation of all “feminine” virtues such as unselfishness, kindness, frankness and truthfulness. It meant being willing to lie without compunction, to be suspicious, envious jealous malicious, vindictive, brutal and finally, to be willing to fight and kill without hesitation to protect one´s manly image. Machismo meant that a man could not let anything detract from his image of himself as a man´s man, regardless of the suffering it brought to himself and the women around him […] The proof of every man´s manliness was his ability to completely dominate his wife and children, to have sexual relations with any woman he wanted, to never let anyone question, deprecate or attempt to thwart his manhood, and never to reveal his true feelings to anyone lest they somehow take advantage of him.

Magic and cynicism, love and power, corruption and salvation are prevalent ingredients in the impressive frescoes of the great Latin American representatives of what has come to be called magical realism: Alejo Carpentier, Ernesto Sabato, Julio Cortázar, Jorge Amado, Carlo Scorza, Miguel Angelo Asturias, Augusto Roa Bastos, Roberto Bolaño, to name just a few of these captivating masters, who with exquisite language and unforgettable imagery have enriched my life. Among these we find of course and not the least ̶ Gabriel García Marquéz.

Gabriel García Marquéz depicts obsession in such a manner that it may be interpreted in several different ways. For example, I was surprised when some of my friends perceived his novel Love in the Time of Cholera as a magnificent description of a man's unshakable love for a the first woman he came to desire. They perceived the main character as a romantic dreamer, though I considered him as a cold cynic taking advantage of countless women, whom he wrecked in a search of a love he finally found ̶ hence the name of the novel Love in the Time of Cholera. My interpretation indicated that the main character´s entire personality was sickly, even unpleasant and dangerous.

García Marquéz male protagonists often suffer from unhealthy follies, in the midst of all these lush and exotic tropics, there is an odour of corruption, even necrophilia. It is almost unobtrusively detectable in Hundreds Years of Solitude, The Autumn of the Patriarch, The General in his Labyrinth, Of Love and Other Demons, but in this we also find some of the greatness of these amazing novels.

A similar scent is also apparent in some Vargas Llosa's of masterpieces, such as The Green House and The War of the End of the World, but there are also some other unpleasant details, hidden under a flowing narrative and multifarious imagery. However, I assume I have found more unpleasant details with Vargas Llosa than by García Marquéz and their presence seems to be gaining strength in some of Vargas Llosa´s later novels.

For several days and evenings, I was captivated by The War of the End of the World, although I could clearly see how intimately it was based on the fascinating documentary book by the Brazilian journalist Euclides da Cunha Os Sertões, Rebellion in the Backlands, from 1902. Vargas Llosa's novel stood nevertheless free, powerful and independent beside da Cunha's impressive work. However, I found Vargas Llosa's celebrated The Feast of the Goat to be worse when it came to its models and sources. Well written it dealt with the Dominican dictator Trujillo, an absurd dictatorship and personality, which madness constituted a perfectly factual example of magical realism, greater than life, more bizarre than any imaginary fiction. I had read quite a lot about Trujillo long before I came across the The Feast of the Goat, when I did I became amazed by how much Vargas Llosa´s text depended on Dominican and other sources, without him giving them any credit. Of course, the findings presented by these texts were in the public domain, but occasionally Vargas Llosa followed them almost verbatim, not the least Bernard Diederich's well-documented and excellently told book Trujillo: Death of the Goat and it was with good reason that the New Zeelandian journalist accused Vargas Llosa of plagiarism.

I soon realized that Vargas Llosa nurtured an unhealthy attraction to the brothel-life that is so forthrightly depicted not only in Fernando Botero's paintings, but also in several Latin American novels, like Juan Carlos Onetti´s Body Snatcher, or Pedro Juan Gutiérrez´s Dirty Havana Trilogy, novels that are far from being lousy pornography (though I have some doubts about Gutiérrez, who I found to be undeservedly celebrated) but nevertheless they move about in an erotically loaded atmosphere. Vargas Llosa's taste for soft porn becomes apparent in novels like In Praise of the Stepmother and The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto. It also pops up in The Bad Girl, which nevertheless was not as bad as the other two novels. It is easy to find the roots of this fascination for superficial sex in Vargas Llosa's interesting political autobiography A Fish in the Water: A Memoir, which while describing his political career as a presidential candidate in Peru, also deals with his youth´s journalism and frequent visits to Lima's brothels. However, I became very disappointed when I recently read his novel The Neighborhood, where Vargas Llosa unnecessarily trashes what could have been an exciting political thriller with an gratuitous and tacky Lesbian love story, completely in line with Emmanuelle Arsan's salon-pornographic products. How could a Nobel Prize laureate come up with such crap?

Unfortunately, I also think that García Marquéz's suffered a similar death by drowning in his last novel, Memories of my Melancholy Whores. Already the introduction is ominous:

THE YEAR I turned ninety, I wanted to give myself the gift of a night of wild love with an adolescent virgin. I thought of Rosa Cabarcas, the owner of an illicit house who would inform her good clients when she had a new girl available. […] insisting the girl had to be a virgin and available that very night. She asked in alarm: What are you trying to prove? Nothing, I replied, wounded to the core, I know very well what I can and cannot do. […] I have never gone to bed with a woman I didn't pay, and the few who weren't in the profession I persuaded, by argument or by force, to take money even if they threw it in the trash. When I was twenty I began to keep a record listing name, age, place, and a brief notation on the circumstances and style of lovemaking. By the time I was fifty there were 514 women with whom I had been at least once. I stopped making the list when my body no longer allowed me to have so many and I could keep track of them without paper.

García Marquéz still kept his excellent treatment of language intact. He wrote about "the transforming power of love". About a love that “never matures, but always remains childish in its expressions". The main character becomes aware of how his unrestrained quest for sexual satisfaction has hurt both him and others. He was unable to seek and find love's innermost core of community and hence its invigorating power. Nevertheless, nothing of that could dispel the novel's character of unhealthy senility.

Sure ... the aging writer is describing himself as forlorn and ugly. He realizes that his life has been lost to an egocentric pursuit of sexual bliss. He is ignorant of the meaning of true love. Furthermore, it is quite conceivable to interpret the old narrator's fantasies while he rests beside the body of a naked adolescent girl as a metaphor for fiction´s unfulfilled striving to replace reality with something ideal. However, the effect of all this remains as a complete denial of the sleeping girl's own life, her integrity and dignity. A cynical rape of her personality. The aged narrator considers her to be his exclusive property. When he suspects that the brothel madam has sold the girl to another customer, the aged journalist turns into a raving, destructive beast, something that may be interpreted as a powerful depiction of machismo´s harmful impact of on its male victims and their surroundings. However, this effect is soon lost when the novel ends with the narrator's realization that his "chaste" love nights are bestowing power and new life to his writings. It becomes even worse when his jealousy is defeated by a sheltering patriarchal attitude as the old sex maniac, together with the cynical madam, start to watch over the girl's wellbeing, like a couple of loving parents. Accordingly, the novel assumes a fairy tale´s happy ending. Is it irony or wishful thinking? I don´t know.

The fourteen-year-old girl, whom the old debaucher calls Delgadina, The Little Skinny One, is in the novel not provided with a voice of her own. She sleeps and thus remains silent during her "love nights" with the aged paramour, who does not want to learn anything about her daily existence, claiming that it would spoil his dream image of her. Is this not extremely arrogant, self-serving and even perverse? No one can make me appreciate this Marquéz´s last concoction. For me the novel became an unpleasant fly in the ointment, disturbing my high appreciation of the author Gabriel García Marquéz, all the joy and pleasure his tales have given me. Memorias de mis putas tristes became Una memoria triste de mi García Marquéz.

One origin of Memories of my Melancholy Whores may be traced to a short story in García Marquéz's Strange Pilgrims, published in 1992, though the story The Airplane of the Sleeping Beauty was written already in 1982. Like Memories of my Melancholy Whores it deals with sublimated sexuality and contemplation/peeping:

She was beautiful, elastic, with tender skin the color of bread and green almond-shaped eyes. Her hair was straight and black and reached her waist, and she had an aura of rich ancestry, the kind that could have been from Indonesia or the Andes. She dressed in fine taste: a linen jacket, a natural silk blouse with pale flowers, rough linen pants, and high heeled shoes the color of bougainvillea flowers. “This is the most beautiful woman that I have ever seen in my life,” I thought, when I saw her pass with her stealthy, long, lioness strides while I got in line to board the plane to New York at the Charles de Gaulle airport in Paris. She was a supernatural apparition that lasted only an instant, then disappeared into the crowd in the lobby.

To the narrator's great pleasure this supernatural beauty is on the aircraft seated next to him. However, after having swallowed two sleeping pills, she slept deeply throughout the entire trip, while the narrator is surveying her, fantasising and dreaming about erotic encounters:

Later I reclined my seat to the level of hers, and we lay closer than we would have in a full-size bed. The aura of her breath was the same as her sorrowful voice, and her skin released a faint aroma that could only be the very scent of her beauty. It was incredible to me: the previous spring I had read a lovely novella by Yasunarl Kawabata about the ancient bourgeois of Kyoto who would pay enormous sums to spend the night studying the most beautiful women of the city, naked and drugged, while they, the men, were dying of love in the same bed.

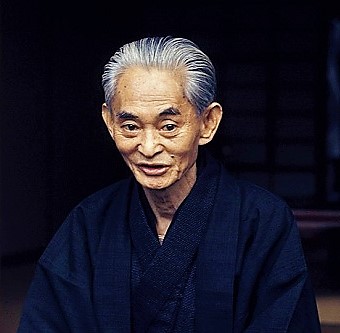

I wonder if García Marquéz had read the same book that I had once come across. Before reading any of García Marquéz stories I had read several of Kawabata's short and strangely exquisite novels. When I was fourteen years old I became captivated by The Old Capital. Never before had I read something like that; a quiet, beautiful depiction of an existence where beauty was at the centre. Nature, flowers and art worked in harmony to create an outstanding, sensitive imagery of an exotic environment with kimonos, Japanese gardens and Buddhist temples.

.jpg)

At the age of four, Yasunari Kawabata had lost both his parents, growing up with his grandparents, though his grandmother died when he was seven years old and his grandfather when he was seventeen. Perhaps it is these experiences that in Kawabata's work create a sense of distance. He appears as an observer, endowed with an exaggerated, aesthetic sensitivity. In every story he describes in detail all five senses ̶ taste, sight, touch, smell and sound ̶ though all of his narrators remain outsiders: " I feel as though I have never held a woman’s hand in a romantic sense […] Am I a happy man deserving of pity? " Kawabata was awarded the 1968 Nobel Prize in Literature, taking his own life four years later.

House of the Sleeping Beauties is not about "the ancient bourgeois of Kyoto who would pay enormous sums to spend the night studying the most beautiful women of the city, naked and drugged, while they, the men, were dying of love in the same bed.” The “house” is an isolated brothel, placed somewhere in the countryside and is characterized by ancient traditions ̶ the discreet, apparently strict, but secretive madam is dressed in kimonos and serves tea, furnishings are sparse and there are rules for how the visiting old men have to behave in the proximity of the sleeping, naked girls; these are all young virgins, passive and drugged. The proximity of nature is noticeable; sighing of tree crowns and the roar of an open sea can be heard through the thin walls. When it rains coolness and the scent of flowers sip in. We are not told where the brothel can be found, only that it is frequented by old men and of those we only learn to know "old Eguchi", who is sixty seven years old, actually only three years older than I am now.

Naked old Eguchi spend four nights beside different young women. Strangely enough there are two girls present during his last night at the brothel. He touches the gilrs, look at them and inhales their fresh scent of youth, while remembering different women he has been with. Not only numerous mistresses, but also women with whom he has had other forms of relationship; his three daughters, his aging wife and his mother who suffered a painful death in tuberculosis. "The sleeping beauties" never wake up in Eguchi's presence. They are merely objects for his sublimated eroticism. He fantasizes about how he is making love to them, at one occasion he intends to do it, but refrains from it, feeling guilty about his intentions. On several occasions, old Eguchi fantasies become brutal. He imagines that he is hurting the young women, beating them, raping them, killing them, but most of his time by their side he spends on a devotional admiration of their young bodies, dreaming about past encounters with other women and falls gently asleep.

All this is engulfed in a pensive, dreamlike atmosphere, which occasionally become claustrophobic. Old Eguchi is plagued by a slight suspicion that he is an accomplice in some kind of criminal activity. The place is owned by an absent boss. When a wealthy businessman dies at the establishment, his corpse is discreetly taken away and placed in a hotel room. The drugs administered to the girls seem to be dangerous. Perhaps the girls are there against their will? Nevertheless, despite his doubts old Eguchi returns time and time again. The short novel ends when one of the young women in the middle of the night dies beside old Eguchi and is taken away. The hostess assures Eguchi that the unfortunate incident will not cause him any nuisance. He does not need to be worried and the same night she asks him to return to another "beauty" and fall asleep by her side. "There are more girls than that one". The reader does not know if the girl's death will prevent old Eguchi from revisiting the House of the Sleeping Beauties, but we suspect he will soon die and that the brothel will be shut down.

Reading The House of the Sleeping Beauties is like the encounter with Memories of My Melancholy Whores in many ways an upsetting experience, but its effect is quite different from the one provided by García Marquéz's story. The Colombian's take is far more realistic than Kawabata´s and furthermore has a happy ending. García Marquéz does not create the creepy, chilly and subtly sinister atmosphere of Kawabata´s novel, imbued as it is with distorted aesthetics, emotional callousness and budding anxiety.

Older men sleeping with young naked girls without making love to them actually has a name ̶ shunamatism and has in many cultures been regarded as a way for aging men to revive their life force. When the European brothel culture flourished during the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries, it happened that medical doctors recommended shunamatism as a cure for aging, male patients who was in need to restore their vital fluids.

The denomination originates from the Bible, which tells the story of King David and Avishag, a young woman from Shunem:

King David was now an old man, and he always felt cold, even under a lot of blankets. His officials said, “Your Majesty, we will look for a young woman to take care of you. She can lie down beside you and keep you warm.” They looked everywhere in Israel until they found a very beautiful young woman named Abishag, who lived in the town of Shunem. They brought her to David, and she took care of him. But David did not have sex with her. (Book of Kings, 1:1-4).

Perhaps the most remarkable example of shunamatism is Mohandas Gandhi demanding attractive young women to share his bed with him. Of course, this is a sensitive issue for many of those who, like me, admire the great Mahatma Gandhi for his efforts in preaching and practicing non-violence, tolerance and liberation for nations, women, and men.

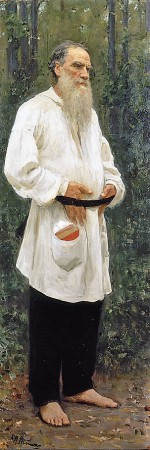

It was when Gandhi in 1906 served as a stretcher-bearer during one of the British wars against the Zulus in South Africa that he decided to make a decisive contribution to the wellbeing of his fellow human beings. To be able to do this he realized that he simultaneously had to strive at disciplining himself by practicing non-violence, patience, honesty and constant self-control. Gandhi, who came from a wealthy and politically influential family of merchants and lawyers, was a searcher and idealist. Early on he tried to improve the conditions of poor, powerless and disconcerted people and by doing so he found inspiration in the writings of Leo Tolstoy. The great Russian novelist was like Gandhi a brilliant man from a privileged family, who late in life was able to transform himself in such a way that many came to regard him as a living saint. However, just like Gandhi, Tolstoy was far from being a secluded, unworldly preacher of good deeds. They were both intense, constantly active and incredibly influential persons, known and respected all over the world.

With his self-sacrificing and temperamental wife, Sofia Andrejevna, Tolstoy had no less than thirteen children, of whom five died before adulthood. The marriage was initially characterized by erotic passion. Just after their intense relationship had been initiated the thirty-four-year-old Tolstoy gave the eighteen-year-old Sofia his diaries, in which he described his previously unusually wide-ranging love life, which among other things had resulted in him having a son with a twenty three year old, married serf woman on his estate. This Timofei Ermilovich Bazykin was never officially recognized by Tolstoy. He died in 1934 after working as a coachman for one of Tolstoy´s legitimate sons, Andrei. Tolstoy also confessed that he in his early youth had seduced a maid servant: Masha, who lived at my aunt’s. She was a virgin, I seduced her, and she was dismissed and perished.”

As his ideas and beliefs became ever more radical, Tolstoy's relationship with his wife deteriorated. He began to discipline himself, becoming a vegetarian and like many self-controlling saints before him Tolstoy also tried to control his sexual urges. He assumed that his sexual desire had so far been exceedingly intense. According to him, he had even allowed it to dominate his life. Tolstoy´s constant urge for sexual intercourse had resulted ridiculous vanity, futile pleasures like dancing and idiotic gallantry, as well an exaggerated care for looks and clothing. He had wasted far too much money and efforts on such deleterious nonsense. Wealth gained from the hard labour of peasants and workers had been thrown away on pleasures that any serious man could be without.

Tolstoy came to consider frivolous love making as the ultimate cause of misogyny and devastating rivalry between people. Tolstoy was a masterful narrator, but his increasingly radical views about abstinence and self-sacrifice broke into his writings, making some of them strange and distorted. Like his Kreutzer Sonata from 1890 in which Tolstoy tells us about how some passengers begin to talk to each other in a train compartment somewhere in Russia (this often happens in Russian novels). Vividly and dynamically Tolstoy recounts the conversation between the narrator, an older merchant, a young bookkeeper, a lawyer and a chain-smoking, middle-aged lady. They talk about gender relations, marriage and love. An obviously nervous man, who initially had listened to the discussions in serious silence suddenly meddles in the conversation and presents the others with a horrific disclosure ̶ he has murdered his wife. The murderer´s troubled fellow passengers disappear one by one, soon the narrator and Pozdnyzhev, the murderer, are alone in the compartment. Pozdnyzhev gives his fellow traveller an intense look:

̶ You may not like to sit here with me, now when you know who I am? If it is so, I'll take my leave.

̶ No, by all means.

Pozdnyzhev then tells the narrator that it was precisely the distorted love based on an uncontrolled sex urge that the train passengers had been talking about, which had driven him to kill his wife. He describes how a time of passionate love, which gave rise to five children, ended when his wife began to use contraception, something that made their love life "even more piggish". The wife became infatuated with a handsome violinist, with whom she practiced Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata, a music so powerful and mentally obsessing that it overwhelmed the two musicians and drowned them in uncontrollable desire. Pozdnyzhev suspected that his wife was lost in her passion for the violinist. He did everything to master his all-encompassing jealousy, but it ultimately made him stab his wife to death, after surprising her and the amorous violinist in flagrante delicto.

Within this dramatically narrated framework, Tolstoy does in Pozdnysjev's mouth put forward his views of fatal sexual desire:

[Man] is only concerned with obtaining the greatest possible amount of pleasure. And who is this? The King of nature – man. You´ll notice that the animals copulate with one another only when if it is possible for them to produce offspring; but the filthy king of nature will do it any time, just as long as it gives him pleasure. More than that: He elevates this monkey pastime into the pearl of creation, into love. And what is that he devastates in the name of this love, this filthy abomination? Half of the human race, that´s all. For the sake of his pleasure he makes women, who ought to be his helpmates in the progress of humanity towards truth and goodness, into his enemies. Just look around you: who is it that constantly is putting a brake on humanity´s forward development? Women. And why is it so? Solely because of what I´ve been talking about.

Pozdnyzhev is lamenting shortcomings of the advancement of medical science, which in our the modern society are thwarting the true nature of man, turning him into a victim of his own whims and desires, while making women into a thing, a mere object of his lust:

Either, with the help of these sharks of doctors, she´ll prevent herself conceiving offspring, and so will be a complete whore, will descend not to the level of an animal, but of a material object, or else she´ll be what she is in the majority of cases – mentally ill, hysterical and unhappy, as are all those who are denied the opportunity of spiritual development.

Four years after his Kreutzer Sonata, Tolstoy published The Kingdom of God is Within You in which he described what he had found by reading of Schopenhauer, the Bible, as well as Christian, Buddhist and Indian mystics and philosophers ̶ namely that we all need to change our lives in accordance with spiritual principles. Only when we abide to God's innermost message ̶ love for your neighbour, self-sacrifice and compassion. Only then can the world and human existence change for the better and we may free ourselves from our imprisonment by property, violence, official religion and oppressive, political power. If each and every one of us honestly tried to live in accordance with the innermost essence of Jesus's teaching, namely that all forms of violence are deplorable, even acts committed in revenge or as self-defence, then we will all finally find ourselves on the right track towards common wellbeing.

The Kingdom of God is Within You overwhelmed Gandhi, here he found the guidelines for his own life. Like Tolstoy, Gandhi minimized his personal needs, dressed as basic as possible, while trying to spread his message as far and wide he gathered disciples around himself, became strictly vegetarian, deeply religious, and became a political agitator with a strict non-violence agenda and at the same time he abstained from sexual intercourse.

To my surprise, I have during conversations with friends who are Catholic priests found that several of do not mind at all talking about sensitive subjects related to sex and the intimate intercourse between men and women. Often they are quite well informed about such things and often reflect on them. As one of them confessed:

̶ If you are denied something, your thoughts are far too often taken up by just that.

Gandhi had no difficulties in living simply and poorly, it was sexual abstinence that plagued him. He developed a variety of complicated rules and regulations for self-discipline, while he at the same time engaged in embarrassing and detailed discussions about sexual intercourse, constantly preaching to others that they should refrain from such activities:

It is the duty of every thoughtful Indian not to marry. In case he is helpless in regard to marriage, he should abstain from sexual intercourse with his wife.

Gandhi put his sexual restraint to test, a behaviour that worsened after the death of his wife in 1944, though his strange behaviour had already begun in the 1910s. At first he slept in the same room as other women, while his wife was present. Then he started to sleep in the same bed with different women. Soon Gandhi demanded that his bed companions like him had to sleep without clothes and they gradually became younger and younger. Gandhi did not have sexual intercourse with any of his female bed companions, explaining that his behaviour was founded on his intention to constantly strengthen his self-discipline. Furthermore, he did not at all carry out in the hidden. On the contrary, he spoke widely about them, spreading his theories through books and articles. Jawaharal Nehru, Gandhi's close collaborator and India's first prime minister, became deeply concerned about Gandhi's preaching about sex and abstinence, finding his friend´s and mentor´s sleeping arrangements to be utterly strange, indeed "abnormal and unnatural." His sexual experiments prompted several of Gandhi's closest colleagues to leave him and two chief editors of the newspapers, which he used to publish his articles, refused to include those articles that exposed his odd views of sexuality and threatened to resign if Gandhi continued to insist that they had be published.

The problem with this mild, tolerant man was that he demanded that people in his environment should live in accordance with his strict chastity rules. While Gandhi slept naked with young women, he demanded that men and women who lived around him would sleep apart from each other. If they felt overwhelmed by sexual desire he recommended them to immerse themselves in cold water.

Gandhi's wife Kasturba often despaired about her husband's moral rigor: "You try to turn my boys into saints, even before they have become men." Gandhi's eldest son became a victim of his father's rigidity. Like other sons of great men, Harilal Gandhi lived shadowed by his father. He turned into a dapper man, outfitted in expensive tailor-made, imported suits, while he gambled and drank. By the end of his unhappy existence Harilal converted to Islam. Five months after his father´s assassination he died of tuberculosis in a municipal hospital, forgotten and neglected.

Apparently did Mahatma Gandhi suffer from a blindness that seems to affect other practitioners of shunamatism. In spite of preaching non-violence, humility, tolerance and compassion, Gandhi seemed to have neglected that his austere views of human existence put high demands on his environment. This while he himself lived according to his own rules. For sure, he was the undeniable Father of a Nation, though he had difficulties in applying that role to his own fatherhood and since he also was a shunamatist I cannot help wondering if Gandhi really could, or even tried to, imagine the feelings of the young women he chose to be his bed companions.

And Paris? Did Che Guevara's opinion that without the Cuban revolution, Latin American writers of magic realism, would have been "nothing more than a bunch of vagabonds rambling around in Paris." I do not know, but Paris seems to have had a transforming impact on many authors, not the least when it comes to “sexual liberation” and perhaps even on the development of a cynical masculine view of sex.

Henry Miller, arguably the most important literary exponent of male, sexual desire, did after a visit to Hôtel Orfila, where the Swedish literary giant Strindberg experienced his so called inferno crisis, state that:

It was no mystery to me any longer why he and others (Dante, Rabelais, Van Gogh, etc., etc.) had made their pilgrimage to Paris. I understood why it is that Paris attracts the tortured, the hallucinated, the great maniacs of love.

Adams, Jad (2011) Gandhi: Naked Ambition. London: Quercus Books. Borón, Atilio (2008) “La derecha contraataca” in El Pais, 29 de marzo, De Monte, Boyé Lafayette (1996) NTC´s Dictionary of Mexican Cultural Code Words. Chicago: NTC Publishing Group. García Marquéz, Gabriel (2006) Memories of My Melancholy Whores. New York: Vintage. García Marquéz, Gabriel (2006) Strange Pilgrims. New York: Vintage. Halford; Macy (2010) ”The Nobel Is the Best Revenge” i The New Yorker, October 7. Kawabata, Yasunari (1969) House of the Sleeping Beauties and Other Stories. New York: Kodansha International. Miller, Henry (2001) Tropic of Cancer. London: Penguin Modern Classics. Mostashari, Firouzeh (2010) From the Ideal to Femme Fatal: Tolstoy’s Thoughts on a Peasant Woman https://russiantheatrefest.yolasite.com/research.php Padilla, Heberto (1984) Heroes are Grazing in My Garden. New York: Farrar Straus & Giroux. Tolstoy, Leo (1988) A Confession and Other Religious Writings. Tolstoy, Leo (2008) The Kreutzer Sonata and Other Stories. London: Penguin Classics. Tolstoy, Leo (1988) A Confession and Other Religious Writings. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics. Vargas Llosa, Mario (1971) García Marquéz: historia de un deicidio. Barcelona: Editorial Seix Barral. Vargas Llosa, Mario, et.al. (1996) Manual del perfecto idiota latinoamericano. Barcelona: Plaza & Janés.