THE MALE QUEST: Heart of Darkness and Moby Dick

A few years ago, in a Hässleholm, far from the rest of the world, I asked some of my students to read Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness, as attentively as they could. They participated in a study programme called "international relations" and I wanted to confront them with the how the prisms of great books may produce several different images. How our emotions interpret books, movies or music, depending on the occasion and the circumstances during which we are confronted with them.

I have read Heart of Darkness several times and each time it has come forth as a different book. William Faulkner was once asked about the three novels he would like to recommend to a student.He replied: "Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina, Anna Karenina". I assume Faulkner meant that the novel had been different every time he read it.

For me Heart of Darkness constantly appear in new and different guises. For example, I wrote these lines in Rome just before I left for our house in Bjärnum, Sweden. After a day in the forests of Göinge I found that my wife had put a CD in the car on which the Swedish actor Max von Sydow read Heart of Darkness. I listened and found that I had forgotten the detailed landscape descriptions and the scattered mind games in the beginning of the book. I also noticed the different layers of storytelling - how an unknown sailor recalls how Marlow tells about his Congo experience to a group of his friends. As a young man, I read the novel as an adventure story about how one man ended up in a strange world; with threatening jungles, incomprehensible savages and crazy colonizers, while nature´s barbarizing influence infected and wiped out the thin veneer of “Western culture".

Then I came to study anthropology and found that Heart of Darkness was a story about Westerners´ meeting with The Other. About a yearning for adventure born out of youthful reading of exciting tales from different centuries and places. How Marlow, an explorer of exotic places and the human mind, to a spellbound circle of friends on the rear deck of a yacht anchored on the River Thames, related his experiences in a mysterious and alien world. The anthropologist is not only a provider of scientific information from different societies, but also an adventurer who often single-handedly has penetrated an unfamiliar sphere of thoughts and behaviour and like a writer s/he conveys her/his exclusive impressions to us. Not for nothing did one of the pioneers of modern anthropology, Bonislaw Malinowski, who like Conrad had travelled among Pacific and Indonesian islands, state that it was his wish to be “the Joseph Conrad of anthropology”.

I saw Apocalypse Now, and once again read Heart of Darkness, the main inspiration for the movie. Now I saw the novel in the light of the Vietnamese madness. How the West's insatiable greed and exploitation of people broke down and corrupted their victims, altering a culture and social interactions, which had developed in harmony and interaction with an admittedly often cruel and merciless nature, but still consistent with our essential human nature, marked as it was by our pursuit of happiness and fellowship with our neighbours and next of kin. How war and greed break down both victims and perpetrators. Every violent intervention in people's lives tends to create a devastating chaos.

I read that while Coppola shot his film in a region of the Philippines a quiet little town changed into something completely different. The huge movie team´s requirement of workers had created a boom and some of the lately, relatively wealthy urban residents did, according to the authorities, indulge in rampant drunkenness and fornication. After Coppola and his team had left the island a Minister of Social Security complained:

Some gays with the crew fell in love with the young macho boatmen, and then it went to much younger boys, down to nine, ten, eleven years old, and the whole town got into it. By 1989, a flourishing trade in boy prostitution tacitly supported by the community had brought economic advantages to the children and their families.

While in high school I worked one summer as a waiter at a seaside hotel where I met with a Senegalese, who worked as dishwasher. He was an avid reader and when I asked him which he considered to be the best African novel, he declared that Le Regard du roi had changed his view of the world. "The King's gaze," was written by Camara Laye, a writer born in what was then the Haute-Guinée, French Guinea. I read the English translation The Radiance of the King and became impressed. The novel tells the story of a white man in an unnamed African country. In despair due to gambling debts and contempt from bigoted colonizers Clarence is searching for a legendary king residing in the heart of the African continent. Imprisoned by his own arrogance Clarence assumes himself be significantly more important and wronged than he actually is and assumes that the mighty ruler, who in secret appears to control life in the country, will be happy to take him into his service. Clarence caught a glimpse of him during a procession in the capital, but when he is trying to get an audience in the royal palace he is told that the king had left for the interior. In the company of a beggar and two mischievous boys, Clarence starts his quest for the ever elusive king and they find themselves in an increasingly surreal landscape. During his trek into the unknown, Clarence is forced to reveal himself from one after the other of his prejudices and delusions, until he naked and confused is sold as a slave and ends up by the king's court in the interior of Africa's jungles. The king proves to be a black youth surrounded by a remarkable radiance. Humiliated and destitute Clarence crawls in the dust before this unspoiled, young monarch, who raises him up and presses the humiliated white man to his chest. Clarence can hear Africa's heart pounding.

Obviously, Camara Laye had read Kafka, the Bible and Joseph Conrad. Clarence is like K in Kafka's novels, a seeker, but unlike K Laye´s downtrodden hero reaches the goal of his quest, which is rooted in the life-giving, African earth from which all of us humans originate. Camara Laye provided Heart of Darkness with an African angle. Without mentioning this novel he turned its message upside down. Conrad´s tale may be interpreted as uncivilized Africa breaking down the Westerners who dare to penetrate the continent, changing them into greedy brutes. Like the maddened ivory trader Kurtz, colonizers are in the danger of losing the varnish of the “enlightened and decent” culture that for centuries have been part of their self-image. Although even if their state of "higher development" initially gave the Westerners an advantage over the people they colonized, this sense of superiority eventually brutalized them. They mixed their self-righteous arrogance and greed with the oppressed peoples´ "crudeness" and thereby became far more brutal than the "savages" they had subdued. In Laye´s novel all this is reversed. The white hued Clarence becomes ennobled through an acceptance of his African origins - the living heart of Africa, its unadulterated humanity.

My good friend Michael, who was my supervisor at the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, had been attracted to Heart of Darkness because its fame of being an effective attack on colonialism in general and especially as a battle cry against the unrestrained exploitation of people in Leopold the II´s Congo. The so-called Congo Free State belonged between 1885 and 1908 to this Belgian monarch as his personal property and under his rule between 8 and 30 million people were brutally killed, depending on the population estimates. With astonishment Michael told to me:

- I recently read Heart of Darkness and became appalled. The novel is outright racist! Honestly, I do not understand why it has been hailed as a compassionate defence of the Congolese while challenging Leopold's ruthless exploitation. The protagonist considers black people to be inferior beings.

Michael´s reaction might effortlessly be confirmed. Conrad was not opposed to colonialism. However, according to him it had to be practiced virtuously, not as it was applied by the Russian rulers of his native Poland, or prompted by the murderous greed that motivated the Belgian presence in the Congo. Conrad considered his adopted Britain as a guardian of morality and civilization and did not object to the British Empire. However, regarding black people he appears to have been consumed by a mixture of terror and fascination, largely coloured by the evolutionary racism of his time.

Michael is far from being the only reader who has been distraught by the novel's obvious racism. It is understandable to be disturbed by Conrad's description of Marlow´s stoker aboard the riverboat he steers along the Congo River:

… and, upon my word, to look at him was as edifying as seeing a dog in a parody of breeches and a feather hat, walking on his hind-legs […] He ought to have been clapping his hands and stamping his feet on the bank, instead of which he was hard at work, a thrall to strange witchcraft, full of improving knowledge. He was useful because he had been instructed…

The Nigerian writer and university professor Chinua Achebe did in a famous lecture define Heart of Darkness as an "offensive and deplorable book", expressing his regret that such an openly racist, albeit well-written and multi-layered, novel is being studied with approbation in schools and universities.

Conrad saw and condemned the evil of imperial exploitation but was strangely unaware of the racism on which it sharpened its iron tooth. But the victims of racist slander who for centuries have had to live with the inhumanity it makes them heir to have always known better than any casual visitor even when he comes loaded with the gifts of a Conrad.

Possibly Conrad could be defended by the fact that he does not hide fear and alienation. Marlow does not only talk with occasional derision about the Congolese natives, but also merciless criticizes the colonists, with ironic distance ruminating about their ridiculous, bloated complacency and insensitive cruelty. Marlow is a stranger, both among colonialists and natives. When the steamboat chugs along the jungle beaches Marlow is dismayed by the primeval forest´s vastness and the uninhibited behaviour he notices among its inhabitants, a world completely foreign from anything he had expected:

The earth seemed unearthly. We are accustomed to look upon the shackled form of a conquered monster, but there -- there you could look at a thing monstrous and free. It was unearthly and the men were .... No they were not inhuman. Well, you know that was the worst of it -- this suspicion of their not being inhuman. It would come slowly to one. They howled and leaped and spun and made horrid faces, but what thrilled you, was just the thought of their humanity -- like yours -- the thought of your remote kinship with this wild and passionate uproar.

Apparently, Conrad does not despise of the Congolese. On the contrary, he expresses some kind of kinship with them. He is reluctantly attracted by their "spontaneity", their openness. The steamy, stifling jungle atmosphere and its "savages" appear to be more vivid and attractive than a Brussels Conrad called "a whited sepulchre". When he describes the stoker as a trained dog it might indicate that Conrad regretted "civilization´s" devastating impact on unrestrained emotions.

Let the fool gape and shudder - the man knows, and can look on without a wink. But he must at least be as much of a man as these on the shore. He must meet that truth with his own true stuff - with his own inborn strength. Principles won't do. Acquisitions, clothes, pretty rags - rags that would fly off at the first good shake. No; you want a deliberate belief.

Marlow, Conrad's narrator, is obviously a personification of his own experiences as a captain in the oppressive Belgians´ service. Conrad, who had been mistreated in Congo and became seriously ill, felt alienated from everything, just like Marlow:

We were cut off from the comprehension of our surroundings; we glided past like phantoms, wondering and secretly appalled, as sane men would be before an enthusiastic outbreak in a madhouse. We could not understand because we were too far and could not remember because we were travelling in the night of first ages, of those ages that are gone, leaving hardly a sign—and no memories.

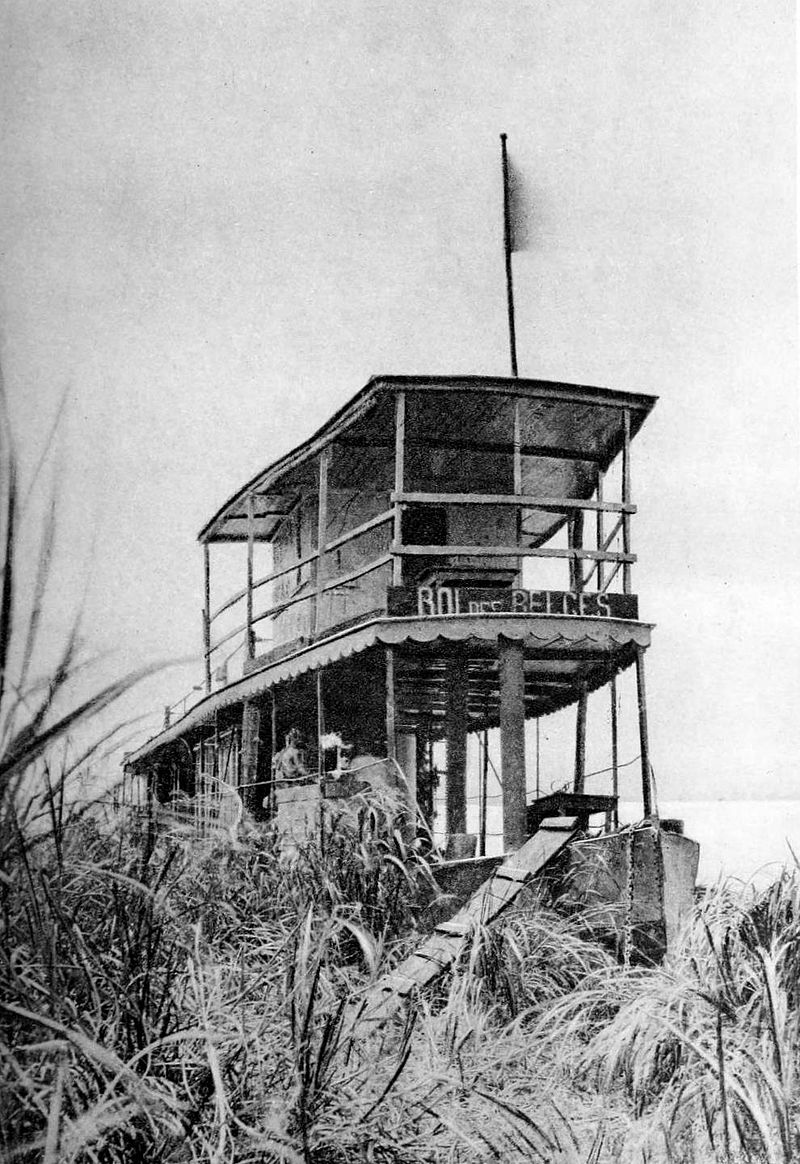

I was quite perplexed when I a few years ago spent some time in Kinshasa. The vast slums, dirt roads, incomprehensibly dilapidated government buildings, traffic congestion, heavily armed guards and soldiers who asked for, or rather - demanded money. People everywhere, except during the dark evenings in the diplomatic quarters, most of them very friendly. The constant concern born out of being a single white person in this throng of poor people, though my Congolese hosts followed me everywhere and did their best to make me feel safe, have a good time in their company and get a good impression of their city. The Congolese rumba, the dancing in the evenings, poverty and chaos. I remember how the plane approached its goal above trackless jungles with villages clustered by brown tributaries, as well as the huge, leisurely moving Congo River. All this must have been even more remarkable in Conrad's time, when his steamboat chugged along between beach embankments, among huge logs, hippos and crocodiles:

Trees, trees, millions of trees, massive, immense, running up high; and at their foot, hugging the bank against the stream, crept the little begrimed steamboat, like a sluggish beetle crawling on the floor of a lofty portico.

The misery of the small, shabby colonial settlements, where violence and ruthless exploitation revealed its ugly face, where people were beaten and exploited until they became mere, starving shadows of their former selves:

They were dying slowly—it was very clear. They were not enemies, they were not criminals, they were nothing earthly now — nothing but black shadows of disease and starvation, lying confusedly in the greenish gloom. Brought from all the recesses of the coast in all the legality of time contracts, lost in uncongenial surroundings, fed on unfamiliar food, they sickened, became inefficient, and were then allowed to crawl away […] glancing down, I saw a face near my hand. The black bones reclined at full length with one shoulder against the tree, and slowly the eyelids rose and the sunken eyes looked up at me, enormous and vacant, a kind of blind, white flicker in the depths of the orbs, which died out slowly.

.jpg)

Gender research has examined "adventure stories" like Conrad's novel, Stanley's jingoistic descriptions of his expeditions, and above all H. Rider Haggard´s and Edgar Rice Burroughs´s thrilling, male-dominated stories about how white men penetrates perilous jungles to come across forgotten kingdoms in the depths of Africa. Such stories are obviously masculine fantasies about a feminized Africa, like a prostrated woman's body awaiting a white male to penetrate and tame her, robbing her of pride and dignity. Racist and misogynistic stereotypes ravage unbound in depictions of naked, black women and untamed wilderness, "lush, fertile and mysterious."

Is this typically male? Overgrown, testosterone fuelled bucks embarking on adventures into the unknown, while white women are depicted as more practical, moving around home and children, writing books, which with sharpened eyesight and psychological depth depict everyday problems. Probably a generalization. Anyone might enumerate adventurous, fearless ladies who have embarked on what the English denominate as The Quest.

I once read a thought-provoking book by Elaine Showalter, Sexual Anarchy, in which she pointed out that many male writers by the end of the 1800s felt threatened by a growing number of writing and reading women. At that time, three quarters of all published novels in the US were written by women. In the smoke and whiskey-soaked gentlemen's clubs and officer messes on both sides of the Atlantic self-declared, virile gentlemen dreaded that "male" virtues were retreating from contemporary literature. Did not this radical feminisation of the written word represent a danger to young men growing up? Accordingly, “boys´” literature received a major boost and mannish adventure seekers appeared in books by Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, Conan Doyle, G.A, Henty and H. Rider Haggard, to mention some of my favourite authors during my literature devouring youth. Not least Heart of Darkness was written for a male audience and published as a serial in Blackwood's Magazine. Conrad remarked:

One was in decent company there. And had a good sort of public. There isn´t a single club and messroom and man-of-war in the British Seas and Dominions which hasn´t its copy of Maga [the popular name of Blackwood´s Magazine].

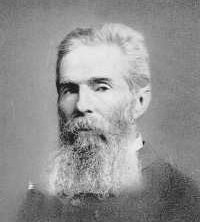

What is Heart of Darkness all about? Does the novel have a clear-cut message? Does it reflect the views of the author? The American literary critic Harold Bloom wrote that Heart of Darkness has been analysed and interpreted more than any other individual, literary work, something which is due to Conrad's "unique propensity for ambiguity." A reader of well-written "seeker" novels, like Conrad's Heart of Darkness, or Kafka's The Castle, is confronted with a variety of clues to how the world might be considered. Trails that run in different directions - into the world or into the reader. Heart of Darkness brought me to one of the truly great "seeker novels", which also is told by a person other than the author, like in Conrad´s story he is a sailor who remembers a fatal adventure in his youth, a life-changing experience he probably shared with the author. Central in both novels is a ship within a macho world and with a mixture of mysticism, realism and alienation both novels drill down deep into human existence and madness, the mystery of nature and our place on earth - Herman Melville's strange Moby Dick or The Whale.

I recently saw John Houston's film version from 1954 with Gregory Peck in the role as the crazed Captain Ahab, who with unbridled vindictiveness over the oceans pursues the immense, white sperm whale that has swallowed up his leg and damaged his mind. It has been said that Peck was out of place in his role as Ahab, though I found him to be quite impressive and I reread the novel to check my positive impression of the movie. Last time I read it I was twelve years old. I know this because it is written in it that my father gave it to me as Christmas present.

I found now that Moby Dick can be read as a fairly straightforward adventure story and that the more than six hundred pages can easily be shortened by two thirds, without losing any of its dramatic progress and the essential episodes, which are told with masterful drama. When I read the novel I could not understand how a twelve years old boy with such ease could overcome the philosophical and scientific reflections, written in a language alluding to Shakespeare, Milton and the Bible. Particularly considering that at that age I was a very diligent reader, sinking deep into the books.

My father probably gave me the book since he knew that I, mainly through my grandfather's influence, was fascinated by salty tales of the sea and large sailing ships. And what kid is not overcome by awe at the thought of the secrets of the dark depths of the sea? Even as a little boy I was appalled by the bloody slaughter of the mighty whales. During the customary February breaks from school, the decrepit assembly hall of the town´s high school was the scene of screening of nature – and fairy tale movies. In the dusky light from windows that had been feebly hidden by poorly drawn curtains and to the sound a rattling projector flickering movies about foxes and lions were presented and I particularly remember a colour film about Norwegian whale hunt. Floating factory ships processed bloody whale carcasses that were winched on board ship decks, slippery with blood. These huge, peaceful creatures had been helplessly harpooned while their blood catapulted high up in the sky. It was like a horror movie, to be forced to witness this wanton slaughter to the accompaniment of a dry voice over.

Many years later, I took my then eleven years old daughter to the American Museum of Natural History in New York and we were both taken by the colossal Blue Whale suspended over our heads in one of the halls, but Janna had sleepless nights after being confronted with a diorama, which portrayed how a sperm whale somewhere in a deep-sea trench struggled with a giant squid. I must have been younger than her when I saw the skeleton of a Blue Whale that some funfair company exhibited in the town square in Hässleholm. I remembered that when I last year found myself on a beach by the Caribbean Sea was reading Lázló Krasznahorkai´s eccentric novel The Melancholy of Resistance, which describes how the presentation of a stuffed whale in a small Hungarian town triggers off riots, intimidation and abuse of power. On the book's cover was a picture of a humpback whale and when I looked up I could imagine how shoals of such whales was moving under the sea far out beyond the horizon.

Every year, between December and April, thousands of humpback whales appear in the warm waters along the American Atlantic coasts, after traveling from the Arctic Ocean around Iceland, Greenland and Canada. Many seek out the Samaná Bay in the Dominican Republic. In small boats you may circle around these immense, but strangely peaceful sea creatures and also through probes, lowered into the water, listen to how they talk to each other. Occasionally, a whale my jump up out of the water, high up in the air, but always away from the boats, something that does not prevent the whales to approach them and raise their noses, often covered with barnacles, right next to the gunwales. My wife, who does not like to travel by boat over deep water, described the tranquillity that reigns around the whales´ powerful presence. She and my daughters have experienced this twice, but I have never had such an encounter. My only experience with marine mammals was then a shoal of dolphins closely followed a small boat that took me to the town of Livingston in Guatemala, it was unforgettable but probably not as powerful as being close to the whales in the Samaná Bay.

In his book The Cruise of the Cachalot Frank T. Bullen wrote about how humpback and sperm whales care for their calves. A female humpback whale had been harpooned outside the Tonga Islands:

Close nestled to her side was a youngling of not more, certainly, than five days old, which sent up its baby-spout every now and then about two feet into the air. One long, wing-like fin embraced its small body, holding it close to the massive breast of the tender mother, whose only care seemed to be to protect her young, utterly regardless of her own pain and danger. If sentiment were ever permitted to interfere with such operations as ours, it might well have done so now; for while the calf continually sought to escape from the enfolding fin, making all sorts of puny struggles in the attempt, the mother scarcely moved from her position, although streaming with blood from a score of wounds. Once, indeed, as a deep-searching thrust entered her very vitals, she raised her massy flukes high in air with an apparently involuntary movement of agony; but even in that dire throe she remembered the possible danger to her young one, and laid the tremendous weapon as softly down upon the water as if it were a feather fan.

So in the most perfect quiet, with scarcely a writhe, nor any sign of flurry, she died, holding the calf to her side until her last vital spark had fled, and left it to a swift despatch with a single lance-thrust.

Like many other contemporary whaling writers, Bullen respects the whales, particularly sperm whales, the big toothed whales that unlike other whales often attacked their tormentors. Bullen´s book describes several epic battles against sperm whales and the great risks whale hunters ran when their small boats, alone in apparently endless oceans, harpooned these desperate, giant mammals. Despite dramatic depictions of broken boats, adrenaline-fueled pursuits and aggressive sperm whale males, a reader cannot fail to be dismayed by the bloody slaughter, especially as Bullen describes how whalers first tried to kill calves in order to attract their worried mothers and then speared them so the mighty males would swim up to defend their wounded mates.

Bullen´s book was published in 1898, but describes the author's experiences twenty years earlier. It was hailed by Rudyard Kipling: "It is immense - there is no other word. I've never read anything that equals it in its deep-sea wonder and mystery." I am inclined to agree. Through its forthright language and ingenious narrative style The Cachalot is one of the best sea stories I have read. It describes a journey of self-realization, telling how the orphaned, totally destitute Bullen is confronted with the brutal regime, the heavy, dangerous work and confinement on the whaling ships that between two and three years sailed all over the world´s oceans, in search of sperm whales. Eventually, Bullen becomes accustomed to the raw life aboard and is promoted to second mate.

By the beginning of the last century The Cruise of the Cachalote became required reading in several American schools and the gung ho president Theodore Roosevelt recommended the book as excellent reading for educating boys to men. American “whale men” became role models for virile machos and even symbols for the young, profit-oriented American nation. At first the whaling industry was an extremely lucrative business, the pure whale oil was a superior lubricant and excellent lamp fuel, while musk and ambergris were coveted by the perfume industry. The practical approach and inventiveness that characterized virtually everything associated with whaling, combined with the physically demanding and exceedingly strenuous work meant that sailors, mates and captains not only had to be experts at handling large full-rigged ships, but also ready to expose themselves to the dangerous whaling, the taxing efforts to slay the mighty animals from small boats and then salvage and prepare the precious oil. This exciting activities turned whalers into proletarian model workers. Already in 1834 the author Joseph C. Hart praised the whalers as "a bold and hardy race of men."

Descriptions of the hard life at sea fitted like hand in glove to the ideal of masculine hands-on adventure stories that were greatly appreciated at the time before World War I. It was a hard life that welded a macho collective through constant dangers and hard work. Descriptions of life at sea was generally free from deep psychological analysis, based as they were on robust experience. Probably did those storm whipped, word stripped tales influence important forerunners of modern literature. Hemingway appreciated the energetic books on whaling and Faulkner's fascinating The Bear in his collection of short stories Go Down Moses, can be read like a Moby Dick transferred to the American wilderness.

Walt Whitman is in a poem, Song of Joys, included in his mighty Leaves of Grass, extolling the arousing effect whaling had on its practitioners, not unlike the enthusiasm that Hemingway showed bullfights:

O the whaleman's joys! O I cruise my old cruise again!

I feel the ship's motion under me, I feel the Atlantic breezes

fanning me,

I hear the cry again sent down from the mast-head, There — she

blows!

Again I spring up the rigging to look with the rest — we descend,

wild with excitement,

I leap in the lower'd boat, we row toward our prey where he lies,

We approach stealthy and silent, I see the mountainous mass,

lethargic, basking,

I see the harpooneer standing up, I see the weapon dart from his

vigorous arm;

O swift again far out in the ocean the wounded whale, settling,

running to windward, tows me,

Again I see him rise to breathe, we row close again,

I see a lance driven through his side, press'd deep, turn'd in

the wound,

Again we back off, I see him settle again, the life is leaving him

fast,

As he rises he spouts blood, I see him swim in circles narrower

and narrower, swiftly cutting the water—I see him die,

He gives one convulsive leap in the centre of the circle, and then

falls flat and still in the bloody foam.

However, everything was not an exciting drama. Week after week, whalers could sail across the vast oceans without sighting any prey, or lying idly in numbing doldrums, suffering from thirst and scurvy. The windowless cabin of the crew "before the mast" smelled of sweat, mildew, moisture, and airless confinement, "there was a rainbow-coloured halo round the flame of the lamp, showing how very bad the air was." Here the sailors slept in shifts while they waited to be called up to their two-hour night shifts. During violent storms water trickled or gushed into the decks below, where it mixed with vomits and whale oil, while the men were called up into the rigging, salvaging and furling the huge stretched, bulging or violently flapping sails. Otherwise, the nights could be devoted to flaying the whales from their fatty blubber, which was cooked on the deck in huge pots and stored in barrels, something that must be done in haste since shoals of sharks feasted on the whale carcasses, which were lashed firmly along the ship's sides. The stench was thick and fat from slaughtered whales seeped in everywhere where it fattened cockroaches, lice and fleas, which seemed to disappear in chilly climes, where the sailors instead suffered from scorching humidity and icy cold. However, the vermin had only gone into hibernation just to be crawling all over the place as soon as the ship returned to the Tropics. The rats were not such a big plague since they were taken care of by ship´s cats. Cleanliness was paramount on every whaling ship, everything was constantly washed and scrubbed. This was also a tactic to keep the men going, ennui and confinement could otherwise lead to fights and mutinies.

Along with dirt, difficulties and dangers, American whaling men suffered under a rigidly organized and oppressive hierarchy, which devastated their independence. Tyranny was considered to be necessary for maintaining the discipline. The complicated management of sailing ships, combined with the hunt and slaughter of whales, demanded that all activities of the sailors´, as well as those of their officers, had to be coordinated in every detail. Each protest and deviant behaviour was struck down with fierce ruthlessness.

No wonder that many Pacific natives suffered when humiliated and hitherto subjugated men were let loose on their islands. Melville writes in his autobiographical novel Typee how whalers subjected Polynesian women to “every species of riot and debauchery”. While aboard the ships strong bonds of friendship were forged between the men. Occasional long periods of peace and calm made it possible for several of them to devote themselves to reading, journal writing and various kinds of handicrafts, of which bone carving and so called scrimshawing, i.e. engraving sperm whale teeth, were popular pursuits. Melville told in his original manner how whalers were able to create correct images of whales, contrary to established artists who could not study these animals in situ, but were obligated to depict bloated carcasses that had been washed ashore. Melville gave a description of an amputee beggar in London, an old whaler who offered his engraved whale teeth for sale. Melville praises those detailed depictions of whale hunts skilfully recreated by barely educated whalers as being far superior to those made by acknowledged artists and academics.

Moby Dick is an extraordinary novel born out of the brutal world of whaling, which at the same time is described as strangely romantic. Pequod, with its crew of hard working men from all over the world under the command of the obsessed Captain Ahab, who knows how to play at their trapped passions and fears, becomes a symbol of the US with its motley crew of citizens travelling towards a distant future, where wealth and money finally will solve all problems, just like the spermaceti oil and ambergris in Pequod´s cargo hold one day will be converted to gold in Nantucket's harbour - something that never happens.

Pequod mirrors the pioneers' covered wagons making their way westward in search of new land and gold, while the bison and indigenous people were slaughtered along their path. Railways and huge cities were built, mines were dug, fortunes heaped, while people from around the world were drawn to the new land, fought with each other and under appalling conditions shipped enslaved individuals across the ocean to work on their plantations. Many Americans were trapped in a dream of a better world beyond the horizon, enclosed by their own distorted ideas and hopes. While creating a world of democracy, celebrating personal freedom, most of them nevertheless remained imprisoned by a myth about their grandeur and uniqueness.

Melville and several other authors writing about the whale hunt seem to be remarkably exempt from intolerance and racial prejudices. Some racist brawls are mentioned by almost all them, though described as anomalies. Melville tells that his main protagonist’s best friend is the heathen, grotesquely tattooed Polynesian Queeqeg, while Bullen´s protector, role mode and friend is the huge Mr Jones, a former slave from Cameroon. Both Bullen and Melville declare that their frequent intercourse with people from diverse cultures and corners of the world has taught them not to judge people on the basis of beliefs and skin colouring, but on their behaviour, honesty and friendship, something that made "culture" and "religion" irrelevant abstractions. Melville´s tolerance and compassionate vision permeates much else that he wrote. I have read his short stories and especially The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids is impressive as it contrasts an orgy of gluttonous over-eating at a Gentleman's Club in London with the devastating factory work that degrades women in an American backwater. The story convincingly envisages the ruthless exploitation and contempt that women have endured throughout the millennia. A maltreatment that first began to be seriously observed and partly amended during the last century. Early on, Melville understood how women's life cycles, their physical well-being, were threatened by the slavery of machine culture and rampant machismo. How profit hunger prevented women from living a life of free choices, as independent individuals. Insights that did not prevent Melville from being a house tyrant and wife beater.

I am surprised that this and other short stories by Melville, which foreshadow Kafka with fifty years, have not received more attention, while almost every punctuation mark in his Moby Dick has been commented on and interpreted. Nevertheless, by the end of the 19th century Melville and his mighty whaling saga were almost unknown, and if mentioned Melville was usually considered as a failed writer, a parenthesis in American literary history. Nevertheless, eventually the titanic Moby Dick rose up from the depths and made its presence felt all over the literary spectrum.

As in Kafka's stories and novels, Melville's depiction of life on a whaling ship is realistic and tangible, yet it is brim-full with strange symbolism, which might be interpreted in several alternative manners. Melville can unexpectedly immerse his reader in encyclopaedic descriptions, break out in romantic depictions of nature, or breathlessly describe thrilling events, constantly keeping us aboard his ship, like when you are being forced to go astray among Kafka's office corridors, or be locked up in his cramped rooms, or feverishly accompany Raskolnikov on his wanderings within a frozen Petersburg. In all its unwieldiness Moby Dick remains “the great American novel”. The Quest above all others. The search for and intended killing of the giant whale remind of how US rulers often assume that if a Stalin, a Hitler, a Bin Laden, a Saddam Hussein, or an Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi would be killed all problems will be solved. Strife and struggle are the optimal solutions. Most of us are like the captive crew of Pequod, blindly obeying their obsessed captain, not realizing that the pursuit of and the fight with the white whale is nothing more than a prolonged battle with themselves and the powerful, unlimited nature surrounding them. A struggle that results in the final defeat of them all.

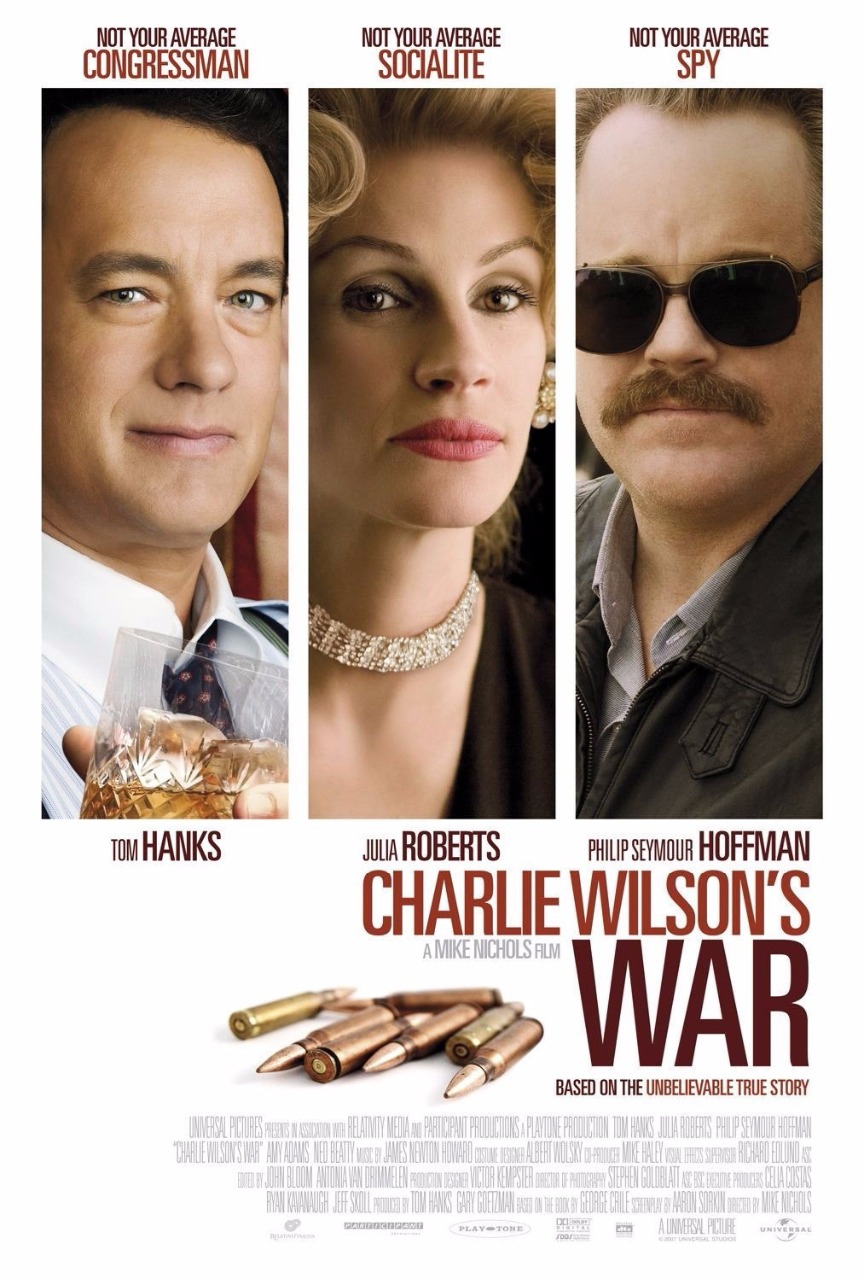

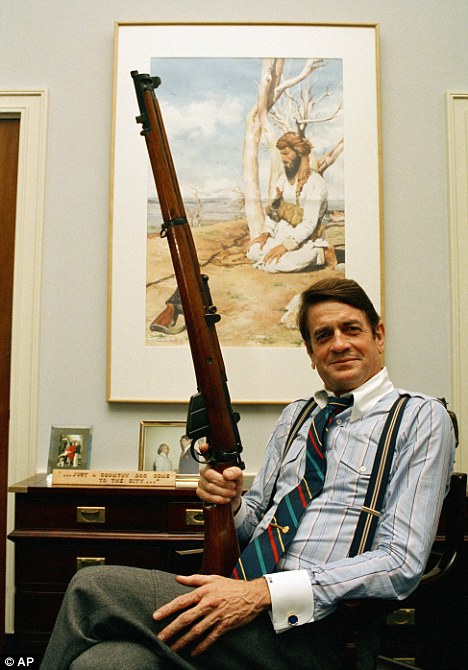

While I with increasing fascination read Moby Dick, I happened to watch the movieCharlie Wilson's War about the maverick, partying, cocaine-snorting, women charmer and Congressman Charles Wilson, who unexpected adopted the Afghan struggle against the Soviet Empire as his main project and managed to ensure that CIA funds for covert arms purchases multiplied, equipping Afghan mujahidinfighters with highly efficient FIM-92 Stingers, which destroyed the Soviet Air Force in Afghanistan and forced the previously unbeaten Red Army on the run, becoming one of the main causes for the collapse of the Soviet Union.

I read more about this and it actually seems like Charles Wilson´s effort was imperative not only to the fall of the Soviet Union, but also for the misery that followed and now is being harvested in Aleppo's hell and Europe's fear of terrorists and immigrants. The obsession of a Captain Ahab may serve as a mirror not only for Charlie Wilson´s engagement, though also its effects that eventually created the madness we now find ourselves in. I shudder and think of Donald Trump, Sweden Democrats and many others.

Nevertheless, I want to state that Charlie Wilson, after all, seems to have been a decent man. He saw the Afghans' suffering under Soviet superiority and helped them to extricate themselves. He also realized the danger of arming the mujahidinand one strength of the movie, as well as the book it is based on, is that they hammer home a message indicating that a single person's dedication can have immense consequences, but also, as Charlie Wilson rightly pointed out - the war was won, while the peace was lost. Trillions of dollars were poured into the Afghan war (the total is estimated at between four and six trillion USD), but when Wilson asked for a few million dollars to schools and education, with the hope that such efforts afterwards, just like before, would be increased and Afghanistan be pulled out of the misery following the war. However, the money flow was hampered. To build and secure peace is obviously much more difficult than waging war. Money for the good of all of us is more difficult to procure than those money sacrificed to greed and armament, the only development assistance that is truly effective.

Enormous efforts were dedicated to the slaughter of whales, as long as their oil was valuable these huge, peaceful creatures were ruthlessly hunted to the brink of extinction. Melville´s Moby Dick did escape, but his model, the mighty Mocha Dick, was killed. The whale hunt subdued, hardly no prey was left and what could be extracted from their carcasses became more or less worthless.

Will Trump win the US election? Will the hunt for terrorists cease? Will Al Baghdadi be killed? Will there be peace on earth? The Quest continues.

Achebe, Chinua (1977) "An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's 'Heart of Darkness'" in Kimbrough, Robert (ed.) (1988) Heart of Darkness, An Authoritative Text, Background and Sources Criticism. London: W. W Norton. Bullen, Frank T. (2001) The Cruise of the Cachalot: Around the World After Sperm Whales. Torrington, WY: The Narrative Press. Cohat, Yves (2001) Whales: Giants of the Seas and Oceans. New York: Abrams. Conrad, Joseph (2007) Heart of Darkness. London: Penguin Classics. Crile, George (2004) Charlie Wilson's War: the Extraordinary Story of the Largest Covert Operation in History. New York: Grove Press. Laye, Camara (1965) The Radiance of the King. Glasgow: Harper/Collins. Melville, Herman (2003) Moby Dick or The Whale. London: Penguin Classics. Melville, Herman (1986) Billy Budd and Other Stories. London: Penguin Classics. Schell, Jennifer (2013) "A Bold and Hardy Race of Men": The Lives and Literature of American Whalemen. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. Showalter, Elaine (1990) Sexual Anarchy: Gender and Culture at the Fin de Siècle. London: Penguin. Whitman, Walt (1961) Leaves of Grass: The first (1855) edition. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics.