THE STRESS MIGHT KILL YOU: Music and hormones

Sooo, be quite ... slow down, take a deep breathe. It´s warm outside. The sun shines from a clear blue sky. A gentle breeze. Windows and doors are open towards the greenery, thin linen curtains are softly wafting. My granddaughter - a small creature, new to the world, beautiful and helpless, rests safely in my arms. Children are miracles. Their existence astounding.

Here is the Swedish-Finnish poet Elmer Diktonius´s image of a small child:

The child in the garden

is a wondrous thing;

a tiny, tiny animal

a tiny, tiny flower.

Like a cat it snuggles by the carnations

rubbing its head

against the stem of a giant sunflower.

Maybe thinks: sun is delicious -

green is grass colour.

Maybe knows: I´m growing!

Little Liv warms my heart, makes me feel that life is strong within me. After all those years my heart is steadily going strong, my lungs continue to move in their rolling rythm.

In my granddaughter there is not the slightest grain of evil. She rests confidently in herself, dreaming unknown dreams. By her there is are no worries about money shortage, unpaid bills, envy, harrowing commitments, responsibilities for everyone and everything. No longing for love and understanding keeps her awake in the nights. She is not whipped by prestige hunt. It is not her that Odin is talking about in the ancient Viking poem Havamal:

The stupid man stays awake all night

and worries about everything;

he's tired out when the morning comes

and all's just as bad as it was.

For me and others, life goes on. Before we fall asleep we sense how a dark future is hovering around our bed. When unease rages in and around us, moments of peace and satisfaction are shortened. Like the beast under the bed, the stress is sharpening its teeth. We cannot handle our losses and shortcomings, our wrecked economy. Fear lingers; of being exploited, threatened or simply forgotten and overlooked. Diseases gnaw within us, external forces are tearing us apart. When I´m threatened by something that the Italians call caos calmo, quiet chaos, or more explicitly - nagging anxiety, I, like most of us, take my refuge to unsustainable solutions. I get rid of problems by trying different attempts to obscure life´s demands. Sometimes I follow the recommendations of the unhappy Swedish poet Dan Andersson:

When those old wounds are hotly tearing

and from loneliness your cheeks are wet with tears;

When your life is just a stone to carry

and your song is grief, like crying cranes astray,

go and drink a whiff of windy autumn,

Watch with me the fading, pale blue sky!

Come, we'll lean against the pasture gate-bars

while those wild geese are flying by.

However, that is no more than temporary relief. Other escape routes from an impossible life project are reading, art, music and blog writing. Though they all lead nowhere, it is impossible to deny that reading, writing and listening to my friends are alleviating anxiety. The Swedish poet Erik Lindegren, explains, in his poem Arioso how we meet "the others" inside ourselves, those who are also me - in the Hindu sense Tat twam asi, तत्त्वमसि, "you are it". Each and every one of us constitutes a part of the universe, within us all breathes the universal spirit, the Brahman:

Somewhere within us, we are always together.

Somewhere within us, our love cannot escape.

Somewhere, oh somewhere,

all the trains have left and the clocks have stopped,

Somewhere within us, we are always here and now ...

Arioso, "airy", is a musical term used to describe when a soloist, in an opera or an oratorio, with orchestral accompaniment expresses her/himself through rhythmic speech. For me, especially chamber music appears to be endowed with an intimate and dynamic character which distracts me from everyday stress and pain. I imagine that music possesses a supernatural force, something beyond all constraints - a Tat twam asi.

Perhaps it was this assumed creative joy that is inherent in music, its connection with something extra-terrestrial, which made the aged Swedish movie director Ingmar Bergman to state that: "Just like Bach, Christ was a philosopher who testified about other worlds than the one we live in.” Bergman compared his own creative force with what he claimed to be Bach's evening prayer:" O Lord, please don´t take my joy away from me."

When I listen to Bach, though maybe even more intensively to Schubert's music, I imagine that the creator of such perfection must have been a happy human being, and in one of his diaries Schubert claimed that “anyone who loves music can never be quite unhappy.” Nevertheless, mind that he wrote "quite unhappy” as if the sadness is constantly present, as a dark background to our lives.

Schubert wrote continuously, despite suffering from financial concerns, love pain, illness and notwithstanding his unrivalled brilliance a dismal feeling of insufficiency. Five years before his death, at the age of thirty, Schubert wrote to his friend Leopold Kupelweiser:

Every night when I go to bed, I hope that I may never wake again, and every morning renews my grief. I live without pleasure or friends.

Chill often penetrates Schubert's tense music, like in his Winterreise , or in his the intense Doppelgänger, in which a quietly developing unease is accompanied by increasingly dissonant chords, which inevitably lead to a final packed with threatening premonitions of a terrifying disaster, which nevertheless is not allowed to blossom. Schubert has an amazing ability to immerse himself in a text and interpret it in a profound, deeply personal manner, something he does with Heinrch Heine's already creepy text:

Du Doppelgänger! Du bleicher Geselle!

Was äffst du nach mein Liebesleid,

Das mich gequält auf dieser Stelle,

So manche Nacht, in alter Zeit?

O you Doppelgänger, you pale comrade!

Why do you ape the pain of my love,

which tormented me upon this spot

so many a night, so long ago?

No wonder Schubert stated that "there is no such thing as happy music." Even music that makes me happy and excited seems to harbour a grain of pain, perhaps because music interprets life, which is actually like that. Schubert explained:

No one understands another’s grief, no one understands another’s joy. […] My music is a product of my talent and my misery. And that which I have written in my greatest distress is what the world seems to like best.

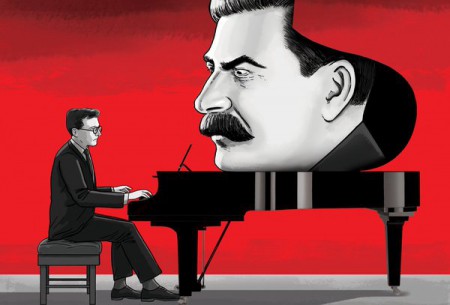

Perhaps he would be in agreement with Dimitrij Shostakovich, another composer whose music I am willing to spend considerable time with. Shostakovich, who in both his life and music seems to reflect a bitter point of view, though nevertheless often quite often humorous and sharp, stated that he had never been happy. Despite his gloomy disposition, Shostakovich could not avoid composing every day and declared that if even his hands were cut off, he would continue to write, even he was forced to compose with a pen between his teeth:

When a man is in despair, it means that he still believes in something. […] The majority of my symphonies are tombstones […] The withering away of illusions is a long and dreary process, like a toothache. But you can pull out a tooth. Illusions, dead, continue to rot within us. And stink. And you can't escape them. I carry all of mine around with me.

Is this a result of the "Russian melancholic soul"? I do not believe in national character, but it cannot be denied that Russian artists generally lived under suffocating oppression. Most of them had lost dear ones to the tyranny. However, some insisted in considering their failures and the abuse they were subjected to as fuel for their art. I recently read a few lines by Boris Pasternak, whose life and literary production was characterized by the constant and often devastating presence of Soviet surveillance and censorship, much of his works were lost in chaos and repression:

In life it is more necessary to lose than to gain. A seed will only germinate if it dies. One has to live without getting tired, one must look forward, and feed on one´s living reserves, which oblivion no less than memory produces.

An assertion that finds an echo in the bitter, but also gloomy humorous Samuel Beckett. Who offers his famous advice in the "novel" Worstward Ho:

Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.

Anguish may thus be regarded as a positive feature insofar as it leads to insight and improvement, perhaps in line with Nietzsche's endlessly cited and generally misquoted eighth aphorism from Maxims and Arrows" in his The Twilight of the Idols and the Anti-Christ: or How to Philosophize with a Hammer:

Aus der Kriegsschule des Lebens. – Was mich nicht umbringt, macht mich stärker. From life´s war school: What does not destroy me makes me stronger.

Insights about positive effects of suffering are offered by various religious writings. Not the least among Christians, suffering may be described as a valuable experience resulting in an increased understanding of the inner meaning of life. Jesus's redemptive suffering is considered as an act of compassion, a reconciliation with God, the power governing our existence. By believing in and following the example of Jesus, we may be able to reinstate our broken bond with God´s Creation. Suffering thus becomes a means of finding God and to understand that faith exists beyond reason and understanding.

Likewise, music is almost impossible to explain - it speaks differently to each and every one of us. The strictly Calvinist Japanese conductor Maasaki Matzuki believes that God speaks directly to us through Bach's music:

With the help of His disciples, God left us the Bible. Into the hands of Bach He delivered the cantatas. That is why it is our mission to keep performing them: we must pass on God’s message through these works, and sing them to express the Glory of God.

Matzuki, who undoubtedly is one of the world's premier interpreters of Bach's music, claims that:

Bach works as a missionary among our people. After each concert, people crowd the podium wishing to talk to me about topics that are normally taboo in our society—death, for example. Then they inevitably ask me what ‘hope’ means to Christians. I believe that Bach has already converted tens of thousands of Japanese to the Christian faith.

As an example of Bach's ability to make his listeners to Christians, Matzuki mentions a Japanese organist who told him that: ”Bach introduced me to God, Jesus, and Christianity. When I play a fugue, I can hear Bach talking to God.”

Obviously there is a connection between religiosity and music. Pythagoras (570-495 BC) considered music to be a reverberation of universal perfection. Since a tone results from the vibrations a string, the same kind of harmony between sound and motion probably prevails throughout the universe. In his attempt to clarify such a relationship, Pythagoras used mathematics. Through music we may get an idea of what Pythagoras called "the harmony of the spheres". For Pythagoras, music was unmistakably "God's voice."

Several major composers have been deeply religious, while others have complained that they were unable to feel the presence of the divine. For example Shostakovitj answered the question whether he was religious with a lamentation: " No, and I am very sorry about it.”

After writing about the balm to the soul that music may provide, let me now return to the monster, which during troublesome nights lurks under our beds – The Stress. Since stress affects our psyche, it may be appropriate to turn to the author, I hesitate to call him "scientist", who usually is associated with explanations about the state of the soul among modern human beings, namely Sigmund Freud. Obviously, the prophet of psychoanalysis did not have an ear for music. He could be profoundly moved by literature and art, in the latter case more by sculpture than painting, though he seemed to be a complete stranger to musical experiences.

Obviously, Freud never listened to music for pleasure, and he rarely wrote about music. One of Sigmund Freud's brother-in-laws, Harry Freud, claimed that his uncle "despised music", something that may seem strange, not the least considering the fact that he lived in the intensely musical Vienna. One of the few occasions when Freud mentioned music was in an article he wrote about Michelangelo's statue of Moses, which he in 1914 published anonymously in the magazine Imago. Freud began his analysis of the Moses Statue by declaring that he was far from being an art connoisseur, explaining that he was more interested in the content of art than its means of expression:

Nevertheless, works of art do exercise a powerful effect on me, especially those of literature and sculpture, less often painting. This has occasioned me, when I have been contemplating such things, to spend a long time before them trying to apprehend them in my own way, i.e. to explain to myself what their effect is due to. Wherever I cannot do it as for instance with music, I am almost incapable of obtaining any pleasure. Some rationalistic, or perhaps analytic, turn of mind in me rebels against being moved by a thing without knowing why I am thus affected and what it is that affects me.

.jpg)

It appears almost as if Freud was afraid of music; maybe due to the fact that it so difficult to describe in a meaningful manner, how it speaks directly to our inner feelings and thus repudiates any attempt at explanation - or with another word being "analysed". On the other hand, Freud´s friend, Romain Rolland, was extremely musical. Rolland, author, essayist, art historian and mystic, received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1915, with the motivation that it was awarded him:

as a tribute to the lofty idealism of his literary production and to the sympathy and love of truth with which he has described different types of human beings.

Rolland presided over the Department of Music History at the University of Sorbonne (he later left this position to become a full-time writer) and his great musicality and enthusiasm for the emotional power of music runs like a red thread through his life and activities. Rolland had an unwavering belief in humanity's ability for goodness and positively change of our living conditions. He was strongly influenced by Hindu philosophy and corresponded with Rabrindranath Tagore and Gandhi. In 1923, Rolland also launched an intensive correspondence with Freud. He tried to convince his pen pal about the meaning of what he called the "oceanic feeling":

The true Vedantic spirit does not start out with a system of preconceived ideas. It possesses absolute liberty and unrivalled courage among religions with regard to the facts to be observed and the diverse hypotheses it has laid down for their coordination. Never having been hampered by a priestly order, each man has been entirely free to search wherever he pleased for the spiritual explanation of the spectacle of the universe.

Vedanta is by Rolland apparently most akin to Adi Shankara´s (788-820 AD), advaita (non-dualistic) view that all opposites are mere illusions, the only absolutely certain and persistent fact of life is the vital force inherent in all existence – the Brahman, the soul of the Universe, the divine reality of all existence. Brahman is obviously identical with what Rolland calls the oceanic feeling, which he believed could be found among other things in music and true friendship.

In one of his letters to Rolland, Freud apologized for being insensitive to Rolland´s oceanic feeling, explaining that he was inaccessible to both mysticism and music. However, this standpoint did not prevent Freud from taking Rolland's perceptions as a starting point for his book Civilization and Its Discontents from 1929. His atheism blocked Freud from Rolland's notion of the presence of a religious sense of eternity and boundlessness as the true basis for a universal human community. Freud referred to his "scientific obsession” and declared that Rolland's belief was merely a fragmentary remnant of a childish consciousness, emerging from the fact that a child cannot distinguish her/his own existence from people and things surrounding her/him.

When the child is becoming more mature, it comes across increasingly negative aspects of the reality that it is surrounded by and in order to protect its own well-being, the child begins to build strategies in order to deal with a threatening reality. According to Freud, we constantly try to master a painful realisation of the certainty of our own death, nature´s cruelty and destructiveness and the fact that we are forced to share our lives with other people, who tend to make sure we comply with the laws of society.

A paradox is that we humans have created culture and civilization to protect us from the indifferent cruelty of nature, but at the same time we have invented a kind of community that plagues us as well. We have been transformed into neurotic beings through our adaption to cultural notions of a society that is supressing our natural urges. Progress in science and technology may have contributed to making our existence easier and happier, but since civilization has distanced us from our true nature, it has also been instrumental in making us distressed and unhappy. Not meeting all demands and continuously trying to control our needs and passions have made us frustrated.

The idea that Western civilization can be detrimental to our well-being prompted several “intellectuals” to welcome the First World War as an effective cure for thoughtless convenience and intellectual deprivation. To re-establish harmony between itself and nature, humanity was in dire need of a thorough "fire baptism". However, when young men returned from the hell of the trenches, mentally and physically injured by their gruesome experiences, they were far from being any "reborn" heroes that the pro-war propaganda had promised them to become. To cure the war veterans from anxiety, hopelessness and despair, scientists gave an ever increasing attention to how frustrating experiences affect body and mind.

Research did not only focus on the brain and the nervous system, but also on what has been labelled as the endocrine system. All mammals, birds and fish are endowed with various internal organs that discharge chemical substances, hormones, which circulate in the bloodstream throughout the body, carrying signals that initiate and coordinate different body functions. Hormones are produced in a variety of glands, such as the pituitary gland, the pancreas, ovaries, testicles, the thyroid gland, and adrenal glands. Unlike the nervous system, the endocrine system is not immediately effective, but it works for a long time and its effects are considerably longer. By producing and delivering different hormones, the brain's pituitary gland, or as is also called hypothalamus, carries all the necessary information to the endocrine system.

Knowledge of the endocrine system is relatively new. It was the English doctors Ernest Starling and William Bayliss who in 1905 realized that the fluid and mucus produced by different glands were produced without the support of the nervous system and thus gave rise to the medical discipline that was called endocrinology. Starling and Bayliss found the molecules produced by glands and acting as the body's signalling substances and named them hormones, from the ancient Greek name for “particles”. Different hormones initiate specific physiological and behavioural processes. Digestion, metabolism, breathing, tissue functions, sensory perceptions, sleep, breastfeeding, stress, growth, reproduction and mood are all dependent on hormone signals. Since hormones are palpable substances the pharmaceutical industry was, and still is, very interested in hormonal research and generously supported it at several universities.

János Hugo Bruno “Hans” Selye was one of many bright men who after being born around the fin-de-siècle in one or another city of the Austrian-Hungarian empire turned up in quite other places from where they spread amazing insights that forever have changed our lives.

Selye grew up in a Hungarian-speaking family in Komárom, a town spanning two facing banks of the Danube. When the border between Czechoslovakia and Hungary was established in 1920 Komárom came to be divided between two different nations. Selye´s family moved to Budapest, while Hans studied medicine at the Institute for General and Experimental Pathology in Prague, where he eventually became Doctor of both Medicine and Chemistry. In 1931, he received a visiting professorship in the United States and a few years later he continued his research in Montreal. When it darkened in Europe, he chose to stay in Canada. His Austrian mother was killed during the Hungarian Uprising in 1956 by a stray bullet. Selye had then long been active in the lucrative pursuit of new hormones.

To find hormones, experimental animals were injected with different substances to study whether they triggered chemical processes that could be used to track the body's hormone production. Already Starling and Bayliss had been subjected to violent criticism after they, in front of sixty students, had vivisected a brown terrier. Swedish women students reported the incident and animal lovers throughout Europe became extremely upset. In 1906, a statue in memory of The Brown Dog, plagued and killed by Starling and Bayliss was erected in London, and thousands of students, suffrages and union members marched through London with images and small sculptures depicting the dog. The protest resulted in a bloody confrontation with 400 police officers. Selye's research was also based on animal experiments and financed by government agencies, charities and pharmaceutical companies. After 1945 his institute at the University of Montreal employed 40 assistants who worked with 15,000 experimental animals. What was the main reason for this intensive activity?

Initially, Selye had among his laboratory rats found symptoms similar to those he had been confronted with as a young general practitioner in Prague where several of his patients had complained about more or less diffuse pains, in particular in joints and arms. They stated they had lost appetite and often had bouts of fever, while Selye could establish that several of them had enlarged spleen and/or liver, combined with "more general" symptoms. Since then, Selye had wondered why so many physicians had devoted so much thought and energy to curing "isolated" disease states, while so few of them had paid any attention to the state of "being just sick".

Selye did not find any new hormone, though he continued to inject his rats with a variety of concoctions, extracted from placenta, kidneys, spleen and a host of other organs, with consistently had the same results. Finally he injected toxic substances, like formalin, and the result turned out to be the same. Obviously, each time the body was exposed to the influence of a foreign matter, the brain´s pituitary gland transmitted similar signals to the endocrine system. Selye assumed that his rats did not only respond to the hormone injections, but also to stress caused by the laboratory environment and the disagreeable experiments. He concluded that the disease symptoms resulted from both physical and psychological influences.

In an article published in 1936 in the English journal Nature, A Syndrome Produced by Various Nocuous Agents, Selye introduced the term stress to describe the disease symptoms he had introduced among his experimental animals. According to Selye, stress could appear in two varieties; it could be a general adaptation syndrome meaning that the body has difficulties in adapting its functions to a specific external threat, or it could also be the development of a pathological condition, which origin it is difficult to track. According to Selye's article, stress or general adaptation syndrome develops in three phases - an initial alarm phase, followed by a stage of resistance, or adaptation, ultimately leading to an end stage of severe fatigue, or worse - death. Stress could develop from chronic diseases such as hypertension, stomach ulcers, kidney disease, diabetes, arthritis, asthma and cancer, but also severe cold, surgical damage, excessive emotional responses or excessive doses of drugs.

Selye had a tendency to refer most his notions to his own research findings, but there is no doubt about the fact that he was influenced by the spirit of the time and not the least Freud's theories about our "dissatisfaction in culture". After the First World War, neurasthenia, or as it nowadays generally is labelled chronic fatigue syndrome, was a very common diagnosis of nerve problems. It was even argued that neurasthenia was especially common among Jews because they had a "specific emotional character", or businessmen since they worried about the state of the stock exchange. Like stress, neurasthenia was a very broad term that included insomnia, anxiety, fatigue and difficulties in accepting responsibility. Selye's fame is mainly based on his linkage of the body´s chemical processes to "deficiencies in the body's defence - and adaptation mechanisms".

Selye was a hyperactive person, his average working day consisted of 10 to 14 hours, including weekends and holidays. He usually rose at five o'clock in the morning, took a dip in the cold water pool of his house's basement and then cycling the ten kilometres road to his laboratory.

He published 1700 research reports and 39 books. Together with the at the time very popular futurologist Alvin Toffler, Selye founded in 1975 the The American Institute of Stress to publicize and further develop his theories. Among other things, the Institute published a "stress test" consisting of 31 symptoms that every person should be aware of to avoid stress. Among some often very general signs of acute stress may be mentioned loud laugh, liquid anxiety, i.e. being worried and afraid without knowing the cause, dry mouth, an unnatural urge to urinate, increased smoking, and "an overwhelming desire to run and hide".

By the mid-1970s, stress management had developed into billion dollar industry. Academic research institutes were created, searching for cures for stress-related diseases, not to mention all the psychopharmacology that has developed around the phenomenon, as well as a wealth of books, specialist bookshops and various companies dedicated to stress management, relaxation theories, yoga and meditation.

Selye was largely integrated in that development. The point of increased smoking in his stress test is interesting, not the least due to the fact that Selye claimed that smoking was not particularly harmful, it could even be recommended as having a calming effect on nervous stress. The pipe smoking Selye often appeared in television shows, movies and advertisements where he questioned the link between smoking and cancer, pointing to stress as a far more serious threat to public health. It was Selye who, in search of funding for his stress research institute, had approached the tobacco industry. Only in 1969, Selye received $ 300,000 in financial support from the tobacco industry. For example, between 1970 and 1973, Philip Morris gave $ 50,000 a year to Selye for what was simply referred to as a "special project". Selye's defence of smoking appeared to be in line with Freud's argument that we should, for the sake of easing our anxiety, seek out viable ways to alleviate the pressure that modern society exposes us to:

The question is not “to smoke or not to smoke,” but to smoke or drink, eat, drive a car—or simply fret. Since we cannot discard our surplus energy, we must occupy it somehow … that often more damage is done by creating, through well-meant crusades of enlightenment, innumerable hypochondriacs whose main sickness is really the fear of sickness.

In addition to financial support from the tobacco industry, Selye also received support from other somewhat suspicious institutions, at least when it comes to public health. He obtained, as an example, significant contributions from the Sugar Research Foundation and consequently recommended a diet rich in carbohydrates as a viable antidote to stress.

Selye was nominated for the Nobel Prize not less than seventeen times, but he never received it. A contributing factor for denying him the prize may have been his unfortunate aptitude for self-centred propaganda. Most crucial was that what he believed and suggested were not always entirely correct. There was a lot of stress-inducing factors that he chose to ignore in his selective research. Nowadays, the estimation of Selye's contribution seems to be based mainly on the fact that his discoveries inspired others to make new breakthroughs and present better theories.

Famine, war and disease all remain with us, though the world is changing rapidly. I remember how I in the nineties first heard about cell phones; clumsy devices with antenna and the net, which was reached through the installation of a modem and basically worked like the phones of those days, with complicated subscription arrangements and fees based on usage per minute. After ten years all that has changed and an entirely new cyber world is now controlling our existence. Artificial intelligence is already about to create a new human species, Homo Sapiens will soon be replaced by another species whose brain and body are linked and dominated by devices and substances that we no longer are in entire control of. World famine decreases, epidemics are not as serious threats as before and although it may not seem to be so, armed conflicts are decreasing. After thousands of years of struggling to get food for the day and keep ourselves healthy, many of us are now confronted with entirely different problems.

Inventions and scientific advances develop with breath taking speed, while the results are not always what could be expected. Medical research claims all its efforts are dedicated to fight disease, but the results can have completely different consequences. After the First World War, plastic surgery was advanced to reconstruct the horrendously deformed faces of injured soldiers, but the technology soon became a billion dollar industry to "improve" the appearance of those who can afford to pay for it. Viagra was originally a cardiac medicine, but it is now used to increase male potency. For the good or bad, our lives and our thinking are constantly adapted to scientific advances.

Not the least has Hans Selyes's research contributed to the brave new world we now live in. The discovery that a variety of chemical concoctions can affect our mood, thinking and behaviour and our innermost feelings, has made that the drug industry from the beginning of the fifties has filled the market with a variety of miraculous drugs - chlorpromazine to cure psychoses, lithium carbonate to cure obsessions, tricyclic drugs and monoamine oxidase inhibitors to cure depression, benzodiazepine to cure sleep disorders, etc. etc.

Why suffer from stress and anxiety? Forget economic growth, social reforms and political revolutions. Humanity can become better-off through easier means. Why just not manipulate human biochemistry? During 2011, 2.5 million children in the US were treated with chemical concoctions, mainly methylphenidate, to relieve attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), or simply hyperactivity. Not only to alleviate acute concentration difficulties, but also to meet teachers 'and parents' learning requirements for their young. There are drugs for dealing with all kinds of mental barriers - soldiers are provided with drugs to become brave and ruthless, athletes to become stronger and more efficient and schoolchildren to become smarter and more ambitious. I recently read an exciting and thoughtful book about the artificial future that soon will change our lives - Yuval Harari´s Homo Deus.

Everything changes. In twenty years from now the present will be incomprehensibly outdated. Nevertheless, despite this bold new cyber world, I sincerely hope that nature remains to console our children and grandchildren. That they, like you and I, may lay down among the green fragrance of grass, close their eyes, let the sun warm their faces and listen to a blackbird's song. Or cuddle a sleeping infant in their loving embrace.

Tense nerves, stress hormones being released in the blood stream, tingling anxiety, the body being relentlessly worn down – all these are bleak elements of our human existence. However, do not allow the beauty of life be ignored. Also remember Havamal's wise word that a human is human´s happiness. Especially in those times when a generalizing idiocy strives to turn everyone and everything into threat and misery. And then we have the music! Listen to Beethoven's Ninth:

Oh friends, not these sounds!

Let us instead strike up more pleasing

and more joyful ones!

Joy!

Joy!

Joy, beautiful spark of divinity,

Daughter from Elysium,

We enter, burning with fervour,

heavenly being, your sanctuary!

Beckett, Samuel (2009) Company/ Ill Seen Ill Said/ Worstward Ho/ Stirrings Still. London: Faber & Faber. Burkert, Walter (1972) Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Cambridge Ma: Harvard University Press. Cantor, David and Edmund Ramsden (2014) Stress, Shock and Adaption in the Twentieth Century. Rochester NY: University of Rochester Press. Fischer, David James (2003) Romain Rolland and the Politics of Intellectual Engagement. London and New York: Routledge. Freud, Sigmund (2002) Civilization and its Discontents. London: Penguin Modern Classics. “The Moses of Michelangelo” in Gay, Peter (ed.) The Freud Reader. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. Gammond, Peter (1982) Schubert. London: Methuen. Larrington, Caroline (2014) The Poetic Edda. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Nietzsche, Friedrich (1990) The Twilight of the Idols and the Anti-Christ: or How to Philosophize with a Hammer. London: Penguin Classics. Pasternak, Boris (1973) The Last Summer. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Modern Classics. Petticrew, Marc and Kelley Lee (2011) “The Father of Stress” Meets “Big Tobacco”: Hans Selye and the Tobacco Industry”, in American Journal of Public Health, March. Schubert, Franz (1828) Doppelgänger https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fKVnL9JvuO8 Selye, Hans (1977) The Stress of My Life: A scientist´s memoirs. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. Schleef, Caroline (1943) Charcoal Burner's Ballad and Other Poems by Dan Andersson. New York: Fine Editions Press. Thomson, Damian (2016) “Does the great Bach conductor Masaaki Suzuki think his audience will burn in hell?” in The Spectator, 12 March. Volkov, Solomon (1984) Testimony: The memoirs of Dimitri Shostakovich. New York: Limelight Editions.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)