WHEN POLAND SAVED EUROPE: Nationalism, Communism and Jews

Recently I flew to my oldest daughter's Masters Graduation at Prague Theatre Academy (DAMU) and then made a stopover in Warsaw. It was the first time I was there for more than ten years. At the end of the last century and at the beginning of this one, I worked in Stockholm, while the family was living in Rome. At that time, there were no low cost airlines and I used to fly to Rome with LOT and thus had to make a more than half a day stopover in Warsaw, which was enough time for a nice dinner in the Old Town or a visit to the National Museum, which in those days was a run-down place and so was the airport, but there was a an excellent bookshop well stocked with Polish movies with English subtitles, as well as quite a lot of literature translated into English and German, all complemented by a friendly lady who knew English and happily and lively could recommend CDs, books and movies. I did not miss any opportunity to look into her shop and come out with a book, a CD or a movie, always interesting stuff.

Now everything had changed. I did not have time go into town and the airport was completely modernized. The cozy bookstore had disappeared and W H Smith'sinternational book emporium did not sell any Polish books translated into an understandable language. No one could recommend any nice CDs, and there were no Polish DVDs. Since I had a few hours to kill and needed something to read, I bought the only book about Polish history that I could find in English: Warsaw 1920: Lenin´s failed conquest of Europe by Adam Zamosky.

Apparently, the Poles had no less than two times "saved" Europe in the sense that Polish troops prevented serious attempts at conquest from the East (not counting the battle of Legnica in 1241 when a huge Mongol invasion was avoided). If they had not done so the times we now live in would probably have been completely different. The first time the Poles managed to stem the onslaught of a mighty army from the East I had by chance read about only two weeks before I ended up at the Chopin airport in Warsaw. Then I had on a flight from Rome to Copenhagen plowed through a comic book by the Italian master cartoonist Sergio Toppi, who narrated how Jan Sobieski with his men-at-arms in 1683 had arrived just in time to save the Austrian Emperor from a crushing defeat.

Vienna was beleaguered by a 200,000-strong army commanded by the Albanian Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa. It was the Turkish Sultan Mehmed IV who had decided to bet everything on one card and with his elite troops, along with a motley crew of professional warriors from all over the Ottoman Empire, once and for all crush the Hapsburg Empire and subject Europe to The True Faith.

The occasion was well chosen. The Catholic Emperor Leopold the First was threatened by his cousin Louis XIV in the west, by Protestant armies in the north, a variety of rebels within his own empire, and as told above - by the Ottomans in the east. During the several-month long siege the Emperor sent desperate pleas for help to his Catholic fellow-believers. Finally there appeared a 70,000-strong Polish-German army, led by the Polish King Jan III Sobieski.

After a day of bloody infantry and artillery fighting against superior Turkish forces Jan Sobieski initiated the hitherto largest cavalry charge in the history of Europe. 20,000 riders rushed forward towards the Ottoman forces. They were headed by 3,000 winged Polish hussars; they had eagle feathers attached to their armor. Like a mighty wedge they crashed into the Turkish Janissaries, closely followed by the entire cavalry army. The resistance was broken, the siege was immediately lifted and the Sultan's warriors scattered in panic.

More than two centuries later the hitherto successful history of cavalry shocks ended. This time it was the Poles who distinguished themselves once more. The sparse forests and fields outside the village of Komarów in Galicia, in southeastern Poland was at the end of August 1920 the scene of the largest cavalry battle since the Napoleonic Wars. 1, 700 Polish hussars attacked 17, 500 mounted Russians. The battle ended in disaster for The First Russian Cavalry Army, or as it is also was called – The Red Cavalry. Semyon Budyonny's Cossacks become encircled by the Poles, something which mainly was due to the fact that Budjonnyjs ´senior officer, Aleksandr Yegerov, had been badly advised by his political commissar, Joseph Stalin, and did not follow orders coming from the Soviet Commander in Chief.

The result was that after the main Russian army had been thoroughly defeated just outside Warsaw the southern invasion army collapsed as well. Demoralized hordes of Cossacks pulled, plundering and murdering, back to Russia. Thus Lenin's dream of spreading communism came to nothing. The dream was not unreasonable. Germany had surrendered and its troops were about to leave Eastern Europe. A variety of ethnic groups within the remains of the Habsburg and Russian empires tried to organize themselves as nations. People were worn down and tired of war; they lacked sufficient arms and armies, but were nevertheless full of enthusiasm at the prospect of becoming citizens of independent nation states.

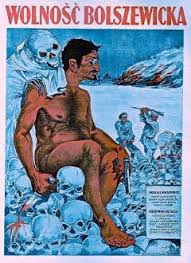

The Western European victors could not engage in any defense of the new nations and in this void Bolsheviks were able pounce on their western neighboring states at full strength. Lenin believed in success and confided to Stalin: "I think we should promote a revolution in Italy. In my opinion, we should sovietize Hungary and perhaps even the Czech Republic and Romania." The failed revolutions in Bavaria, Berlin and the recently defeated Hungarian Soviet Republic, as well as interrupted uprisings in Austria and Northern Italy threatened to paralyze the spread of world socialism. Lenin's plan was to inspire a new wave of violent revolutions. The Red Army would occupy Poland and Germany, as well as promoting revolutions in Hungary, the Czech Republic and Romania.

Lenin's plans were in line with Lev Trotsky's idea that the revolution had to be carried forward ”on the points of bayonets [...] through Kiev leads the straight route for uniting with Austro-Hungarian revolution, just as through Pskov and Vilnius goes the way for uniting with German revolution. Offensive on all fronts! Offensive on the west front, offensive on the south front, offensive on the all revolutionary fronts!"

The twenty-seven-years old, military genius Mikhail Tukhachevsky is credited with the theory of deep operations, meaning that combined heavily armed formations strike deep behind enemy lines to destroy their rear and logistics. Tukhachevsky was able to make his troops smash through the Polish defenses and quickly make their way to Warsaw's suburbs.

When I was in school, it was common to emphasize that the fate of the world depended on socio-economic factors. The influence of outstanding personalities was not decisive. Leaders were created by the specific social conditions of their times. I have often doubted such reasoning. What would the world become without Hitler, Stalin or Mao? Were these power-hungry maniacs nothing more than the result of socio-economic conditions? Could Poland have beaten back the Russian attack without Józef Piłsudski? Had I really believed in theories of the socio-economic forces´ supreme power, I had not committed myself to the reading of biographies of Stalin, Hitler and Mao.

Like so many other significant Poles, writers and statesmen, Pilsudski was born in Lithuania by fiercely patriotic, Polish aristocrats. His opposition to the Russian Empire resulted in his expulsion from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Vilna, he was arrested and spent five years in Siberian captivity. During the First World War he fought against the Russians within the ranks of the armies of Germany and Austria-Hungary. When he refused to swear an oath of allegiance to the Germans he was imprisoned, but was released when they surrendered and the First World War ended and he was then elected as the free Poland's first regent. From the beginning of his political career, Pilsudski had been a Social Democrat, but while in power he formed a coalition government that quickly implemented a series of reforms, such as free and compulsory education, eight-hour workday and women's suffrage.

Pilsudski was a headstrong and principled man. As a military commander he had been revered by his subordinates and was known to act only after having been thoroughly informed, but then he had made a decision he rarely hesitated. He was a man of resilient habits and rarely broke his routines, unless the situation demanded it. His took his meals in a simple, inexpensive restaurant, living in a Spartan manner, working hard until late into the night. He was a direct man, endowed with a harsh humor. Once in power Pilsudski abandoned the socialist camp, disliked being called "comrade" and declared: "Comrades, I took the red tram of Socialism to the stop called Independence, and that's where I got off. You may keep on to the final stop if you wish, but from now on let's address each other as ´Mister´.”

Pilsudski was a grim warrior, who had spent many years in the field. Often grumpy, always completely fearless, he supported social justice and opposed the political forces that claimed there was a Polish national specificity, thus he could not be regarded as decidedly conservative, though he was hardly a pacifist, but claimed that: "Only the sword now carries any weight in the balance for the destiny of a nation."

When the superior Russian army approached Warsaw, Pilsudski listened attentively to various advisors, but then decided on his own that the nation had to follow a bold plan of his own design. He divided his troops between various sectors of the Capital and organized a citizens´ militia in support of its defense and then headed south to bring up army units, which had been placed in Galicia to prevent Russian armies from invading the country from Ukraine. Against all odds Warsaw´s defenders were able to ward off the Russian onslaught until Piłsudski´s army attacked them from the rear. The bewildered Russians fled to the north, where they surrendered to the German army in East Prussia, or ended up on the other side of the Russian border, closely pursued by the triumphant Poles.

Both armies were well aware that a ceasefire had to be negotiated as soon as possible. The Poles recognized the danger of getting too far into Russian territory and the Russians could not endure that their troops continued to be slaughtered while they were thinning out due to mass desertions. The Poles had to, as quickly as possible, regain all their lost ground, while the Russians had to put an end to the mass flight and stem the onslaught of enemies. A desperate Lenin ordered the Commander of the Armed Forces, Sergey Kamenev, to fight back the Polish at all cost, meaning that doing so he did not have to respect the escalating human losses. Reserve troops poured into to the ever-receding front. Kamenev complained that most of the men were not sufficiently armed and that several of the newly arrived soldiers even lacked uniforms. Lenin replied: "I don´t care if they fight in their underwear, but fight they must!"

Pilsudski had not only the same drooping mustache and grim appearance as his hero Jan Sobieski, like him he also halted a major foreign invasion attempt directed against a weakened and confused Europe. It had actually looked as if Lenin's desire for a socialist Europe was about to be realized. However, against all odds, Poland had defeated Russia and it was not until Stalin signed his infamous pact with Hitler that Russia again could extend its borders towards the West.

When I fly back from Prague and looked down at the largely unbroken plains covering Poland, south of the Baltic Sea and north of the Carpathians I understood why armies for centuries had marched back and forth across that fertile stretch of land, watering it with blood and causing immense suffering.

Only during World War II, 5 to 6 million, of whom over 3 million of Jewish origin, were forced into the concentration camps where they were murdered at an amazing scale and speed. 2.8 million Poles were transferred to slave labor camps in Germany. The goal of the Nazi occupation of Poland had been to annihilate Polish civilization, to transform the Poles to an illiterate workforce and exterminate the entire Polish intelligentsia.

On the Soviet side of occupied Poland, captured Polish soldiers were executed en masse, of those 4,500 officers were massacred in the Katyn forest in western Russia. An estimated 20.000 to 30.000 Polish prisoners were liquidated by the NKVD (People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs, i.e. the Soviet Security), while between one and one and a half million inhabitants in the Soviet annexed provinces, mainly Poles and Jews, but also Ukrainians and Byelorussians, were deported to the Soviet interior. Of those 350,000 died through starvation and hardship. Approximately half a million Poles were imprisoned and sent to the Gulag. Meanwhile, Poles fought in all theatres of war; in Europe, North Africa and at the Atlantic Ocean. By the end of the war, 250,000 Poles were fighting on the Western Front, while nearly 400,000 followed the Soviet army and attacked Berlin.

As I mentioned in a previous blog post, while I was living in Paris I visited on several occasions the battlefields of Verdun where I experienced the eerie atmosphere that after a hundred years still looms over a place where hundreds of thousands young men needlessly were slaughtered. The hellish trench warfare on the Western Front is well known through a vast amount of masterful depictions from those who survived the muddy hell with its incessant bombardment, rotting corpses, lice and ravenous rats. The eastern front is not so well known, even if the suffering there was as awful as in the west. Furthermore, the war lasted longer there and the civilians were extremely hard hit.

Galicia, where the atrocious battle between Budyonny's Cossacks and Polish lancers took place, was an equally massive slaughter place as the muddy killing fields of Flanders and Lorraine. At almost exactly the same spot as the battle in 1920 took place in 1914 had an Austro-Hungarian army in 1914 halted a Russian invasion force of 200 000 men and taken 20,000 Russians as prisoners.

Two years later, Galicia was again attacked, this time by Russia's Southern Army Group, under command of General Aleksei Brusilov. After fierce fighting they pushed back the Austro-Hungarian forces. Russian losses amounted to 1.4 million men and the Central Powers lost 800 000, this makes the Brusilov Offensive one of the bloodiest battles in both World War I and the entire history of humankind.

It was in Galicia the the author of The Good Soldier Švejk, Jaroslav Hašek, surrendered to the Russians, became a prisoner of war and later Soviet Commissar, before he joined the Czech legionaries who had been trapped in the Soviet Union and which fate I wrote about in in an earlier blog post about Shanghai jazz.

When you read books from the Eastern Front, it is striking how volatile it was if compared to the Western Front, lacking the seemingly endless suffering of being buried in flooded trenches under constant shelling. The Eastern armies often moved over large areas. Švejk´s adventure, for example, takes place under constant train movements back and forth until he finally ends up at the front lines in Galicia, which also fluctuated continuously.

Death came suddenly and violently in the form of vast battles in open fields or sudden attacks on small, often isolated, troop units. Isaac Babel's remarkable novelRed Cavalry is based on his experiences gained from riding with warring Cossacks. The language is simple and written in a style that makes me believe that Hemingway must have known about Babel´s prose and learned from it. It appears as if Babel has been able reproduce the rhythm of the trotting horses while his Cossack mates constantly move from one miserable and plundered Galician village to another.

The fighting was merciless. Polish troops routinely executed captured Soviet commissars, while Soviet troops in their turn shot any Polish officer they captured and cut the throat of priests, landlords and wealthy landowners. Both sides murdered Jews. The atmosphere was ripe for atrocities. Soldiers often moved in small units, engulfed in mistrust, confusion and general insecurity. They ended up in deep forests, or far out on treacherous marsh lands and camped among terrified and starving villagers, whose language, customs, loyalties and fears they did not understand. A surprise attack could come at any time, from every conceivable direction. Individual units could find that the front line had moved either forward or backward, unexpectedly leaving them stranded in hostile, enemy territory. Nervous misconceptions could lead to bloodshed and revenge tended to be cruel and unforgiving.

Those who fared especially bad were the Jews. Galicia was part of the Russian Jewish settlement area, called the Pale of Settlement, after the Russian word for “pole”, i.e. stake/frontier. During the Middle Ages, when Jews were persecuted by fanatical crusaders, accused of the Black Death and was expelled from several countries, they were given refuge in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. When Poland-Lithuania was divided up by the end of the 18th century a large portion of the Jewish population ended up under Russian rule and in 1835 Tsar Nicholas I, with his fear of revolutionaries and "internal enemies", decided that Jews should not be allowed to live outside the Pale, which consisted of a broad "corridor" stretching from Latvia in the north to the Ukraine in the south.

Since Jews generally were forbidden to own land many of them ended up in cities and villages, where they worked as merchants, artisans, tailors or in "intellectual" professions such as doctors, lawyers and dentists. Since it was their religion that throughout the centuries had characterized their life style and separated them from their Christian neighbors many Jews who identified themselves as such were strictly religious and the Pale became a vibrant center for Jewish theology. Many Jews adhered to faiths and sects that decreed a special way of life and a distinctive attire.

In The Fateful Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk During the World War haggling Jews occasionally turn up, equipped with kaftans and screw curls they sell illicit liquor and engage in all manner of bargaining and petty crimes. Although soldiers and officers who ended up in Galicia, which for several of them was a strange and foreign part of Europe, were generally not particularly anti-Semitic, however they had, like many Europeans, a deeply ingrained view of Jews as smart and backslapping businessmen. A prejudice that included the poor, desperate shtetlinhabitants, who for decades had been subjected to merciless pogroms. Typical is the attitude of the Hungarian artist Béla Zombory-Moldovan, who left behind an unusually well-written diary about his time as an officer at the Galician front. After being seriously wounded he was on a cart transported away from the front line. His wagon trail made a stop in a shtetl where the population repeatedly had been plundered and abused by passing troop units from both the Russian and the Austro-Hungarian army.

We had entered a poverty-stricken village of a few mean little houses. The streets were deserted; the inhabitants had retreated indoors, out of sight, from where they stole the occasional curious glance in our direction. One solitary Jew, wearing a kaftan, had summoned up the courage to stand at the roadside, holding out a wine glass filled with a yellowish liquid. I took it to be lemonade. I beckoned to him. Eagerly he ran up to the cart.

“Limonade?”

“Ja, ja sehr fein.”

He reached it out to me with a skinny hand. I took it gratefully and, without much analysis of the fluid´s composition, gulped it down in one go. It felt good. Whatever it was, it was liquid. “Ich danke,” I said, handing back the glass. He stared at me with an expression of surprise and disappointment. Suddenly it dawned upon me: his motivation wasn´t compassion towards the wounded. He wanted paying. Rage filled me. Damned bloodsucker! He has the gall to screw money out of a poor wounded soldier who has escaped death by a hair and lost everything he had. I shouted at him: Off with you! I have nothing!”He jumped back in mortal fear and ran off, side-locks flapping madly, to one of the little huts. I had to smile: hear was someone I could scare, even in my sorry state. I had no idea I could still have such an effect.

The fear of impoverished Jews was understandable, to say the least. During the First World War, battles raged back and forth across the Pale and it did not get any better after the peace treaty between Russians and Germans. The fighting continued and those who suffered the worst were Jews. Violent pogroms, often tolerated and sometimes even supported by the Tsar had taken place before the War and conditions for the Jews had worsened even further during the Civil War, especially Deniken´s “white” troops raged wildly among Jewish shtetls. Both Alexander III and Nicholas II embraced Orthodoxy, autocracy and nationalism, and were basically anti-Semites. Accordingly, similar views were prevalent among the Russian upper class and not least several of the leaders of the "White Army" regarded Jews as inferior beings. This way of thinking was not lacking from officers and men within the ranks of the Red Army, although it was led and organized by a Jew - Lev Trotsky. For example, was the great commander Tukhachevsky, who had been in charge of the initially successful attack on Poland, a fanatical anti-Semite. In a conversation with a French officer Tukhachevsky claimed:

The Jews brought us Christianity, and that is reason enough to loathe them […] And anyway, they belong to a low race. You cannot understand this, you Frenchmen for whom equality is a dogma. The Jew is a dog, son of a bitch, and he spread his fleas throughout the world. It is he who has done more than any other to inoculate us with the plague of civilization, and who would like to give us his morality of money, of capital, and the socialist doctrine is a branch of universal Christianity … I loathe all socialists, Christians and Jews.

Admittedly Tukhachevsky was in charge of a Bolshevik army, but among friends and acolytes he confessed: “Why should I care if it is with the Red Banner or the Orthodox Cross that I conquer Constantinople?”

The Jews were and remained strangers. Many young Jews considered socialism to be an escape from the shtetls´ narrow world and the Bolsheviks had furthermore in 1918 issued a decree condemning anti-Semitism, calling upon workers and peasants to fight it. Yet many Bolsheviks still considered Jews to be an ethnic group that it would be almost impossible to assimilate and thus a constant threat to Communism. In 1919 Lenin wrote a draft for a directive for the Communist Party called Policies on the Ukraine:

Jews and city dwellers in the Ukraine must be taken by hedgehog-skin gauntlets, sent to fight on front lines and should never be allowed to any administrative positions (except a negligible percentage, in exceptional cases, and under [our] class control).

The revolutionary unrest in Russia and Ukraine, as well as pogroms carried out by units from the white armies and hordes of Cossacks forced numerous Jews to flee across the border and into Poland. Between 1918 and 1921, there were more than 1,300 pogroms in the Ukraine alone, during which between 30,000 and 70,000 Jews were massacred. The pogroms were characterized by a mindless cruelty and recklessness. Thousands of women were raped, hundreds shtetls looted and razed. Over half the number of these atrocities were perpetrated by units attached to Petlura´s Ukrainian National Army, this in spite of the fact that the Ukrainian People´s Republic under Symon Petliura´s shortlived government had guarenteed Jews full equality and autonomy and included several Jewish ministers. Nevertheless, they were unable to contole their own army with its hard core of Cosacks known to nurture an age-old hatred of Jews. About twenty percent of the poromes were staged by Deniken´s White Russan army, which fought both the Ukrainians and the Bolsheviks.

In their propaganda, the Bolsheviks took advantage of these slaughters and mainly blamed the Poles for abusing the Jewish population. Isaac Babel wrote several incendiary newspaper articles about Polish assaults on Jewish shtetls:

In the village we encountered a Jewish population that had been looted of its money and health, cut down by sabers and seriously wounded. Our fighters, who had been through one thing after another and for whose swords many a head had rolled, recoiled in fear at the sight that met them. Among the miserable huts, smashed to the ground, were seventy years old people bathing in pools of blood from skulls crushed with axes. There were surviving young children with severed fingers. Raped old women with ripped bellies who had fallen down in the corners with faces solidified into a wild unbearable despair. Beside the dead, the living were crawling, jostling among dissected corpses, soaking their hands and faces in the messy, smelly blood too afraid to crawl out of their houses since they believed that all had not finished yet. [...] This is our response to the Polish Red Cross´ cries about Russian atrocities. The dogs that have ripped enough humans to pieces are now howling. The killers who were not satisfied by their slaughter are now creeping out of their graves. Whack them, members of the valiantly fighting equestrian army! We need to nail down the lid of their coffins, before they rise from their stinking graves!

In the diary that Babel kept during his time with Budyonny's troops, he is completely honest and admits that the Red Army Cossacks were equally cruel to the Jews as the Polish and Ukrainian soldiers, he states that it is "the same hatred, the same Cossacks, the same cruelty, different armies, what a nonsense. The life of the shtetl. There is no salvation!" During the retreat after their crushing defeat outside Komarów, Babel witnesses how furious hordes of Cossacks plunge into the small town, where they are beating up and killing Jews. They ride into the synagogue and throw away the sacred Torah scrolls from their gold-embroidered silk and velvet pouches, which they rip apart to use as saddle blankets.

In his novel, Babel is more resigned than in his newspaper articles and diary entries, but a hard pulse may be perceived behind the text. Being a Jew himself and fluent in both Yiddish and Hebrew Babel is painfully aware of the fact that his people are suffering persecution and violent abuse from all parties in the cruel conflict and even though he proudly confesses himself to be a stout Bolshevik, he has doubts about his own righteousness, something that may be felt all throughout the novel. When his narrator (Babel hides himself behind a fictitious figure) visits a heartbroken group of Hasidic rabbis during the Sabbath and late at night talks with them, his respect and reverence shine through the tough Bolshevik stance. He gives the word to an old antique dealer and Talmudic scholar:

“The Revolution,” mutters Gedali, “we will say yes to it … Yes, I cry the Revolution, but it hides its face from Gedali, and ahead send naught but shooting … Now, the Poles were shooting, kind sir, because they were Counter-Revolution. You shoot because you are the Revolution … But surely the Revolution means joy. The Revolution is the good deed of good men. But good men do not kill. Then how is Gedali to tell which the Revolution is and which is the Counter-Revolution?” Faced by this unresolvable dilemma Gedali opts for a strictly moral, meaning nonpolitical solution: “The International, we know what the International is … And I want an International of good men. I would like every soul to be listed and given first-category rations.

Another night the narrator finds himself in an abandoned barn, sharing a smoke with a Russian peasant, what the armed peasant entrusts him seems to be quite prophetic. Babel´s Red Cavalry was written in 1924:

“It’s all the fault of those Yids,” he said. “That’s how we see it, and that’s how the Poles see it. After the war there’ll be hardly any of them left. How many Yids you reckon there’s in the world?”

“Around ten million,” I answered, and began to bridle my horse.

“There’ll be two hundred thousand of them left!” the muzhik yelled, grabbing me by the arm, afraid that I was about to leave.

At least when it comes to Poland the peasant´s prediction was fairly accurate. Before the Second World War, 3.5 million Jews lived within what is now Poland's borders, in June 1946 there were approximately 220,000 left, the rest had been killed.

It happened that the Polish soldiers and militia slaughtered defenseless Jews, but the fact is that Polish authorities to a greater extent than Russians and Ukrainians punished the cruelties committed against its Jewish population. Partly due to the fact that United States considered Poland as a nascent ally to counter the influence of Soviet Russia and reports about atrocities committed against Jews could damage a future cooperation.

As a matter of fact, the Polish soldiers who distinguished themselves when it came to assaulting Jews were some units from the so-called Blue Army. It consisted of Poles who had served on the French side at the Western Front. Under the command of General Józef Haller they came to have a decisive influence on the Polish efforts during the Polish-Russian War. It turned out that most of those who committed atrocities against Jews were certain units from the 24 000 Polish-Americans who had enlisted in the Blue Army. Their behavior was blamed on their sense of vulnerability in an unfamiliar environment and their abhorrence of Communism. Already before the Polish-Russian war had conservative propaganda all over the world are equaled Eastern Jews with Communism and there was much talk about of what was called Judeo-Bolshevism as an integrated a part of an absurd “Jewish World Conspiracy” myth, which indicated that a secret, global Jewish community conspired to control the entire world.

Not all Galician Jews were deeply religious and satisfied with living in isolated, tiny and unworldly shtetls. There was a large group of young Jews who strove to break out from the shackles of what they called a "ghetto environment" and advance both intellectually and career-wise. It is not without reason that Galicia has produced no less than four Nobel Prize winners: Isidor Isaac Rabi and Georges Charpak in Physics, Roald Hofman in Chemistry and Shmul Agnon in Literature. Many young Jews found their way to Communism, which for them meant an entirely new form of assimilation - they did not have to convert to another religion, or turn into nationalists, instead they could feel as integrated members of a global movement for social justice; independent of race, religion and nationality.

It is a fact that several Jews joined the Bolshevik party, but of its 23 000 members just after the coup of 1917 only 364 were Jews, although several men in leading positions had a Jewish origin – particularly powerful were men like Grigory Zinoviev, Mosiei, Uristsky, Yakov Sverdlov, Grigory Sokolnikov and Lev Troskij. Other Bolsheviks were identified as Jews, even if they were Russians or from other ethnic groups. With the exception of Uritsky and Sverdlov, who died before 1920, the leaders mentioned above were all to be liquidated on Stalin's orders. During most of the 1920s less than six percent of the Soviet leadership and administration were of Jewish descent.

The majority of the Jewish communities of the Pale of Settlement were fervently religious and quite conservative. If young Jews found their way to Bolshevism it was often at the expense of cutting off their attachment to families and former co-religionists. The majority of the population of the shtetls worried about the Bolshevik´s atheism, their russification efforts and their constant preaching of class struggle. Many fled to the west, to Poland, Austria, the USA and even Australia and Argentina. In December 1920, the Jewish People's Assembly in Eastern Galicia voted for incorporation with the Polish nation.

After I was back in Sweden after my short, but delightful visit to Prague I was shocked by the news of 2nd December that the Sweden Democrats had voted against the Social Democrats' budget and that the Government accordingly had announced re-elections in March 2015. Shocked? Why being such an alarmist? Several friends laughed at my worries. What was the problem? Sweden Democrats represent no danger. They have no majority, are no Nazis (not anymore at least). It is a democratic party. After all – this is Sweden, a civilized country, with a long and solid democratic tradition.

Nevertheless, I am not at all reassured by such self-congratulatory platitudes and wonder if the Sweden Democrats would consider that I had misunderstood their party program if I claim that they emphasize the importance of preserving our national heritage and oppose a multicultural society. Their party wants to unite us Swedes around "The Church of Our Fathers" and strengthen its position within our society, by the way - the Church should be more aggressive and outspoken in its domestic mission, and not tolerate any propagation of foreign religions on Swedish soil. Immigration from "culturally distant countries" must be discouraged and the construction of places of worship of other religions besides Christianity must be offset, possibly with the exception of the Mosaic faith. Though I suspect that quite a lot of the Sweden Democrats' old fighters continue to harbor suspicions, questioning if the Jews really are assimilated in the meaning the SD endow the concept with, namely if Jews really perceive themselves as Swedes, speak fluent Swedish, live in accordance with the Swedish culture, consider Swedish history as their own and feel more loyalty to the Swedish nation than any other nation, and even if they fulfill all of these criteria the Jews are known to be smart and cunning and would be capable of fooling the gullible Swedes.

The party demands more space for teaching Swedish history in Swedish schools, which moreover do not have to be responsible for mother tongue teaching in languages other than Swedish. The Swedish cultural heritage has to gain more presence and visibility within the public sector. Immigrant associations and similar endeavors supporting foreign cultural influences should not receive any state or municipal support and funding.

I am a member of the Swedish Church, have studied theology, believe myself to be fairly proficient in Swedish history and am teaching Swedish, though the Sweden conjured up by the Sweden Democrats is definitely not the kind of Sweden I would like to live in. I am convinced that if the word "Sweden" during the thirties was replaced with "Poland", or why not "Germany" or "Latvia", then the Sweden Democrats´ party program would have fitted like a glove for the extreme national parties that during those turbulent times grew strong in these countries and later came to create an almost inconceivable misery. In Poland, "The Church of Our Fathers" would be synonymous with the official Catholicism, but otherwise everything would be fairly similar. "Culturally alien" elements would back then be the Jews and other minorities, many of whom had arrived as desperate refugees from repressive regimes in neighboring countries.

The failed Russian attack on Poland had fatal consequences for the Jews. When the American anarchist Emma Goldman visited Galicia in 1920 she was shocked by precarious situation the impoverished Jews, stating that although several Jews had joined the revolution, the majority suffered from persecution mainly due to the fact they were small traders and often deeply religious. Compatriots who were not Communists considered that the fact that Bolsheviks had granted more freedom for the Jews only served to increase the hatred against them. Through there forced requisitions, punitive expeditions and Tjeka terror brought the Bolsheviks reluctance of people in general and because many in Russia, Ukraine. Lithuania, Belarus and Poland suspect that the revolution favored the Jews escalated hatred and distrust. To avoid a common suspicion that they particularly benefitted the Jews the Bolsheviks tended to punish them harsher than the non-Jews. Yiddish and Hebrew were banned as teaching languages. Goldman noted that the Bolsheviks allowed the Jews to survive "physically", but culturally and spiritually they were sentencing them to death.

Although anti-Semitism was smoldering in Poland its excesses were curbed by the authorities. Perhaps this was in large part due to Józef Piłsudski´s power and influence. He pursued a policy based on what he called Miedzymore, meaning "between the seas". He wished for a strong federation between the Baltic States, Belarus and Ukraine. Hence, a band of independent states would extend between the Baltic and the Black Seas constituting a barrier against the Soviet Union´s expansive strivings. Such a protective area would largely to a large degree coincide with the Pale of Settlement and this could be one reason why Pilsudski was so sympathetic to the Jews.

Pilsudski assumed that Poland's survival as a state depended on an apprehension that all communities in Eastern Europe should cooperate and demonstrate their tolerance towards their minorities; otherwise would Soviet Union exploit their internal divisions and once again attack them. Until his death in 1935 Pilsudski fought against a conviction which in Poland was called Żydokomuna, Jewish Communism. A conception that found its origin in a pamphlet written already in 1817, but not published until 1858. its title was The year 3333, or the incredibledream and it predicted a future in which the Jews had become so numerous and powerful that they had taken over Poland, renaming Warsaw to Moszkopolis and oppressing the Catholics. Thus, a fear that does not seem to be so different from the horror scenario that several Sweden Democrats conjure up around what they call the islamization of Sweden.

A quite common perception of a surreptitious judaization of Poland was fiercely supported by the National Democratic Party, Endeks. What they considered to be Piłsudski´s dangerous, liberal attitudes towards Polish minorities were harshly opposed by Endeks and the increasingly authoritarian Piłsudski answered with an increased suppression of his political opponents. During the Great Depression of the early thirties Endeks initiated several violent anti-Semitic campaigns. They declared that the number of Jews residing in Poland ought to be drastically limited and a number of comprehensive boycotts were launched against Jewish shops and businesses. When Pilsudski died in 1935, Endeks made it clear that the "Jewish question" had to become an overriding political priority, stressing their opinion that not only did the Jews foster an unholy alliance between Communism and big business; they were also behind most of the serious crimes in the country.

Endeks´ propaganda convinced several municipalities to limit Jews' access to sports facilities and schools. Some universities and colleges introduced so-called "ghetto benches" where Jewish students were forced to sit and even began refusing Jews access to higher education and research. In the early thirties, Jews had constituted about 20 percent of the university students; in 1937 the number had dwindled to 7.5 percent. Catholic trade unions excluded Jews and so did the legal and medical societies. Before the German invasion in 1939, Jews had been virtually excluded from state services.

People´s changes of attitude can come about very fast. An example is Germany, where the National Socialist party grew from receiving 2.5 percent of the national votes in 1928 to 43.9 percent in 1933. It was no secret that the Nazi's highest priority was the "solution of the Jewish question" and that it was used recklessly during the party´s election campaigns. When the Nazis finally came to power, it went fast and relatively painless to make the majority of the German citizens ready to accept or even actively contribute to the disaster that eventually struck the Jews and other minorities.

Has the danger of extreme and deleterious politics subsided in Europe? Hardly - George Bernard Shaw noted that "we learn from history that we learn nothing from history." There is no doubts about the fact that the acts and ideas of careless politicians, who have based persons´ human value on something as vague as their race and national identity, have brought entire nations straight into the abyss of history's most comprehensive and best organized human slaughter. Yet, we continue to casually assess the value of individuals on the basis of their origin. Has such behavior ever brought about anything good? Prove to me if I´m wrong. I am sure of the fact that there is plenty of evidence that the opposite thinking – that all humans have a potential for benefitting and making others happy - is much more advantageous for all of us.

I conclude by recalling that populist nationalism is gaining ground in Europe and is jointly planning to destroy the European Community, something which, among others, Putin and his acolytes seem to appreciate. Here is the list of schemers:

Sweden Democrats who gained 12.9 percent in the 2014 election, the True Finns with 12.3 percent in 2014, the Norwegian Progress Party 16.3 percent in 2013, Danish People's Party 12.3 percent in 2011, the French National Front 13.6 percent in 2014, the Dutch Party for Freedom 15.4 percent in 2012, the Austrian Freedom Party 21.4 percent in 2013, the Hungarian Jobbik 20.5 percent in 2014, the UK Independence Party 27.5 percent in in the EU elections 2014, and the Belgian Vlaams Belang 3.7 percent in 2014.

Babel, Isaac (2002) The Complete Works of Isaac Babel. New York: Norton. Davies, Norman (2001) Heart of Europe: The Past in Poland's Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Davies, Norman (2003) White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919-20. London: Pimlico. Gerrits. André (2009) The Myth of Jewish Communism: A Historical Interpretation. Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang. Toppi, Sergio (2010) Sulle rotte dell´imaginario Vol. 3: Europee. Torino: Edizione San Paolo. Zambory-Moldován, Béla (2014) The Burning of the World: A memoir of 1914. New York: New York Review Books. Zamoyski, Adam (2014) Warsaw 1920 - Lenin's failed conquest of Europe. London: William Collins Books